by

Bill Weintraub

by

Bill Weintraub

Preface

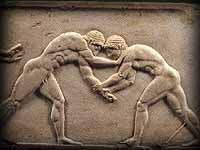

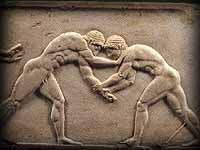

There are literally thousands of images -- painted on walls, vases, jars, and drinking cups, adorning the sculpted pediments of temples and standing free in marble and bronze, hammered into armor, and even painstakingly worked into mosaics -- of Greek men playing, working, training, hunting, but, most of all, fighting, nude.

For years scholars assumed that this nudity in combat was just an artistic convention. For after all, who could go possibly go into perilous and public battle with his genitals exposed, these "private parts" that we moderns hide ashamedly, to be seen only by wives, lovers, and doctors?

But recently scholars have begun to reconsider. Students of the ancient world have long known accounts by Greek and Roman historians of Celtic nudity in battle, as well as naked war dances among the Teutons and Italic peoples. More recently, anthropologists have begun to understand how closely the Greeks were related to these other Indo-European peoples, and they've come to acknowledge that warrior pederasty, far from being unusual, was probably more often the norm among such tribes, and that it's likely therefore that Greek homosex was not an isolated phenomenon.

Once scholars had admitted that aspects of Greek homosex might be best understood by reference to practices among more "primitive" warrior cultures, they could also begin to look at the ritual aspect of Greek warfare, and how much closer it was to primitive practices of war than modern, and in so doing begin to admit that nude combat may well have been common.

Indeed, today illustrated military histories like the Osprey Series, hardly written for a "gay" audience, routinely show Greek and Celtic warriors nude.

So, the questions must be asked, what did it mean to these men to go into battle nude, to display their genitals so openly to both their friends and enemies? And what relationship did that nudity in war have to two other spheres of m2m warrior life which involved both nudity and strenuous physical contact with another man -- one, the very public act of wrestling, and the other, the very private act of sex?

In this section of Heroic Homosex -- The Greeks we'll begin to explore those issues, and consider in particular the role of what I've called natural male sex aggression in Greek life. And though I don't think there are any easy answers, I do think that as men into fightin and frot we may be able to look at these images with a degree of empathy others cannot, and, using what Harry Haye has called the third eye of intuition, start to understand the significance and power of nude combat to these warriors of Heroic Homosex.

by

Bill Weintraub

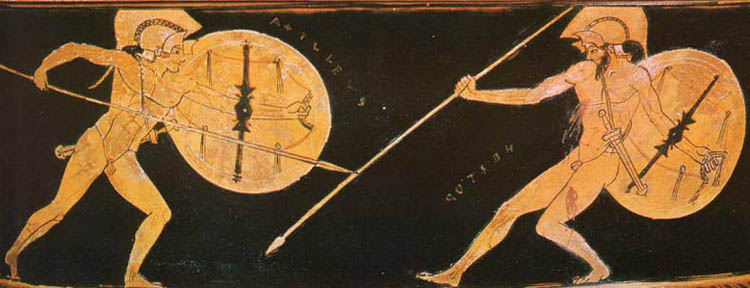

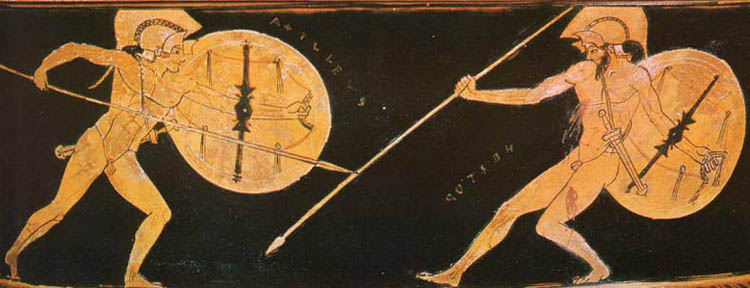

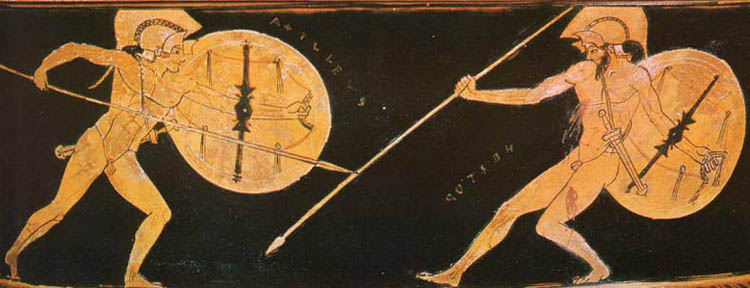

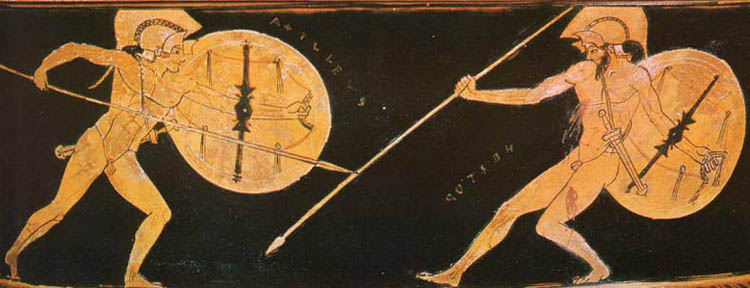

Following Patroclus' death in man-to-man combat with Hector, the enraged Achilles killed Hector in turn.

Achilles vengeful pursuit of Hector and Hector's dogged struggle to survive present some of the most potent images of love, rage, and nobility in all of Greek literature and myth.

And so this is an exceptionally powerful image, made more so for both us and the Greeks by the nudity of the two heroes.

In looking at this painting, we need to remember how important nudity in competition was to the Greeks, and how intense this particular competition and moment was.

Two principles and ways of life collided here.

Hector was fighting not just for his life, but for his city and his family, for the beauties and comforts of domesticity.

Achilles, who'd come to Troy as a marauder, to loot, burn, and destroy, no longer cared about his own life. His only thought was to avenge his dead lover, to kill the man who'd killed his beloved Patroclus and then dishonor his corpse.

So the artist has captured that exact moment, when, after years of conflict and brutal war, the fight between the Greeks and the Trojans has come down to this single nude combat between their greatest heroes, and Achilles, his spear poised to push the already wounded Hector's aside, is about to deliver the final fatal blow.

After which he'll tie the naked body of his vanquished foe to his chariot and desecrate it by dragging it through the dust of the blood-stained plain outside Troy.

What's more, it's clear that the nudity in this painting is neither accidental nor incidental.

For, if you trace an imaginary line from Achilles' eyes, you will see that at this culminating moment, he's staring at Hector's genitals.

As Hector is at his.

So at this pivotal point in the Trojan War, the artist has imagined a combat that in its essence is sexual.

And that is part of the power of Greek Heroic Homosex -- eroticism suffuses its every m2m moment.

Something that men into fightin and frot understand in the very depths of their being.

The Prevalence and Significance of Nude Combat

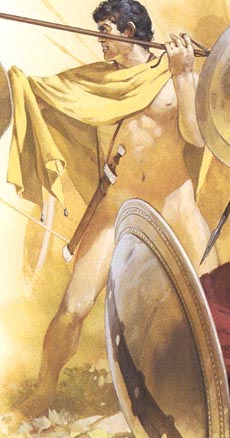

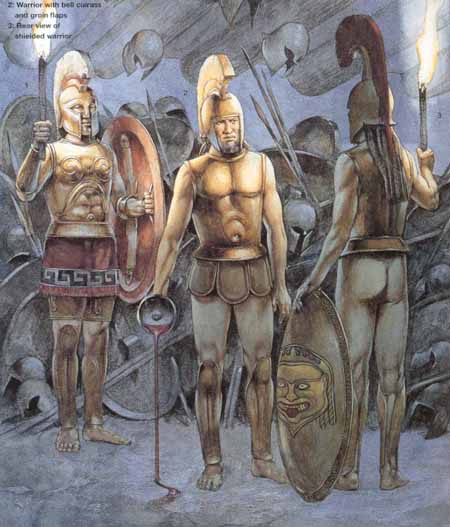

As in the painting of Achilles and Patroclus in The Warrior Bond, both men carry the basic panoply or equipment of the Greek hoplite: a helmet, often with a horsehair crest; a shield, made of leather and wood covered with a thin layer of bronze and always held in the left hand; a spear; a sword; and greaves, or lower leg protectors.

In addition to this basic panoply, hoplites sometimes wore a breastplate, sometimes made of metal, and sometimes of leather that flared slightly at the waist, and so known to military historians as a bell-shaped cuirass. Sometimes, though not always, the breastplate or cuirass might have leather groin flaps as well.

Over the 327-year period from the introduction of the hoplite formation to the death of Alexander the Great (650 to 323 BCE), the breastplate and cuirass went in and out of military fashion, depending upon the tactical needs of the day. If, for example, maneuverability and speed were paramount, or if the battle was at sea, the cuirass or breastplate was discarded.

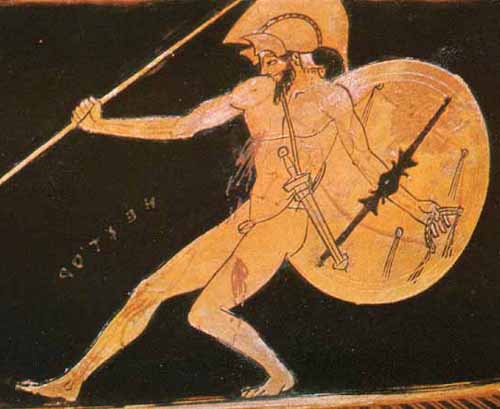

What's striking though is that even when wearing a muscle cuirass or breastplate, hoplites often left their genitals exposed. We have many images, like that of this Lakonian warrior, of men wearing a helmet, greaves, and cuirass -- but nothing else. So one could protect one's chest and still enter combat with genitals visible to the enemy.

In part, that was possible because of the size of the shield. It was big enough that it could readily cover the genitals when necessary.

Further, for many years, there was nothing among the Greeks resembling a uniform. Hoplites were responsible for providing their own armament -- and though of course every hoplite had to have a shield and spear of uniform size, other equipment might vary widely. For example, it wasn't until relatively late in the Peloponessian war that commanders realized that unless every shield was emblazoned with the same device, there was a risk in melees of countrymen killing countrymen.

We can see this variability clearly in this artist's reconstruction of a Spartan temple ca. 530 BCE.

Each man's cuirass is slightly different, the helmets are different, one man has groin flaps, while another, based on the small bronze just above, is nude.

But genital nudity is very common, far more the rule than is genital covering.

And of course, as I said in the preface, this nudity in combat was not limited to the Greeks, but was found throughout other Indo-European peoples as well.

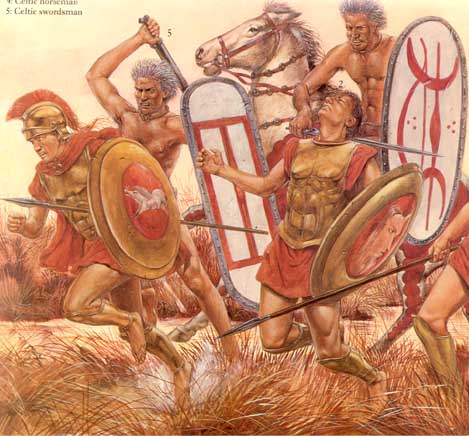

That nudity is best documented among the Celts, whom the Romans called "Gauls." During the Hellenistic era and the early Roman republic, the Celts invaded both the Greek and Italian peninsulas and even sacked the city of Rome itself.

As a result we have both written accounts and sculpted and painted images of these warriors, which are quite consistent.

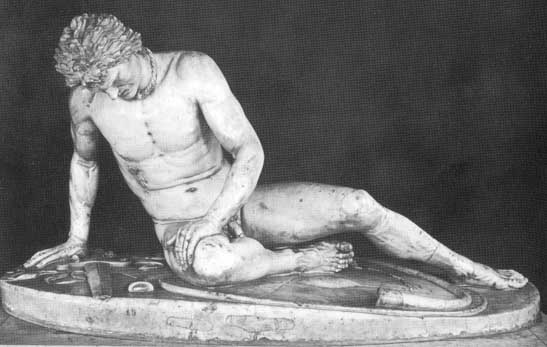

The most famous sculpted image is the so-called Dying Gaul, a Roman copy of a lost Greek original.

The sculpted presentation of this handsome but defeated warrior matches the descriptions in the Greek histories.

And so we know it was common for these tall, fair-haired warriors to have a moustache and wear a gold torque, like the caduceus an image of the double snake, around their necks. In addition, they frequently put lime or some other substance in their hair to give it a spiked effect.

The combination of height, nudity, spiked hair, and fearless, often berserk behavior in battle, made them both frightening and dangerous, and both the Greeks and the Romans had a hard time fighting them off, as we can see in this artist's depiction of a Roman defeat in the 4th century BCE.

So I think it's safe to say, given the cross-cultural evidence and the abundant evidence from the Greeks themselves, that the Greeks often fought nude, because that nudity was intrinsic to their culture, and vital to their sense of themselves in competition with other men.

Just as it is for men into fightin and frot.

When we look at the Greeks, then, we can begin to recognize the relationship between the male sex aggression that's so natural to ourselves, and its expression by one of the world's great warrior cultures.

Now of course it's difficult for us today, raised to "modestly" conceal our "private parts," to fully understand a culture in which there was no genital shame, and in which male nudity before other males was not simply accepted but required. But to the Greeks, nudity, like homosex, was key to the civilized and free man, and their interest in it was intense.

That's why in so many of the vase paintings, such as that of Achilles and Patroclus in The Warrior Bond, or the handsome hoplite below, or the hoplite (actually a giant) fleeing the gods at left, the genitals are visible even when they need not be, when clothing or body position might naturally have obscured them.

This focus upon the male genitals is an expression of Greek homosex -- it's not merely aesthetic, it's erotic.

Notice too, that, as we'd expect in a sexual society structured around frot, attention is directed to the genitals, not the buttocks. As we'll see when we look at explicitly erotic vase paintings, when men or youths are courting, they touch their partners' genitals.

For the Greeks, then, contact with other men was frequently eroticized, and that eroticism extended to warfare too.

That doesn't mean that the Greeks necessarily went into battle with erections, though some may have.

War was still war: terrifying, brutal, savage, and deadly.

Yet the world of the Greek male was suffused with m2m eros. And when looking at the vase paintings and other works of art, we can see that war, both in anticipation and remembrance, was at times yet another expression of a fierce erotic impulse.

The Hoplite as Object of Desire

In this painting from a kylix or drinking cup, the focus is clearly on the young warrior's beauty.

Once again he's equipped with the basic hoplite panoply of helmet, spear, shield, and greaves. (The cloth around his waist is decorative -- it had no function, and would not have been used as a loincloth.)

Notice again the prominence of the genitals, which could easily have been obscured, and that the penis is relaxed, with the foreskin completely covering the glans.

Only the spear gives a hint of the warrior's erotic power.

There are literally thousands of images like these among the vase paintings -- handsome young men presented to be admired for their youth , strength, and courage, their incorporation of the warrior virtues.

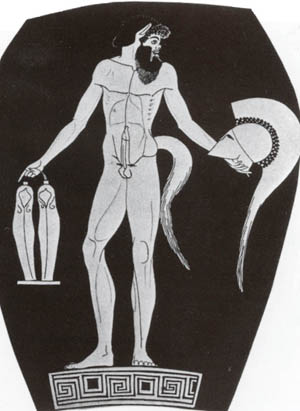

Sex and War -- A Satyr Equips a Hoplite

In this ambiguous image, a fully-erect satyr hands a hoplite his helmet and greaves.

Satyrs were mythical creatures who belong to the oldest stratum of Greek religion, that of the Earth Mother and her consorts, which was replaced but not entirely superceded by the worship of the Olympian gods.

For unlike the Semites, who ruthlessly suppressed any remnants of the Earth Mother cults in the areas they conquered, it was part of the genius of the Greeks to incorporate parts of the religion of the vanquished indigenous peoples of the Balkans, Crete, and Ionia into their own mythology.

As though to emphasize his link to those old religions, this satyr stands upon a pedestal decorated with a labyrinth, symbol of the feminine priniciple.

Satyrs are slaves of desire, unable to control their sexual yearnings, and frequently shown erect.

Is this one erect because he's in the presence of a handsome hoplite? Probably. But there's also a suggestion here of a transfer of erotic power, of an erotic energy that the warrior could call on to see him through the battle.

Typically, before going into combat, hoplites prayed not to Ares, the god of war, but to his son Eros, the god of m2m love. They sought a strengthening of the erotic bonds that would hold the hoplite formation tight and strong, and give them the power to prevail.

Nude athletics and nude drill prepare the warrior for nude combat. AND

this Osprey artist's reconstruction is based upon a vase painting

Nude Combat 2!

© All material on this site Copyright 2001 - 2011 by Bill Weintraub. All rights reserved.