by

Bill Weintraub

Preface

The Greeks believed that intense erotic bonds between warriors were crucial to the success of the hoplite formation.

They were right.

As we'll see, other Indo-European warrior peoples living in relatively close geographical proximity to the Greeks -- the Celts, the Teutons, and the Italic tribes -- practiced homoeroticism, and, like the Greeks, nudity in training and battle too.

But the Greeks institutionalized homosex to a degree that, so far as we know or, barring some spectacular new find, are likely to know, far outstripped their neighbors.

That's what's so striking about Greek Heroic Homosex -- the way key institutions in the culture were permeated by it and supported it: the arts, athletics, religious games, wrestling schools, communal messes, and, of course, war and the military.

Key to that support was the development of myths and stories about erotically bonded warriors and heroes.

On this page of Hoplites we're going to look closely at two of those couples -- Achilles and Patroclus, mythic heroes of the Trojan War, and Harmodius and Aristogeiton, real people whose heroic act of tyrannicide swiftly elevated them to mythic status.

And we'll also consider Alexander and Hephaestion, whose lives marked the culmination and whose deaths the beginning of the end of Greek Heroic Homosex.

Finally, we'll look at four funerary images, moving testament to the depth of the Warrior Bond.

by

Bill Weintraub

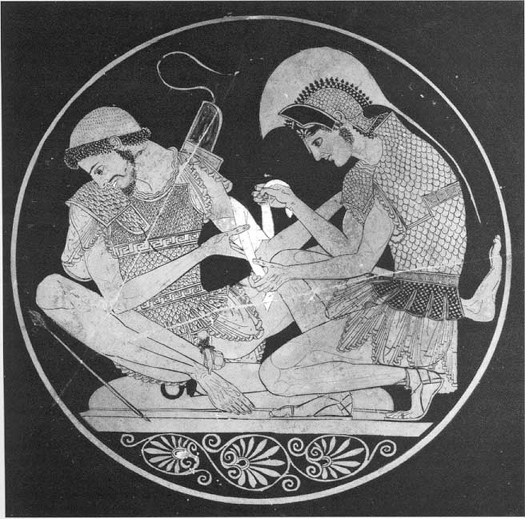

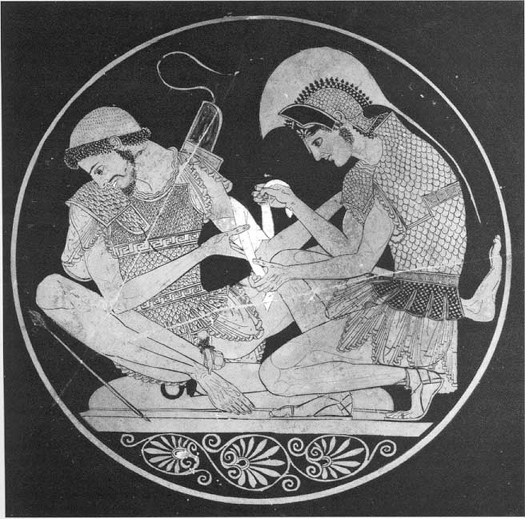

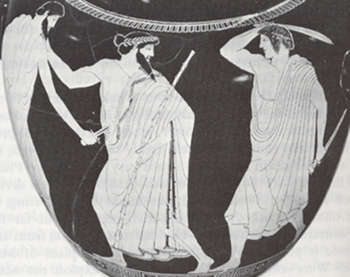

This stunning image of Achilles and Patroclus, heroes of the Trojan War, who were without question the most important role models for Greek warrior couples of the archaic, classical, and Hellenistic eras, is taken from a drinking cup or kylix of about 500 BCE.

In it, Achilles tenderly bandages the left arm of his lover Patroclus, who gently touches his shoulder for support, while gazing mournfully at the wounding arrow which pierced his shield.

They are the ideal warrior couple, like Gilgamesh and Enkidu, fighting side by side and devotedly solicitous of each other.

Without question the relationship between Achilles and Patroclus was the most important mythic model of the warrior bond for the men of archaic and classical Greece. Their boyhood together, their many shared battles, their tender devotion and their unwavering loyalty provided stirring stories and noble ideals for Greek youth and men. Equally inspiring was Achilles's fury when Patroclus was killed, his determination to avenge that death even if doing so meant his own, and the mixing of their ashes after death, one of the most intimate acts known to Greek culture.

The relationship thus modeled -- that of heroic friends -- was particularly appealing to ancient peoples, who lived in a world of dominating families and arranged marriages, and who had relatively little freedom of action in personal life.

Yet there was one sphere, they were told, in which they were free to act -- and that was in their choice of a friend, a fellow warrior, a lover, with whom they might imagine they'd be bonded, like Achilles and Patroclus, forever.

Further, only the bare outlines of the relationship were present in the Iliad. So playwrights like Aeschylus and philosophers like Plato and artists like the one who painted this cup were left to imagine what the details may have been.

As could any hoplite or Greek boy. And that was another part of the tremendous appeal of Achilles and Patroclus. Just enough was known that you could fill in much of either's biography with your own, easily imagine yourself in a hero's place, whether like Harmodius you were a citizen of a city-state in 520 BCE, or like Alexander, almost 200 years later, destined to be king.

So this one mythic model had an enormous impact upon men for literally hundreds of years, ascribing behavior to men who were erotically bonded that was noble, heroic, and uplifting.

Mythic Identification

When we consider the impact of this myth upon ancient men, and ask what effect it may have upon ourselves, we need to ponder whether, as Thomas Mann believed, "the Ego of antiquity was different from our own ... it received much from the past and by repeating it gave it presentness again. ... It was a mythical identification ... Life, or at any rate, significant life, was the reconstitution of the myth in flesh and blood; it referred to and appealed to the myth; only through it, through reference to the past, could it approve itself as genuine and significant."

Personally I don't agree with that part of Mann's observation which sets the ancients apart from ourselves, for in my own life myth is vital, and life without mythic referents feels empty.

And much of my life has been spent in the search for a hero, and in then living out heroic moments with him, as brutal as they sometimes were.

Indeed, I identify more with Achilles and Gilgamesh and Aristogeiton than I do with most of my contemporaries -- the behavior of these ancient, mythic heroes is instantly recognizable to me, their unwavering loyalty, their willingness to die for one another, and the extravagance of their grief when their beloved dies or is killed is unmistakeable to me, I recognize myself in them, and feel far closer to them than I do to the sickly denizens of mass gay culture.

So I don't agree with Mann that mythic identification was restricted to antiquity -- if I did, I wouldn't be writing Heroic Homosex.

But there's no question that Mann is right about the ancients, that to them "significant life was the reconstitution of the myth in flesh and blood" -- that, for example, when Alexander the Great and his lover Hephaestion ran naked round the putative tombs of Achilles and Patroclus at Troy, it wasn't, as some moderns think, a PR stunt. Not at all -- it was an expression of Alexander's mythic identification with Achilles, from whom he believed he was descended, and a tremendous, really breath-taking, heart-stopping affirmation of what he felt towards Hephaestion.

I too felt that when I wrestled and cock-humped with my lover Brett, or when we stood shoulder to shoulder at Jones Beach, sticks in hand, to face down a gang of fag-bashers, or when, walking through the East Village I slipped on some brass knuckles and he toughened his gait and armed himself with a set of keys protruding through his fist so we could walk safely and not too fast past another bunch of haters.

At such moments I remembered what Enkidu had said to Gilgamesh -- "Two people, companions, they can prevail!" -- and understood that it was true.

Just as I did when Brett and I battled -- as had Gilgamesh and Enkidu -- our ultimate enemy, a deadly disease, and I had to face, just as did Gilgamesh, the mortality of my hero.

So while I agree with Mann about the ancients, I also know that for me that reconstitution he speaks of is vital as well -- as I think it is for all people.

With that in mind -- remembering the power of myth for the ancients,

and what it might be for ourselves, if we permit it, if we allow ourselves to experience that mythic identification that is, as intended, both empowering and ennobling -- let's revisit this image.

First of all, look at the tenderness with which Achilles ministers to his lover, and look at how relaxed Patroclus is with him -- he's completely at home with this man, trusts him with his life.

See too that though the Greeks of the era believed that these heroes lived hundreds of years before, they wear the armor and display the nudity of the hoplite era -- another instance of mythic identification, of the sense that they might be we.

Notice the unusually naturalistic treatment of Patroclus' genitals, and how Achilles' genitals are also visible through the garment he wears beneath his cuirass. That's not because the cloth is transparent, which it would not have been, but because the Greeks thought it was extremely important not simply to be naked, but for the warrior's genitals to be in plain sight.

And so the artist has painted in the genitals, as though the cloth itself were diaphanous.

Around their chests and waists both Patroclus and Achilles have bands bearing the meander pattern. Though named for a river in Greece, that pattern greatly predates the Greeks, being first found in Paleolithic shrines to the Earth Goddess. The pattern is emblematic of the snake, immortal and phallic.

Notice too their slim, natural physiques -- these were not bodybuilders, but young men who spent their lives in warrior training.

Finally, note the stylistic resemblance between this painted drinking cup and Japanese woodcuts of the Edo period, two thousand years later. These cups and vase paintings were not known to the Japanese. Rather it would appear that these two warrior m2m cultures shared a parallel development -- and I have no doubt that if shown this kylix, a samurai would have understood it as clearly as do we.

If Achilles and Patroclus were the most potent mythic avatars of heroic homosex, Harmodius and Aristogeiton were its most famous real-life proponents, and their story, in which they and a tyrant died and the tyranny itself was destroyed so that the sanctity of their love could be preserved, swiftly seized the imagination of their peers, and turned them, almost overnight, into icons of democracy, freedom, and manly, noble love, which they remained for centuries.

Their story isn't complicated. In 514 BCE they lived in an Athens governed by a dictator, a tyrant as he was called.

Tyrants in ancient Greece were much like dictators in the modern world. They started off with a large measure of popular support, but then, through abuse of power, alienated their citizenry.

That's what happened with a family of Athenian tyrants named the Pisistradids. They began pretty well, but by the late 6th century, they 'd become corrupt.

The Athenians were ready for a change -- the Athenians were ready for democracy.

But the ruling brothers -- Hippias and Hipparchus -- wouldn't leave.

Instead they became more autocratic, more demanding of citizens in petty ways. Hipparchus, in particular, began hitting on Harmodius, the younger of an erotically-bonded warrior pair. Such lovers were supposed to be sexually and emotionally monogamous, and Harmodius, true to his vows, refused to have anything to do with Hipparchus.

Hipparchus, to get back at Harmodius, to punish him, begin insulting and slighting Harmodius' family, undertook a series of moves that steadily restricted their ability to function in civic life.

That part of the story is of course very interesting, for it tells us that the families of warrior lovers knew about and accepted the relationships. And, interestingly, there's no indication that the family pressured Harmodius to leave Aristogeiton or to satisfy Hipparchus. That would have been truly heinous, but the sort of thing that was routine in the great Eastern Empire of Persia.

But not in Greece.

As Hipparchus increased the pressure on Harmodius' family, the lovers considered their options. They didn't have many. They could go into exile, which might mean a degree of dishonor and which by no means would have stopped Hipparchus' punishment of Harmodius' family.

Or, they could get together with their friends and like-minded citizens, and put an end to the tyranny.

And that's what they plotted to do: on the day of an important religious procession, when it was common for men to be armed, Harmodius and Aristogeiton planned to strike.

But on that day, in advance of their plans, Hipparchus encountered Harmodius, and when Hipparchus insulted his sister by banning her from the procession, Harmodius, in a young man's rage, stabbed him to death on the spot. Harmodius was quickly cut down by Hipparchus' bodyguard, and Hippias, the surviving tyrant, had Aristogeiton tortured and killed.

But he couldn't make him talk, and many of the other conspirators managed to flee the city.

It took those others four more years, and the aid of a Spartan army, to get rid of Hippias, the surviving brother, but in 510 BCE Athens became a democracy.

Which it remained, vibrantly and gloriously, for about two hundred years.

And though their plot failed initially, the Athenians quite properly credited Harmodius' and Aristogeiton's act of tyrannicide as the crucial event in the eventual establishment of their democracy, and with it, a sea-change in the political life of Greece.

The honors heaped upon Harmodius and Aristogeiton in death are indicative of the high regard the Greeks had for warrior lovers who displayed this sort of heroism. Statues of these heroes were the first erected in the marketplace of Athens after the tyrant's overthrow; and an official called the Polemarch, a war leader who was responsible for sacrifices and funeral ceremonies for men killed in battle, had charge of a yearly festival honoring the slain tyrannicides and made sure that their descendants got preferential treatment at the civic-religious events that were so important in the life of the city-state.

And succeeding generations could not stop talking about them: every historian had a go at telling their story, including Herodotus, Thucydides, and Xenophon, while philosophers like Aristotle and Plato discussed the inner meaning of their act, and politicians like Aeschines sought to wrap themselves in the mantle of their glory.

The original statues were seized by the invading Persians in 480 BCE -- they well understood what an important symbol of freedom these two men were -- and carried off to Persepolis. One hundred and fifty years later, Alexander the Great conquered Persepolis and, before burning it to the ground, had the originals returned to the Athenians, a gesture of respect to democratic citizens with whom he often didn't get along.

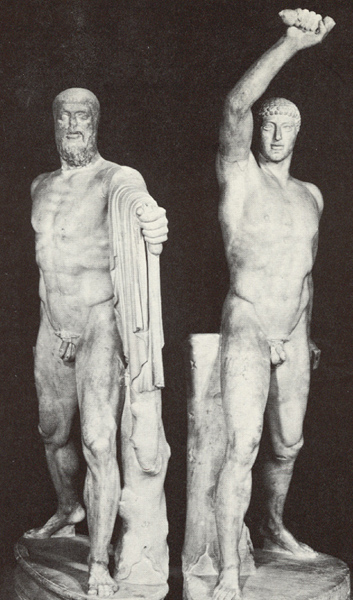

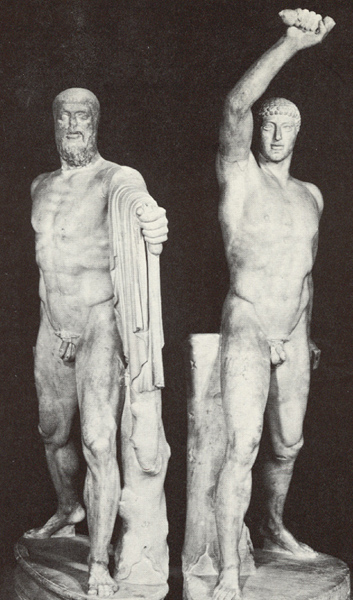

In the meantime, though, the Athenians had replaced the looted statues, and I suspect that the image here -- a Roman copy made in about 200 AD and now in a Naples museum -- is a copy of that replacement group.

And what was this copy doing in an imperial Roman city? It's simple:

The Romans, who considered themselves republicans long after they had an empire, also admired Harmodius and Aristogeiton, seeing in them models both of manly love and love of one's country, exemplars of the Roman motto, "Dulce et Decorum Est Pro Patria Mori" -- it is sweet and honorable to die for one's country.

So once again let's revisit an image:

We don't know exactly how long after their deaths the originals of these statues were erected, and though it appears to have been well within living memory of those who had known them, the images may be idealized. Nevertheless, what we see when we view these statues is what we would expect: two vigorous young men, of perhaps twenty and twenty-five, one's face bearded in classic "erastes" fashion, the other's smooth, their nude bodies hard, muscular, and athletic. Standing side by side, they look out at the observer with confident resolve: Aristogeiton holds his sword before him, while Harmodius brandishes his in the air over his head in a youthful gesture of anticipated victory. There is an aura of eternity about the pair, and why not? When these Roman copies were made the lovers had been dead for seven hundred years, but they, and their passionate commitment to die for each other and for freedom, were still remembered.

Did mythic identification play a role in their act? Of course it did. In choosing liberty or death, rather than exile, they were simply doing what Achilles and Patroclus had done -- promising to live and die for each other, and keeping that promise.

So in many ways, Harmodius and Aristogeiton set the standard for warrior lovers first for the Athenians, and then the rest of the Greeks (the Spartans had their own version of the Harmodius and Aristogeiton story, in which Hyacinth, a Spartan prince, stays true to his lover Apollo and is killed by Boreas, the north wind), and finally the Roman world. Slightly apart in age, masculine, athletic, loyal, exemplars of military valor, devoted and willing to die for each other, they were what male lovers were supposed to be. Later generations of Christian homophobes tried to erase their memory, but their story was ubiquitous in the ancient world, and so it has survived.

Two last points:

Firstly, ancient authors are quite clear that what happened among Harmodius, Aristogeiton, and Hipparchus was due to a love affair. Thucydides for example says that "Harmodius was then in the flower of youthful beauty, and Aristogeiton, a citizen of the middle rank, was his lover."

What did that mean sexually? As I'll discuss at some length later in Heroic Homosex -- The Greeks, it was supposed to mean frot -- not anal. While it's clear that what Hipparchus wanted -- because we see it in other tyrants -- was anal sex. And indeed Thucydides says that Aristogeiton feared that "the powerful Hipparchus might take Harmodius by force."

I don't think he means force him to have frottage -- just isn't likely.

In that sense, when we look at Harmodius and Aristogeiton, we see two men fighting not just a political tyranny, but an attempt to impose a sexual one as well.

And that's something with which we can all identify.

Secondly, when you look at their image, I ask you to try to imagine a contemporary American equivalent:

Imagine for example that Tom Paine and Patrick Henry were lovers who killed the English governor of Virginia because he tried to come between them, that their act touched off the American revolution, and that since Yorktown nude statues of them have been placed in every courthouse square, and that no congressional speech is complete without a reference to these heroic patriots and lovers.

And then imagine a boyhood and adolescence shaped by those role models, rather than Liberace or Boy George.

There's a difference.

But Harmodius and Aristogeiton were just as real, and historically a lot more significant.

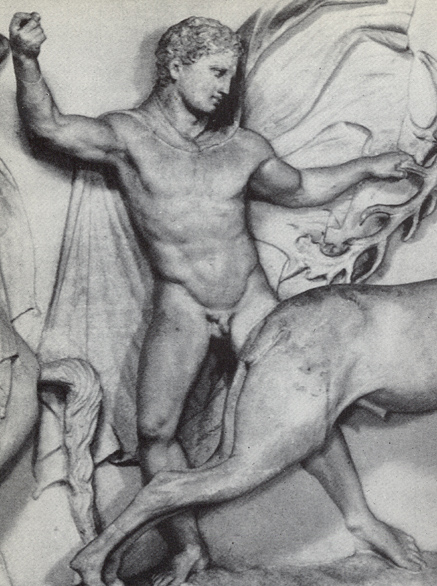

This is an image of Alexander and Hephaestion riding into battle, an image from the so-called Alexander Sarcophagus in the ancient city of Sidon.

Alexander's on the far left, Hephaestion's on the far right.

I've placed them here because in a sense the lives of Alexander and Hephaestion mark the culmination of the ethos of Greek Heroic Homosex, while their deaths mark its end.

Certainly no one had a greater mythic identification with Achilles than did Alexander...

...and his love for Hephaestion, his very own Patroclus, was without limit.

Like Achilles and Patroclus, they'd grown up together, even had their own Chiron in the philosopher Aristotle, who got the job of tutoring these boys long before he was famous simply because he was the nephew of their father's physician.

(There was a well-known correspondence between Hephaestion and Aristotle among Aristotle's Collected Works -- unfortunately it's been lost, but apparently Hephaestion, as well as being a brilliant officer and soldier, could more than hold his own with Plato's successor.)

Of course Alexander and Hephaestion, like Achilles and Patroclus, had been lovers since youth.

And, as had Jason with the Argonauts, they'd gathered a group of brilliant young heroes around them, men like Craterus and Ptolemy, Macedonia's best and brightest, who helped them change the world.

Plus the personal bravery of these two men is almost beyond belief.

They were both wounded repeatedly -- Alexander insisted on leading his troops into battle and then staying in the vanguard, and so received many wounds, often serious.

And they made no secret of their love. When the Persian Queen Mother mistakenly addressed Hephaestion as Alexander, and then trembled at her mistake, Alexander replied, "Never mind, for he too is Alexander."

You can't ask for more than that.

And of course Alexander's grief at Hephaestion's death would be legendary, except that we have eye-witness accounts of it: of how he lay atop the corpse for more than a day, and had to be pulled off of it by his officers, and of how he was sick with grief for months.

And too how he planned massive memorials for Hephaestion throughout his newly-won empire, plans that were never carried out simply because Alexander himself died so soon after his lover.

Indeed Alexander's mythic identification with Achilles was so great, that one has to wonder what would have happened if Hephaestion had not existed to fulfill the role of Patroclus.

Maybe the conquests would never have occurred.

After Alexander's death, after all, his surviving generals didn't carry on his work. They lacked his passionate conviction, his belief in destiny. Instead they simply carved up the empire and spent the rest of their lives guarding the bloody spoils.

Now of course homosex continued as an ideal and a reality beyond the deaths of Alexander and Hephaestion -- heroic notions of homosex are found in Hellenistic and Roman novels, in philosophic treatises, and in poetry for at least 800 years more.

For example, writing more than 300 years after Alexander's death in Babylon, Virgil speaks of Nisus and Euryalus, heroic warrior lovers who die for each other and whose fame will last he says as long as Rome itself.

But, as I'll argue elsewhere, the political conditions that created Greek Heroic Homosex died with Alexander. In the radically different world which emerged after his conquests, citizen warriors were replaced by professional soldiers, while the Greek city-states themselves were supplanted first by Hellenistic kingdoms, and then by the empire of Rome.

In such a world, erotic bonds between warriors were far less important. As was ritual in warfare. The Celts for example, whom the Romans called "Gauls," continued to practice nudity in battle -- and the Romans destroyed them.

So looked at historically, there's a sense in which these three couples -- Achilles and Patroclus, Harmodius and Aristogeiton, and Alexander and Hephaestion -- mark the mythic beginning, the historical apogee, and the political end of Heroic Homosex.

Note by the way that all six of these warriors traded length of days for glory, and that none long survived his partner.

I'll have more to say about Alexander and Hephaestion -- one of the most beautiful couples in all of history -- later in the series.

A Warrior Mourns

In this touching scene, a warrior mourns for a fallen comrade or lover -- most likely the latter -- by cutting off a lock of his elaborately dressed hair.

This gesture of grief and remembrance is at least as old as the Iliad.

The warrior stands before a makeshift shrine consisting of his beloved's helmet and shield propped up against a folding chair, the sort taken on campaign.

And we can see his own shield and spear in the background -- clearly he will soon return to battle, perhaps to avenge this loss.

Like the tender care Achilles gives Patroclus in the first illustration on this page, this painting is yet another reminder of the deep bonds between warriors.

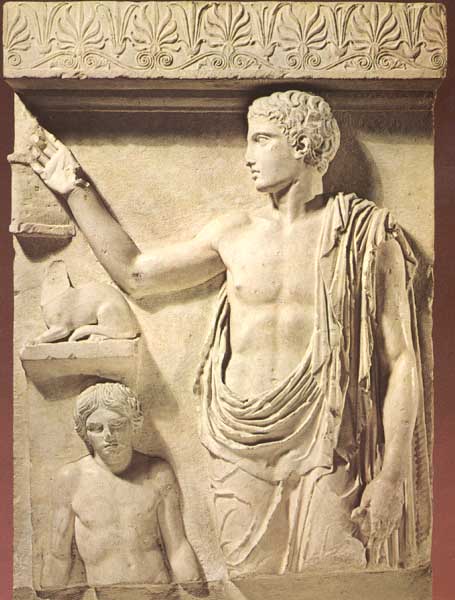

Cat Stele

In this famous funerary stele or grave marker, a handsome young warrior, his himation open to expose his beautiful chest, looks into the unknown, while at his feet a youth -- almost certainly his lover -- stares out at us with an expression of ineffable grief.

There is about the scene a stillness and otherworldly calm that makes it unforgettable.

A masterwork of classical Greece, inspired by a warrior ethos.

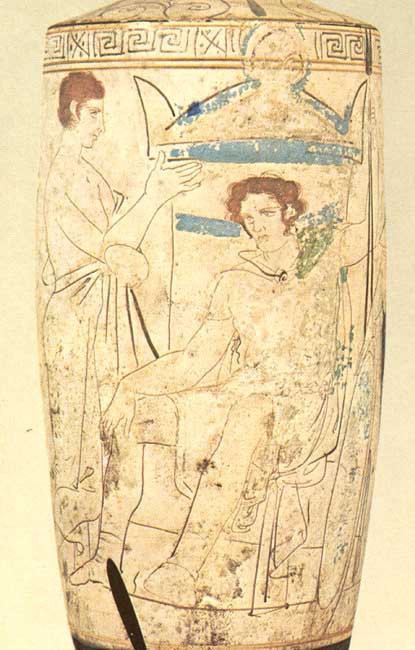

Lekythos

On this lekythos or funerary jar, a warrior slumps wearily, regarded mournfully by his disconsolate lover.

Another compelling image of loss and remembrance.

Hoplites

The stele of Chairedemos and Lyceas, warrior lovers who fell together in the Peloponnesian War, and were buried together.

True successors to Achilles and Patroclus and Harmodius and Aristogeiton.

And true proponents of Heroic Homosex.

© All material on this site Copyright 2001 - 2011 by Bill Weintraub. All rights reserved.

there are different versions of the actual event -- in this one, the lovers act together

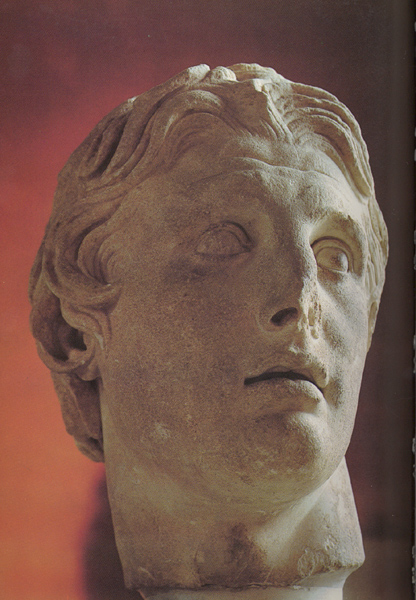

the only known portrait

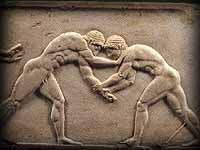

Nude Combat

| Heroes Site Guide | Toward a New Concept of M2M | What Sex Is | In Search of an Heroic Friend | Masculinity and Spirit |

| Jocks and Cocks | Gilgamesh | The Greeks | Hoplites! | The Warrior Bond | Nude Combat | Phallic, Masculine, Heroic | Reading |

| Heroic Homosex Home | Cockrub Warriors Home | Heroes Home | Story of Bill and Brett Home | Frot Club Home |

| Definitions | FAQs | Join Us | Contact Us | Tell Your Story |