Achilles on Scyros

2-7-2007

Guys

I originally posted some of this as part of the promo for The Comradeship of Wounds;

And then I realized that the issues being brought up here are too important to be lost in a promo post.

So I want to look at Statius and the story of Achilles on Scyros in more depth.

With more pix too -- so you get a better idea of how and why this story mattered to the ancients and matters to you.

Now, this article, like The Comradeship of Wounds, is in some ways a continuation of the discussion about Statius.

I know that some of you don't like dealing with a Roman poet, and/or poetry, even if it's in translation.

But there are reasons I want you to look at Statius -- and I discuss those reasons in the opening lines of The Comradeship of Wounds.

As I said in the Statius message thread, Statius was very popular in antiquity and the Middle Ages.

But he isn't much read nowadays.

The question is -- why?

Because he's a bad poet?

No -- by any reasonable standard, he's a good poet.

So if it's not his style, it has to be his content.

Let me suggest to you then that maybe the reason he's not more popular today is that he's a Masculinist.

He writes about Men.

And Warriors.

In glowing terms.

And there's no "love interest" in his work.

No heterosexual love interest, that is.

People do get married, but what drives the epic is not those marriages.

In the case of the Thebaid, it's the conflict between the two birth-brothers, Eteocles and Polynices -- and the devotion of the two brothers-of-the-heart -- Polynices and Tydeus.

Those are the guys who meet in a fight.

They get into an argument, they strip, they fight, and then they become best buddies.

Not "boyfriends" in the contemporary "gay" sense of top and bottom.

But rather -- bonded Warrior brothers.

Not the sort of thing which necessarily appeals to a heterosexualized culture.

When Statius died, he was at work on an epic life of Achilles -- the Achilleid.

There's no heterosexual love interest in that story either.

Achilles does get at least one girl pregnant, and Achilles is pissed when Agamemnon takes away a slave girl who's basically a spoil of war.

But the big love story in the Achilleid is between Achilles and Patroclus.

So in the Thebaid you have Polynices and Tydeus, and in the Achilleid, Achilles and Patroclus.

And, presumably, no one forced Statius to choose those themes.

We can assume that, like any other writer, he picked subjects which interested him and which he thought would interest his audience.

Who was his audience?

Roman men.

Establishment men.

Guys who knew how to read and had enough leisure time to read and/or listen to -- very often these poems were declaimed -- an epic poem.

And that's another reason I want you to read Statius.

I want you to experience the sort of literature that mattered to Men in a Warrior culture like Rome.

So let's take a further look at Achilles on Scyros.

Scyros was a little island with its own kingdom.

And Achilles was there because his mother didn't want him to get killed in the Trojan War.

So, when he was still a teenager, she disguised him as a girl -- effeminized him -- and hid him on the island among the king's daughters.

Achilles maintained the disguise -- but he also got chummy with one of the girls and slept with her.

In the meantime, Odysseus -- or, in Latin, Ulysses -- cleverest of all the Greeks, had been sent on a mission to find Achilles and get him to the war.

So -- Ulysses and a buddy visited the island where Achilles was hiding out, and used a ruse.

They said they had brought gifts for all the girls.

Which they set out on a table.

But among the gifts were some instruments of war.

Here's what happened, as Statius tells it in the Achilleid -- the wonderfully colloquial translation is by David Slavitt:

[The girls] gather around the hall table where presents

The girls, being girls, are attracted

But the bold Achilles, Peleus' son, of Aeacus' line,

His eyes are ablaze and his hair is electric, an animal's hackles. ..

So -- his mother, in seeking to protect him from the war, has effeminized him by dressing him in girls' clothes and telling him to act like a girl.

And he goes along with the charade.

But when Ulysses arrives with the weapons, he's immediately recalled to his true, MANLY, MASCULINE, self.

The battle scenes on the shield "speak to his spirit."

"He lifts the shield and the spear beside it, hefts them, wields them,

Because he has the soul of a warrior.

He lets out a battlecry "that rings out from the stonework."

Ulysses speaks to him, "one man to another":

"We know who you are. But more important, you know."

Right -- we, your fellow Men and fellow Warriors, know who you are, but more important, YOU KNOW WHO YOU ARE.

And then Ulysses removes the effeminizing disguise from Achilles, and, as another warrior blows a piercing, martial, blast, on a war trumpet,

"Achilles, strange to believe,

The growing taller and broader of course is a metaphor for erection.

And this is something which the pyschoanalysts used to call "masculine inflation" -- that is, the male "inflated" by his masculine pride.

Not exactly the sort of stuff you'd see on Lifetime.

The point is that when Achilles is re-called to his *AGGRESSIVE*, Masculine self, he becomes a MAN.

And this accords with my own life experience.

My initial session -- just one session -- of training in karate changed me.

It was literally a life-changing event.

By learning how to use my body as a weapon, I was restored to my manliness.

And I changed.

I became visibly and by a large order of magnitude more self-confident.

Friends and strangers both noticed the difference, and commented on how "cocky" -- I heard that word more than once -- and confident I was.

So: Statius is a Masculinist writer, and he's very positive about Men and Manliness.

He thinks fighting is good for you.

He's not in favor of war by the way.

He recognizes the horrors of war.

But he clearly thinks that fighting is natural to and is good for -- MEN.

He also thinks that "present rage" may foretoken "future love."

Between MEN.

That's why I want you to make the effort to read him.

Like Achilles, you owe it to YOUR SELF -- to do that.

Now -- here are some pix.

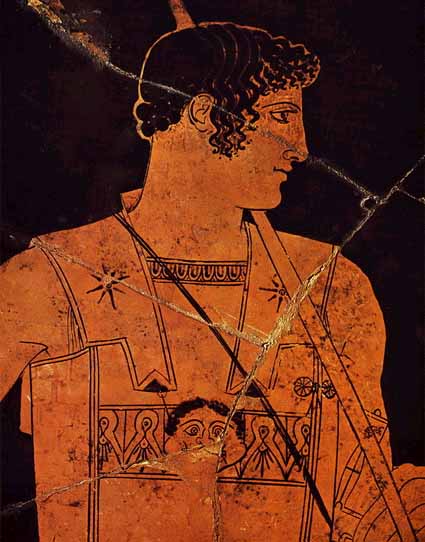

This is a Roman mosaic of Achilles at the moment on Scyros when he grabs the weapons and drops the charade:

are out on display. Diomedes invites them to choose what they will.

They look to the king who is pleased and nods in assent -- he cannot

suppose that the gifts of Greeks are not always what they may seem.

He has, in any event, no cause to suspect Ulysses,

famed though he is for his guile.

to the little drums and ritual cymbals, or pretty headbands

set with precious stones. To the weapons they pay no mind,

or else they assume these are gifts for Lycomedes himself.

is dazzled. His eyes shine at the sheen of the gold on that shield.

The wonderful workmanship invites him. The battle scenes

on the boss and around the rim speak to his spirit. He lifts

the shield and the spear beside it, hefts them, wields them,

wears them

as the soul wears its flesh. He forgets his mother's instructions

and [his girl friend's] hints. He plants his feet like a soldier

and tries one battle cry that rings out from the stonework.

Think of a lion cub that some hunter has reared and tamed,

a regular pussycat, but then one day, when it sees

the steel of the javelin's tip, something deep in its heart

rebels. The beast reverts, goes wild, ashamed to have fawned

and purred and played like a pet. It turns on its keeper and mauls him.

The room is hushed. They are all staring. Achilles puts down

the shield, but he sees in the metal his own reflection -- a face

noble and warlike, but wearing a woman's headband and earrings.

He is thrilled and he blushes in shame. He cannot move. Ulysses

already beside him is speaking calmly, one man to another:

"We know who you are. But more important, you know.

The game is over. The ship is waiting. The moment is here.

The towering walls of Troy invite you. At every step

you take in their direction, they tremble. You did as your mother

instructed, but now it's over." Ulysses removes the headband

from Achilles' head and looks to Agyrtes, who takes the trumpet

from the folds of his cloak and blows it, a piercing martial blast

that scatters the terrified girls. But Achilles, strange to believe,

grows taller, broader. ..Amazing! He towers over Ulysses.

That spear in his huge hand now seems like a mere toy

as he waits, poised, ready for Hector or anyone else.

wears them as the soul wears its flesh."

grows taller, broader. ..Amazing! He towers over Ulysses.

That spear in his huge hand now seems like a mere toy

as he waits, poised, ready for Hector or anyone else."

You can see Achilles grasping his shield and spear, with his girlfriend to our left trying to stop him and Ulysses to our right no doubt pleased with the success of his plan.

And you can see that Achilles' skin is lighter in tone than that of Ulysses -- because, as we discussed in the post titled Heterosexism's encroachment on masculinity, Achilles' hanging with the women has effeminized him -- which in terms of Roman artistic convention, means that his skin will become lighter and his musculature softer.

But, as we can see in the mosaic, having been recalled to his true Masculine self, his body posture is that of the defiant warrior.

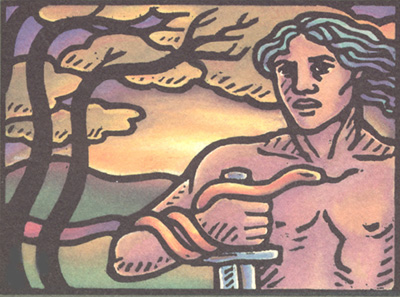

So this was a popular theme in Greek and Roman art -- the Warrior recalled to himself.

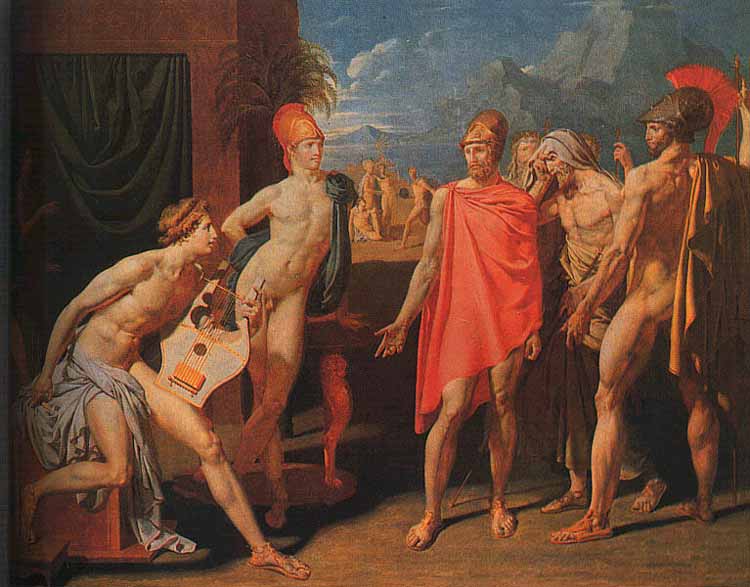

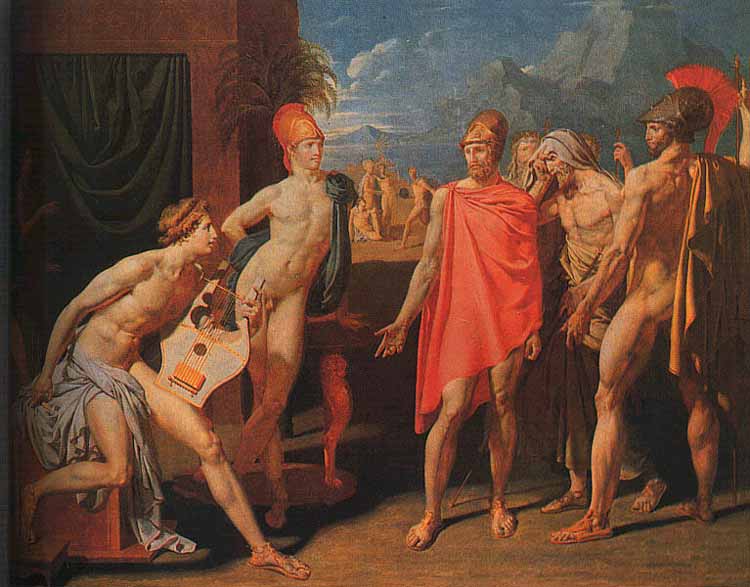

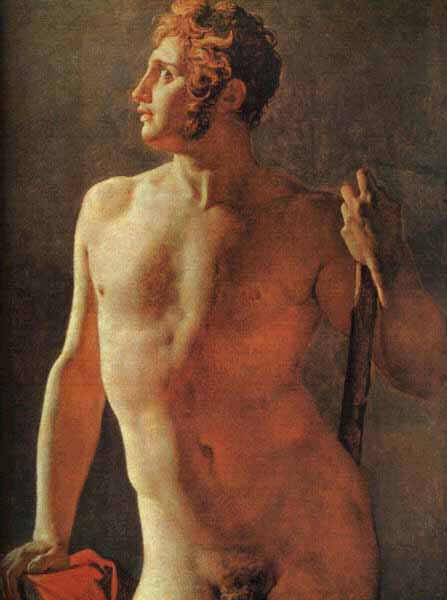

In this next pic, which is by the 19th-century artist Ingres, Achilles is at Troy, but has withdrawn from the fighting; and a delegation of Greek soldiers comes to implore him to return to battle.

The Ambassadors of Agamemnon in the Tent of Achilles

The ambassadors are to the right.

Achilles is on the left, playing the lyre, which of course he learned from his boyhood sojourn with the centaur Chiron -- see The Comradeship of Wounds for more about that;

and his playing the lyre reminds us that in most Warrior cultures, the Warrior could and did have a so-called sensitive side.

Standing next to Achilles is Patroclus:

So you have a sense of Achilles and Patroclus hanging out nude together in their encampment at Troy.

Of course this is a 19th-century artist's painting, but his conception of the Greeks is correct.

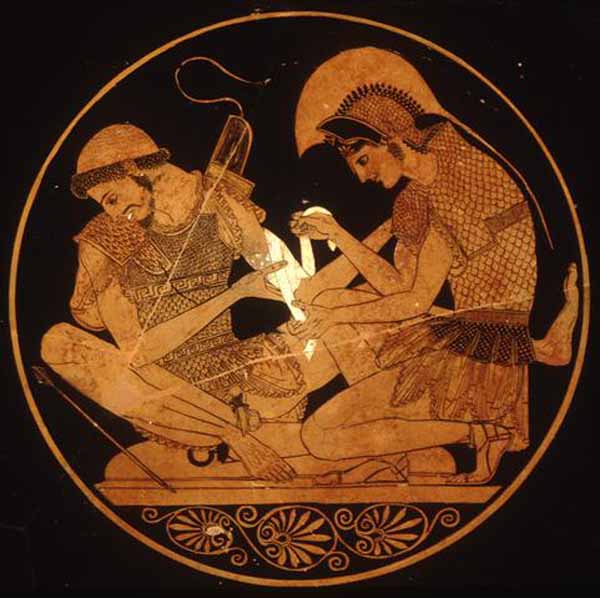

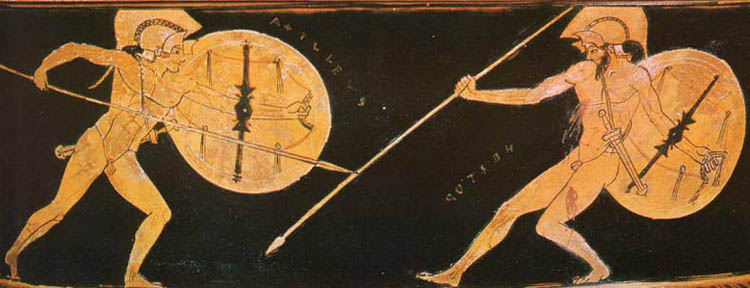

Because here we have a Greek vase painting of Achilles and Patroclus, and the genitals of both men are visible, in the case of Achilles, who's to the right, through his diaphanous kilt.

So the artist has gone to some trouble to make sure that the genitals of both men are visible.

Of course nudity was not just for the encampment.

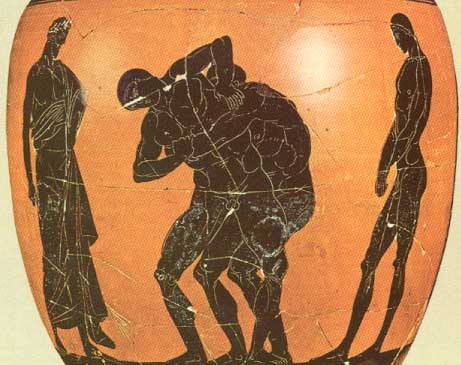

Or everyday activities like wrestling:

Nudity was also for combat:

So we can see that nudity really matters in this culture, and that men being naked in the presence of other men and particularly when fighting other men was crucial to their concept of who they were as Men and as Warriors.

Finally there's this statue of Achilles -- or perhaps Diomedes -- there's some debate; but again, this is an idealized warrior image:

And again he's nude.

So in this culture, which is by and large homosocial, male nudity really matters and is the norm not just in private but in public scenes as well.

In our culture, by contrast, it's only in pornographic images that men can be nude.

Otherwise, the genitals are always hidden.

This is a famous statue of Achilles which was erected in Hyde Park as a memorial to Wellington in the early 19th century:

And it's bizarre.

Though of course commonplace for this sort of public sculpture in our culture.

What you have is an image of immense male power, with a fig leaf over the genitals -- they're hidden.

Which has the effect, in this tribute to a military hero, of divorcing the male not just from his sexuality but from the source of his aggression and his aggressive power.

That makes no sense.

And in this painting by Ingres,

the painting ends at the pubic bush.

It's disquieting.

It's almost as though the figure has been castrated.

And it sends a message denigrating male sexuality, and sexuality in general.

Which the Greeks didn't do:

There's a big difference, and it has a profound effect on how we think about Men, about sexuality, and about male sexuality.

Greco-Roman culture exalted and celebrated Masculinity.

And Manhood.

And though Roman art doesn't abound in the images of male courtship and love which are so prominent in Greek vase paintings, I have no question that such love was respected so long as it was Manly.

Being a Man -- Vir -- and Manliness -- Virilis -- and Manly Valor or Virtue -- Virtus -- are what mattered to the Romans.

Virtus = Virtue = Valor.

Valor is Virtuous.

Which is why Hadrian could retain the respect of the public and his peers while being involved with Antinous.

And why too he could institute an Antinous cult after the youth's death.

It's the quality of the relationship which mattered.

And that's what the Sioux-warrior-turned-American-physician Charles Eastman said as we quote him in THE COMRADESHIP OF WOUNDS:

The highest type of friendship is the relation of "brother-friend" or "life-and-death friend." This bond is between man and man, is usually formed in early youth, and can only be broken by death. It is the essence of comradeship and fraternal love, without thought of pleasure or gain, but rather for moral support and inspiration. Each is vowed to die for the other, if need be, and nothing denied the brother-friend, but neither is anything required that is not in accord with the highest conceptions of the Warrior mind.

Bill Weintraub

© All material Copyright 2007 by Bill Weintraub. All rights reserved.

Add a reply to this discussion

AND

HEROES is presented by The Man2Man Alliance, an organization of men into Frot

To learn more about Frot, ck out What's Hot About Frot

Or visit our FAQs page.

| Heroes Site Guide | Toward a New Concept of M2M | What Sex Is |In Search of an Heroic Friend | Masculinity and Spirit |

| Jocks and Cocks | Gilgamesh | The Greeks | Hoplites! | The Warrior Bond | Nude Combat | Phallic, Masculine, Heroic | Reading |

| Heroic Homosex Home | Cockrub Warriors Home | Heroes Home | Story of Bill and Brett Home | Frot Club Home |

| Definitions | FAQs | Join Us | Contact Us | Tell Your Story |

© All material on this site Copyright 2001 - 2011 by Bill Weintraub. All rights reserved.