i was infected needlessly

i was infected needlessly

i was infected needlessly

11-23-2003

i was infected needlessly, or, do what i say, not what i do

the following article, titled "I Was Infected Needlessly -- Risky

Behavior and HIV Increasing Among Young Gay Men" appeared in the Boston

Globe on 11/04/03.

what's interesting about it is how similar it is to an article titled With Fears Fading, More Gays Spurn Old Preventive Message, which appeared in the NY Times on 8/19/01 -- that is, more than two years ago

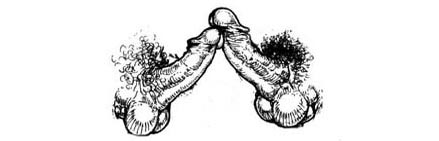

in both, a young, gay male "safer sex educator" seroconverts -- turns HIV + -- through "unprotected sex" -- that is, anal penetration

in both, the reporters, who are both women, are "respectful" of what

happened, and of course studiedly "non-judgmental"

in the NY Times story, which was reported from SF, the "safer sex

counselor," Seth Watkins, now HIV +, plans on being an example of what not to do

as does the guy in the Boston story, Nate Longtin

Nate is even going around these days saying he's "a perfect example of stupidity at work"

all too perfect i would say

guys going to a presentation by Nate Longtin will see a handsome,

healthy-looking, 20 something who got buttfucked and has lived to tell the tale

and though his message may be do what i say, not do what i did

a lot of guys will want to do exactly what he did

it's like Chuck Tarver says

using men like these as "safer-sex educators" is like hiring the guy

who failed the math exam to tutor your kids in math

the fact is that neither Seth Watkins nor Nate Longtin was capable of keeping himself free of HIV

so how is he going to be able to teach anyone else how to do it?

the answer is he can't

Nate, it would appear, is employed by none other than Fenway Community Health, the same agency whose employee, Jamie Turner, said on this board that I should be put in jail for saying that frot is HIV safe

seems to me that if anyone should be silenced -- which is what Jamie

was after -- it's Nate Longtin -- not me

cause Nate doesn't know how to stay HIV free

i do

as do most of the other men on this site

once again, if you're donating to organizations like Fenway Community Health, you should stop doing that and give the Alliance the money instead

because those "AIDS Service Organizations" are not part of the solution -- they're part of the problem

here's the article:

'I WAS INFECTED NEEDLESSLY'

Published on November 4, 2003

Author(s): Bella English, Globe Staff

Risky Behavior and HIV Increasing Among Young Gay Men

It was two weeks after Nate Longtin's checkup that the doctor called and asked him to come back to the office. Longtin was worried, but his roommate brushed it off: "She just wants to charge you for an office visit, man." But when the young man arrived for his appointment, his heart began to race and he broke out in a cold sweat. Cancer, he thought. It had to be cancer. His father had a brain tumor in his 20s, and his grandmother had recently died from cancer.

The doctor came in and sat down. "Nate, I don't have good news," she said. "You're HIV positive."

Longtin was stunned. Yes, he was gay, and yes, he'd had "unprotected" sex. "Still, it was the last thing I expected," he recalls. "I had not been promiscuous. When you're 23, you just don't think this is going to happen. You think you're invincible. It's like drinking and driving: You never think you're going to crash the car."

A generation after the AIDS epidemic cut a devastating swath through the gay community, the number of gay young men who are newly infected with the virus is alarming. Despite 20 years of warnings about "unsafe" sex-- and seeing the deadly results of the plague-- gay men between the ages of 18 and 24 do not seem to be getting the message.

The new face of HIV is not the old face. Thanks to the "drug cocktail" that can keep opportunistic infections and full-blown AIDS at bay for years, many people today with HIV are living with it, not dying from it. So the message received by a new generation of gay men is that HIV is just another sexually transmitted disease-- that, like syphilis, it's treatable, not life-threatening.

As a result, risky behavior is up. According to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, 13- to 24-year-olds made up 8.7 percent of new HIV cases in Massachusetts in 2002, compared with 6.1 percent in 1999-- an increase of more than 40 percent. And in a two-year HIV vaccine trial conducted in Boston, doctors found the rate of new infection among young males more than double what they had anticipated.

"The reasons are very complicated," says Larry Kessler, founding director of the AIDS Action Committee of Massachusetts. "It's a new generation, and they didn't witness the devastation of the '80s and the first half of the '90s. The second thing is, there are drugs now, and I think that has added to an illusion that this is not a serious disease."

It is this complacent, even cavalier attitude toward a still-deadly disease that worries those who work with gay men. Dr. Kenneth Mayer, medical research director at the Fenway Community Health Center, recently ran a study that showed substantial levels of "unprotected" sex among young gay men.

"I think what happens with a lot of young men is that they grow up with AIDS as a given, but a manageable given," says Mayer, who also directs Brown University's AIDS program. "In a country like this, where there are medicines and a high level of education, two decades into the epidemic, the numbers are very distressing."

When Longtin told his roommate he had HIV, the man responded: "Phew, I thought you were going to tell me you had cancer."

Longtin himself was not so sanguine. "It just blew me away," he says. "I had thought about [getting HIV] a few times, and fantasized that I would just run away, maybe drive my car off a cliff, Thelma-and-Louise-style."

It's not that he didn't know about the disease or how it is contracted. In bucolic Bennington, Vermont, his high school taught health education, which included sessions on HIV/AIDS. But mostly the message was about heterosexual sex and how a teen pregnancy would ruin your life, he recalls. When he came out to his parents after graduation, they were loving and supportive. "My dad said, 'Just be careful. HIV is prevalent among gay men.'"

Longtin didn't give it much thought; he hadn't yet had a sexual partner. His senior year in high school, he'd interned at a local radio station, and he took a job there upon graduation. In 2001, he moved to the Boston area and went to work at Radiocraft in Southborough, where he helped produce syndicated radio shows.

He soon settled into what he considered a serious relationship. They were together nine months but broke up in the spring of 2002. "I started going out and drinking a little more," says Longtin. He met a man at a bar. After a few dates, they had sex.

"A couple of weeks later, he stopped answering my calls," says Longtin, who is now 24. Among his friends, Longtin is known as thoughtful and careful: He doesn't cruise bars or go online looking for an anonymous hookup. "My preference is a monogamous relationship," he says.

Mayer, who has worked with HIV-positive patients for 20 years, notes that the infection rate for older gay men is also up, though not as drastically as for younger men. He recently heard a young man declare that "having HIV is like having herpes. It's just something you live with." To Mayer, such thinking is dangerous. He stresses to his patients that the drug cocktail are "a miracle" but not a cure. For the drugs to be effective, they must be taken every day, which many of his patients fail to do.

"If you're not 95 percent adherent, you are at great risk for the virus becoming resistant," he says.

Then there are the physiological complications and the longterm effects of the drugs. "We're concerned about other malignancies and liver and cardiovascular disease," he says. His message to young gay men: The epidemic "ain't over, and you can avoid this."

The message comes too late for Longtin, but not for his brethren. After his diagnosis, he decided to make another life change. He quit his job in radio and went to work for a nonprofit health-care agency. As a client advocate for JRI Health in the theater district, he works with HIV-positive and at-risk youth. He's a man on a mission: to spread the word that gay men need to disclose their status to sexual partners. Longtin's own partner failed to do so, even though he knew, according to a mutual friend. "He didn't say anything, and I didn't ask, stupidly," says Longtin.

So strongly does he feel about disclosure that he has become one of five Boston "spokesmodels" to participate in a national media campaign titled "HIV Stops With Me." At a recent kickoff at Club Cafe, the models each talked about why they've gone public with their status. Longtin told the crowd of gay men, some in business suits, some in muscle shirts, "I was infected needlessly. I don't think people should have to go through what I go through. If I can prevent one person from being infected, that's all that matters to me."

His poster, which is being displayed in gay bars and publications, bears the slogan "Rejection is better than infection." Since he looks and feels well, he believes he is a good model. "My message is: 'You can look healthy and not be.'" His other message, he adds sheepishly, is: "I'm a perfect example of stupidity at work."

To Longtin, disclosing one's HIV status to a sexual partner is a moral and ethical no-brainer. "I think it's just wrong not to," he says.

Not all gay men feel the same way. At a recent support-group meeting for young HIV-positive men at JRI, two of the men say they would not tell sex partners-- even though they had been infected by men who failed to tell them.

"You're known as a 'gift giver' if you have it," says one man. "There is definitely a stigma."

Another man, Lee-- he didn't want his last name used-- was infected by a man who lied about his status. "You get tired of telling people," he says. "If a person doesn't ask me and doesn't use protection, why should I care? People should protect themselves."

As the men say they won't disclose their status, Longtin shifts in his seat. Clearly it bothers him, but he later says he tries not to be judgmental. "I don't want to chase clients away," he says. "We're trying to reach them, discuss things, and let them come to the right conclusion on their own."

As for Longtin, it has been a year since his diagnosis, a year of not living dangerously. His new life includes taking his drug cocktail twice a day and living with the side effects: some dizziness and vivid dreams. He eats more healthfully, exercises more, no longer goes to bars alone, and is adamant that his message of disclosure gets out into the gay community. Most of all, he has disclosed his HIV status to any potential partners, and he will only practice "safe" sex.

"I choose to continue living my life," he says. He pauses. "But it's still a terminal disease." [The Boston Globe, 11/4/03]

AND

Warriors Speak is presented by The Man2Man Alliance, an organization of men into Frot

To learn more about Frot, ck out What's Hot About Frot

Or visit our FAQs page.

© All material on this site Copyright 2001 - 2010 by Bill Weintraub. All rights reserved.