a sublime, beautiful act

a sublime, beautiful act

2-13-2007

This is an article from the International Herald Tribune about ritualized fighting among indigenous peoples in the Andes.

The title is misleading.

Please take a look.

Ritual fades into blur of drinking and fighting

By Simon Romero

Published: February 12, 2007

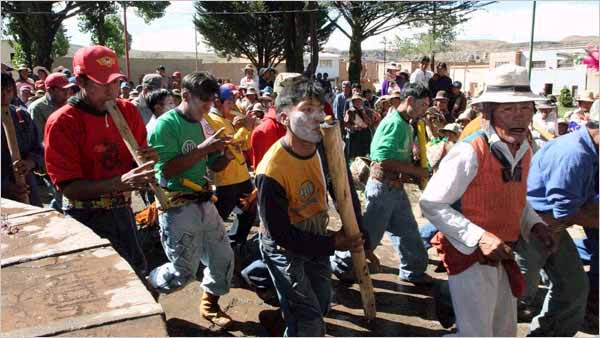

SACACA, Bolivia : For hundreds of years, the Indians of Bolivia's high plains have trekked to this town in early February. They dance, drink chicha, the fermented beverage made here from rye, and then fight one another until blood stains the dirt alleyways.

The ritual, called Tinku, a word that means "encounter" in both Aymara and Quechua, was once widespread throughout the Andean world, predating the arrival of the conquistadors. Anthropologists say it now tenuously exists just in this isolated pocket of Bolivia, seven hours southeast of La Paz by bus on a washboard dirt road.

To the chagrin of Roman Catholic priests who would like to see Tinku fade into the past, political officials here want it to survive.

"Tinku is a sublime, beautiful act," said Wilson Araoz, the mayor of Sacaca and a leading official in the Popular Indigenous Movement, a party that is part of the coalition supporting Evo Morales, Bolivia's first indigenous president.

Emboldened by Morales's efforts to strengthen Bolivia's indigenous cultures, Araoz's party is one of several political organizations pushing to preserve endangered traditions like Tinku.

"There's a predisposition in all of us to do Tinku," Araoz said in an interview. "I believe that denying that impulse is harmful."

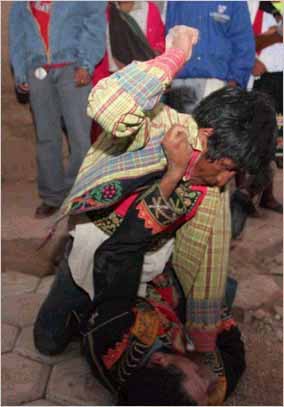

No one disputes that Tinku can be harmful, at least physically. The fighting, though ritualized through music and dance, is far from organized, less like boxing and more like street brawling.

Not everyone takes part. Men of roughly equal size and age square off against each other on the streets surrounding the plaza, though sometimes women also enter the fray. Some of the men wear leather helmets and gloves and carry woven coca-wallets. But the fighting can also be bare knuckle.

In one fight at a dirt intersection, two men in their 50s punched and kicked each other for about 10 minutes, their faces bloodied as a crowd cheered them on. By the time exhaustion overwhelmed them, both were still conscious, though in a trancelike state.

Bystanders sometimes step in to break up contests that become too lopsided. In addition to bruised faces and limbs, deaths sometimes occur.

No one died at this year's Tinku here, but blood certainly flowed. Some of the fighting evolved into generalized rock-throwing brawls with screams of aggression in Quechua and Aymara.

Some of the Tinku fighters could be found passed out on the ground, though it was not clear whether concussions or chicha were to blame.

"It was a good year, but slower than before," said José Acuña Gabriel, 22, a Quechua-speaking Indian who wore a colorful ceremonial vest over a secondhand Operation Desert Storm T-shirt.

Expressing concern with Tinku's violence, priests in this region, North Potosí, have been trying to eliminate the ritual fighting. Some priests have told indigenous leaders that church aid and community religious services could be withheld if residents took part in Tinku.

"There are profound things within these people that I still don't understand," said Carlos Ortigosa, a Spanish priest who has lived in Sacaca for the last 10 years. "But basically Tinku is an event in which people kick each other when they're down and die with some frequency. It's not agreeable to see people treating each other so badly."

Anthropologists say Tinku represents much more than fighting. But the fighting, often between members of different communities, can be a way to confirm or defend collective landholdings, or to bring good fortune at harvest time.

It is also a chance for young men to show off in front of women from other communities. Couples often meet at Tinkus and marriages are known to result.

Tristan Platt, director of the Center for Amerindian Studies at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, said Tinku's origins were hard to pin down though indigenous communities might have practiced something similar as far back as 1100. The periodic channeling of communal violence may serve to reduce conflict during the rest of the year, he said.

Rare acts of cannibalism have occurred, Platt said, and are thought by participants to be legitimized by the Catholic eucharist, letting them believe they are eating the flesh of a divinized human being.

Ramiro Molina, an anthropologist and director of the Museum of Ethnography and Folklore in La Paz, said blood was required for Tinku's participants to feel they had consummated a harvest fertility rite.

"The West isn't used to seeing such violence out in the open, ritualized and organized in such a way," Molina said. "So of course this seems shocking at first glance."

Most of the several hundred people who attended were subsistence farmers who walked to Sacaca and bartered in the town plaza for corn, blankets, shoes, chicha and coca leaf before the dancing began. Those who took part said the fighting was as natural as farming potatoes.

"I do it because it's fun," said Esteban Lisidro Aguilario, 20, between turns playing the Tinku dance's haunting rhythm on his pinquillo, a flute made for the occasion.

Sacaca, even with its isolation, feels the tug of the outside world in ways that are diluting the appeal of rituals like Tinku. Entel, the national phone company, opened a booth here five months ago with three Internet-connected computers. Many of the town's children and teenagers seemed more entranced by the instant messaging and games on those machines than with the centuries-old ritual unfolding around them.

This year's Tinku drew only about half the number that had come three years ago.

Bolivia's largest Tinku is not in Sacaca but in Macha, another town in North Potosí, where thousands gather to fight each May. The police there sometimes disperse brawls with tear gas. Officials in Macha have started charging admission to foreign tourists.

Sacaca's leaders hope their ritual may become an attraction as well, though for now outsiders are still oddities. The only lodging here is a room in a shopkeeper's house on the plaza for $3 a night.

"Tinku is like a psychologist that helps us overcome our traumas," said Osvaldo Echeverría, a Sacaca cultural official. "We have a lot to learn about the world, but the world also has a lot learn from us."

Bill Weintraub:

What you can see here is a remnant of pre-colonial indigenous life.

Called Tinku.

It's about MEN and it's about FIGHTING.

The Catholic priests of course are opposed to it.

The anthropologists aren't sure what to make of it.

And the Tribune reporter is confused by it.

But the local indigenous leader calls it "a sublime, beautiful act."

We should be clear that it's voluntary.

That in some ways it resembles the group wrestling battles among Sioux children described by Charles Eastman.

That there's a Tinku dance associated with it, which is played on a special flute.

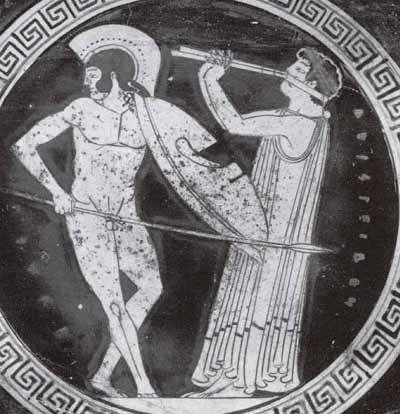

And that the Greeks had a ritual they called the Pyrrhic Dance, which was a series of ritualized fighting movements, also accompanied by the flute.

Clearly, Tinku speaks to the need of Men to fight.

One priest says, ""There are profound things within these people that I still don't understand."

And then condemns the violence.

An indigenous leader responds:

"Tinku is like a psychologist that helps us overcome our traumas," said Osvaldo Echeverría, a Sacaca cultural official. "We have a lot to learn about the world, but the world also has a lot learn from us."

Yes.

Suppose the priests were successful in eliminating Tinku?

Would alcoholism increase?

Drug use?

Domestic violence?

Murder?

The culture is a whole.

If you take something of value from it -- and have nothing to put in its place -- there will be problems.

In the slide show which accompanied the article, another indigenous leader says,

"There's a predisposition in all of us to do Tinku," Araoz said in an interview. "I believe that denying that impulse is harmful."

He's right.

This is from an email from Frances -- she's commenting on The Comradeship of Wounds:

It seems like American Indians kind of hold a key to helping us understand warriordom, and what has happened to us. Think of what was torn away from them; no wonder there were/are such high rates of alcoholism/suicide. We've had how many centuries to lose what they lost within several decades? I think it was Chief Gall who refused to be in Buffalo Bill's dog and pony show, and a lot of the photos that were taken were of that nature.

That was interesting about what Franklin had to say about the Greek statuary. The Americans were looking towards the ancient world of the Greeks for inspiration, while at the same time, usually, destroying peoples that often lived closer to some of those classical ideals themselves.

That's correct.

Let's look at some pix:

You can see the resemblance to UFC.

In the UFC, this is called ground and pound.

And here we have a vase painting of the Pyrrhic Dance.

One Warrior plays the flute while the other does his martial dance.

Here Indians play the flute while their tribal brothers fight.

This is why C. G. Jung believed there exists a collective unconscious.

This is not a mystical concept.

Jung believed that this universal unconscious resided physically in our bodies -- today we would say, in our genes.

Jung's student Joseph Campbell didn't agree -- he thought that cultural diffusion could account for these striking similarities.

But -- what's the chance that ancient Greeks made it to the Andes?

I know for myself that elements of my own biography don't make much sense unless there is indeed a collective unconscious.

So I think that's true.

I think there exists within Men a Warrior impulse and a Warrior archetype -- a model.

Which yearns to be fulfilled.

And which finds expression in certain predictable ways.

Including fighting.

In The Comradeship of Wounds I have this picture of two UFC fighters after their fight.

Of which Frances said to me:

I loved the photos of the UFC fighters Forrest Griffin and Stephen Bonnar. They look more alive after the fight than they did before it, and they have the sweet look of little boys with one arm over the others' shoulder that one sees so rarely among men. They look healthy and whole.

"more alive after the fight"

"healthy and whole"

That's why Men fight.

Because when they're fighting they feel alive.

And because it makes them healthy and whole.

Men need to fight.

Men need the company of other Men.

Men need the freedom to be sexual with other Men.

Deprive them of those things -- and there are massive problems.

These Andean Indians -- of course it's cold in the Andes -- fight clothed.

Do Men need to fight nude?

I don't know.

I suspect they do.

And perhaps before the Europeans came these Indians did.

You have to wonder though how many of these fighting rituals have been lost.

And at what cost to Men and to all humankind.

Robert Loring:

Imagine a world in which the Warrior Ethos was something that was honored and esteemed instead of shunned and discouraged. A world in which natural male aggression was respected and valued. Natural male aggression would be self disciplined by such males as they walked through their lives living as honorable and noble Warriors.

The naturally masculine male would have a major place in such a world just as he did in ancient days when the Hoplites and others ruled the times. No longer would there be a war against the natural male, natural masculinity, or natural male aggression. Man would truly be once again MASCULINE MAN. Males would be unafraid to love their brothers in the natural bonds of the brotherhood of man. Males could simply be themselves.

The world we live in today stands against this vision at every turn. It opposes anything that even comes near natural maleness, natural masculinity, and natural male aggression be that aggression disciplined aggression or unbridled aggressiveness. Today's society is a society of hypocrisy! More and more the nude male body is becoming an object of shame and disgust even though the nude male body is something beautiful, masculine, serene, and sacred.

There is a war against the natural male and the sad fact is that most males are losing that war. To even begin to win that war, males need to return to what they once were and be unafraid again to love, to be simply themselves, and to being noble modern Warriors!

Bill Weintraub

© All material Copyright 2007 by Bill Weintraub. All rights reserved.

Add a reply to this discussion

Back to Personal Stories

AND

Warriors Speak is presented by The Man2Man Alliance, an organization of men into Frot

To learn more about Frot, ck out What's Hot About Frot

Or visit our FAQs page.

| Heroes Site Guide | Toward a New Concept of M2M | What Sex Is |In Search of an Heroic Friend | Masculinity and Spirit |

| Jocks and Cocks | Gilgamesh | The Greeks | Hoplites! | The Warrior Bond | Nude Combat | Phallic, Masculine, Heroic | Reading |

| Heroic Homosex Home | Cockrub Warriors Home | Heroes Home | Story of Bill and Brett Home | Frot Club Home |

| Definitions | FAQs | Join Us | Contact Us | Tell Your Story |

© All material on this site Copyright 2001 - 2010 by Bill Weintraub. All rights reserved.