And now a few words from Publius Papinius Statius

And now a few words from Publius Papinius Statius

1-31-2007

Over the last couple weeks, there's been a fair amount of news -- which I hope to be getting to soon -- that's depressing for those who believe in Masculinity and the True Love of Man for Man.

That being the case, I think it's time for a few words from Publius Papinius Statius.

Publius Papinius Statius -- commonly known as Statius -- was a Roman poet who died in 96 AD.

But dude -- don't the let the words "Roman poet" deter you from reading the rest of this post.

Because if you do, you'll miss some of the hottest writing about MEN -- on the planet.

Statius was a fairly typical man of letters of his age.

He wrote a number of poems -- many of which are very fine.

But his greatest work was his retelling of a Greek myth -- "Seven Against Thebes."

In Seven Against Thebes, two brothers, Eteocles and Polynices, have a falling out over who will rule the Greek city of Thebes.

Eteocles exiles Polynices, who goes to the city of Argos and persuades its king to invade Thebes and restore him to the throne.

Thebes is a city with seven gates, and Polynices -- his name means "much strife" -- recruits seven heroes to battle at each of those gates.

And battle they do.

The story is bloody and violent, and in the end Polynices and Eteocles succeed only in killing each other.

Seven Against Thebes is an epic story.

And to retell it, Statius wrote an epic poem -- the Thebaid.

The Thebaid, which was very popular throughout antiquity and the Middle Ages, isn't much read today.

But it's a dynamite work, and more to our point, it's incredibly homoerotic.

Not that there's any homosex in the book.

There isn't.

There's no heterosex either.

Instead, Statius creates a sustained and indeed unrelenting homoerotic tension which permeates the poem.

Why?

Why homoeroticism?

Because Seven Against Thebes -- the Thebaid -- is a story of male-male conflict and aggression -- carried to the max.

And I do mean to the max.

These guys strip and fight naked at the least provocation.

And in those naked fights they go for maximum and mutual destruction.

There's blood and gore everywhere.

Towards the end one of the heroes literally eats the still-warm brains out of the head of his dead enemy.

It's intense.

And, as you'll see, it's erotic.

Statius clearly understood the aggressive underpinnings of male-male eroticism.

Or, if you prefer, the homoeroticism underpinning male-male aggression.

They're two sides of the same coin.

Which is why attempts to find cures for "homosexuality" will always fail.

Because male-male sexuality -- man2man -- is part of being a Man.

You can't divorce homosexuality, as we call it, from sexuality in general, and you can't divorce it from aggression.

And if you deprive the male of his sexuality and his aggression -- you no longer have a Man.

You have a eunuch -- at best.

So it's like Redd says: We're all homo sexual because we're all homo sapiens.

Here are a couple excerpts from the poem.

The translator is A. D. Melville; his translation is out of print, but you can find the book used, and there are a couple other translations out there as well.

In this first excerpt, the heroes Polynices and Tydeus meet in a fight.

They're both exiles, they're homeless, they're road-weary, and they come to blows over a place to sleep:

Here on them both the wheel of fortune brought

First a brief pause for threatening words, then rage

Taller and towering stood the prince of Thebes,

Then, as they battle, blow on blow is struck

"frenzy and bloodshed"

"stood stripped to fight"

"knees are flexed to bruise soft sides and loins"

"hot with men's raw sweat"

See what I mean?

And Statius is just getting started -- that's in Book I and there are twelve books.

Notice also that Tydeus, who's one of the greatest and most brutal of the Greek heroes, is described as having a "tiny frame."

That's based on the Iliad, which was written perhaps nine hundred years earlier.

In the Iliad, the goddess Athena approaches Tydeus' son Diomedes, and says

Tydeus got him a son who is little enough like him,

[Iliad, v 801]

Athena then persuades Diomedes to attack the war god Ares, who is, as it happens, his great-grandfather.

Diomedes, in other words, is a chip off the old block, and size doesn't matter.

The Greeks knew that it wasn't the dog in the fight, it was the fight in the dog.

Let's get back to Tydeus and Polynices, who are naked, bloody, and ardently kneeing groins while trying to gouge each other's eyes out.

They're interrupted in those endeavors by the king of Argos, who having come upon "a sight

'Come now, have done with menaces that night

So: the king says, "Your present rage perhaps

And that's exactly right.

I've often spoken of the true, manly, male bond being a passage through rage to love.

That's what happens here.

The king realizes that the coming of these men fulfills a prophecy about who will marry his two daughters.

He immediately prepares a feast; gets the guys clean and comfortable -- "Placed apart the two

-- and brings in his daughters -- who he then gives them in marriage.

Now Polynices and Tydeus are related through marriage, and these brothers-in-law become true brothers of the heart and inseparable companions, as we see a few pages later:

[Polynices] hurried from the well-loved room to speak

"sharing each battle in his faithful heart,

The implication is inescapable: the love that binds them is strong because they fought.

Or, as the king says, rage -- not anger, but rage expressed in physical and brutal male aggression -- foretokens Love.

The Greeks understood this well -- that for the male, sex and aggression are linked.

Now, let me be clear about this:

"A passage through rage to love" does NOT mean that every time two guys fight they fall in love with each other.

That's not true in the UFC, though those fights often end with a hug; and it's certainly not true for warriors, who usually are trying to kill each other.

But on occasion, in what is for these men a one-time and life-changing event, love does follow strife.

So: "A passage through rage to love" refers to what is usually for the Greeks and other warrior peoples like the Celts a SINGULAR event.

Something which happens once in a lifetime, usually in the ardor and impulsiveness of youth, and which results in an eternal warrior bond between the two men.

Frenzy and bloodshed; neither would endure

to share a roof to ward the night away.

Swelled as taunts flew, and both sprang to their feet

And bared their bodies and stood stripped to fight.

Proud in his prime, but soul and strength no less

Supported Tydeus; in his tiny frame

Through every limb a greater valour reigned.

On face and forehead, thick as arrows fall

Or Arctic hail, and knees are flexed to bruise

Soft sides and loins. Like, when the years bring on

Jove's contests at Olympia and the dust

Is hot with men's raw sweat and, seated round,

Crowds urge the young lads on with rival cries,

And mothers wait outside to hail the prize,

So those two charged, fired by no love of fame --

Hate was the spur -- and deep into each face

The fingers scratch and probe and penetrate

Their flinching eyes.

since Tydeus was a small man for stature, but he was a fighter ...

keeping that heart of strength that was always within him ...

Of terror, faces torn, cheeks bruised and smashed,

Streaming with blood," determines to make peace between them:

Or sudden wrath or valour prompted. Pass

Beneath my roof. Shake hands to prove your hearts.

There's meaning in this business and the gods

Are not aloof. Your present rage perhaps

Foretokens future love, a memory

To warm your hearts.' Nor were the old man's words

A vain presage. This comradeship of wounds

Issued in such fine trust as Theseus had

Who shared high risks with fierce Pirithous,

Or Pylades who, when Orestes' mind

Was gone, preserved him from the Fury's rage.

So then the turmoil in their hearts was soothed

By the king's words, as when the ocean's deeps

That winds have made their battleground subside,

Yet still in drooping sails one lingering breath

Is long to die, and both with a good grace

And hearts at ease entered the royal abode.

Foretokens future love, a memory

To warm your hearts."

Young men recline, their wounds now washed and dry.

Each sees the bruises on the other's cheeks

And each in turn forgives";

Sadly to Tydeus, now his partner, now

Sharing each battle in his faithful heart,

So strong the love that bound them since they fought...

So strong the love that bound them since they fought"

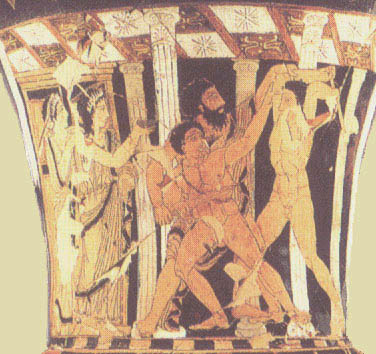

The Fight

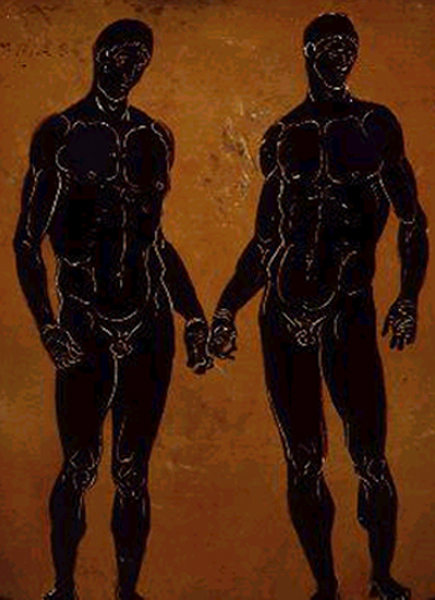

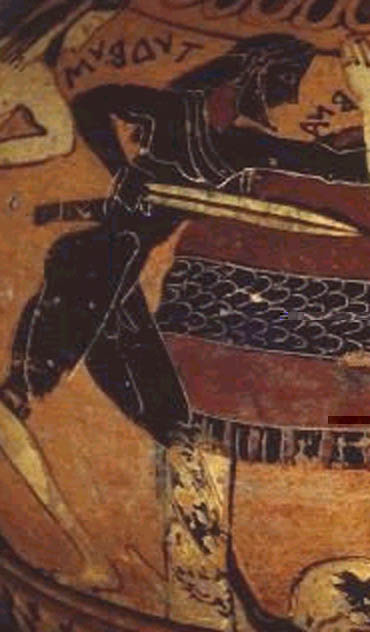

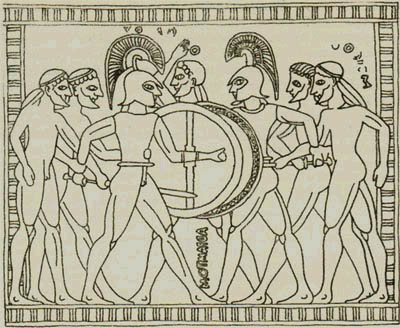

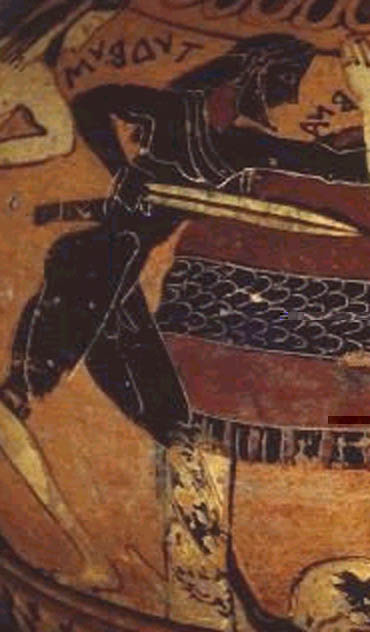

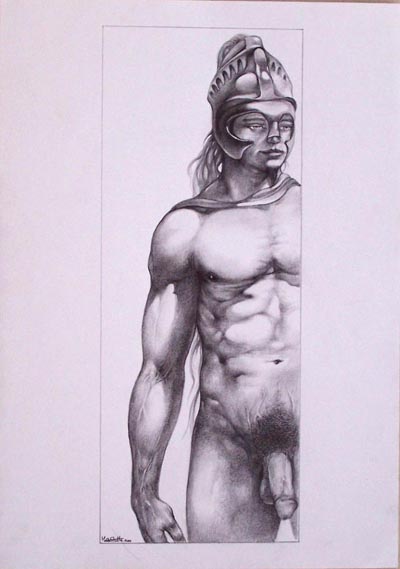

Polynices on the right, Tydeus to the left, and the King in the center

There are many warrior pairs like this in Greek myth.

As Statius says, "This comradeship of wounds

Issued in such fine trust as Theseus had

Who shared high risks with fierce Pirithous,

Or Pylades who, when Orestes' mind

Was gone, preserved him from the Fury's rage."

Theseus and Pirithous

Orestes and Pylades -- who we talked about in The Dutch Experiment.

Achilles and Patroclus

These were powerful examples for the Greeks -- and the Romans -- of the warrior bond.

Now, a number of chapters later, the Argive warriors are holding games.

And they get to the boxing:

Monstrous to see and striking monstrous fear

Capaneus stood forth and bound on hands and

Straps of raw oxhide, black with studs of lead,

Himself no softer. 'Give me one', he roared,

'Of all these thousands! Would my rival were

A Theban I could rightly do to death,

And not stain my fine strength with Argive blood!'

They stood aghast and terror kept them dumb.At length from Sparta's naked ranks there sprang

Alcidamas, to their surprise, and made

The Dorian princes marvel, but his friends

Knew he'd grown up in Pollux' boxing-ring

And trusted in his trainer. Hands and arms

Pollux himself had guided -- limbs he loved! --

And sparring with him many a time admired

His matching fury and, exultant, snatched

Him up and pressed him naked to his chest.

So: the Spartans are naked -- as they would have been -- and from among them comes Alcidamas to answer the challenge.

Alcidamas has been trained by Pollux -- whom the Greeks called Polydeuces -- and was loved by him:

"many a time admired

His matching fury and, exultant, snatched

Him up and pressed him naked to his chest."

"matching fury" is what turns Pollux on.

He exults in it.

To the point of giving his student a big, hard, naked, hug.

The implication of course is that Pollux and Alcidamas were lovers.

What follows in the poem is an account of the sort of boxing which Statius and his readers would have seen at athletic competitions -- not gladiatorial games but true athletic competitions between free men -- in Rome:

Capaneus disdained his challenge, mocking him

As if he pitied him, and laughing called

For someone else, but forced at last to fight,

Faced him and anger braced his bulging neck.

Poised on tip-toe at their full height they raised

Hands thunder-charged, their faces safely tucked

In sheltering shoulders, watching all the while,

No way for wounds left open. Capaneus

Stood fierce and huge with his enormous frame

And far-flung length of limb, as though from Hell

The giant Tityos should rise, if the grim birds

Granted him leave. The other, still a lad,

Had yet matured in strength beyond his years.

His youth's fine spirit promised a great prime;

None wished to see him lose -- cruel bloody sight! --

And with a heartfelt prayer all feared the fight.Each measured up the other, hoping for

An opening; no blows yet in anger struck.

Fear for a while was mutual, caution still

Mingled with fury as they lightly sparred,

Glove rubbing against glove, the bright sheen dulled,

Both of them testing. Better trained, the lad

Postponed his onslaught and reserved his strength,

Fearing what lay ahead. But Capaneus,

Squandering, reckless, hurled himself, both hands

Flailing, teeth vainly grinding, towering up

To his own damage. But with skilled foresight

And all his country's clever vigilance

The Spartan dodged and parried, safe and sound

By ducking swiftly or deflecting each

Assault, feet pressing forward, face held back.And often too he met the unfairness of

His rival's strength -- such practised skill he had,

Such stalwart talent --- by a daring dart

Under his guard and then leapt up and loomed

High over him. As leaping breakers dash

Against a threatening rock-face and fall back

Broken, so he wheeled round his furious foe

Battling. He kept his leading arm outstretched

To threaten eyes and ribs, and tricking thus

His rival's guard implanted cunningly

A sudden hit, a wound that marked his brow.

Blood drawn! Across his temples a warm line!

Not yet aware, a sudden rolling cheer

Bewildered him, but when he chanced to wipe

His face with his tired hand and saw the red

Stripe on his glove, no lion raged so wild

Or tigress wounded by a hunter's spear.

He drove the young lad right across the field,

Gnashing his teeth in ghastly fury, till

The lad was toppling, almost on his back,

As whirling hands struck time on time. The blows

Were wasted on the wind or fell on gloves.

The Spartan, moving nimbly, warded off

A thousand deaths that showered on his head,

And swift feet helped, but he, his skill recalled,

Fought as he fled and fleeing still struck back.Now both of them are panting and distressed;

Pursuit is slower, flight is not so swift;

Knees fail the two of them, both stop and rest.

So roaming sailors worn by long sea-Ianes

Welcome the signal given from the poop

And rest their oars awhile; but rest scarce theirs

When to the oars they're summoned once again.A second frenzied rush! But he got clear

And, crouching, charged himself and Capaneus

Pitched on his head and as he rose the lad

Dealt him a wicked blow again and stood

Pale-cheeked to see his handiwork so good.The Argives shouted; never shores or forests

Gave such a roar. But when Adrastus saw him

Struggling to rise, shaking his fists, intent

On deeds insufferable, 'Quick', he cried,

'Quick, friends, he's mad. I beg you, hold him back

And bring the palm and prize. He'll never stop

Till the lad's skull is crushed into his brain.

Rescue the poor doomed Spartan!' In a trice

Tydeus sprang forward and Hippomedon

Answered his call. Those two with all their strength

Hardly restraining those two hands of his,

Pleaded, 'Stand back! You've won! It's a fine thing

To grant life to the loser. This lad too

Is one of ours, our comrade in the war.'

No bending that great prince! He thrust away

The palm and breastplate offered him and roared,

'Hands off in clotted grime and gore I'll crush

Those girlish cheeks with which he charms so well.

I'll send his body shapeless to the tomb

And give his Spartan trainer cause to mourn.'

He swelled with rage and claimed he hadn't won,

But his friends forced him back and, countering,

The Spartans praised their splendid son with cheers

And mocked those menaces with long loud jeers.

|

MAN to the max.

"A sudden hit, a wound that marked his brow.

Blood drawn! Across his temples a warm line!

Not yet aware, a sudden rolling cheer"

The first blood brings a roar from the crowd.

And the naked Spartans are indifferent to the loser's jibe about their champion's "girlish cheeks with which he charms so well."

They respond with cheers for Alcidamas and jeers for the sore loser.

The Spartans know what the relationship between Alcidamas and Pollux was about.

Because they've all been there.

And they know there's nothing "girlish" about it.

That's the point.

Alcadamus, like Pollux, is a masculine man who exults in the naked fury of the fight.

Now, Statius is not going to just leave us with brutal, bloody, naked boxing.

He follows it with brutal, knee to the groin, naked wrestling, the combatant bodies coated with oil, sand, and hot raw sweat:

Long since had great-souled Tydeus felt the goads

Of others' honours and his own high worth.

Well did he run, well hurl the discus too,

And no less skilled in boxing, but his heart

Set wrestling far above all other sports.

So when the call of fame fired young men's hearts

To wrestle, Tydeus doffed his awesome cloak,

The boarskin of his homeland. Challenging,

Agylleus reared his height, boasting descent

From Hercules, of Herculean bulk,

So tall huge shoulders towered, so monstrously

Beyond all human measure, but he lacked

His father's steely strength. Those limbs of his

Were fat and flabby, drifting loose and limp.Hence Tydeus' daring confidence to beat

That great opponent. Though he looked so small,

His bones were massive and his arm-muscles

No easy matter. Never in frame so slight

Has nature dared enfold such fiery might.

Their bodies glad with oil, they both made for

The middle of the ring, then dried damp limbs

With sand, alternate handfuls, robes of dust,

And hunched their heads and held their cunning arms

Outstretched. Tydeus, crouching, his knees almost

Touching the sand, with clever skill made tall

Agylleus stoop to his own height, but he

As a huge cypress, queen of Alpine peaks,

Bows to the wild south wind, roots scarce secure,

And nears the ground but soon will rise again

Skywards, so towering Agylleus bent

Over his little foe. Then both in turn

Clutched at necks, flanks, chests, shoulders, foreheads,

Eluding legs. At times they hung there locked

In a long clinch, then broke the fingers' grasp,

As savage as the leaders of the herd,

Two bulls in ghastly battle. In the meads

Stands the white heifer waiting for the winner,

While chests are torn in frenzied clash and love

Applies his goads and heals the wounds' sharp pain.

So boars will fight with lightning tusks, so bears

With ugly clutches wage their furry feuds.

Tydeus still kept his strength, his limbs untired

By heat or dust; on muscles trained for toil

His skin was taut. Agylleus, far from fit,

Gasped in distress and panted heavily,

And as the sweat washed off his coat of sand,

Grasped the ground furtively to find support.

Tydeus pressed his attack and feinting at

His neck grasped for his legs, but failed the attempt,

His arms too short, and down upon him came

Towering Agylleus, crushing, burying him

Beneath that giant fall. So in the hills

Of Spain a miner, leaving far behind

The world and the bright daylight, if the earth

That hangs above him trembles and the root

Falls with a sudden roar, lies crushed inside

The rockfall and his corpse has not restored

His angry spirit to its own bright stars.

But Tydeus all the fiercer, gallant heart

Still high above, slipped straightway from the clutch

Of that unequal weight and circled him

As he stood wavering and suddenly

Clung to Agylleus' back and grappled flank

And groin in a swift clinch and clamped his knees

Between his legs, then as he tried to insert

His hand and foil the hold -- such impudence --

Lifted him high, a load most marvellous,

Most terrible. So Hercules, fame tells,

Once held Antaeus sweating in his clutch

When he had found the trick, and no hope then

Of falling, never toe allowed to touch

His mother earth. A roar went up; the ranks

Cheered in delight. Then, poising him aloft,

He loosed him suddenly and let him fall;

Sideways and followed up, hands fastening

On neck, and legs round groin. Beleaguered thus

Agylleus failed and only shame fought on.

At last he sprawled, belly and chest prostrate,

And then, a long while later, sadly rose,

Leaving his shameful imprints in the soil.

But Tydeus with the palm in his right hand,

The prize of shining weapons in his left:

'What if I'd not lost blood in Dirce's'land,

Blood shed in no small measure, as you know,

Where these scars proved just now the troth of Thebes!

Displaying them, he gave his friends his proud

Prizes and for Agylleus came his due,

A breastplate unremarked as he withdrew.

The battle is primal, and primally male.

The athlete-warriors are compared to bulls, boars, and furrily-feuding bears.

Tydeus -- did I mention that his name means "Thumper"? -- has a fierce and gallant heart.

But he also knows the importance of grappling the groin -- what Naked Wrestler calls the Man area.

And that's how Tydeus wins, "hands fastening

On neck, and legs round groin."

While there's a lesson here for boys who might be small in stature:

"Never in frame so slight

Has nature dared enfold such fiery might."

And so it goes: the Thebiad is an unrelenting exercise in unrestrained masculinity.

What the Romans called "virtus" -- Valor.

As was so much of the ancient world.

Now -- I said that in the Iliad, Tydeus' son Diomedes battles his great-grandfather Ares.

I know that's confusing, so here's the way it works from father to son:

Ares --> Oeneus --> Tydeus --> Diomedes

Ares was the Greek god of war -- as one website puts it, he "was the great Olympian god of war, battlelust and manliness."

ARES: GOD OF COURAGE and MANLINESS

I) GOD OF COURAGE & MANLINESS, STRENGTH & ENDURANCE

II) PERSONIFICATION OF WARLIKE-SPIRIT, MANLINESS

Warriors were called henchmen or scions of Ares, and the foremost heroes were often compared favourably with the god.

War, battlelust, and manliness.

That's the Thebiad.

Now, let me make clear that though Statius' telling of this story is intensely homoerotic, he didn't invent that homoeroticism.

It's inherent in the story, which is why it was so popular.

Interestingly, Seven Against Thebes in the original Greek epic version, which so far as I can tell is no longer extant, was a favorite of the Roman Emperor Hadrian, who ruled from 117 to 138 AD.

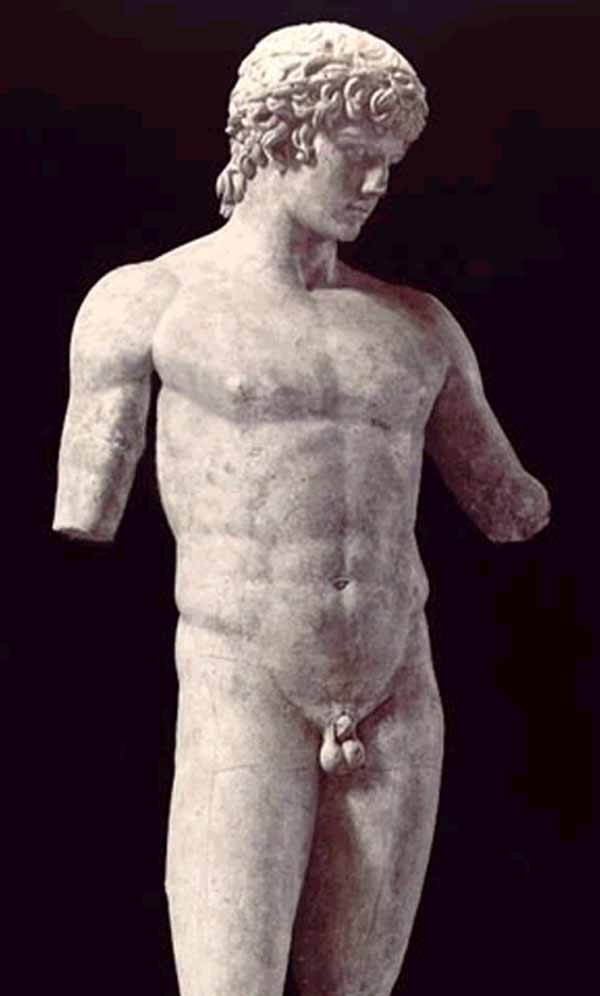

Hadrian is generally considered one of the most exceptional people produced by Rome: in addition to arguably having been the best and most capable emperor, he had an extensive military career; he was a champion of Greek culture; a poet in his own right; a brilliant architect -- he gave the world the Pantheon; and he had a very ardent and very public relationship with a Greek youth -- Antinous.

But we need to understand that though Hadrian was very public about it, he wasn't unusual in his love for another man.

Every Roman emperor from Caesar forward to Commodus, with the single exception of Claudius, had "boyfriends."

And five of those men -- the adoptive emperors Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius -- gave Rome the best and most sustained period of good government she ever had.

So the homoeroticism of the Thebiad was both inherent in the story -- and of course in Greco-Roman culture.

When Statius died, he was at work on another epic: the Achilleid, a re-telling of the life of Achilles from boyhood forward.

He was only able to write a couple chapters before he died.

Would that he'd had the chance to complete it.

The scenes between Achilles and Patroclus would have been dynamite.

Because he sure understood men, rage, sex, aggression, and man2man.

Like I said, Statius was a fairly typical Roman man of letters.

He was married, and it would appear happily so.

But he also understood the bonds -- those sacred bonds formed in adversity and strife -- between Men.

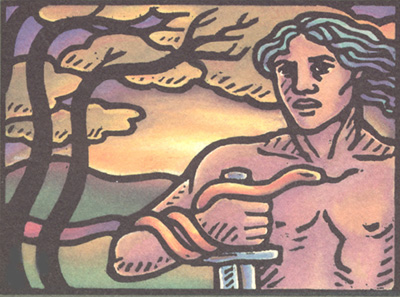

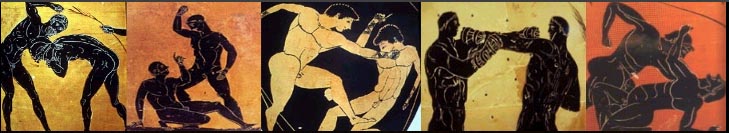

Ares -- god of war, battlelust, and manliness

Ares' grandson Tydeus

Greek Warriors ca 550 BC

Greek Warrior Boxers ca 430 BC

American Warrior Pankratiasts ca 2007 AD

Bill Weintraub

© All material Copyright 2007 by Bill Weintraub. All rights reserved.

Re: And now a few words from Publius Papinius Statius

2-10-2007

There are three follow-up articles to this one.

The Comradeship of Wounds; and

They're lavishly illustrated, and I strongly recommend that you read them all.

Years ago, in his post What It Means To Be a Man, Bill G said

Everything I've always felt, and the ideas I never thought others shared are expressed here.

The great ideals of the Homeric world and the thoughts of what it means to be a man...

That's a great summary of what we're about.

"the ideas I never thought others shared" -- we do share these ideas;

"the great ideals of the Homeric world" -- and we share those ideals

Those ideals are alive in the work of someone like Statius.

They're alive in the words of someone like Charles Eastman.

And they're alive in my heart -- and I hope in many of yours.

But they're not common in our culture.

Which means that you really benefit from experiencing those ideals on this site.

I say in The Comradeship of Wounds that "being determines consciousness."

Which is true.

Speaking for myself, when I read someone like Statius, I'm lifted up.

When I watch TV, I'm cast down.

So when I put together pages like these, they're basically my gift to you my fellow Warriors.

I hope you'll read them, and take the lessons there offered to heart.

Bill Weintraub

February 10, 2007

© All material Copyright 2007 by Bill Weintraub. All rights reserved.

|

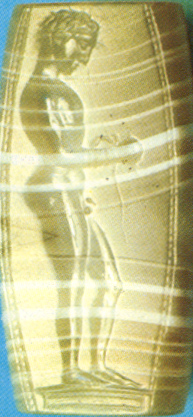

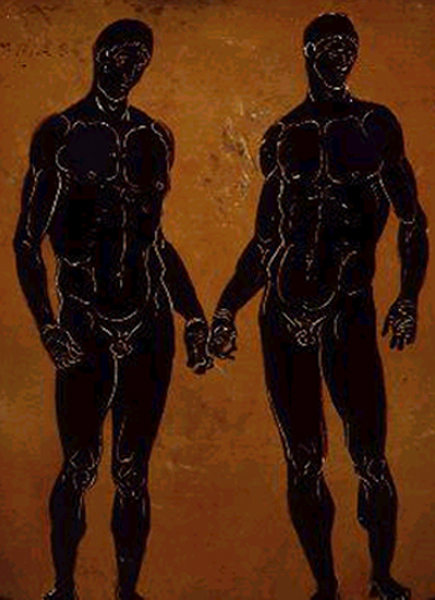

The Greek hero Tydeus.

Tydeus is a great and formidable fighter.

Notice the prominence of the genitals, and in particular the ball sack.

The Greeks were very clear about the relationship between sex and aggression.

And between aggression, honor, and virtue.

What the Romans later conceptualized as

Vir -- Virilis -- Virtus: Man -- Manliness -- Manly Virtue

Add a reply to this discussion

AND

HEROES is presented by The Man2Man Alliance, an organization of men into Frot

To learn more about Frot, ck out What's Hot About Frot

Or visit our FAQs page.

| Heroes Site Guide | Toward a New Concept of M2M | What Sex Is |In Search of an Heroic Friend | Masculinity and Spirit |

| Jocks and Cocks | Gilgamesh | The Greeks | Hoplites! | The Warrior Bond | Nude Combat | Phallic, Masculine, Heroic | Reading |

| Heroic Homosex Home | Cockrub Warriors Home | Heroes Home | Story of Bill and Brett Home | Frot Club Home |

| Definitions | FAQs | Join Us | Contact Us | Tell Your Story |

© All material on this site Copyright 2001 - 2011 by Bill Weintraub. All rights reserved.