The Comradeship of Wounds

2-4-2007

Your present rage perhaps

Foretokens future love, a memory

To warm your hearts.'Nor were the old man's words

A vain presage. This comradeship of wounds

Issued in such fine trust as Theseus had

Who shared high risks with fierce Pirithous,

Or Pylades who, when Orestes' mind

Was gone, preserved him from the Fury's rage.So then the turmoil in their hearts was soothed

By the king's words...-- Publius Papinius Statius, died 96 AD. The Thebaid.

Friendship is held to be the severest test of character. It is easy, we think, to be loyal to family and clan, whose blood is in our own veins. Love between man and woman is founded on the mating instinct and is not free from desire and self-seeking. But to have a friend, and to be true under any and all trials, is the mark of a man!

The highest type of friendship is the relation of "brother-friend" or "life-and-death friend." This bond is between man and man, is usually formed in early youth, and can only be broken by death. It is the essence of comradeship and fraternal love, without thought of pleasure or gain, but rather for moral support and inspiration. Each is vowed to die for the other, if need be, and nothing denied the brother-friend, but neither is anything required that is not in accord with the highest conceptions of the Indian mind.

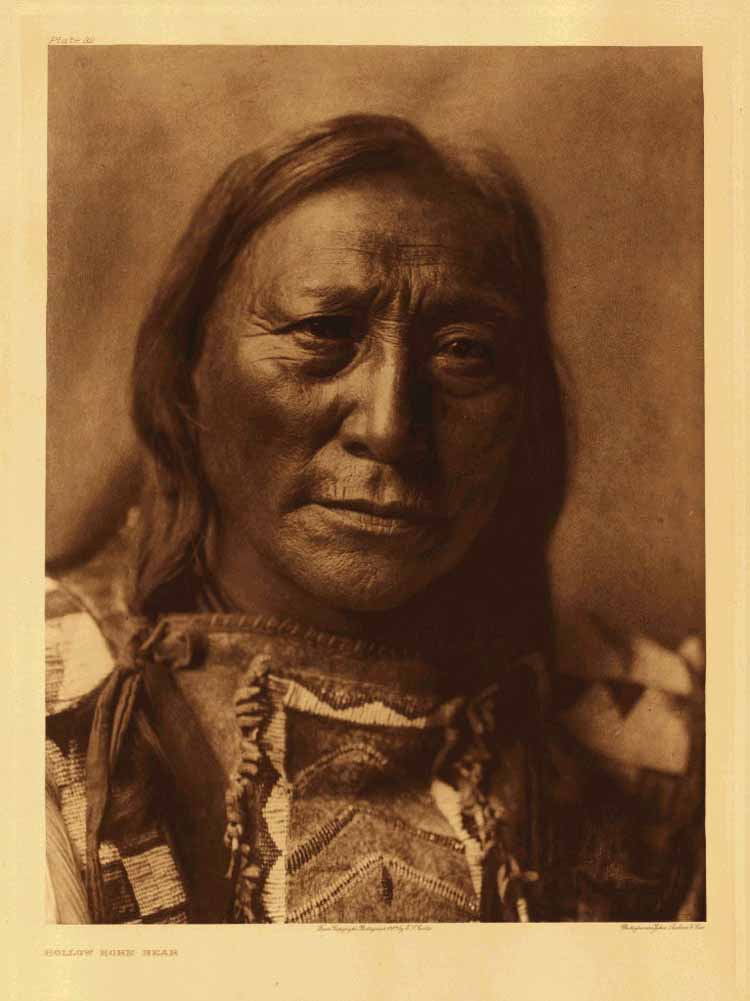

-- Charles Eastman, 1858-1939. The Soul of the Indian.

Publius Papinius Statius was a Roman gentleman and man of letters who died in 96 AD.

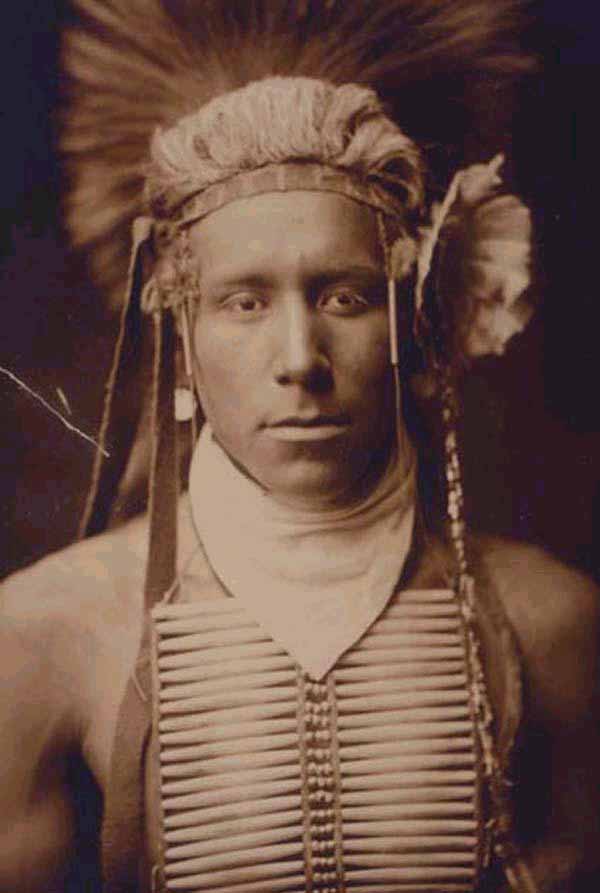

Charles Eastman was raised as a Sioux warrior, and then adopted the ways of the European-Americans and became a physician.

Both wrote tellingly and persuasively of the Way of the Warrior.

In this message thread, we're going to look further at Statius and other writers, like Eastman, to see what they can teach us about being Men and being Warriors.

And I'm posting this both as a reply to the original Statius message thread -- which I strongly encourage you to read -- as well as a separate message thread.

Because I have no doubt that the concept of "The Comradeship of Wounds" -- of the Bonding which takes place through Battle -- is vital for us as Men.

The phrase "the comradeship of wounds" is one I first encountered in Statius.

It's difficult to know whether that phrase was his invention, or whether it preceded him, since so much of the literature of the ancient world has been lost, including almost all the works which Statius would have drawn on when composing the Thebaid.

But the idea of "the comradeship of wounds" is universal.

And we can see it at work in warrior cultures worldwide.

Now, let me say just one more thing about Statius.

I know some of you have a problem with poetry and with being asked to read a Latin poet, even in translation.

But there's a reason we're looking at Statius.

First of all, and what's most important to understand, is that Statius was not some fringe figure.

He wasn't a beatnik.

He wasn't the Allen Ginsburg of Rome.

He was a very mainstream, establishment sort of guy, writing for other mainstream, establishment guys.

Establishment.

So when he writes about two men stripping naked to fight; and says that their mutually-inflicted wounds may foretell a great mutual love; and when he later describes one of those men stripping off his clothes to embrace the corpse of the other -- he's describing behavior which the establishment would have considered not just acceptable but heroic.

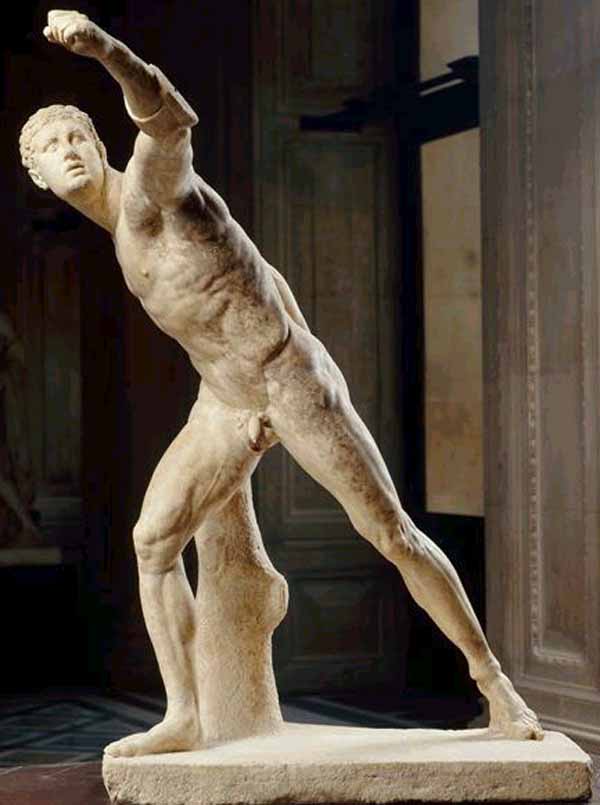

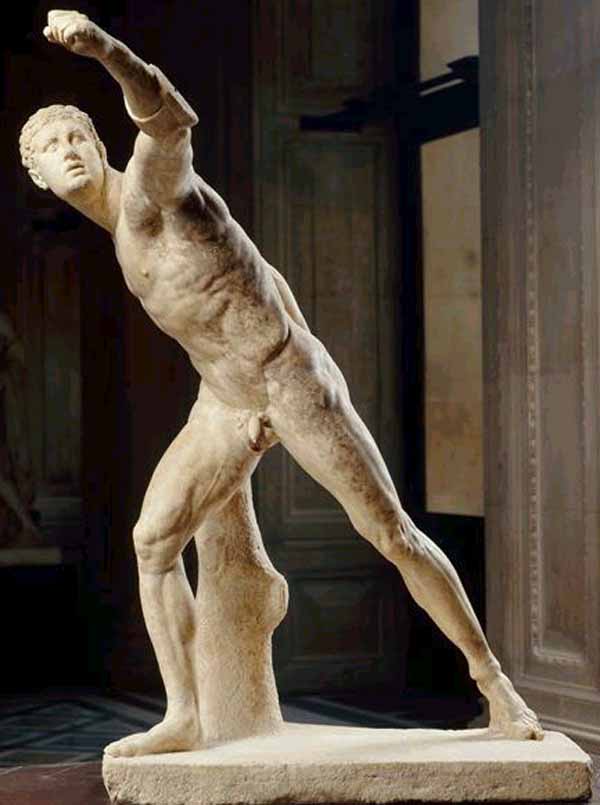

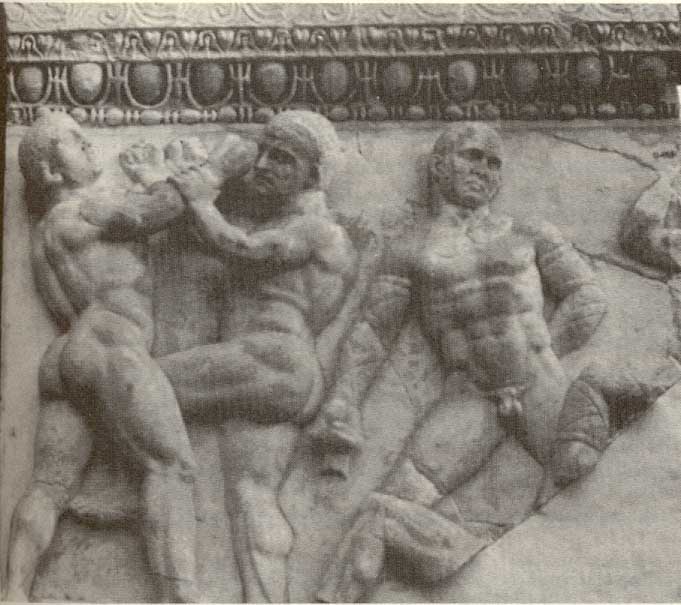

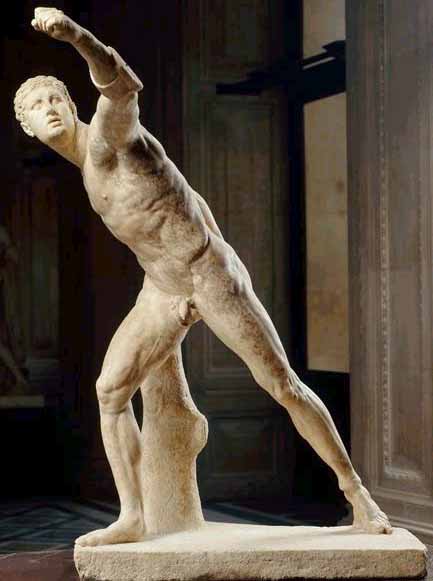

This is a sculpture commonly known as the Borghese Gladiator:

But the figure is NOT a gladiator; he's a warrior.

And the statue is most likely a Roman copy of a Greek original.

It's in remarkably good condition because it was buried -- probably to protect it from barbarians -- and not dug up until the 17th century.

Which is why it's intact.

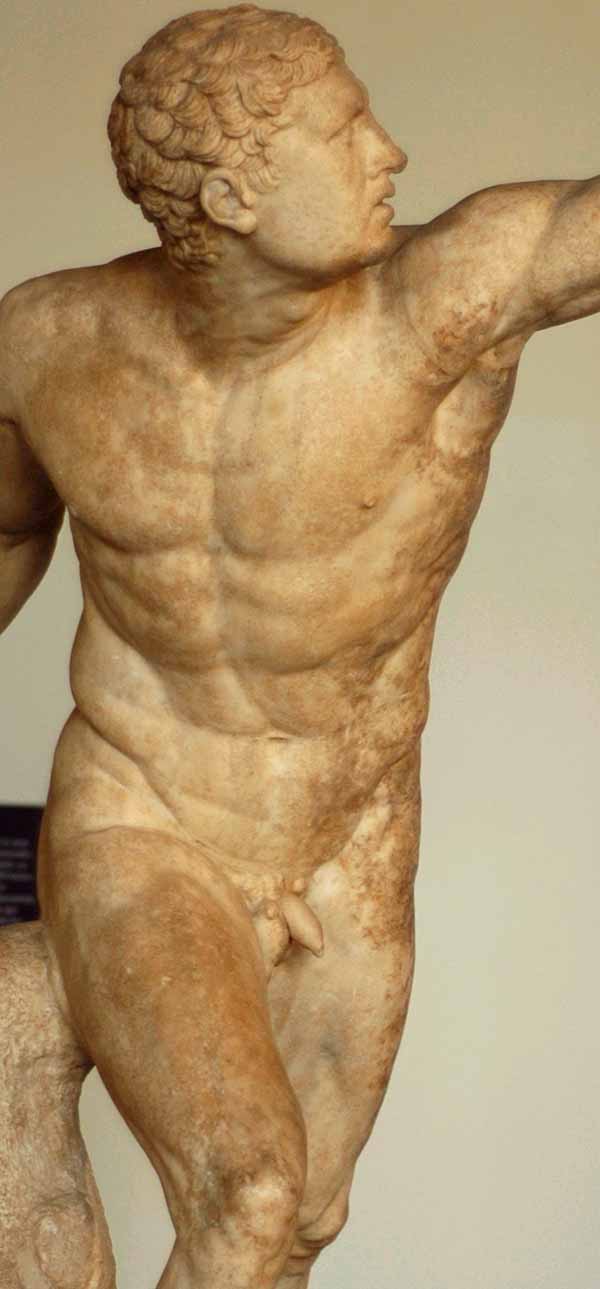

Statius and his friends were surrounded by objects like this -- sculpture, painting, mosaics -- which presented the nude male in glorified and heroic terms.

And not just objects.

Suetonius, tells us, in his biographical account of the first twelve caesars, that the Emperor Augustus, who ruled from 29 BC to 14 AD, liked boxing.

And that when he watched guys box, the guys were nude.

We know they were nude not simply because that's how men boxed in first century Rome, but because Augustus was prudish, and wouldn't let women watch.

Augustus allowed women to attend the gladiatorial games, because gladiators were clothed; but he wouldn't let women attend athletic contests -- boxing, wrestling, and pankration -- because the athletes were nude.

Here's Suetonius:

[Augustus'] chief delight was to watch boxing, particularly when the fighters were Italians -- and not merely professional bouts, in which he often used to pit Italians against Greeks, but slogging matches between untrained roughs in narrow city alleys.

... No women at all were allowed to witness the athletic contests; indeed, when the audience clamoured at the games for a special boxing match to celebrate his appointment as Chief Priest, Augustus postponed this until early the next morning, and issued a proclamation to the effect that women should not attend the Theatre before ten o'clock.

To be brief: Augustus honoured all sorts of professional entertainers by his friendly interest in them; maintained, and even increased, the privileges enjoyed by athletes; banned gladiatorial contests if the defeated fighter were forbidden to plead for mercy ; and amended an ancient law empowering magistrates to punish stage-players wherever and whenever they pleased -- so that they were now competent to deal only with misdemeanours committed at games or theatrical performances. Nevertheless, he insisted on a meticulous observance of regulations during wrestling matches and gladiatorial contests; and was exceedingly strict in checking the licentious behaviour of stage-players.

So: Augustus was, when it came to cultural matters, a conservative -- opposed to licentious behavior and the like.

He was also a conservative who believed that men should be able to wrestle and box naked -- while other men watched them.

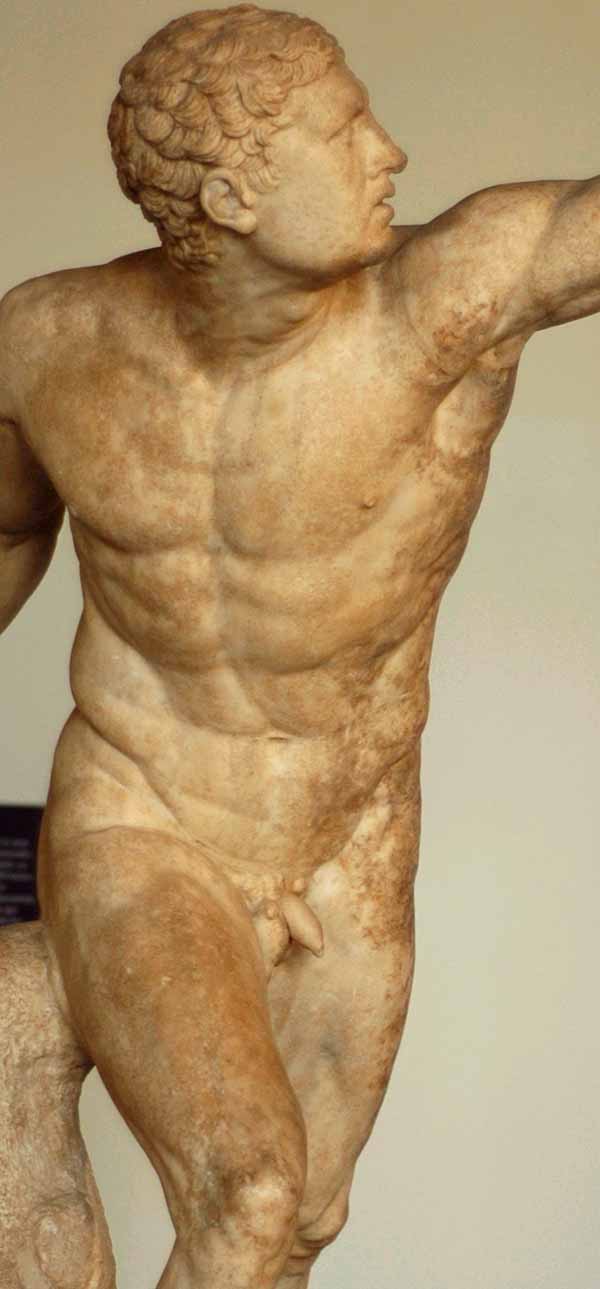

Roman Boxer

Try to imagine a comparable figure in our culture -- someone like George Bush or John McCain -- getting together on an afternoon with a bunch of senators to watch naked men hit each other.

You probably can't imagine it.

If you're like me, the scene is so far removed from probability as to be unimaginable.

To the Romans it was commonplace.

Now: You may not think that boxers are fit subjects for emulation.

But it takes great courage to box -- to fight.

And even more courage to fight before an audience -- before the world.

These Men did so nude.

In the full glory of their Manhood.

So when I ask you to look at the poetry of Statius, it's that you may understand how Men have lived;

and how they might live again.

Bill Weintraub

One of the things I see in my email -- a lot -- and particularly among the gay-identified men -- is a failure of men to acknowledge and deal constructively with their own innate male aggression.

That failure is usually due to self-definition and self-isolation which occurs in adolescence.

I talked about that in my reply to Steve's poignant memoir, My best friend.

In that reply I quoted from my foreign friend, who said:

Men are endowed with a 'seed' of natural masculinity which needs a conducive, supportive social environment to develop / grow to its full potential.

If a positive social environment is denied to a man, or if it is hostile, the natural masculinity will not grow to its full potential. Rather it could be seriously throttled or suppressed.

Masculine male groups and bonds play an extremely important role in the development of physical, mental, emotional and social aspects of natural masculinity. As such they are an important part of the positive environment that all boys should have. An otherwise masculine identified man who is deprived of membership in a masculine male group / bond during his growing years will be less than 1/4th naturally masculine than if he had such an opportunity. Masculine identified boys have a natural tendency to seek to join male-only groups, and it's their natural right.

The masculinity of men flows from their group. It's like their natural masculinity combines and gets manifold when masculine identified men unite. The camaraderie, mutual understanding, support, playing together, learning the ways of the world as a male, dealing with roughs and toughs of life together --- they all help to develop the natural masculinity that exists within him.

An intimate sexual relationship between two masculine men is equally important for the mutual development of their natural masculinity.

So, says my friend, "If a positive social environment is denied to a man, or if it is hostile, the natural masculinity will not grow to its full potential. Rather it could be seriously throttled or suppressed."

And when that happens, it constitutes a devastating failure of development -- and one which, like I say, I see all too often, particularly among gay-identified guys.

For example, I recently received an email from a man -- I'll call him John -- who has a lot of "issues" with aggression and masculinity.

John insisted that men aren't aggressive, they're "assertive."

That's not true.

There's a difference between folks asserting themselves and men being aggressive.

Men are aggressive -- it's one of their defining characteristics.

Fighting spirit, as my foreign friend has said, is the hallmark of masculinity.

And "fighting spirit" is aggression.

John -- the gay-identified guy who wrote to me -- has a lot of sex-wrestling fantasies, though I don't think he's ever done anything sexual, whether wrestling or otherwise, with anyone.

Nevertheless, to preserve his fantasies, he maintains that wrestling isn't aggressive.

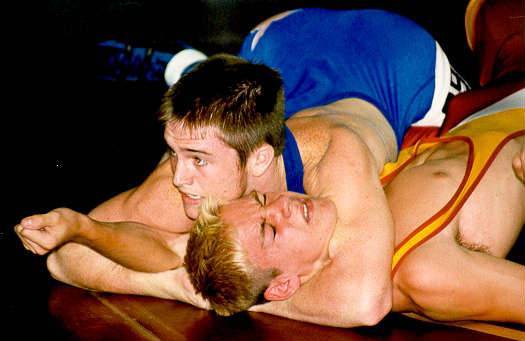

That too is not true.

Wrestling is aggressive.

In wrestling, you seek through physical force to pin your opponent to the mat -- and he resists and seeks to do the same to you.

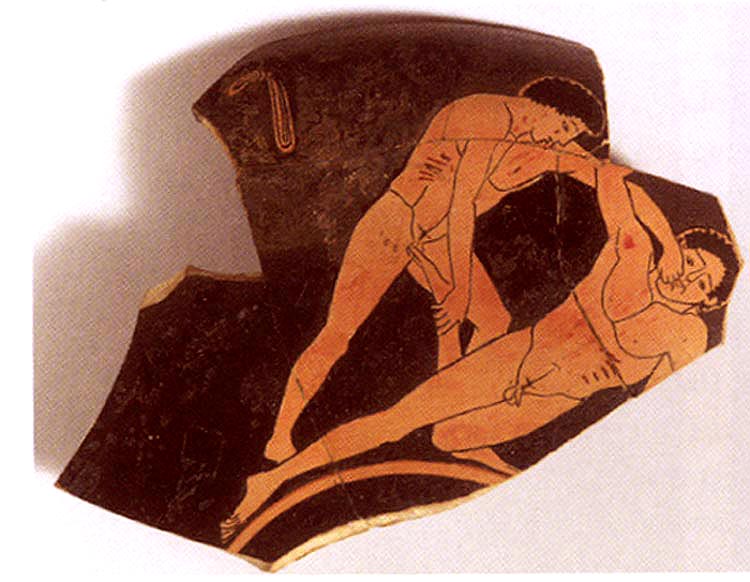

That's aggressive, and as you can see, there's some infliction of pain.

That's part of the experience -- which is shared by both men.

There is however a difference between collegiate / freestyle wrestling, and UFC / mixed martial arts style fighting.

Naked Wrestler and I have talked about this -- and he's a good guide because he's done both.

In collegiate wrestling, the referee is very important.

He awards points -- often, from the point of view of the wrestlers, arbitrarily -- and so, if there's no pin, has a great deal of say in who wins the match.

That's not true in mixed martial arts / UFC.

The goal in mixed martial arts is to get your opponent to submit -- to "tap out."

TAP OUT

And the referee is far less involved.

He's there to make sure the rules are observed and that no one gets badly hurt.

But he doesn't decide who wins -- that's decided, usually, by a submission.

Or by judges.

Does that mean that wrestling is less aggressive than UFC?

Well, you can argue it either way.

There's no doubt that UFC is far closer to a "real-life" fight or street fight.

That's the point of it and that's one of the reasons it's so popular.

But the plain fact is that wrestling is fighting and is one of the most common and most aggressive male-male activities.

And it's universal -- cross-culturally and throughout history.

All combat sports are to some degree cooperative -- which means that the opponents agree on a set of groundrules.

The fighters aren't trying to maim or kill each other -- it's sport.

But they are nevertheless aggressive, and when you're fighting someone, he is de facto *during the fight* and to some degree your enemy -- you're trying to defeat him.

At the end of the bout, as we'll see, you may well hug and become best of friends -- if not more.

But during the fight, you're opponents in aggression.

So it's important that Men understand that and are able to deal with aggression -- their own and that of other Men.

Very important.

And as a practical matter, virtually the only way to learn to do that is through training in actual fighting.

Nothing can take the place of that.

Now -- let's get back to Statius.

When the king comes upon Polynices and Tydeus fighting, he sees

"a sight

Of terror, faces torn, cheeks bruised and smashed,

Streaming with blood..."

He seeks to interrupt that.

So he says:

Your present rage perhaps

Foretokens future love, a memory

To warm your hearts.'Nor were the old man's words

A vain presage. This comradeship of wounds

Issued in such fine trust as Theseus had

Who shared high risks with fierce Pirithous,

Or Pylades who, when Orestes' mind

Was gone, preserved him from the Fury's rage.So then the turmoil in their hearts was soothed

By the king's words...

So: is this poetry or is this reality?

Let's take a look:

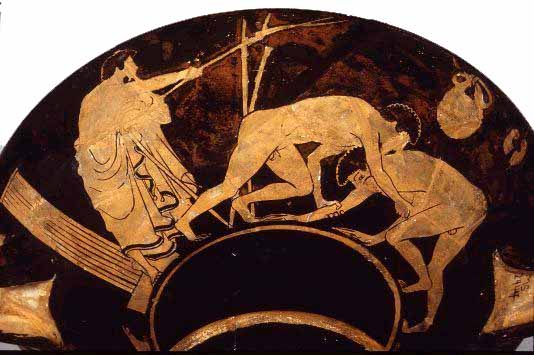

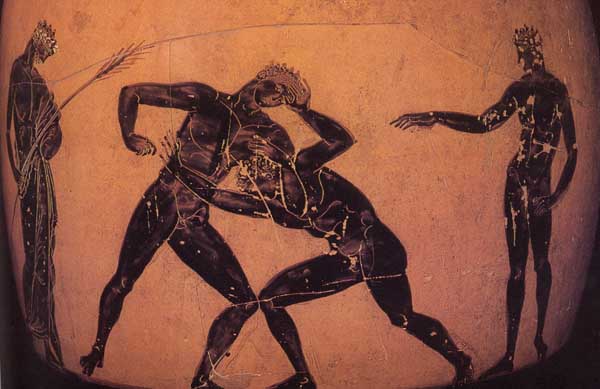

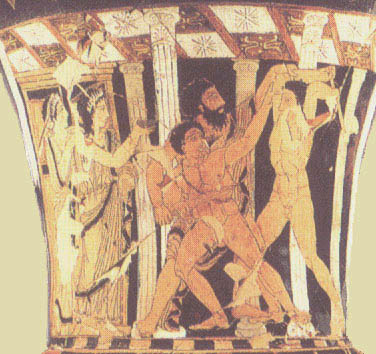

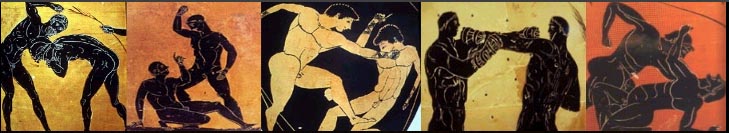

Here are two vase paintings of Warrior-Greek pankratiasts -- today we would call them "mixed martial arts fighters" -- ca 450 BC:

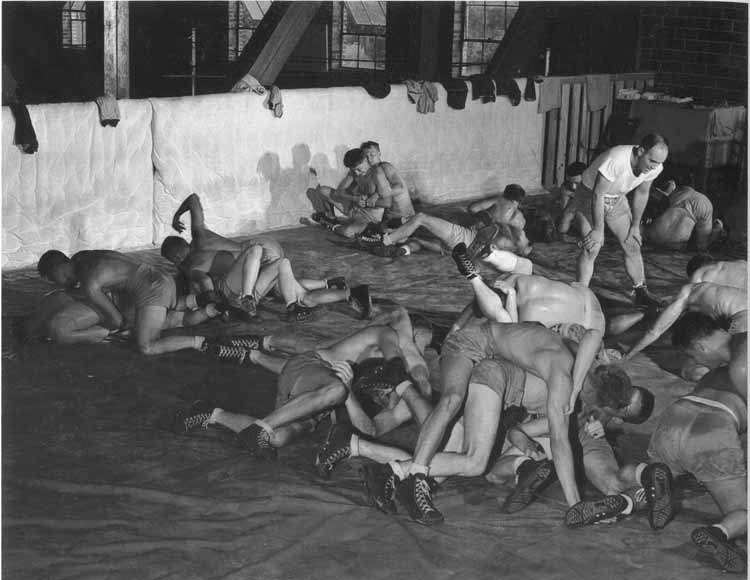

And here are some Warrior-American pankratiasts ca 2007 AD:

Statius says: "faces torn, cheeks bruised and smashed, streaming with blood"

That's not poetry -- that's reality:

He also says "knees are flexed to bruise

Soft sides and loins."

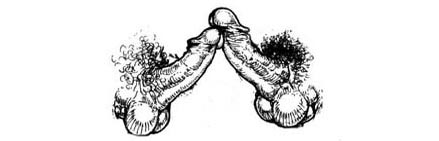

And here's a Roman sculpture of that period representing pankratiasts and boxers:

And we can see that knees are indeed flexed to bruise loins.

So -- Statius is describing reality.

What about the "comradeship of wounds?"

Is that too a reality?

Well, here are a couple of American mixed martial arts / UFC fighters.

Their names are Forrest Griffin and Stephen Bonnar.

The pix are from sherdog.com, which is a site I strongly recommend you visit regularly and frequently.

Why?

Because, on the web, as in life, being determines consciousness.

If you spend all your time looking at analist porn and hanging on hook-up sites, that becomes your consciousness.

Whereas if you spend your time on a fight site like sherdog, where you see MEN practicing a disciplined aggression -- that becomes your consciousness.

So: let's look at some before, during, and after pix of these two mixed martial arts fighters:

Forrest123456789012345678901234567890987654321Stephen

That's the Comradeship of Wounds.

Which *may*, says the king, foretoken future love.

And that is what Polynices and Tydeus would have looked like after their fight, when the king had gotten them cleaned up and staged a banquet at which they could meet his daughters.

"Placed apart the two

Young men recline, their wounds now washed and dry.

Each sees the bruises on the other's cheeks

And each in turn forgives"

So this is not poetry.

Nor is this unique to Forrest and Stephen.

The Comradeship of Wounds.

It's a comradeship which every man must experience.

Statius, remember, was writing for an audience which knew and understood fighting.

It was a commonplace of their lives.

So that he could not, as it were, pull his punches.

He had to represent not just the physical act but the emotional impact as well.

And that's what he's done.

And that's why his message is so important.

It's also why a man like Hadrian was so fond of this story.

Because for him as a military man, and as a man who openly loved another, it presented profound truths.

First a brief pause for threatening words, then rage

Swelled as taunts flew, and both sprang to their feet

And bared their bodies and stood stripped to fight.

In the poem, Statius has his characters strip to fight.

How common is that?

I recently read a memoir by an African youth who'd been kidnapped and forced to go to war as a child-soldier.

His country was in a civil war, and after his parents were killed by one side, he was snatched, at the age of 12, by the other, and made to soldier -- with a gun and for real.

Which he did -- for a couple years.

It was kill or be killed and he did kill.

Finally a philanthropic organization succeeded in wresting him and a bunch of other child-soldiers away from the contending factions.

They were put in a camp.

But their keepers didn't bother to separate the boys who'd been trying to kill each other just days before.

So there were fights.

As one fight was about to begin, the memoirist said, "He pulled off his shirt, which is what we do when we're about to fight."

Now of course, like the archaic Greeks, these were very poor people.

Who did not want their clothing destroyed in a fight.

Nevertheless, it's difficult not to see the pulling off of the shirt as a signal and a challenge.

A signal.

Probably a universal male signal.

And that's why Statius has his characters do it.

They strip to fight -- because that's what men do.

First a brief pause for threatening words, then rage

Swelled as taunts flew, and both sprang to their feet

And bared their bodies and stood stripped to fight.

Is there a sexual content to that act?

This is from Dara Molloy, a former Irish Marist priest who left the church to become a "Celtic Priest" -- and I'm indebted to Frances for this quote:

This is a long-standing practice [soldiers abstaining from sex with women] among soldiers at war and is to be found among many different cultures. In the Celtic tradition, there is the story of Cuchulainn separating himself from women before going to battle. Celtic warriors went into battle naked, apart from the torc on their necks. Before going into battle they worked themselves up into a frenzy, causing an erection. Battle for the Celtic warriors was an orgasmic experience. For this reason, they preserved their sexual energies for battle...

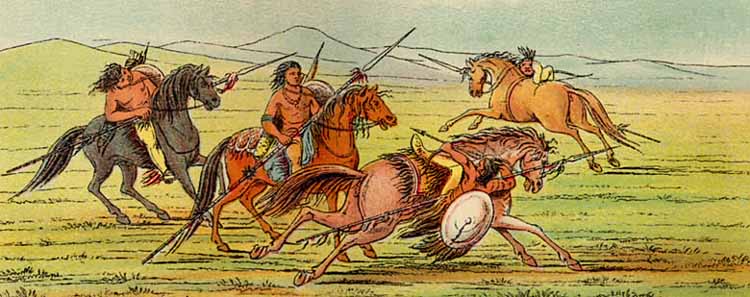

Celtic battle frenzy

The Greeks and the Romans, who both fought the Celts, were well aware of this.

Here's the famous sculpture known as the Dying Gaul, which was the creation of a Greek sculptor of the Hellenistic era:

Here are American servicemen during WW II:

Of course they're not nude -- but they have stripped off their shirts.

And here we are back with Tydeus and Polynices:

The Fight

Polynices on the right, Tydeus to the left, and the King in the center

This too is part of the comradeship of wounds.

The agoge was the Spartan system for turning boys into Warriors -- that's to say, for teaching them about the comradeship of wounds.

All Warriordom -- all Warrior societies -- have such systems.

Boys learn and are trained through adult mentors, and through their interactions with other boys and men, as they're growing up in a homosocial -- that is, predominately same-sex -- environment.

For example, Eastman notes of his young Sioux that "At the age of about eight years, if he is a boy, [his mother] turns him over to his father for more Spartan training."

"Spartan" of course is right -- that's what the Spartans did, though they started their boys at age seven.

In this section of The Comradeship of Wounds, we're going to look at two versions of the Warrior's Boyhood.

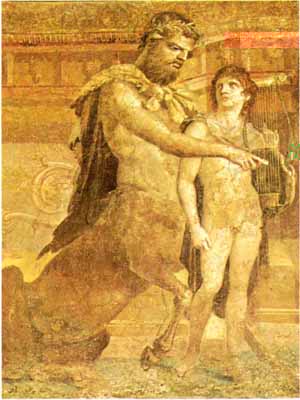

The first account is mythical -- it's Statius' telling of the boyhood of the great Greek hero Achilles, who was raised by the wise warrior centaur Chiron.

This account by Statius is the last thing he wrote.

He planned a far larger book, to be called the Achilleid, about the life of Achilles.

But he didn't live to finish it.

All he had time to tell us about was Achilles' boyhood.

Here's an excerpt from the Achilleid, in a wonderful colloquial translation by David Slavitt:

Diomedes changes the subject. "Confide in us as your friends

and tell us about your childhood and how you were reared in the centaur's

famous and difficult school. What were the stories he told you

of the ancient heroes' deeds? What did he make you do?

How did he train you in strength, endurance, and skill? In fairness,

and for our exertions, our trouble in coming to fetch you from Scyros,

tell us whatever you can of Chiron's wonderful methods."No one dislikes talking about himself, but Achilles'

modesty prevents him from appearing to boast. Even so,

having been asked in this way, he feels compelled to respond:"I started with Chiron early, as an infant really. I'm told

I was never given what children usually eat. He fed me

only when I was extremely hungry, and then he gave me

the entrails of lions and wolves for my baby teeth to chew on.

For as long as I can remember, he took me with him whenever

he ventured into the forests. I'd run along beside him

on my little legs and try to keep up with his powerful stride.

I never felt any fear of wild beasts. He taught me

to laugh in delight when I saw them; he gave me a quiver and bow,

and a spear, and I learned the joys of the chase. I lived in the woods,

where I came to know the roar of the waterfalls and the hush

of the empty glade. To the heat of the summer sun, or the bitter

cold of the winter's night, I became accustomed. That other

children's lives were different, I had no idea. They slept

on beds that weakened their bones, but I lay down on the cold

hard ground with my master's flank as my only pillow.At twelve, I could outrun a deer and bring it down without nets

or packs of hounds to help me. I was faster than any horse-

or even a centaur, for Chiron used to gallop behind me

and tease, and we'd race together over the meadows, running

for miles until I was utterly spent. Then he'd praise my effort

and hoist me up on his back and carry me home. He taught me

how to walk out on new-formed ice of a stream in winter,

taking my steps lightly so I didn't break through to get soaked

in the bone-chilling water. ..I thought it was fun to do this,

a game, but there were rules I learned: it wasn't sporting

to go for the gentle doe or the timid lynx. Brave boys

only hunt bears in their caves, or wild boars with their sharp

tusks. I was also permitted lions up in their mountain

lairs, and, I think, tigers -- which are rare in this part of the world.

I'd go out on the trails, and Chiron would wait at the cave

to welcome me home, stained with the blood of the beasts and my own.He'd look me over, check my bag, and inspect my weapons,

and only then embrace me and patch me up. He was training

my spirit, of course, but he also taught me particular skills.There was more or less formal drill in the use of Paeonian darts,

and I learned to throw the Macedonian javelin, wield

the Sarmatian pike, the curved sword of the Getans, the huge

Gelonian bow, and the Balearic sling-shot you have to swing

around and around your head as you figure the arc to the target.Aside from these various weapons, there was also basic training

in jumping, climbing, running, and hand-eye coordination.

He'd give me a shield and then throw stones for me to fend off.

He taught me not to inhale as I ran through fires. He made me

stand still, plant myself like a rock, and then come charging

with a team of horses I'd have to grab and stop in their tracks.

Or he'd put me into a river, the Spercheus' rapids, for instance,

when spring rains had it flooded -- I'd stand there and fight the current,

the water itself, but also the branches and trunks of trees,

and fair-sized boulders that rolled down in the churning water.

With all his four legs, he could barely stand there himself, but I learned

to do it, at least for a while, on just these two. He'd watch

from the shore, shouting insults and laughing whenever I fell.

I'd pick myself up and do it again and again, till he signaled

I'd lasted long enough. I trained with the Spartan quoit,

flinging the iron circle into the clouds. I practiced

the wrestling holds, and I'd box with the cestus and bared fists --

but that was for relaxation.There were also studies -- I practiced

playing the lyre and singing the songs of the gods and giants

and heroes of olden times. He taught me the arts of healing,

which were the leaves and grasses from which to get juices to soothe

one disease or another, or staunch blood, or for sleep.

He showed me which kinds of infections to lance and which do better

with herbal salves. And then, in the evenings, he used to give lessons

in ethics, theology, law, with discussions of justice and virtue

and the ways of the gods of Olympus, of centaurs on lower mountains,

and of men, too. I remember those evenings with gratitude now,

and the fine talk that kept going later and later. I miss that

most of all and believe it was what my mother intended

when she first gave the baby I was into his hands."

The wind was slackening off as the keel ground up on the shore. ..

[End of poem -- Here Statius died]

Now, of course, Achilles and Chiron are mythological creatures.

But the boyhood Statius describes in 96 AD -- and remember that Statius had access to literature and texts which have since vanished -- is remarkably close to the Sioux warrior boyhood which Charles Eastman described 1800 years later.

Achilles, being mythic, has just one mentor -- Chiron -- to guide him.

The Sioux, on the other hand, like the Spartans themselves, rely heavily on other boys as well as adult mentors.

As my foreign friend says:

The masculinity of men flows from their group. It's like their natural masculinity combines and gets manifold when masculine identified men unite. The camaraderie, mutual understanding, support, playing together, learning the ways of the world as a male, dealing with roughs and toughs of life together --- they all help to develop the natural masculinity that exists within him.

And we'll see that among Eastman's boyhood friends, "dealing with the roughs and toughs of life together" is an essential part of the training.

Remember too as you're reading Eastman that when Ben Franklin went to France and saw his first ancient Greek sculpture, he said, "He looks like an Indian brave."

Not surprising.

Because in many ways the boyhood of a Sioux warrior -- and that of a Spartan or any other ancient Greek warrior -- were very similar.

Here's Eastman:

An Indian Boyhood

I

Earliest Recollections

I: Hadakah, "The Pitiful Last"

WHAT boy would not be an Indian for a while when he thinks of the freest life in the world? This life was mine. Every day there was a real hunt. There was real game. Occasionally there was a medicine dance away off in the woods where no one could disturb us, in which the boys impersonated their elders, Brave Bull, Standing Elk, High Hawk, Medicine Bear, and the rest. They painted and imitated their fathers and grandfathers to the minutest detail, and accurately too, because they had seen the real thing all their lives.

We were not only good mimics but we were close students of nature. We studied the habits of animals just as you study your books. We watched the men of our people and represented them in our play; then learned to emulate them in our lives.

No people have a better use of their five senses than the children of the wilderness. We could smell as well as hear and see. We could feel and taste as well as we could see and hear. Nowhere has the memory been more fully developed than in the wild life, and I can still see wherein I owe much to my early training.

...

Indian children were trained so that they hardly ever cried much in the night. This was very expedient and necessary in their exposed life. In my infancy it was my grandmother's custom to put me to sleep, as she said, with the birds, and to waken me with them, until it became a habit. She did this with an object in view. An Indian must always rise early. In the first place, as a hunter, he finds his game best at daybreak. Secondly, other tribes, when on the war-path, usually make their attack very early in the morning. Even when our people are moving about leisurely, we like to rise before daybreak, in order to travel when the air is cool, and unobserved, perchance, by our enemies.

As a little child, it was instilled into me to be silent and reticent. This was one of the most important traits to form in the character of the Indian. As a hunter and warrior it was considered absolutely necessary to him, and was thought to lay the foundations of patience and self-control. There are times when boisterous mirth is indulged in by our people, but the rule is gravity and decorum.

After all, my babyhood was full of interest and the beginnings of life's realities. The spirit of daring was already whispered into my ears. The value of the eagle feather as worn by the warrior had caught my eye. One day, when I was left alone, at scarcely two years of age, I took my uncle's war bonnet and plucked out all its eagle feathers to decorate my dog and myself. So soon the life that was about me had made its impress, and already I desired intensely to comply with all of its demands.

...

II

An Indian Boy's Training

IT is commonly supposed that there is no systematic education of their children among the aborigines of this country. Nothing could be farther from the truth. All the customs of this primitive people were held to be divinely instituted, and those in connection with the training of children were scrupulously adhered to and transmitted from one generation to another.

...

Scarcely was the embyro warrior ushered into the world, when he was met by lullabies that speak of wonderful exploits in hunting and war. Those ideas which so fully occupied his mother's mind before his birth are now put into words by all about the child, who is as yet quite unresponsive to their appeals to his honor and ambition. He is called the future defender of his people, whose lives may depend upon his courage and skill. If the child is a girl, she is at once addressed as the future mother of a noble race.

In hunting songs, the leading animals are introduced; they come to the boy to offer their bodies for the sustenance of his tribe. The animals are regarded as his friends, and spoken of almost as tribes of people, or as his cousins, grandfathers and grandmothers. The songs of wooing, adapted as lullabies, were equally imaginative, and the suitors were often animals personified, while pretty maidens were represented by the mink and the doe.

Very early, the Indian boy assumed the task of preserving and transmitting the legends of his ancestors and his race. Almost every evening a myth, or a true story of some deed done in the past, was narrated by one of the parents or grandparents, while the boy listened with parted lips and glistening eyes. On the following evening, he was usually required to repeat it. If he was not an apt scholar, he struggled long with his task; but, as a rule, the Indian boy is a good listener and has a good memory, so that the stories were tolerably well mastered. The household became his audience, by which he was alternately criticized and applauded.

This sort of teaching at once enlightens the boy's mind and stimulates his ambition. His conception of his own future career becomes a vivid and irresistible force. Whatever there is for him to learn must be learned; whatever qualifications are necessary to a truly great man he must seek at any expense of danger and hardship. Such was the feeling of the imaginative and brave young Indian. It became apparent to him in early life that he must accustom himself to rove alone and not to fear or dislike the impression of solitude.

It seems to be a popular idea that all the characteristic skill of the Indian is instinctive and hereditary. This is a mistake. All the stoicism and patience of the Indian are acquired traits, and continual practice alone makes him master of the art of woodcraft. Physical training and dieting were not neglected. I remember that I was not allowed to have beef soup or any warm drink. The soup was for the old men. General rules for the young were never to take their food very hot, nor to drink much water.

My uncle, who educated me up to the age of fifteen years, was a strict disciplinarian and a good teacher. When I left the teepee in the morning, he would say: "Hakadah, look closely to everything you see"; and at evening, on my return, he used often to catechize me for an hour or so.

"On which side of the trees is the lighter-colored bark? On which side do they have most regular branches?"

It was his custom to let me name all the new birds that I had seen during the day. I would name them according to the color or the shape of the bill or their song or the appearance and locality of the nest -- in fact, anything about the bird that impressed me as characteristic. I made many ridiculous errors, I must admit. He then usually informed me of the correct name. Occasionally I made a hit and this he would warmly commend.

He went much deeper into this science when I was a little older, that is, about the age of eight or nine years. He would say, for instance:

"How do you know that there are fish in yonder lake?"

"Because they jump out of the water for flies at mid-day."

He would smile at my prompt but superficial reply.

"What do you think of the little pebbles grouped together under the shallow water? and what made the pretty curved marks in the sandy bottom and the little sand-banks? Where do you find the fish-eating birds? Have the inlet and the outlet of a lake anything to do with the question?"

He did not expect a correct reply at once to all the voluminous questions that he put to me on these occasions, but he meant to make me observant and a good student of nature.

"Hakadah," he would say to me, "you ought to follow the example of the shunktokecha (wolf). Even when he is surprised and runs for his life, he will pause to take one more look at you before he enters his final retreat. So you must take a second look at everything you see.

"It is better to view animals unobserved. I have been a witness to their courtships and their quarrels and have learned many of their secrets in this way. I was once the unseen spectator of a thrilling battle between a pair of grizzly bears and three buffaloes--a rash act for the bears, for it was in the moon of strawberries, when the buffaloes sharpen and polish their horns for bloody contests among themselves.

"I advise you, my boy, never to approach a grizzly's den from the front, but to steal up behind and throw your blanket or a stone in front of the hole. He does not usually rush for it, but first puts his head out and listens and then comes out very indifferently and sits on his haunches on the mound in front of the hole before he makes any attack. While he is exposing himself in this fashion, aim at his heart. Always be as cool as the animal himself." Thus he armed me against the cunning of savage beasts by teaching me how to outwit them.

"In hunting," he would resume, "you will be guided by the habits of the animal you seek. Remember that a moose stays in swampy or low land or between high mountains near a spring or lake, for thirty to sixty days at a time. Most large game moves about continually, except the doe in the spring; it is then a very easy matter to find her with the fawn. Conceal yourself in a convenient place as soon as you observe any signs of the presence of either, and then call with your birchen doe-caller.

"Whichever one hears you first will soon appear in your neighborhood. But you must be very watchful, or you may be made a fawn of by a large wild-cat. They understand the characteristic call of the doe perfectly well.

"When you have any difficulty with a bear or a wild-cat--that is, if the creature shows signs of attacking you--you must make him fully understand that you have seen him and are aware of his intentions. If you are not well equipped for a pitched battle, the only way to make him retreat is to take a long sharp-pointed pole for a spear and rush toward him. No wild beast will face this unless he is cornered and already wounded. These fierce beasts are generally afraid of the common weapon of the larger animals -- the horns, and if these are very long and sharp, they dare not risk an open fight.

"There is one exception to this rule -- the grey wolf will attack fiercely when very hungry. But their courage depends upon their numbers; in this they are like white men. One wolf or two will never attack a man. They will stampede a herd of buffaloes in order to get at the calves; they will rush upon a herd of antelopes, for these are helpless; but they are always careful about attacking man."

Of this nature were the instructions of my uncle, who was widely known at that time as among the greatest hunters of his tribe.

All boys were expected to endure hardship without complaint. In savage warfare, a young man must, of course, be an athlete and used to undergoing all sorts of privations. He must be able to go without food and water for two or three days without displaying any weakness, or to run for a day and a night without any rest. He must be able to traverse a pathless and wild country without losing his way either in the day or nighttime. He cannot refuse to do any of these things if he aspires to be a warrior.

Sometimes my uncle would waken me very early in the morning and challenge me to fast with him all day. I had to accept the challenge. We blackened our faces with charcoal, so that every boy in the village would know that I was fasting for the day. Then the little tempters would make my life a misery until the merciful sun hid behind the western hills.

I can scarcely recall the time when my stern teacher began to give sudden war-whoops over my head in the morning while I was sound asleep. He expected me to leap up with perfect presence of mind, always ready to grasp a weapon of some sort and to give a shrill whoop in reply. If I was sleepy or startled and hardly knew what I was about, he would ridicule me and say that I need never expect to sell my scalp dear. Often he would vary these tactics by shooting off his gun just outside of the lodge while I was yet asleep, at the same time giving blood-curdling yells. After a time I became used to this.

When Indians went upon the war-path, it was their custom to try the new warriors thoroughly before coming to an engagement. For instance, when they were near a hostile camp, they would select the novices to go after the water and make them do all sorts of things to prove their courage. In accordance with this idea, my uncle used to send me off after water when we camped after dark in a strange place. Perhaps the country was full of wild beasts, and, for aught I knew, there might be scouts from hostile bands of Indians lurking in that very neighborhood.

Yet I never objected, for that would show cowardice. I picked my way through the woods, dipped my pail in the water and hurried back, always careful to make as little noise as a cat. Being only a boy, my heart would leap at every crackling of a dry twig or distant hooting of an owl, until, at last, I reached our teepee. Then my uncle would perhaps say: "Ah, Hakadah, you are a thorough warrior," empty out the precious contents of the pail, and order me to go a second time.

Imagine how I felt! But I wished to be a brave man as much as a white boy desires to be a great lawyer or even President of the United States. Silently I would take the pail and endeavor to retrace my footsteps in the dark.

With all this, our manners and morals were not neglected. I was made to respect the adults and especially the aged. I was not allowed to join in their discussions, nor even to speak in their presence, unless requested to do so. Indian etiquette was very strict, and among the requirements was that of avoiding the direct address. A term of relationship or some title of courtesy was commonly used instead of the personal name by those who wished to show respect. We were taught generosity to the poor and reverence for the "Great Mystery." Religion was the basis of all Indian training.

I recall to the present day some of the kind warnings and reproofs that my good grandmother was wont to give me. "Be strong of heart--be patient!" she used to say. She told me of a young chief who was noted for his uncontrollable temper. While in one of his rages he attempted to kill a woman, for which he was slain by his own band and left unburied as a mark of disgrace -- his body was simply covered with green grass. If I ever lost my temper, she would say:

"Hakadah, control yourself, or you will be like that young man I told you of, and lie under a green blanket!"

In the old days, no young man was allowed to use tobacco in any form until he had become an acknowledged warrior and had achieved a record. If a youth should seek a wife before he had reached the age of twenty-two or twenty-three, and been recognized as a brave man, he was sneered at and considered an ill-bred Indian. He must also be a skillful hunter. An Indian cannot be a good husband unless he brings home plenty of game.

These precepts were in the line of our training for the wild life.

III

My Plays and Playmates

I: Games and Sports

THE Indian boy was a prince of the wilderness. He had but very little work to do during the period of his boyhood. His principal occupation was the practice of a few simple arts in warfare and the chase. Aside from this, he was master of his time.

Whatever was required of us boys was quickly performed: then the field was clear for our games and plays. There was always keen competition among us. We felt very much as our fathers did in hunting and war -- each one strove to excel all the others.

It is true that our savage life was a precarious one, and full of dreadful catastrophes; however, this never prevented us from enjoying our sports to the fullest extent. As we left our teepees in the morning, we were never sure that our scalps would not dangle from a pole in the afternoon! It was an uncertain life, to be sure. Yet we observed that the fawns skipped and played happily while the gray wolves might be peeping forth from behind the hills, ready to tear them limb from limb.

Our sports were molded by the life and customs of our people; indeed, we practiced only what we expected to do when grown. Our games were feats with the bow and arrow, foot and pony races, wrestling, swimming and imitation of the customs and habits of our fathers. We had sham fights with mud balls and willow wands; we played lacrosse, made war upon bees, shot winter arrows (which were used only in that season), and coasted upon the ribs of animals and buffalo robes.

No sooner did the boys get together than, as a usual thing, they divided into squads and chose sides; then a leading arrow was shot at random into the air. Before it fell to the ground a volley from the bows of the participants followed. Each player was quick to note the direction and speed of the leading arrow and he tried to send his own at the same speed and at an equal height, so that when it fell it would be closer to the first than any of the others.

It was considered out of place to shoot by first sighting the object aimed at. This was usually impracticable in actual life, because the object was almost always in motion, while the hunter himself was often upon the back of a pony at full gallop. Therefore, it was the off-hand shot that the Indian boy sought to master. There was another game with arrows that was characterized by gambling, and was generally confined to the men.

The races were an every-day occurrence. At noon the boys were usually gathered by some pleasant sheet of water and as soon as the ponies were watered, they were allowed to graze for an hour or two, while the boys stripped for their noonday sports. A boy might say to some other whom he considered his equal:

"I can't run; but I will challenge you to fifty paces."

A former hero, when beaten, would often explain his defeat by saying: " I drank too much water."

Boys of all ages were paired for a "spin," and the little red men cheered on their favorites with spirit.

As soon as this was ended, the pony races followed. All the speedy ponies were picked out and riders chosen. If a boy declined to ride, there would be shouts of derision.

Last of all came the swimming. A little urchin would hang to his pony's long tail, while the latter, with only his head above water, glided sportively along. Finally the animals were driven into a fine field of grass and we turned our attention to other games.

Lacrosse was an older game and was confined entirely to the Sisseton and Santee Sioux. Shinny, such as is enjoyed by white boys on the ice, is still played on the open prairie by the western Sioux. The "moccasin game," although sometimes played by the boys, was intended mainly for adults.

The "mud-and-willow" fight was rather a severe and dangerous sport. A lump of soft clay was stuck on the end of a limber and springy willow wand and thrown as boys throw apples from sticks, with considerable force. When there were fifty or a hundred players on each side, the battle became warm; but anything to arouse the bravery of Indian boys seemed to them a good and wholesome diversion.

Wrestling was largely indulged in by us all. It may seem odd,, but wrestling was done by a great many boys at once -- from ten to any number on a side. It was really a battle, in which each one chose his opponent. The rule was that if a boy sat down, he was let alone, but as long as he remained standing within the field, he was open to an attack. No one struck with the hand, but all manner of tripping with legs and feet and butting with the knees was allowed. Altogether it was an exhausting pastime -- fully equal to the American game of football and only the young athlete could really enjoy it.

One of our most curious sports was a war upon the nests of wild bees. We imagined ourselves about to make an attack upon the Ojibways or some tribal foe. We all painted and stole cautiously upon the nest; then, with a rush and war-whoop, sprang upon the object of our attack and endeavored to destroy it. But it seemed that the bees were always on the alert and never entirely surprised, for they always raised quite as many scalps as did their bold assailants! After the onslaught upon the nest was ended, we usually followed it by a pretended scalp dance.

On the occasion of my first experience in this mode of warfare, there were two other little boys who were also novices. One of them particularly was really too young to indulge in an exploit of that kind. As it was the custom of our people, when they killed or wounded an enemy on the battle field, to announce the act in a loud voice, we did the same. My friend, Little Wound (as I will call him, for I do not remember his name), being quite small, was unable to reach the nest until it had been well trampled upon and broken and the insects had made a counter charge with such vigor as to repulse and scatter our numbers in every direction. However, he evidently did not want to retreat without any honors; so he bravely jumped upon the nest and yelled:

"I, the brave Little Wound, to-day kill the only fierce enemy!"

Scarcely were the last words uttered when he screamed as if stabbed to the heart. One of his older companions shouted:

"Dive into the water! Run! Dive into the water!" for there was a lake near by. This advice he obeyed.

When we had reassembled and were indulging in our mimic dance, Little Wound was not allowed to dance. He was considered not to be in existence -- he had been killed by our enemies, the Bee tribe. Poor little fellow! His swollen face was sad and ashamed as he sat on a fallen log and watched the dance. Although he might well have styled himself one of the noble dead who had died for their country, yet he was not unmindful that he had screamed, and this weakness would be apt to recur to him many times in the future.

We had some quiet plays which we alternated with the more severe and warlike ones. Among them were throwing wands and snow-arrows. In the winter we coasted much. We had no "double-rippers" or toboggans, but six or seven of the long ribs of a buffalo, fastened together at the larger end, answered all practical purposes. Some- times a strip of bass-wood bark, four feet long and about six inches wide, was used with considerable skill. We stood on one end and held the other, using the slippery inside of the bark for the outside, and thus coasting down long hills with remarkable speed.

...

We loved to play in the water. When we had no ponies, we often had swimming matches of our own and sometimes made rafts with which we crossed lakes and rivers. It was a common thing to "duck" a young or timid boy or to carry him into deep water to struggle as best he might.

...

We had many curious wild pets. There were young foxes, bears, wolves, raccoons, fawns, buffalo calves and birds of all kinds, tamed by various boys. My pets were different at different times, but I particularly remember one. I once had a grizzly bear for a pet and so far as he and I were concerned, our relations were charming and very close. But I hardly know whether he made more enemies for me or I for him. It was his habit to treat every boy unmercifully who injured me. He was despised for his conduct in my interest and I was hated on account of his interference.

II: My Playmates

CHATANNA was the brother with whom I passed much of my early childhood. From the time that I was old enough to play with boys, this brother was my close companion. He was a handsome boy, and an affectionate comrade. We played together, slept together and ate together; and as Chatanna was three years the older, I naturally looked up to him as to a superior.

One spring my uncle took Chatanna to the Canadian trading-post on the Assiniboine river, where he went to trade off his furs for ammunition and other commodities. When he came back, my brother was not with him!

At first my fears were even worse than the reality. The facts were these: A Canadian with whom my uncle had traded much had six daughters and no son; and when he saw this handsome and intelligent little fellow, he at once offered to adopt him.

"I have no boy in my family," said he, "and I will deal with him as with a son. I am always in these regions trading; so you can see him two or three times in a year."

He further assured my uncle that the possession of the boy would greatly strengthen their friendship. The matter was finally agreed upon. At first Chatanna was unwilling, but as we were taught to follow the advice of our parents and guardians, he was obliged to yield.

This was a severe blow to me, and for a long time I could not be consoled. Uncheedah was fully in sympathy with my distress. She argued that the white man's education was not desirable for her boys; in fact, she urged her son so strongly to go back after Chatanna that he promised on his next visit to the post to bring him home again.

But the trader was a shrewd man. He immediately moved to another part of the country; and I never saw my Chatanna, the companion of my childhood, again! We learned afterward that he grew up and was married; but one day he lost his way in a blizzard and was frozen to death.

...

In the Thebaid, Polynices' brother-of-the-heart Tydeus is killed in battle.

And he laments.

Then Rumour roamed across the battlefield,

Swift news from troop to troop, a messenger

More urgent when the tale is woe, until

She glided to the startled ears of him

To whom her words would bring the greatest loss,

Polynices. He froze, his ready tears

Congealed. Belief came slow, for Tydeus' fine

Valour, known all too well, gave credence to

His death and yet forbade it. But when sure

Warrant confirmed the tragedy, on eyes

And mind night swooped; his blood was blocked; his limbs,

His weapons, dropped; tears drenched his soaring casque

And his shield, falling, rested on his greaves.In grief he went, dragging weak knees, his spear

Trailing, burdened it seemed by countless wounds

And maimed in every limb. His comrades stood

Askance and pointed to their friend with groans.At last, discarding arms he scarce could wield,

He fell, stripped, on the now drained body of

His peerless friend and poured his weeping words:'Tydeus, last, greatest hope of my campaign,

Is this my thanks, is this my fit reward,

That you lie bare on Cadmus' hated soil

And I survive? Now evermore I'll be

Exiled and banished, since I've lost, alas,

My other, better, brother. I'll not seek

The lot that fell for me so long ago,

That guilty kingdom's perjured diadem.

What worth are joys so dearly bought, what worth

A sceptre that your hand will not bestow?

Go, my good friends, leave me to face my fierce

Brother alone. There's no need to attempt

Fresh battles, wasting deaths. I beg you, go!

What can you give me now that's greater? I

Have squandered Tydeus. By what death shall I

Atone for that? O Argos! O my bride's

Great father! And the fine dispute of that

First night, those blows exchanged, and our brief rage,

The pledge of long affection! Why was I

Not slain then on that threshold by your sword --

You had the power. And, yes, on my behalf

Gladly you made your way to Thebes and my

Brother's vile palace, whence no one but you

Could have returned, as if for your own self

You'd win the sceptre and the royalty.

Now fame no longer speaks of Telamon's

Devotion or of Theseus'. You lie here

So glorious! Those wounds, at which must I

Most marvel? Which is your blood, which your foes'?

What regiments, what massed ranks uncountable

Have laid you low? Great love himself, I'm sure,

Was jealous: you were felled by Mars' whole might.'He wept then and his tears washed that fine face

Still wet with clotting gore and his right hand

Composed it. 'Do you hate my foes thus far,

And I survive?' In frenzy he had drawn ill

His sword, stood aiming it for death. His friends

Restrained him and the king, rebuking him,

Consoled his swelling heart with words that spoke

Of fate and war's wild chances, and away

Step by step drew him from the body he loved.

So, when the colleague of his toil is lost,

A bull in numb despair leaves in mid-field

The furrow he's begun; the yoke's awry,

As one end on his drooping neck he bears

And one the ploughman shoulders, pouring tears.

So -- as it was at the beginning so it is at the end.

Polynices approaches the body of his friend and, discarding his arms, he falls *stripped* on the now drained body.

"I have squandered Tydeus," he says. "By what death shall I atone for that?"

"I've lost my other, better, brother."

What's the point to going on with this fight, asks Polynices, if Tydeus won't be there to hand me the crown?

And he thinks back to the seminal event of their relationship:

And the fine dispute of that

First night, those blows exchanged, and our brief rage,

The pledge of long affection!

"those blows exchanged, our brief rage, the pledge of long affection!"

Then Polynices says, Only Mars himself could have killed such a man as Tydeus!

He wept then and his tears washed that fine face

Still wet with clotting gore and his right hand

Composed it. 'Do you hate my foes thus far,

And I survive?' In frenzy he had drawn ill

His sword, stood aiming it for death. His friends

Restrained him and the king, rebuking him,

Consoled his swelling heart with words that spoke

Of fate and war's wild chances, and away

Step by step drew him from the body he loved.

So, when the colleague of his toil is lost,

A bull in numb despair leaves in mid-field

The furrow he's begun; the yoke's awry,

As one end on his drooping neck he bears

And one the ploughman shoulders, pouring tears.

Polynices caressed Tydeus' face with his tears and his hand;

until finally his friends lead him away "from the body he loved."

The *body* he loved.

And then, remarkably, Statius compares the love of these two men to the love of two bulls who've been yoked to the same plough.

BULLS.

Throughout the modern era we've been told that the love of male for male is a human aberration -- not seen in the natural world.

That's a LIE.

While the ancients, who lived far closer to nature than do we, knew the truth.

That bull will love bull and stallion stallion.

Do you remember what my foreign friend told us about horse trainers in his native land?

I have already mentioned that male-male bonds are considered a menace and the trainers prevent male horses from developing intimacy by not putting them together. Sex between males in horses is a well known fact (a horse breeding site also talks about this). But it is the way they are forced to bond with female horses which is more telling.

When they put the male horses for the first time with a female --- the horses react extremely negatively, even in an hostile manner. In the case I'm describing, the male horse had not eaten for a week when forced with the female. He must have been still young. I don't know if he had a male buddy before that. Then slowly he learned to adjust with the female. He had no other option, plus they trained him through rewards and punishments. And finally, he developed an intimacy with the female so much so that today he is inseparable with the female.

Isn't it how they treat humans? Does it tell us anything about human [exclusive] heterosexuality and how is it made possible? Doesn't the society use various mechanisms to psychologically keep men away from men sexually so as to keep them from forming intimacy?

Doesn't the society punish and reward men in order to train them to bond with women? And then claim that heterosexuality is natural / normal?

Yes.

Guys -- what you can see here is that the ancients didn't seek that sort of control over masculinity.

Rather, they wanted masculinity to have, as I've said in this message thread, full rein.

Which is why this poem, written by this very mainstream Roman man of letters, is so homoerotic.

The excerpts which I've cited here, don't really do it justice.

You have to read the whole book to see how common and commonplace it is for Statius to speak of men -- warriors -- erotically and homoerotically.

For example, in the battle scenes.

There's a moment when a young warrior named Atys is killed.

He's adolescent, and Statius speaks of "his smooth chest and shoulders growing still..."

It's an unmistakeable reference to the beauty of an adolescent boy.

Tydeus kills him with a spear through the groin.

And I wonder whether in the original Latin it says testicles, since wounds to the testicles were common in ancient warfare.

But even if the Latin says groin or crotch, you know -- and Statius knew -- that the men reading the poem will think "balls."

Because that's what guys do.

Atys is brought back to the palace, "bloodless but still alive, hand on his wound, neck drooping limply on his shield below, the tresses from his forehead falling back..."

Statius doesn't hesitate to describe men in erotic terms.

It's very striking.

Just as Xenophon, in his Hellenic Memoirs, refers repeatedly to the love affairs between the sons of his Spartan hosts.

That's why you need to read these books.

Because absent that you'll never know what you've really lost.

Polynices:

What regiments, what massed ranks uncountable

Have laid you low? Great love himself, I'm sure,

Was jealous: you were felled by Mars' whole might.'

Polynices is as extravagant in his grief as were Achilles and Gilgamesh.

The difference is that the death of Tydeus occurs on the battlefield and the body must be abandoned there -- because the enemy is pressing.

But even so Polynices falls naked and weeping on the body; he caresses the dead man's head; and he threatens to kill himself.

Statius did not live to write a similar scene for Achilles over Patroclus' death.

But it would have been a knock-out.

The Roman emperor Hadrian was very fond of the story of Tydeus and Polynices and the Seven Against Thebes.

A great admirer of all things Greek, the Thebaid was apparently his favorite Greek epic.

Hadrian was a fine architect and dedicated builder, and much of what we think of today as the Roman forum was his work.

But without question his greatest building was the Pantheon -- the temple to all the gods.

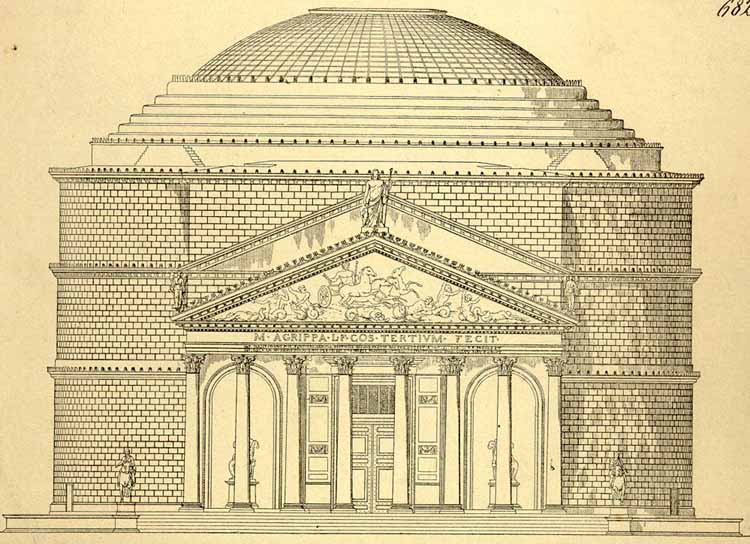

Here's a view of the Pantheon as it looks today:

And as it looked when it was designed:

And two views of its magnificent interior:

This Temple to All the Gods was the creation of a Warrior Emperor

who ardently and devotedly loved another man:

Antinous

Hadrian and Antinous did not have many years together.

While they were traveling in Egypt, Antinous died.

He drowned -- though no one knows why.

As extravagant in his grief as any ancient hero, Hadrian had Antinous deified and established temples to him throughout the empire.

And, interestingly, the Antinous cult took off and became popular.

There was something about this boy beloved by an emperor and his mysterious death which spoke to the people of the ancient world and made his worship meaningful.

But Hadrian was not consoled.

This most capable of emperors, this most exceptional of Romans, retired to his villa outside of Rome and lived the remaining eight years of his life as a recluse.

And that too is part of the Comradeship of Wounds.

Eastman:

The highest type of friendship is the relation of "brother-friend" or "life-and-death friend." This bond is between man and man, is usually formed in early youth, and can only be broken by death. It is the essence of comradeship and fraternal love, without thought of pleasure or gain, but rather for moral support and inspiration. Each is vowed to die for the other, if need be, and nothing denied the brother-friend, but neither is anything required that is not in accord with the highest conceptions of the Warrior mind.

Bill Weintraub

February 7, 2007

© All material Copyright 2007 by Bill Weintraub. All rights reserved.

Add a reply to this discussion

Back to Personal Stories

AND

Warriors Speak is presented by The Man2Man Alliance, an organization of men into Frot

To learn more about Frot, ck out What's Hot About Frot

Or visit our FAQs page.

| Heroes Site Guide | Toward a New Concept of M2M | What Sex Is |In Search of an Heroic Friend | Masculinity and Spirit |

| Jocks and Cocks | Gilgamesh | The Greeks | Hoplites! | The Warrior Bond | Nude Combat | Phallic, Masculine, Heroic | Reading |

| Heroic Homosex Home | Cockrub Warriors Home | Heroes Home | Story of Bill and Brett Home | Frot Club Home |

| Definitions | FAQs | Join Us | Contact Us | Tell Your Story |

© All material on this site Copyright 2001 - 2010 by Bill Weintraub. All rights reserved.

At the age of about eight years, if he is a boy, she turns him over to his father for more Spartan training. If a girl, she is from this time much under the guardianship of her grandmother, who is considered the most dignified protector for the maiden. Indeed, the distinctive work of both grandparents is that of acquainting the youth with the national traditions and beliefs. It is reserved for them to repeat the time-hallowed tales with dignity and authority, so as to lead him into his inheritance in the stored-up wisdom and experience the race. The old are dedicated to the service of the young, as their teachers and advisers, and the young in turn regard them with love and reverence.