The Mingling of Their Bones

2-28-2007

Having looked at, over the President's Day weekend, a mad scientist up in Oregon who's determined to figure out why rams are into rams, and has therefore been with great gusto killing the rams and dissecting their brains;

and some high school wrestlers in Connecticut who've been, in the name of gender parity, strong-armed into grappling with girls -- even though no one interviewed for the article thinks that's a particularly good idea -- for either the boys or the girls;

and a whole slew of American librarians and public school teachers who believe that books containing the word scrotum should be burned --

I think it's time we return to the common sense and common decencies, such as they were, of the early Roman Empire, and a poet, Publius Ovidius Naso, known to us as Ovid.

Ovid of course is better known today than poor old Publius Papinius Statius.

Part of that may be deserved -- Ovid's a terrific writer.

But part of it I think also is that much of Ovid is about heterosexual love affairs.

Which are a lot easier on our heterosexualized sensibilities than the muscular masculine stripped to the skin hot raw sweat brawling of guys like Polynices and Tydeus.

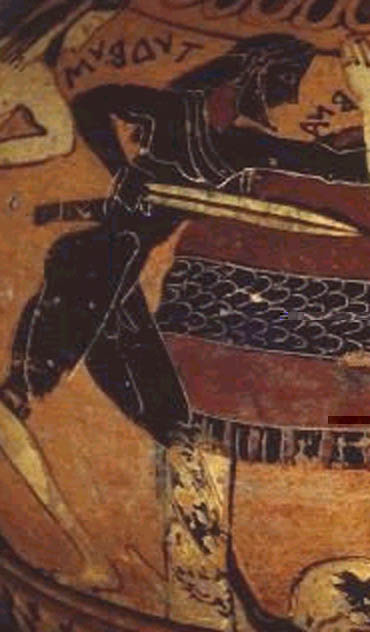

Tydeus

Not that everyone's always been fond of Ovid.

The notoriously prudish Emperor Augustus tolerated him for awhile and than banished him to the Black Sea.

Perhaps because of some indiscretion with a woman of high birth and high rank.

Nevertheless, in glancing -- and I do mean glancing -- through Ovid's best known work, the Metamorphoses, I came across the following references to same-sex love.

And I'm posting them here because I want you to understand how casually the Romans treated same-sex desire and same-sex affection.

They took it for granted, as you'll see, that boys would love boys and warriors warriors.

The first excerpt is from the story of Narcissus, the youth who fell in love with his own reflection, and died while gazing into his own eyes in a woodland pool:

Now Narcissus

Was sixteen years of age, and could be taken

Either for boy or man; and boys and girls

Both sought his love, but in that slender stripling

Was pride so fierce no boy, no girl, could touch him....

[Echo] was not the only one on whom Narcissus

Had visited frustrations; there were others,

Naiads or Oreads, and young men also

Till finally one rejected youth, in prayer,

Raised up his hands to Heaven: "May Narcissus

Love one day, so, himself, and not win over

The creature he loves." Nemesis heard him,

Goddess of Vengeance, and judged the plea was righteous.....

~ Metamorphoses III, translated by Rolfe Humphries

So here we can see that Ovid simply assumes, and presumably his audience too assumes, that boys will fall in love with other boys, and young men with young men;

and in Ovid's telling of the tale, Narcissus, though he'd rejected many girls, is punished because of the prayer of another youth -- another teen-aged boy.

It's very striking, because in our scrotum-phobic culture, if one of those high-school wrestlers the Times wrote about fell in love with one of his buddies -- and talked about it -- there would be a major upheaval for the team, the school, the parents, etc.

And the boys themselves.

Huge upheaval.

And of course no doubt some of those high-school wrestlers do have crushes on other male wrestlers --

but those crushes are completely hidden and suppressed, self-censored and repressed.

Whereas in Ovid, when Narcissus rejects a fellow teen-aged boy, the boy prays openly to Heaven, and Nemesis responds to his prayer.

Which means that in Ovid, God -- or at least the gods -- hear(s) the prayers of a same-sex smitten lover.

I wonder what Ted Haggard -- or the Anglican Communican -- would have to say about that?

Of course, the way the prayer is answered results in the destruction of Narcissus -- actually, he's not so much destroyed as he is turned into a flower, and thus immortalized.

Hmmmmm.

Haggard, and the Anglicans, who've gone berserk in their opposition to gay bishops and same-sex unions, would probably say that we're fortunate today to no longer live under the sway of such petulant and capricious deities.

Who change young men into flowers.

But there are worse fates after all.

Such as believing that you're denied entrance to the Kingdom of Heaven;

and being told to get out of town and never preach again;

and committing suicide.

Let's look at some pix.

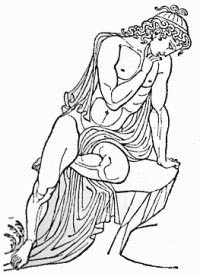

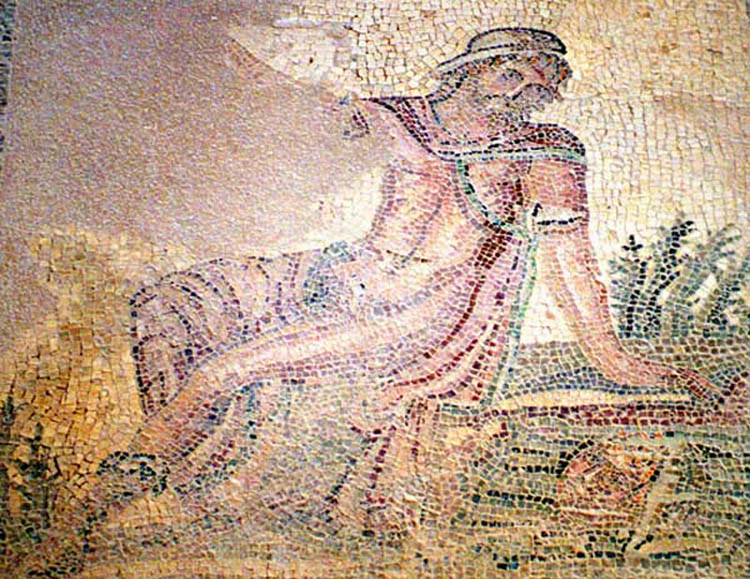

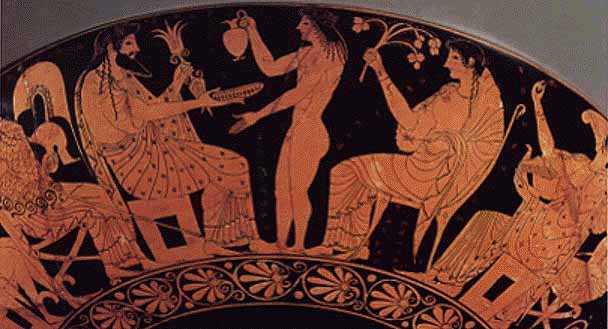

This is a Roman mosaic of Narcissus:

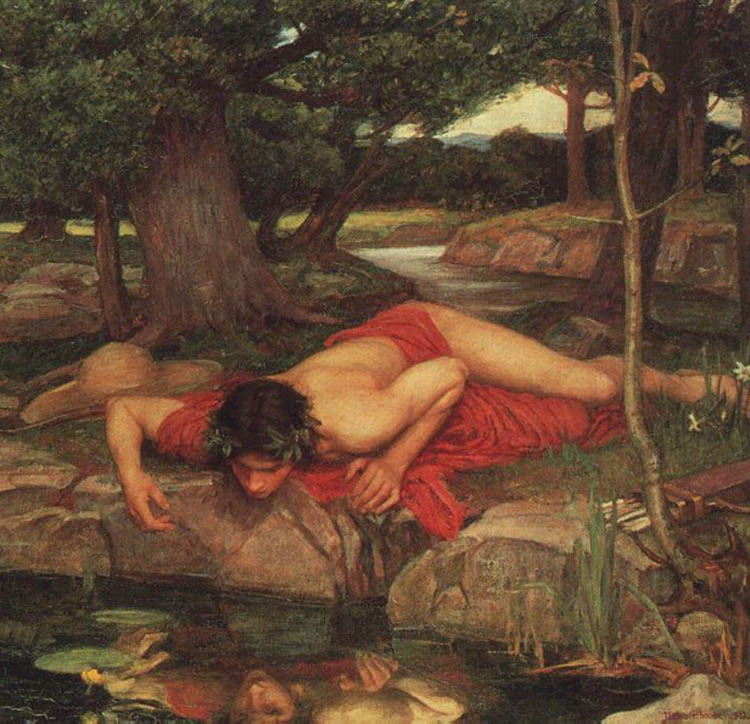

And here are a couple of much later European paintings -- 18th and 19th century.

In both of them, the nymph Echo is still visible.

But in the myth, by the time Narcissus starts gazing at his reflection in the pool, Echo's body has withered away, and she's just -- an echo.

Still here we see her with Narcissus and an infantilized Eros:

And this is a very lovely painting in the style of the pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood:

And here's the detail of Narcissus:

A couple of points:

First off, while Echo is certainly part of the myth, her presence in these paintings makes it appear that she brought the curse down upon Narcissus.

No.

It was another youth.

The story is male-male.

Secondly, the Narcissus myth is a same-sex love story, of sorts, and in our era it's been used to beat up on gay-identified men, who are accused of narcissism.

But to the Greeks -- and certainly to Ovid -- this myth was about the dire consequences of rejecting love.

Which is what Narcissus had done with both male and female suitors.

And there are other Greek myths -- most notably that of Hippolytus -- in which a male who rejects love is dreadfully punished.

So we need to understand that the Narcissus myth was not intended as a critique of same-sex love.

Rather, it's critical of someone who rejects love.

And of course someone who can love only himself.

In this next excerpt, a couple of young warriors get involved in a battle against the great hero Perseus, who killed the Gorgon Medusa and rescued Andromeda, etc --

and they don't fare very well.

There was a youngster there, Athis, from India,

Whose mother was a river-nymph, Limnaee,

And he was beautiful, with beauty doubled

By the rich robes he wore, the purple mantle

With fringe of gold, and a golden chain adorning

His throat, and a golden circlet holding in

His hair, perfumed with myrrh. At sixteen years

He threw the javelin well, and bent the bow

With even greater skill, and would have bent it

Once more, but Perseus, snatching from the altar

A smoldering brand, used it for club and battered

His face to splintered bones.And this was seen

By Lycabas, who loved him, very dearly,

As one boy loves another, and who wept

For Athis, gasping out his life, his features

Fouled in his lifeblood, and he seized the bow

Which Athis once had bent. "You have me to fight,"

He cried, "It will not be long, the cheap rejoicing

In having killed this boy: all that you gain

Is hate, not praise!" As the last words were spoken

The arrow was on its way, but missed, and fastened harmless

In Perseus' robe, and Perseus turned, and swung

The scimitar that once had slain the Gorgon

And now slew Lycabas, who, in the darkness

That swam before his eyes, looked once around

For Athis, and once more lay down beside him

And took this comfort to the world of shadows

That in their death the two were not divided.~ Metamorphoses V, translated by Rolfe Humphries

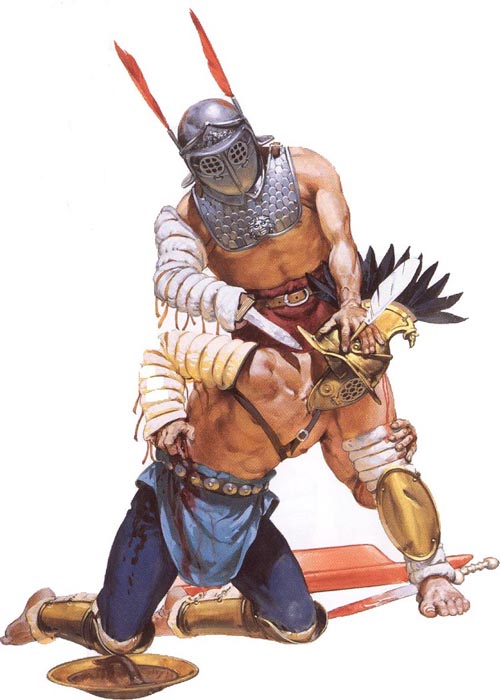

So again, we have the love of two youths, two warrior youths, presented matter of factly.

Lycabas, we're told, loved Athis, "very dearly, as one boy loves another."

And when Lycabas is killed attempting to avenge Athis, he

once more lay down beside him

And took this comfort to the world of shadows

That in their death the two were not divided.

This is a common theme in ancient literature, warrior-lovers who die fighting the same foe, who die for each other and die together.

And the Romans seemed to like the idea that in death their bodies would arrange themselves decorously, either side by side or one atop the other.

For example, Virgil, who was a contemporary of Ovid's, has a pair of warrior-lovers in the Aeneid -- Euryalus and Nisus -- who are killed behind enemy lines.

Euryalus is killed first, and Nisus dies while killing the man who'd killed his lover:

So he took that life

Even as he died himself. Pierced everywhere,

He pitched down on the body of his friend

And there at last in the peace of death grew still.~ Aeneid IX, translated by Robert Fitzgerald

This is a model of male-male devotion and not just male-male, but warrior-warrior, which clearly had great appeal for the ancients.

They like the idea of these guys not just dying together but of lying together in death and of being together in the next world.

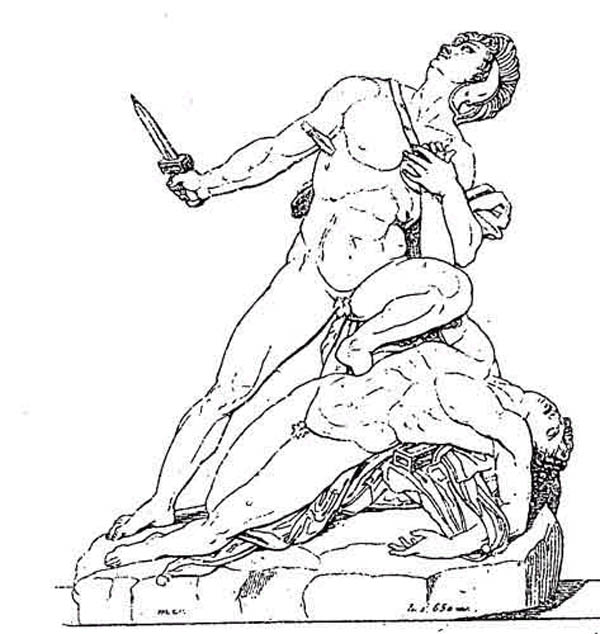

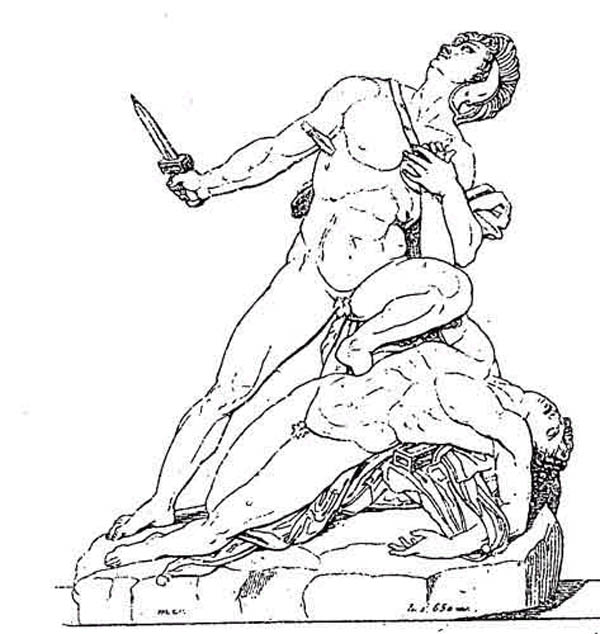

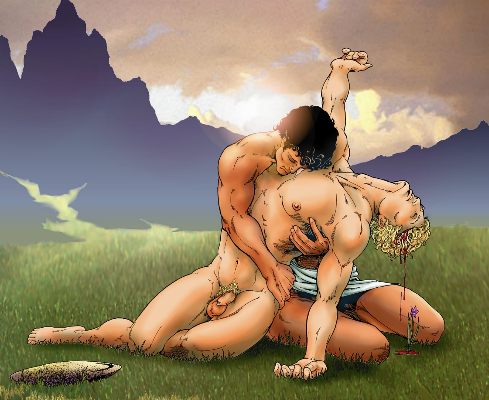

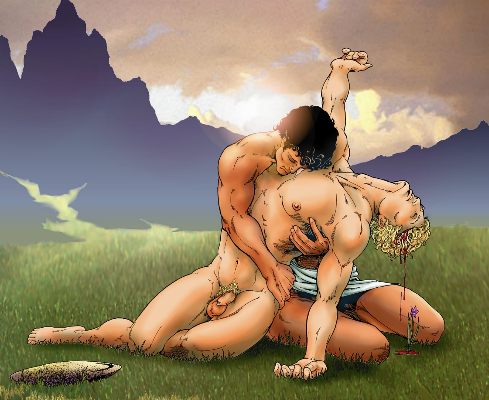

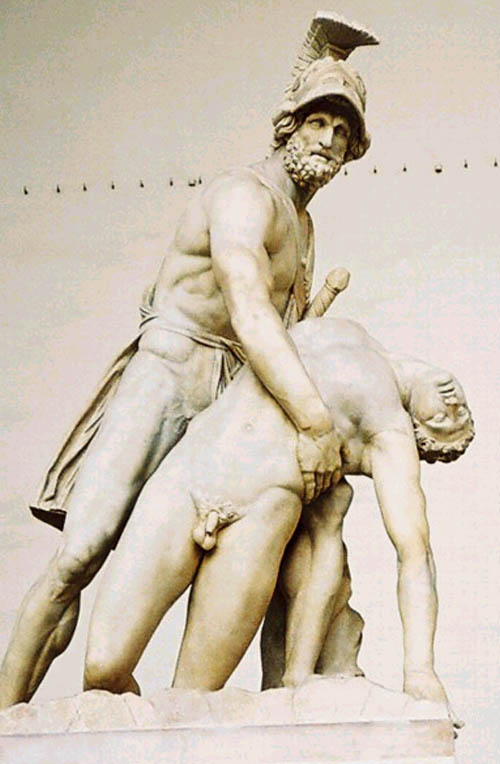

These next pictures are of a sculpture which stands in the courtyard of the Louvre and depicts Euryalus and Nisus.

This is NOT an ancient Greek or Roman work; it's 19th-century.

This is a drawing of the piece:

This is the face of Nisus himself from the sculpture:

And it would appear that when Nisus falls he and Euryalus will be in a full frontal embrace.

Now, I said that the ancients liked the idea of these guys not just dying together but of lying together in death and of being together in the next world.

And that dates back to at least Homer.

In the Iliad, which had for the Greeks the force the Bible has for us, after Patroclus is killed, his ghost comes to Achilles and says, Cremate me and put my bones and ashes in an ossuary -- a box -- and after you're killed, have our fellow warriors mix your bones and ashes with mine.

Obviously that's a very intimate act.

And obviously it appealed to the Romans as well as the Greeks -- they like the idea of the warrior bodies being joined in death.

What's left after cremation, by the way, are bones and ashes.

In America, crematories pulverize the bones and then present the "ashes" -- which are actually ashes and fragments of bone -- to the survivors.

But in ancient Greece, the bones and ashes were put in a container called an ossuary:

This ossuary dates from the era of Alexander the Great -- ca 330 BC -- but I've always liked to think that it resembles the ossuary of Achilles and Patroclus.

It has a truly barbaric look.

This is another bone-containing box -- it's solid gold, and it's thought to have contained the bones of Phillip II -- Alexander's father.

What I want you guys to see here is how intimate these boxes are.

So when the ancients spoke of mixing together two men's bones and ashes -- it's as intimate a mingling as one can imagine.

And it would have been expected by a Roman audience that the remains of Euryalus and Nisus would be treated the same way.

This is a very romantic notion.

And clearly, when it comes to the Love of Warriors, both the Greeks and the Romans were, on the whole, romantics.

Not Ovid -- by the way.

At least to my thinking.

Ovid too often seems to be laughing at the loves of his mythological beings.

And that I suspect is what got him exiled.

His laughter.

But Statius is a romantic, and on a grand scale.

Writing about and for people who appreciated grand gestures.

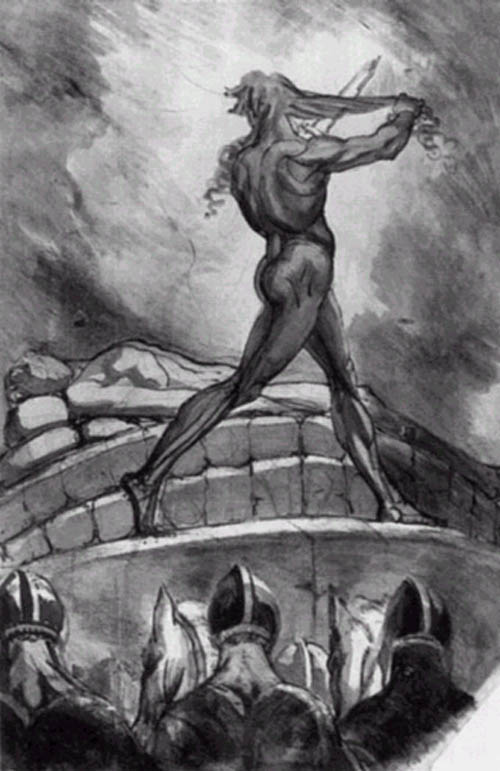

When, in the midst of a ferocious battle, Polynices falls naked and wailing on Tydeus' bloody corpse -- that's a grand gesture.

And it's related to the grandeur of Nature and the natural world, which plays a big role in Statius' work.

Let's look at two more male-male love stories as related by Ovid.

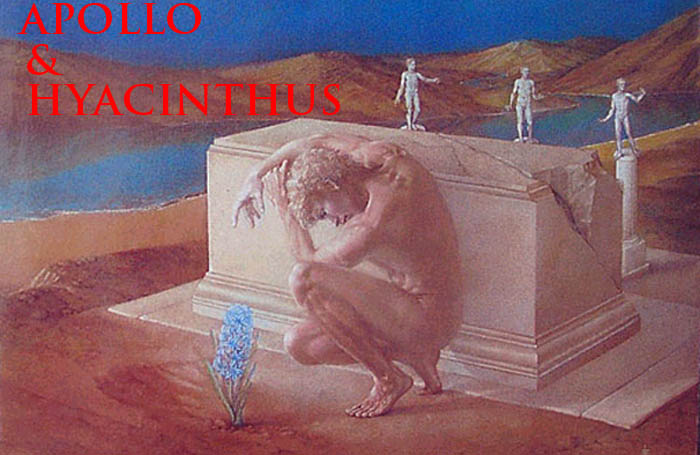

These are the stories of Zeus aka Jove and Ganymede; and Apollo and Hyacinth, which are presented together in the book -- as they are here.

The teller of these tales is Orpheus himself -- you can't do better than that:

The Story of Ganymede, a Very Brief One

The king of the gods once loved a Trojan boy

Named Ganymede; for once, there was something found

That Jove would rather have been than what he was.

He made himself an eagle, the only bird

Able to bear his thunderbolts, went flying

On his false wings, and carried off the youngster

Who now, though much against the will of Juno,

Tends to the cups of Jove and serves his nectar.

|

There was another boy, who might have had

|

|

So, in a garden,

~ Metamorphoses X, translated by Rolfe Humphries |

Now, Apollo, like his sister Artemis, never married.

And what's interesting, when we look at the way the gods relate to the mortal women whom they impregnate, as opposed to the mortal youths whom they love, is that very often -- I don't say always, but often -- what a god will do is have sex with a woman and get her pregnant -- in many instances it's very close to, or just plain is, rape -- and then never see her again.

He doesn't have an affair with her.

He desires her sexually and sleeps with her once, and leaves her.

She bears his illegitimate child or children -- and there are often problems as a result.

But -- and conveniently for the noble houses of Greece -- because of the many women who were alleged to have been impregnated in that way, any number of royal and aristocratic families in ancient Greece were able to claim descent from a god.

Even though the god was nothing more than a sperm machine.

Whereas, the gods' relationships with boys are romantic and sustained.

And clearly that mirrored what the Greeks saw as the difference between procreative relationships with women, and romantic relationships with men.

For example, notice that Zeus takes Ganymede back to Olympus where he's permanently in residence as cup-bearer.

The myth doesn't say, Zeus desired Ganymede, had sex with him once, and never saw him again.

The myth says, Zeus loved him and took him to Olympus where he now serves Zeus his nectar.

Similarly, Apollo and Hyacinth are hanging out together -- they strip, they oil their bodies, they start playing with the discus.

Guy stuff.

They're guys together.

This is why some people have said that in the ancient world, men had sex with women for procreation, and with men for pleasure.

I think that's extreme.

But there's no question that in the stories of the gods and their mortal male lovers, the gods spend more time with the males than they ordinarily do with the women they impregnate.

For example, Zeus impregnates the mortal woman Alcmene -- who bears Heracles -- the greatest Greek hero.

Now, because Zeus has special plans for Heracles, Zeus takes longer than usual to impregnate Alcmene; he more or less suspends time and makes the night three times as long so that he can spend an appropriately long time making sure she's pregnant.

As the great classicist and poet Robert Graves says, "because the procreation of so great a hero as Zeus had in mind could not be accomplished in haste."

But once that's done, Zeus returns to Olympus and basically never sees her again.

It's true that he treats her well during sex -- "instead of roughly violating her," says Graves --

But afterwards he cares about his son -- Heracles -- not the boy's mother.

So: the gods have sex with mortal women; they have relationships with mortal males.

And that's very clear in Ovid and his telling of the story of Apollo and Hyacinth.

Apollo spends time with Hyacinth -- and if we can believe Ovid, would have liked to have made him immortal.

Now, as it happens, there's another version of the story of Apollo and Hyacinth.

And that's the one in which Hyacinth is killed by the West Wind -- Zephyros -- because he won't be unfaithful to Apollo.

And that's the version, I suspect, which was told at Sparta.

That Ovid doesn't use that version of the myth, which is more interesting, dramatically speaking, than the other, suggests that Ovid didn't know it.

We know it via a Greco-Roman author named Pausanias, who lived after Ovid, and who visited Sparta.

Here's the story as summarized by Graves:

There was also the case of the beautiful youth Hyacinthus, a Spartan prince, with whom not only the poet Thamyris fell in love -- the first man who ever wooed one of his own sex -- but Apollo himself, the first god to do so. Apollo did not find Thamyris a serious rival; having overheard his boast that he could surpass the Muses in song, he maliciously reported it to them, and they at once robbed Thamyris of his sight, his voice, and his memory for harping. But the West Wind [Zephyros] had also taken a fancy to Hyacinthus, and became insanely jealous of Apollo, who was one day teaching the boy how to hurl a discus, when the West Wind caught it in mid-air, dashed it against Hyacinthus's skull, and killed him. From his blood sprang the hyacinth flower, on which his initial letters are still to be traced.

~ Pausanius via Robert Graves, The Greek Myths 21.m.

Why would the Spartans have preferred this version?

Because in it, Hyacinthus is loyal to Apollo.

He spurns Zephyros.

And that's how the Spartans -- and the other Greeks -- expected male lovers to behave.

Faithfully.

Of course Ovid isn't Greek, he's Roman.

But in bringing him to your attention, I want to give you a sense of how even the Romans depicted male-male love.

And Ovid is very explicit.

For example, there's a moment during the hunt for the Calydonian boar -- a really monstrous wild pig -- when the Athenian hero Theseus becomes alarmed because some other heroes have been killed by the boar; and he calls out to his companion Pirithous,

"Stay out of it, stay far away, dear comrade,

Dearer than my own life to me. Brave men

Can fight long range, with no disgrace..."~ Metamorphoses VIII, translated by Rolfe Humphries

That's a Roman telling of a Greek myth.

Now, the Romans were not, in many ways, what we would call real genial folks.

They killed and enslaved hundreds of thousands of people in their various wars; and of course killed tens of thousands more in their arenas.

And most Roman writers have a contempt not just for non-Romans, but for anyone other than high-born Romans, which is startling.

For example, Tacitus says at one point of some very powerful man -- Drusus, son of the emperor Tiberius -- that he was "abnormally fond" of the blood spilled by gladiators in the arena.

Then Tacitus adds: "Admittedly it was worthless blood, but the public was shocked ..."

"Worthless blood"

Nice guy, huh?

Still, when it comes to same-sex affection, it's difficult to imagine the Romans being as silly -- and DESTRUCTIVE -- as are present-day Americans.

The Romans certainly would not have thought it strange for one ram to try to get it on with another.

They would have seen that as natural.

And they wouldn't have killed the ram on that account.

Of course they sacrificed animals like rams to their gods -- gods like Mars.

But then they ate the animal -- they didn't just throw it away in the name of some utterly senseless "scientific" experiment.

And the idea that boys should learn to fight in all-male environments would have been obvious to them.

And they wouldn't have had a problem with the word scrotum.

So in many ways they were a lot more reasonable than the various imperial peoples who've succeeded them.

Now: in Ovid's version of the Hyacinthus myth, Apollo tells the dying Hyacinth

You will be reborn

As a new flower whose markings will spell out

My cries of grief, and there will come a time

When a great hero's name will be the same

As this flower's markings.'So Apollo spoke,

And it was truth he told, for on the ground

The blood was blood no longer; in its place

A flower grew, brighter than any crimson,

Like lilies with their silver changed to crimson.

That was not all; Apollo kept the promise

About the markings, and inscribed the flower

With his own grieving words: Ai, Ai

The petals say, Greek for Alas!

Apollo says, A great hero's name will be the same as this flower's markings.

Who is this hero?

He's the great Greek hero Ajax, who fights in the Trojan war alongside of such heroes as Odysseus and Diomedes and Achilles and Patroclus.

And his fate, it turns out, is intertwined with that of Achilles and Patroclus, the greatest heroes of their age, and the greatest models of male-male love for the ancient Greeks.

It's not surprising then that Statius, having written the Thebaid -- the story of the Seven Against Thebes and in particular the story of Polynices and Tydeus -- would turn to the Achilleid -- the story of Achilles and Patroclus.

For one thing because the Trojan War took place after the war against Thebes.

It may be surprising to us, but there was a chronology to much of Greek and Roman myth.

Events occurred in a certain order.

So Polynices and Tydeus marched against Thebes.

They were both killed; but Tydeus' son Diomedes survived him and lived first to take his revenge against the Thebans; and then to take part in the Trojan War.

Where he was a comrade of men like Odysseus and Ajax.

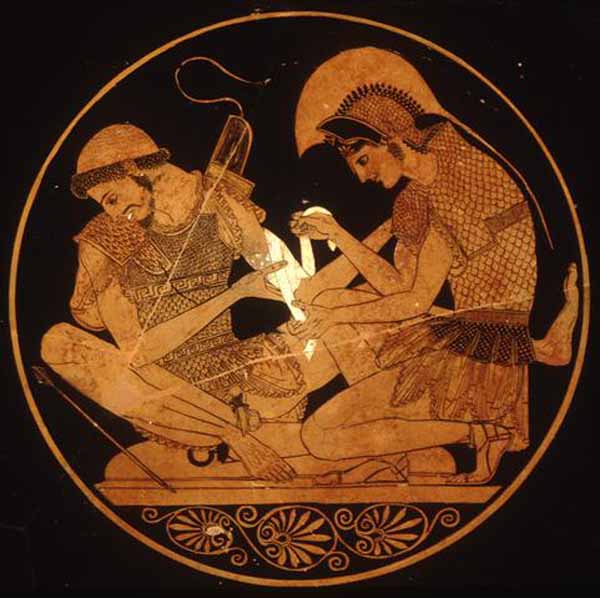

Let's go through the Achilles-Patroclus story in art -- mainly Greek -- and in the Iliad as translated by Richmond Lattimore.

xxx

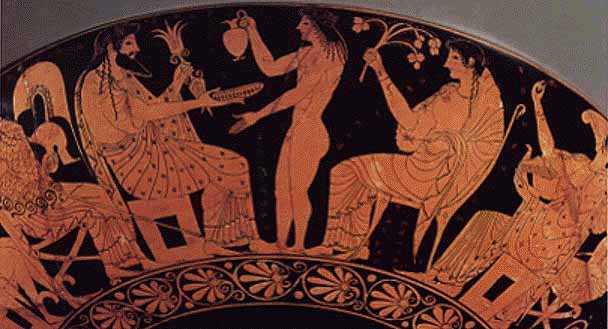

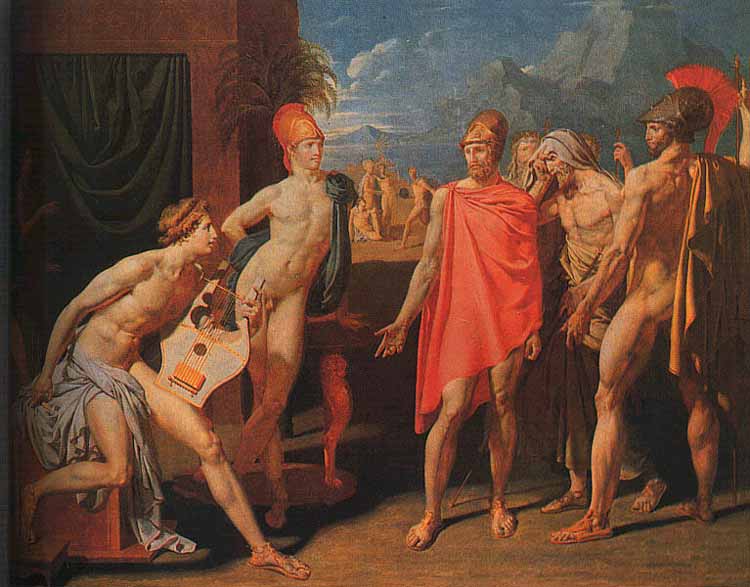

Here are Achilles and Patroclus fresh from battle, and Achilles is tending Patroclus' wound.

Both men are nude from the waist down, as they would have been during battle.

And a lot of the rest of the time.

Their environment is homosocial, and dominated by nude males.

Next, in this 19th century picture by Ingres, we see Achilles and Patroclus, both on the left, hanging out nude in their encampment at Troy:

Achilles has left the fight against the Trojans because of a dispute with the Greek leader Agamemon.

The war has gone badly in his absence, and ambassadors from Agamemnon have come to beg him to return to battle.

He refuses.

But when the Greeks are in danger of being over-run, and their ships set afire, Patroclus puts on Achilles' armor, goes into battle without him, leads the Greeks in a ferocious rally, and comes close to singlehandedly taking Troy.

Apollo, however, who supports the Trojans, knocks Patroclus down with supernatural force, stunning him, and then loosens his armor, leaving him vulnerable to attack from behind.

One Trojan stabs him in the back and runs away, and then the Trojan hero Hector kills him.

This is the scene as described by Homer:

And Patroclus charged with evil intent upon the Trojans.

Three times he charged in with the force of the running war god

screaming a terrible cry, and three times he cut down nine men;

but as for the fourth time he swept in, like something greater

than human, there, Patroklos, the end of your life was shown forth,

since Phoibos [Apollo] came against you there in the strong encounter

dangerously, nor did Patroklos see him as he moved through

the battle, and shrouded in a deep mist came in against him

and stood behind him, and struck his back and his broad shoulders

with a flat stroke of the hand so that his eyes spun; Phoibos

Apollo now struck away from his head the helmet

four-horned and hollow-eyed and under the feet of the horses

it rolled clattering, and the plumes above it were defiled

by blood and dust. Before this time it had not been permitted

to defile in the dust this great helmet crested in horse-hair;

rather it guarded the head and the gracious brow of a godlike

man, Achilleus; but now Zeus gave it over to Hektor

to wear on his head, Hektor whose own death was close to him.

And in his hands was splintered all the huge, great, heavy,

iron-shod, far-shadowing spear, and away from his shoulders

dropped to the ground the shield with its shield sling and its tassels.

The lord Apollo, son of Zeus, broke the corselet upon him.

Disaster caught his wits, and his shining body went nerveless.He stood stupidly and from close behind his back a Dardanian

man hit him between the shoulders with a sharp javelin;

Euphorbos, son of Panthoos, who surpassed all men of his own age

with the throwing spear, and in horsemanship and the speed of his feet. He

had already brought down twenty men from their horses

since first coming, with his chariot and his learning in warfare.

He first hit you with a thrown spear, o rider Patroklos,

nor broke you, but ran away again, snatching out the ash spear

from your body, and lost himself in the crowd, not enduring

to face Patroklos, naked as he was, in close combat.Now Patroklos, broken by the spear and the god's blow, tried

to shun death and shrink back into the swarm of his own companions.

But Hektor, when he saw high-hearted Patroklos trying

to get away, saw how he was wounded with the sharp javelin,

came close against him across the ranks, and with the spear stabbed him

in the depth of the belly and drove the bronze clean through. He fell,

thunderously, to the horror of all the Achaian people.As a lion overpowers a weariless boar in wild combat

as the two fight in their pride on the high places of a mountain

over a little spring of water, both wanting to drink there,

and the lion beats him down by force as he fights for his breath, so

Hektor, Priam's son, a close spear-stroke stripped the life

from the fighting son of Menoitios, who had killed so many.

And stood above him, and spoke aloud the winged words of triumph:'Patroklos, you thought perhaps of devastating our city,

of stripping from the Trojan women the day of their liberty

and dragging them off in ships to the beloved land of your fathers.

Fool! When in front of them the running horses of Hektor I

strained with their swift feet into the fighting, and I with my own spear

am conspicuous among the fighting Trojans, I who beat from them

the day of necessity. For you, here the vultures shall eat you.

Wretch! Achilleus, great as he was, could do nothing to help you.

When he stayed behind, and you went, he must have said much to you:

"Patroklos, lord of horses, see that you do not come back to me

and the hollow ships, until you have torn in blood the tunic

of manslaughtering Hektor about his chest." In some such

manner he spoke to you, and persuaded the fool's heart in you.'And now, dying, you answered him, o rider Patroklos:

'Now is your time for big words, Hektor. Yours is the victory

given by Kronos' son, Zeus, and Apollo, who have subdued me

easily, since they themselves stripped the arms from my shoulders.

Even though twenty such as you had come in against me,

they would all have been broken beneath my spear, and have perished.

No, deadly destiny, with the son of Leto, has killed me,

and of men it was Euphorbos; you are only my third slayer.

And put away in your heart this other thing that I tell you.

You yourself are not one who shall live long, but now already

death and powerful destiny are standing beside you,

to go down under the hands of Aiakos' great son, Achilleus.'He spoke, and as he spoke the end of death closed in upon him,

and the soul fluttering free of his limbs went down into Death's house

mourning her destiny, leaving youth and manhood behind her.

Now though he was a dead man glorious Hektor spoke to him:

'Patroklos, what is this prophecy of my headlong destruction?

Who knows if even Achilleus, son of lovely-haired Thetis,

might before this be struck by my spear and his own life perish?'He spoke, and setting his heel upon him wrenched out the bronze spear

from the wound, then spurned him away on his back from the spear. Thereafter

armed with the spear he went on, aiming a cast at Automedon,

the godlike henchman for the swift-footed son of Aiakos,

with the spear as he was carried away by those swift and immortal

horses the gods had given as shining gifts to Peleus.

So: Patroclus dies, but only because Apollo has moved against him.

Now, notice that Hector recognizes the special relationship between Achilles and Patroclus, and so does Patroclus, who tells Hector that Achilles will now most certainly kill him.

Indeed, Hector goes so far as to imagine a conversation between Achilles and Patroclus in which Achilles says, "see that you do not come back to me..."

To *me*

It's very striking.

And Patroclus responds that because of what Hector has done,

death and powerful destiny are standing beside you,

to go down under the hands of Aiakos' great son, Achilleus.'

So Patroclus is clear that by killing him, Hector has guaranteed that Achilles will kill -- Hector.

But before that can happen, there's a struggle over Patroclus' body.

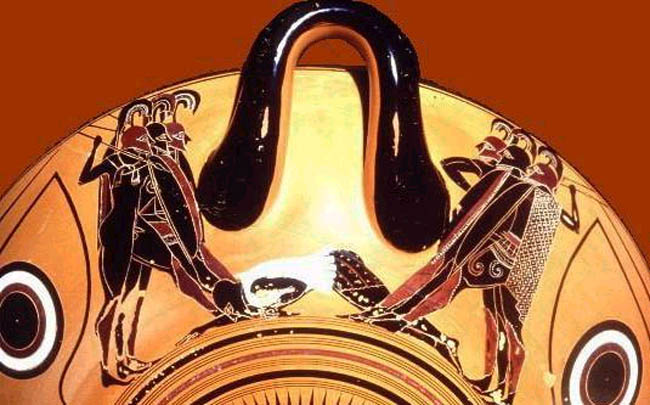

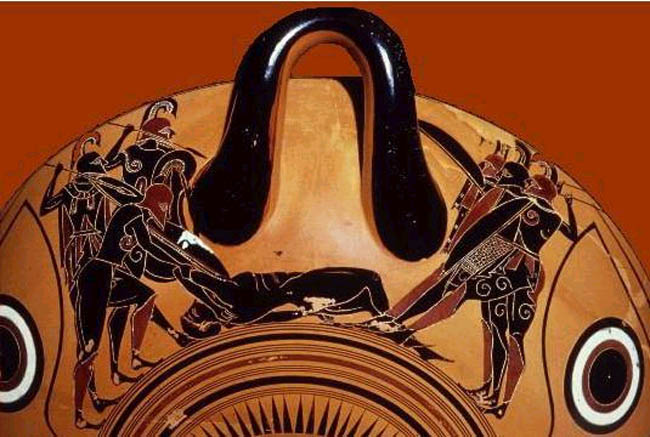

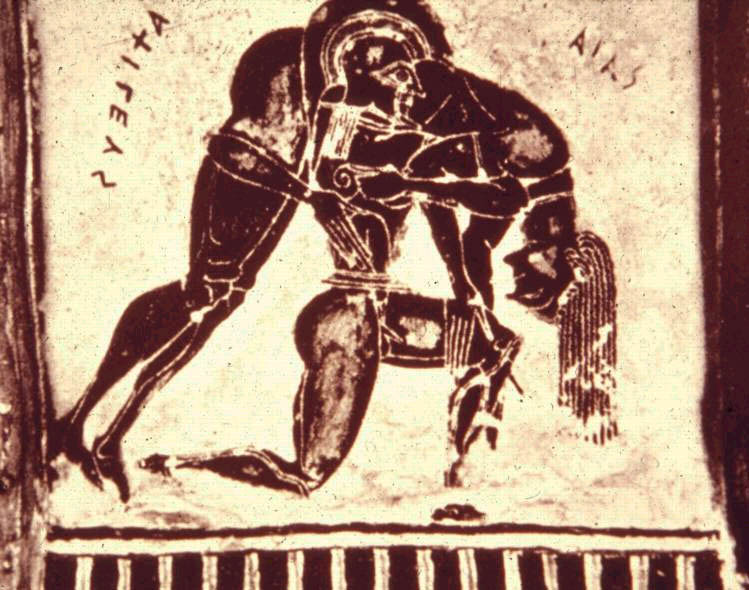

In these next two pix, we see the Greeks, on the left, fighting the Trojans for possession of Achilles' armor and Patroclus' body.

In the first pic, Patroclus still wears the armor.

Here, the Trojans have succeeded in stripping Patroclus' body of Achilles' armor, but the Greeks, led by Ajax, are about to get the body itself.

In this Hellenistic sculpture, the Greek warrior Menelaus, who fought beside Ajax in the battle for Patroclus' body, carries it back to the Greek camp and Achilles.

When Achilles learns of Patroclus' death, he goes berserk.

His mother Thetis brings him a new set of armor, and he storms into battle and kills Hector.

After killing Hector, Achilles considers doing further damage to the Trojans, but then says to his fellow warriors,

There is a dead man who lies by the ships, unwept, unburied:

Patroclus: and I will not forget him, never so long as

I remain among the living and my knees have their spring beneath me.

And though the dead forget the dead in the house of Hades,

Even there I shall still remember my beloved companion.

Achilles then ties Hector's body to his chariot and gallops around the walls of Troy, desecrating the corpse.

Achilles returns to the Greek encampment with Hector's desecrated body, and lays it in the dust by Patroclus' body, which has been placed on a bier prior to cremation.

Agamemnon suggests that Achilles "wash away the filth of the bloodstains," but Achilles refuses, saying

No, before Zeus, who is greatest of gods and the highest,

there is no right in letting water come near my head until

I have laid Patroclus on the burning pyre, and heaped the mound over him,

and cut my hair for him, since there will come no second sorrow

like this to my heart again while I am still one of the living.

There is then a funeral feast, and the men eat and fall asleep.

But not Achilles.

He wanders for a while on the beach, "groaning heavily," and at last, exhausted both by his beloved companion's death and the battle with Hector, he too falls asleep.

The next two pix are by the 19th-century romantic artist Fuseli.

The first depicts what is certainly the most emotionally-compelling moment of the Iliad: Achilles' dream.

Patroclus' body has been left uncremated.

Which means his soul cannot rest.

And, in a brilliant but agonizing scene, Patroclus comes to Achilles in a dream, urges him to burn his body, and asks that their ashes be mixed together after Achilles' own death, an act of great intimacy.

Achilles readily agrees, and then attempts to hold Patroclus, saying, "Let us, if only for a little, embrace, and take full satisfaction from the dirge of sorrow."

Achilles reaches for Patroclus, but as he does, Patroclus vanishes, and Achilles wakes, alone and bereft, in misery, wonder, and despair.

Nevertheless, Achilles is now ready for Patroclus' cremation.

The warriors carry Patroclus toward the pyre, and as they do

They covered all the corpse under the locks of their hair, which they cut off

and dropped on him, and behind them brilliant Achilleus held the head

sorrowing, for this was his true friend he escorted toward Hades.When these had come to the place Achilleus had spoken of to them

they laid him down, and quickly piled up the abundant timber.

And now brilliant swift-footed Achilleus remembered one more thing.

He stood apart from the pyre and cut off a lock of fair hair

Which he had grown long to give to the river Spercheiros, and gazing

in deep distress over the wine-blue water, he spoke forth:

"Spercheiros, it was in vain that Peleus my father vowed to you

that there, when I had won home to the beloved home of my fathers,

I would cut my hair for you and make you a grand and holy

sacrifice of fifty rams consecrate to the waters ...Now, since I do not return to the beloved land of my fathers,

I would give my hair into the keeping of the hero Patroclus."He spoke, and laid his hair in the hands of his beloved

companion, and stirred in all of them the passion of mourning.

Accompanied by sacrifices, both animal and human, the body is burned.

And as

a father mourns who burns the bones of a son, who was married

only now, and died to grieve his unhappy parents,

so Achilleus was mourning as he burned his companion's

bones, and dragged himself by the fire in close lamentation.

As dawn comes, the fire dies down and Achilles falls asleep.

He's awakened by Agamemnon, and Achilles asks his help in gathering up Patroclus' bones:

And let us lay his bones in a golden jar and a double

fold of fat, until I myself enfold him in Hades.

And Achilles asks also that they build a grave mound, which will contain the jar and eventually, the bones of both men.

There are then funeral games.

Even after Patroclus has been burned and buried, though, Achilles bitterly refuses to return Hector's body to the Trojans.

Finally Hector's aged father Priam comes to beg for the body of his son.

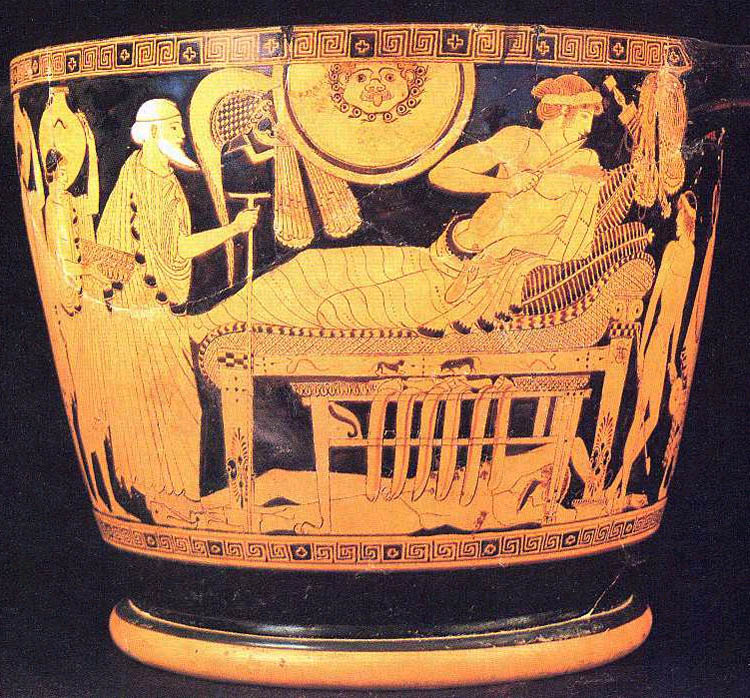

In this painting, Achilles reclines and refuses to talk to him.

The small figure on the right might be Achilles' son Neoptolemus -- who was conceived on Scyros -- or perhaps a slave.

The figure beneath the bed is of course Hector, who has indeed suffered the fate that Patroclus promised him.

Eventually, however, Achilles relents and returns Hector's body to the Trojans.

And here the Iliad ends.

However, the story continues.

Achilles returns to the battle and is himself killed -- again, through the agency of Apollo.

His body is retrieved by the Greek hero Ajax -- who also fought for the body of Patroclus.

Achilles too is cremated and his bones and ashes mixed with those of Patroclus:

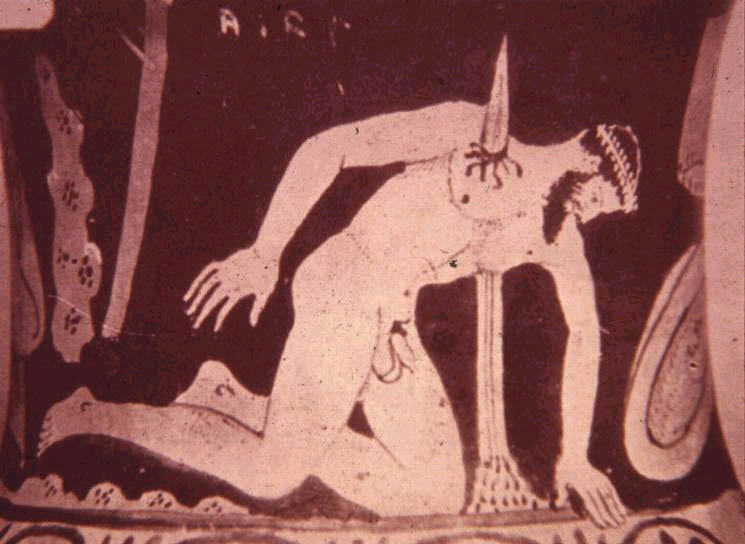

Ajax asks to be given Achilles' armor.

When he's denied, he kills himself.

Here's how Ovid describes his death:

Then he, who had stood so often

Alone against great Hector, stood so often

Alone against sword and fire and Jove himself,

Could make no stand against his single anger;

Unconquered, he was conquered by his sorrow.

He snatched the sword, he cried: "This is my own,

Most certainly, or does Ulysses claim it?

This I must use against myself; the sword,

So often red with Trojan blood, will redden

Now with its master's, and no man but Ajax

Will ever conquer Ajax!" And he drove

Deep in the breast which no man ever wounded

The deadly steel. No hand was strong enough

To draw that weapon out; the blood of Ajax

Flooded it loose: from the green ground, now crimson,

A crimson flower grew, like that which blossomed

From Hyacinthus' wound, and on the petals

The markings honor man and boy together,

AIAS, they read, for Ajax, and AI AI,

Alas! for both.~ Metamorphoses XIII, translated by Rolfe Humphries

What does Ajax have to do with Hyacinth?

It's not clear, other than this:

In the Iliad, it's Ajax who most tenaciously fights for the bodies first of Patroclus and then of Achilles.

So that it's through Ajax that the bones of these great heroes can be interred -- together.

And that may be why he's connected in myth with Hyacinth and Apollo.

Who too were lovers -- and loyal unto death.

According to Robert Graves, there were many shrines to Achilles throughout the ancient world.

One was at Sparta -- where the Hyacinthia, the annual festival in honor of Hyacinthus, was celebrated by nude Spartan youths.

According to Graves, those same youths sacrificed to the spirit of the dead hero Achilles before -- FIGHTING:

On the road which leads northwards from Sparta stands a sanctuary built for Achilles by Prax, his great-grandson, which is closed to the general public;

but the boys who are required to fight in a near-by plane-tree grove enter and sacrifice to him beforehand.

~ Pausanias via Graves, The Greek Myths, 164.p.

So the Spartan youths were taught to honor not just Hyacinth, but Achilles as well.

They sacrificed to Achilles, to this greatest of Warriors, before fighting.

And in so doing they could not help remembering Patroclus too.

These young Spartan warriors would have been athletic and handsome.

But if they were to be loved -- and to be Men -- they had to be more than that.

Plato said of similar young men in Athens, and throughout ancient Greece, that the beloved is "not less worthy of praise for his goodness than for his beauty."

That idea has been part of the mythos and ethos of male-male love since at least Gilgamesh and probably long before -- you can hear it expressed clearly by Charles Eastman when he describes the Sioux Warrior brothers-unto-death:

The highest type of friendship is the relation of "brother-friend" or "life-and-death friend." This bond is between man and man, is usually formed in early youth, and can only be broken by death. It is the essence of comradeship and fraternal love, without thought of pleasure or gain, but rather for moral support and inspiration. Each is vowed to die for the other, if need be, and nothing denied the brother-friend, but neither is anything required that is not in accord with the highest conceptions of the Indian mind.

~ Charles Eastman, 1858-1939. The Soul of the Indian.

Plato: "not less worthy of praise for his goodness than for his beauty"

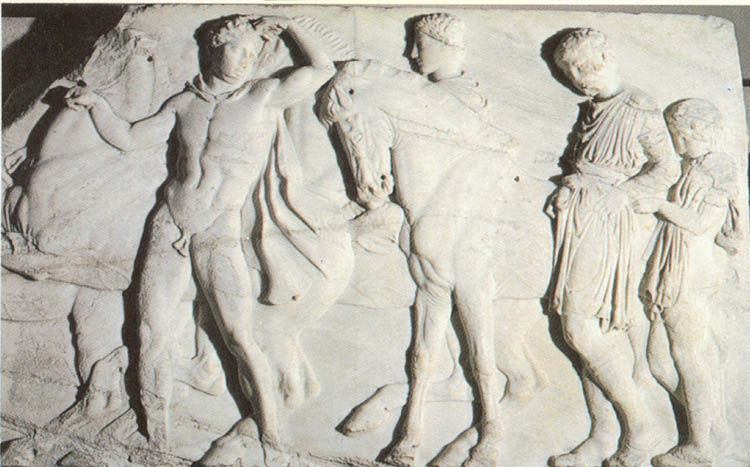

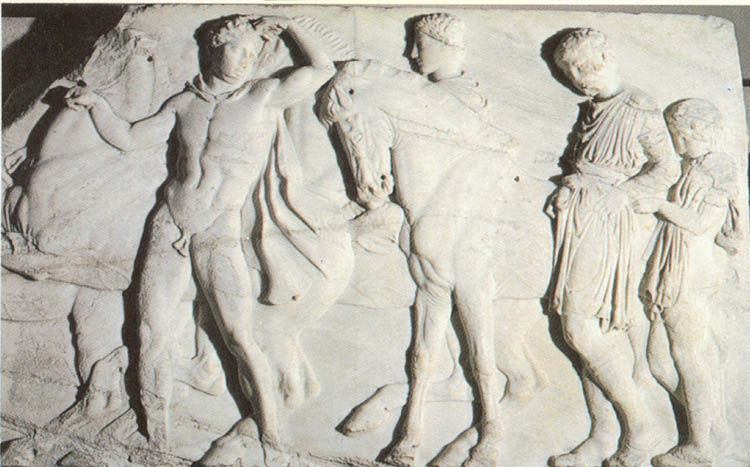

These are young horsemen from the frieze of the Parthenon.

In these young, self-assured men, in their homosocial space, we can see both goodness and beauty.

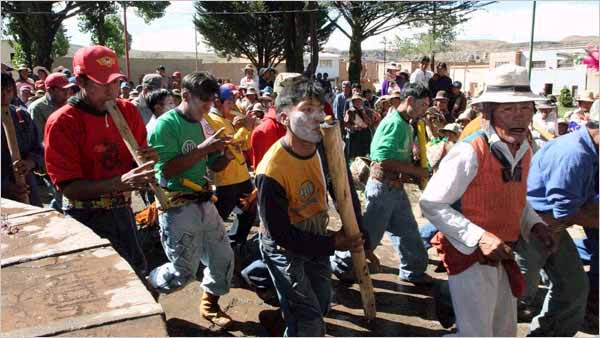

As we can in these young men celebrating the Amer Indian fighting festival known as Tinku.

These are the faces of Warrior Culture -- "not less worthy of praise for their goodness than for their beauty"

In Ovid, as in Statius, as in Virgil, and Homer, and so many other ancient authors, we can see the goodness and beauty of a culture which celebrated Warriors -- and the interment together of their bones.

The box containing Achilles and Patroclus' ashes was buried, it was believed, under a mound near Troy.

Alexander the Great, on his way to conquering Persia, visited the spot and ran naked around it in homage to these dead heroes, conquerors of Asia, who in death were not separated.

Both the comradeship of wounds -- and the mingling of their bones -- were part of their Warrior Way.

It is now left for us to re-discover what these ancient Warriors knew so well:

Bill Weintraub

February 28, 2007

© All material Copyright 2007 by Bill Weintraub. All rights reserved.

Re: The Mingling of Their Bones

3-1-2007

Hey Bill,

What a great article, just fantastic! What was amazing to me is not only the stories, but how the two sculptures of Euryalus/Nisus, and Meneleus/Patrokles affected me. The depth of emotion portrayed in them was very moving

Bill G

Add a reply to this discussion

AND

HEROES is presented by The Man2Man Alliance, an organization of men into Frot

To learn more about Frot, ck out What's Hot About Frot

Or visit our FAQs page.

| Heroes Site Guide | Toward a New Concept of M2M | What Sex Is |In Search of an Heroic Friend | Masculinity and Spirit |

| Jocks and Cocks | Gilgamesh | The Greeks | Hoplites! | The Warrior Bond | Nude Combat | Phallic, Masculine, Heroic | Reading |

| Heroic Homosex Home | Cockrub Warriors Home | Heroes Home | Story of Bill and Brett Home | Frot Club Home |

| Definitions | FAQs | Join Us | Contact Us | Tell Your Story |

© All material on this site Copyright 2001 - 2011 by Bill Weintraub. All rights reserved.