MANHOOD: A Reductional, Functional, Teleological, Incantational, and, above all, Sanctional --

Lexicon

Hi guy.

Welcome to Biblion Proton -- Book I -- of Manhood: A Lexicon.

My name is Bill Weintraub, and I'm the creator of The Man2Man Alliance and Ares is Lord websites, and the author of Manhood: A Lexicon.

Manhood: A Lexicon is, basically, a book -- masquerading as a webpage.

And, like any book, it's best read from the beginning.

So -- I strongly encourage you to read, if you haven't already, the Prefatory Note and Prolegomena to Manhood: A Lexicon, which precede Biblion Proton.

Reading that Prefatory Note and the Prolegomena will greatly aid your understanding of the material you encounter in Biblion Proton and the succeeding books of Manhood: A Lexicon.

July 4, 2013

BIBLION PROTON

By Bill Weintraub

Ιn Death of an AIDS Activist, we looked at this couplet from Book VIII of Plato's brilliant Republic:

And, I said,

That's from the Jowett translation, and Jowett actually says,

But, the word used for Virtue is, of course, areté, and as we've seen, and as I will continue to make clear and ever clearer, the term Virtue in archaic and classical Greece more often than not reduces to -- means:

As is explained in Liddell and Scott's Ancient Greek Lexicon Manhood.

"the first notion of goodness being that of manhood"

And, Liddell and Scott re-inforce that point by saying that areté is

Manhood.

"goodness, excellence, of any kind, esp. of manly qualities, manhood, valour, prowess"

Manhood:

The first notion of Goodness.

The first notion of Goodness is that of Manhood.

Manhood.

Areté is goodness and excellence, especially of manly qualities, bravery in war, that is valour and prowess -- which are, as we just learned in the Prolegomena, the two prime components of Manhood --

True Manhood, which is Fighting Manhood.

Valour is Willingness.

Prowess is Ability.

True Manhood is the Willingness and Ability to Fight.

Manhood.

Fighting Manhood.

And that Fighting Manhood is Excellence, Virtue, and Goodness.

Manhood is Excellence.

Manhood is Virtue.

Manhood is Goodness.

Fighting Manhood -- is Goodness.

Liddell and Scott, whose Ancient Greek Lexicon has been considered authoritative for well over a century -- say so.

They say that Fighting Manhood is the first notion of Goodness.

And -- and I'm repeating this purposefully -- Liddell and Scott re-inforce that point by saying that areté is

And, you'll notice, if you click on this link which takes you to Liddell and Scott's definition of areté, that they make the point even plainer by putting the word areté followed by the word Ares at the very beginning of the definition, thus:

αρετη Αρης

And while I know most of you don't read Greek, it's easy to puzzle out.

The Greek letter A looks like our letter A in both upper and lower case.

The Greek letter R -- which is Rho -- looks like our letter P in both upper and lower case.

T -- looks like -- T.

While there are two Greek letters which have an "e" sound:

One is epsilon, which looks our letter E, and the other is eta, which in lower case looks like our lower case letter n.

And that's it.

αρετη = areté;

Αρης = Ares.

And there's an extremely strong relationship between the two, which Liddell and Scott make plain by putting the two words side by side:

αρετη Αρης

Are these the only two words which Liddell and Scott display in this way?

No.

They do it whenever they want to point out a strong relationship between words.

For example,

Mache -- [a] battle, fight, combat ; is paired with Machomai -- to fight, to fight with, ie, against ;

μαχη μαχομαι

and

Polemikos -- warlike, martial, skilled in war ; is paired with Polemos -- [a] battle, fight, war.

πολεμικος πολεμος

And clearly, in the latter case, the word Polemikos -- warlike -- derives from Polemos -- battle, fight, war.

Just as:

Areté -- Manhood, virtue, excellence, goodness -- derives from, is rooted in, Ares -- the Warrior God, the God of Battle, the God of Fight, the God of Manhood, the God of Fighting Manhood.

αρετη Αρης

Αρης is the root and the source -- of αρετη.

Which makes sense.

It makes sense that Ares, the God, the vast spiritual force, who both creates and empowers Fight and Manhood -- would be the root and the source of the human quality we call Fighting Manhood -- of areté -- of Manly Excellence, Valour, Prowess, Goodness, and Virtue.

So:

Areté -- Manhood -- which is valour, prowess, goodness, excellence, and virtue -- flows from Ares -- the God of War -- or, to be more precise, the God of Fight.

And if you click on the Latin -- that is, Roman -- word virtus, a word most often translated as Virtue -- this is what you see:

So:

The title of this article --

MANHOOD: A Reductional, Functional, Teleological, Incantational, and, above all, Sanctional

Lexicon --

may appear, at first glance, whimsical.

But you'll see that it's not.

That in the ancient Greek world, many very important words -- expressing what were literally the noblest ideas, concepts, beliefs, and ideals of the ancients, reduce to one word and one essence -- Manhood.

Fighting Manhood.

And that, consequently, we can say without question that the role of Manhood, functionally, teleologically, incantationally, and, above all, sanctionally, in giving form and substance to the Manly Warrior Kosmos of those ancient Men was -- as it still should be -- without equal.

So -- if we take any ancient Greek word in this Lexicon of Manhood, and reduce that word, if we strip away -- reduce to nothing -- all the non-ancient, extraneous, accretions of Christianized and heterosexualized fat that adhere to terms and concepts like nobility, honor, and moral beauty -- what's left is the lean and mean Manly Essence -- Manhood.

Moreover, when we rid ourselves of those pacific and effeminized accretions -- what we see is rough and tough -- Manhood.

Manhood:

Lean and Mean;

Ruff and Tuff.

For example: Consider the term "strife of valour," which we've much discussed, and which actually reads, in Xenophon's original, a strife or struggle -- about or for -- areté.

Once again, the translator, Marchant, writing ca 1925, says a strife of valour -- of areté -- and that's fine as far as it goes.

But what is areté?

"goodness, excellence, of any kind, esp. of manly qualities, manhood, valour, prowess"

Valour is the Man's Willingness to Fight;

Prowess is the Man's Ability to Fight.

And we can, therefore, think, per Liddell, of Valour and Prowess -- Willingness and Ability to Fight -- as the two constituent parts of Manhood.

Which means that areté is Fighting Spirit -- which is identical to Manly Spirit -- which is Manhood.

Fighting Manhood.

Fighting Manhood -- Virtuous Manhood, Goodly Manhood, Moral Manhood.

Now:

As I said in Death of an AIDS Activist, our contemporary conception of "masculinity" is sexual and hedonist -- but that of the ancients was NOT --

it was AGGRESSIVE and VIRTUOUS -- Manhood was the Man's Willingness and Ability to Fight -- Nobly and Heroically, for a Morally Just Cause.

Once that's understood, Xenophon's "erin [Strife] peri aretes [Manhood]" becomes a Struggle of, about, and for Manhood -- which is what it was:

περι -- see letter A, Roman numeral II: "of an object for or about which one struggles"

Again: Marchant's Strife of Valour becomes Xenophon's Struggle for and about -- Manhood.

And -- please try to understand -- it's not that Marchant is wrong;

It's that he was writing in 1925 -- when Valour and Manhood were far more closely identified -- far more closely -- than they are now.

Put differently:

Manhood in 1925 was still understood to be Fighting Manhood.

So -- and again:

Our heterosexualized culture defines gender -- masculine or feminine -- on the basis of sexual desire.

NO OTHER CULTURE has EVER defined gender in that way.

The Greeks have a word -- ho arren -- the Male, Maleness, or being Male -- which is virtually synonymous with andreia -- Manliness, Manhood, Manly Spirit ;

and that in turn is defined as the Male's Willingness and Ability to Fight.

So:

Reductional means that we reduce the word, we strip the word, to its ESSENTIAL meaning -- which, as you'll see, is always -- MANHOOD.

BIBLION PROTON

By Bill Weintraub

Οur Lexicon of Reductional, Functional, Sanctional, and Incantational Manhood contains both ancient Greek and contemporary English words.

We'll start with the ancient Greek words themselves, presented with links to their definitions in Liddell and Scott's Ancient Greek Lexicon.

And please note that if the definition you see in the link differs, slightly, from that on our page, it's because I'm using the definition given by Liddell and Scott in a 1909 print edition which I use.

But most of the time the print edition of 1909 and the online edition, some of which is dated 1889, and some of which comes from a revision published in 1940 -- agree.

Here's our Lexicon of Manhood, starting with "The Alphas of Male" -- the Alphas of Manhood, Manliness, and Manly Spirit.

Agapenor : loving manliness, manly

Agapenor is a foundational word among the Greeks, it goes all the way back to the Iliad, which is often described as the ancient Greek Bible, and it refers to Heroes and Warriors who both love Manliness -- and are themselves Manly.

MANLY MEN LOVING MANLINESS.

MANLY MEN LOVING MANHOOD.

So -- Many Christians are familiar with the Greek word -- agape (αγαπη)-- meaning "spiritual love."

But, that word, agape, in Greek, has many forms.

Such as

agapetikos (αγαπητικος)

meaning "disposed to love, affectionate";

And

agapetos (αγαπητος)

meaning "dearly beloved, worthy of love";

and Agapenor (αγαπηνωρ)

meaning "loving manliness, manly."

If you're a Christian, you should be aware that agapenor -- "loving manliness, manly" -- is just as much part of your heritage and your birthright -- as agape.

And regardless of your religious faith, you should realize the implications of agapenor -- "loving manliness, manly" -- which applies to Warriors and Heroes -- and which are profound.

ανδρειος

And guys, andreios can become a noun, "to [the] andreion," which then means Manhood, Manliness, Virility

andrikos hydros (ανδρικος ιδρως) = the sweat of manly toil

Areté, one of the most important words in the Greek language, corresponds to the Latin Virtus, which is defined as Manhood, manliness, strength, vigor, bravery, courage, excellence; Valour, gallantry, fortitude; and as Goodness, moral perfection, high character, virtue; Worth, merit, value.

This definition of the Latin word Virtus-- and guys, I cannot emphasize this strongly enough -- applies equally to the Greek word Areté:

In sum, Manhood, Valour, Goodness, Virtue, Worth -- Excellence.

Manhood is Valour, Manhood is Goodness, Manhood is Virtue, Manhood is Worth -- Manhood is Excellence.

Agathos means "good," and I'm putting it here, out of alphabetical order, because it's the adjectival form of the noun Areté --

and cannot be understood without reference to Areté.

So:

To the ancient Greek mind, when someone or something is described as "good," the description carries all these other meanings --

with it.

So -- a Man who's Good -- is, because of his possession of his Manhood -- Manly, he's strong, vigorous, brave, courageous, and excellent; he's valorous and gallant; he displays goodness and moral perfection, and has worth, value, and merit.

And !!! --

There are the comparative and superlative forms of the word "good" -- in English, "better" and "best."

So, and just in case you've forgotten your grade school grammar --

Normally, in Greek as in English, there's the adjective -- eg, strong; and to get the comparative and superlative, a suffix is added -- strong-er, strong-est:

Strong, stronger, strongest.

Brave, braver, bravest.

But with the word Good, and in English -- the word changes in the comparative and superlative -- to better and best.

So -- it's not good, good-er, good-est -- it's Good, Better, Best.

And the same is true in ancient Greek.

There's Agathos = Good.

But the comparative and superlative are different.

Now: I've frequently cited Liddell and Scott, thus:

That's from my print copy of Liddell and Scott, which was originally published in 1909.

But, you'll notice, I have an ellipsis in there.

Here's how it reads without the ellipsis:

So -- Ares is not only the root for areté -- excellence, goodness, virtue, Manhood;

Ares, the Warrior God, the God of Manhood, the God of Fight, and the God of Fighting Manhood -- is also the "root" -- the source -- for all that is areion, better; and aristos -- best:

To be better, stouter, stronger, braver, more excellent, and mightier -- is to be more manly.

Which means that in Greek, the Men who's Best is the Man who has the most Manhood and is therefore the most Manly, the strongest, most vigorous, bravest, most courageous, and most excellent; he's the most valorous and gallant; and he possesses the most goodness, moral perfection, worth, value, and merit.

~Arrian, The Campaigns of Alexander, translated by Aubrey de Selincourt

And then there's the prefix "ari-" cited by Liddell:

So -- The prefix ari- confers the sense of best, strongest, bravest, and most excellent, as in these words:

ο αριστευς

And if you look at Roman numeral 3, you'll see aristeueske machesthai (αριστευεσκε μαχεσθαι) = he was best at fighting

αριστοκρατια

αριστομαχος

And guys, in the online link, Liddell and Scott define aristeia as excellence, prowess; but in print they say "the feats of the hero that win the mead of valour ; any great, heroic action"

And they give the example, from the Iliad, of "Diomedes' Aristeia" --

which we could translate as Diomedes' Heroic Deeds

-- but an equally valid definition really and truly is heroism, including moral heroism.

Classicist Werner Jaeger, for example, speaks of

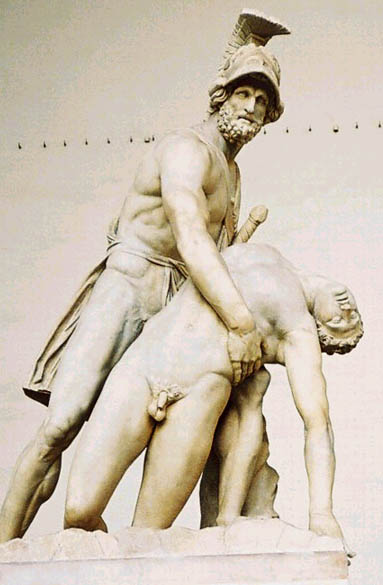

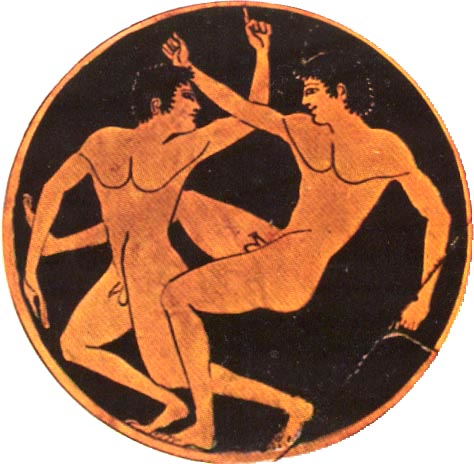

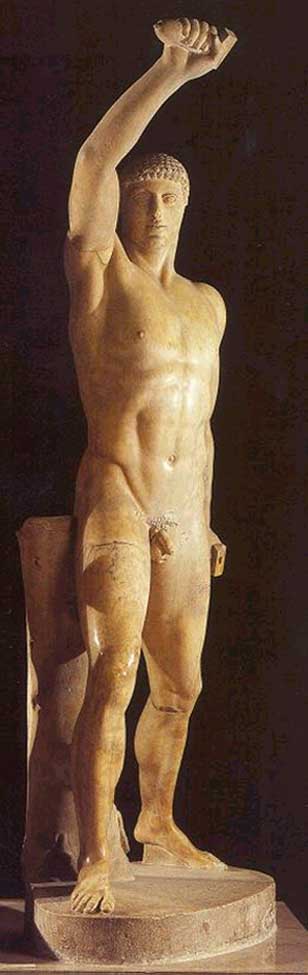

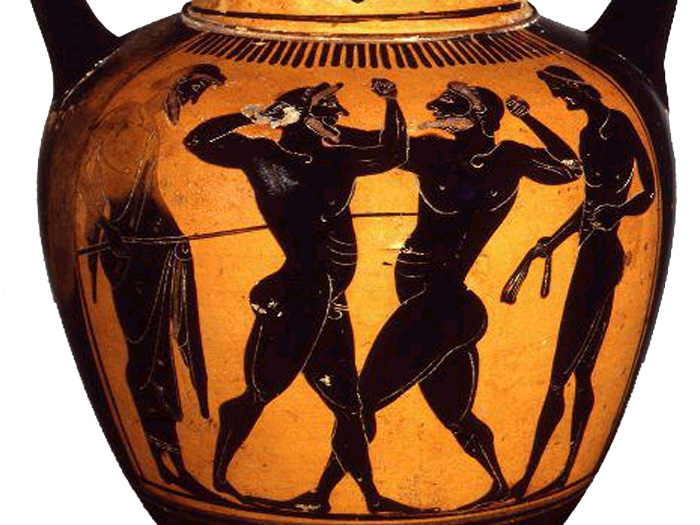

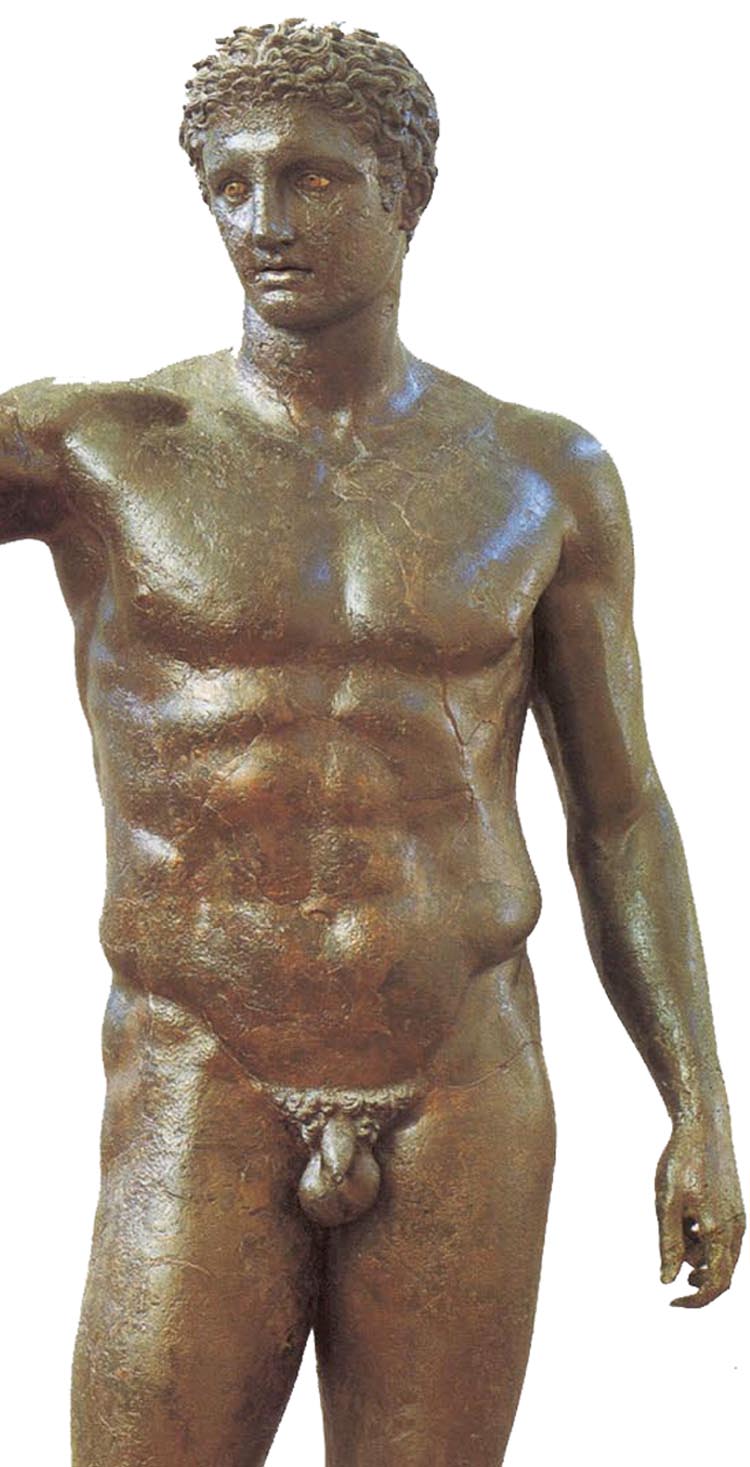

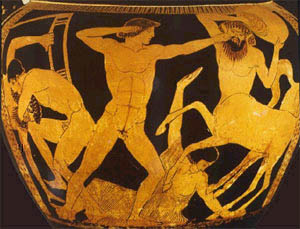

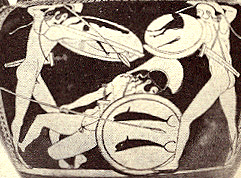

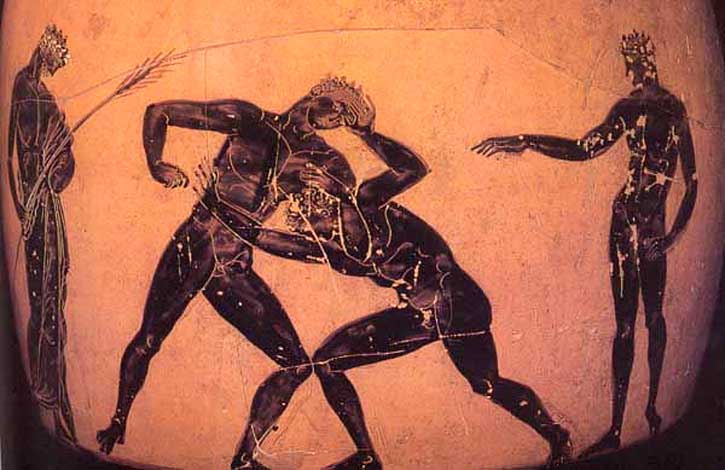

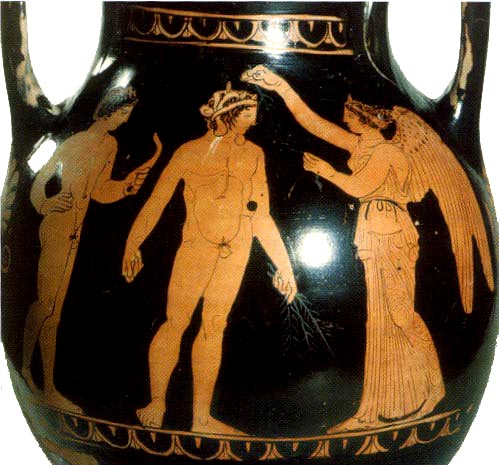

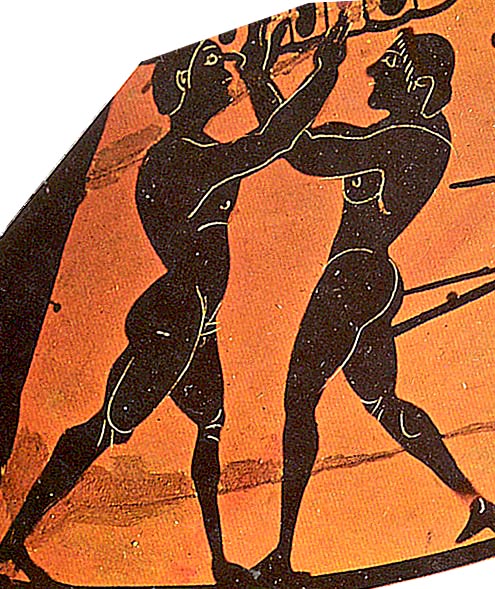

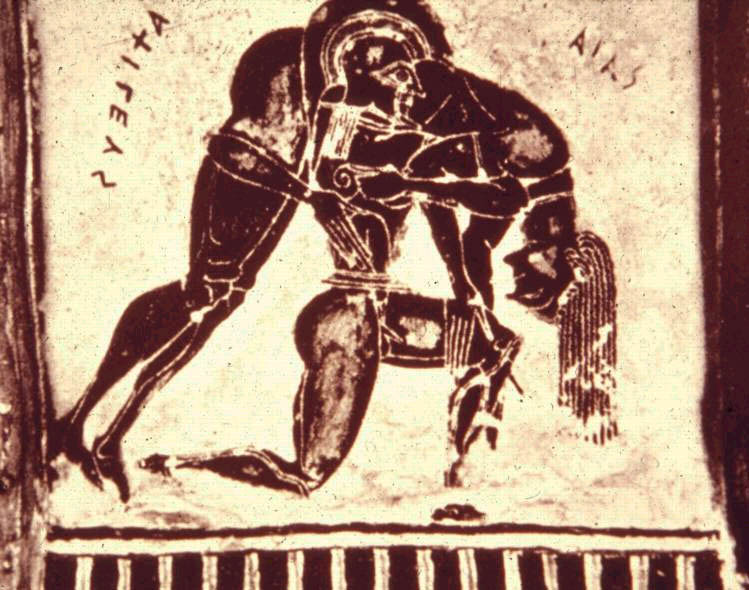

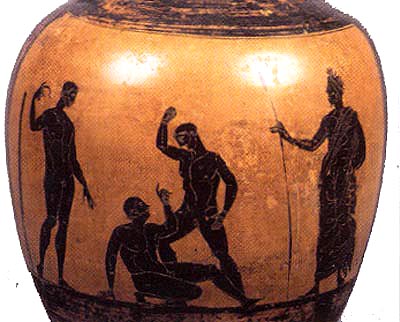

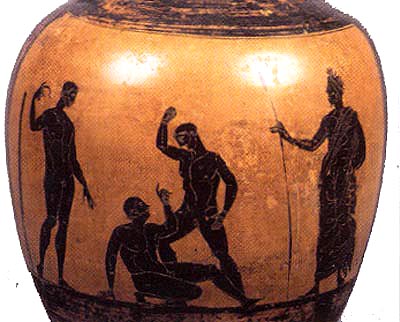

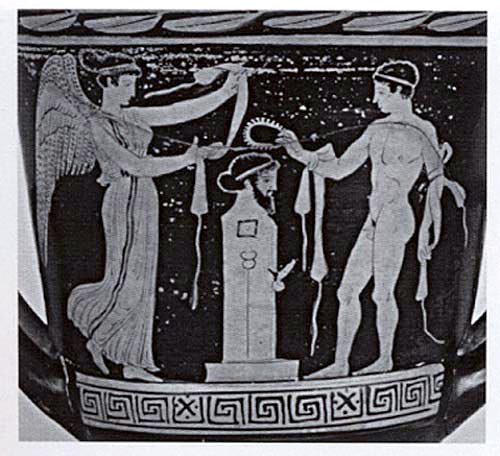

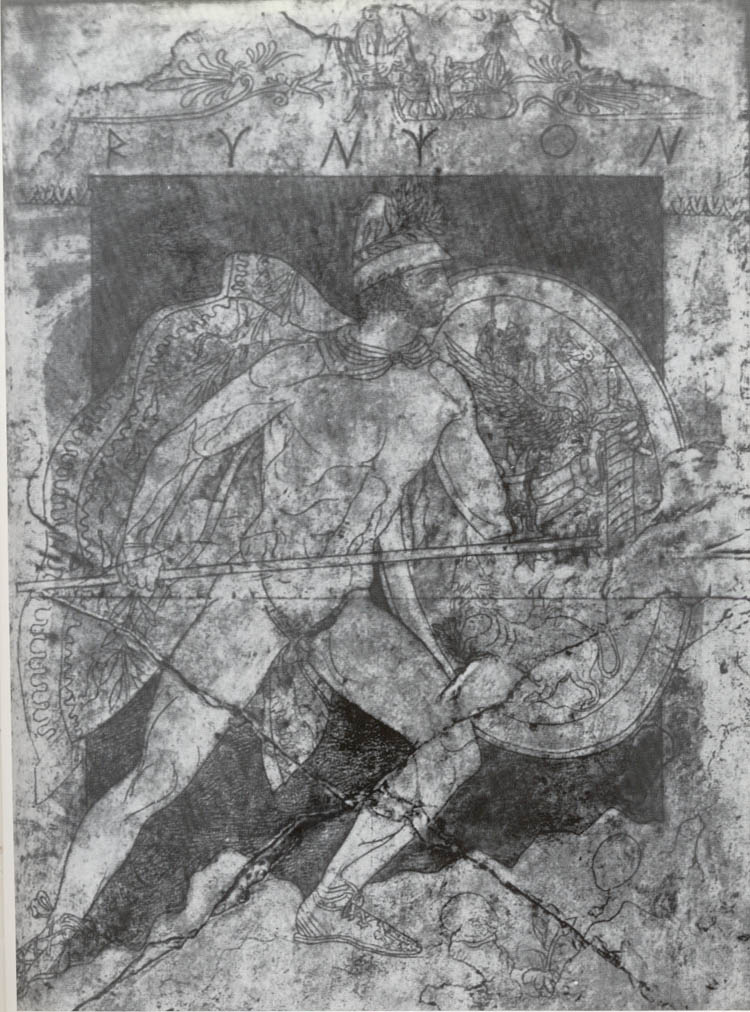

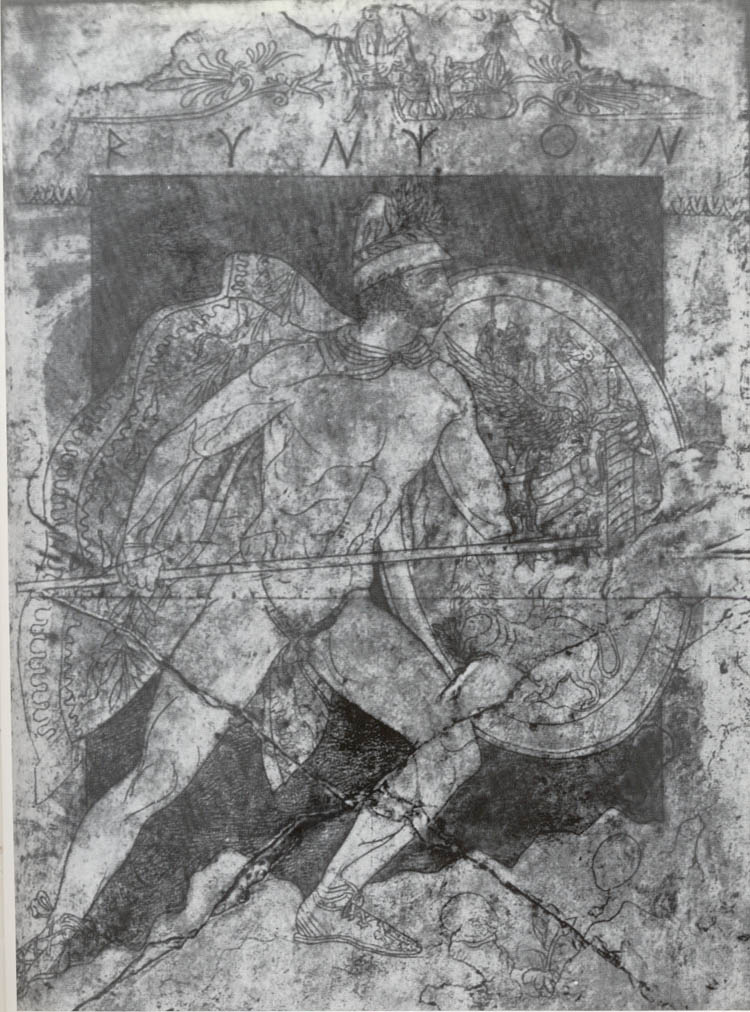

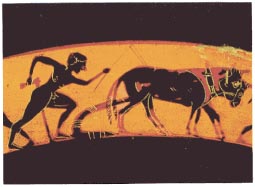

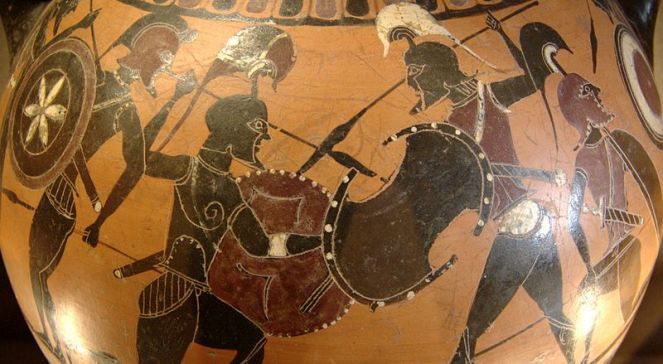

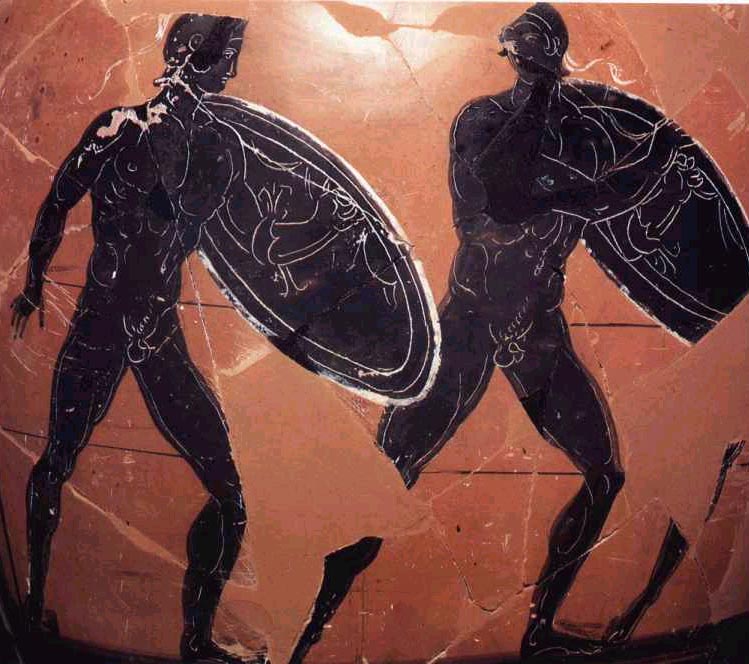

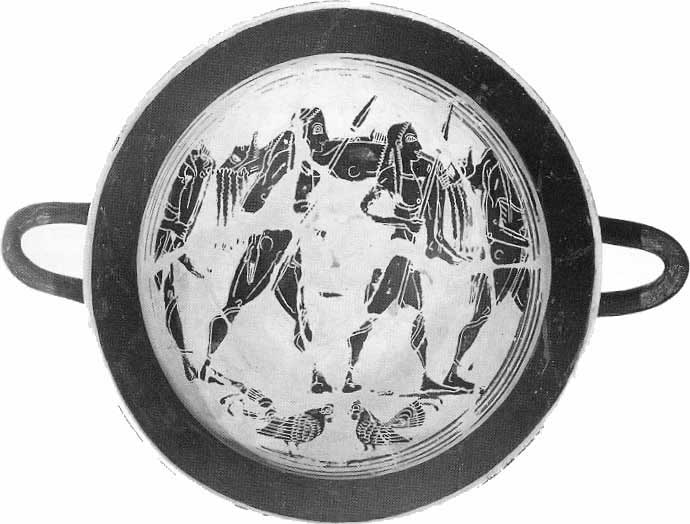

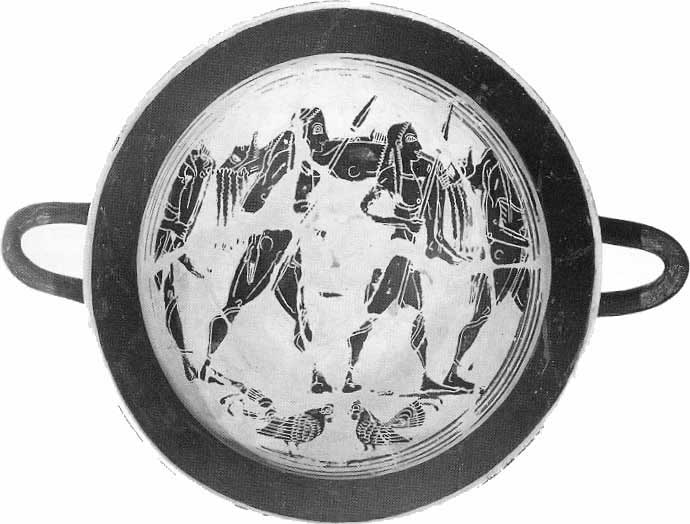

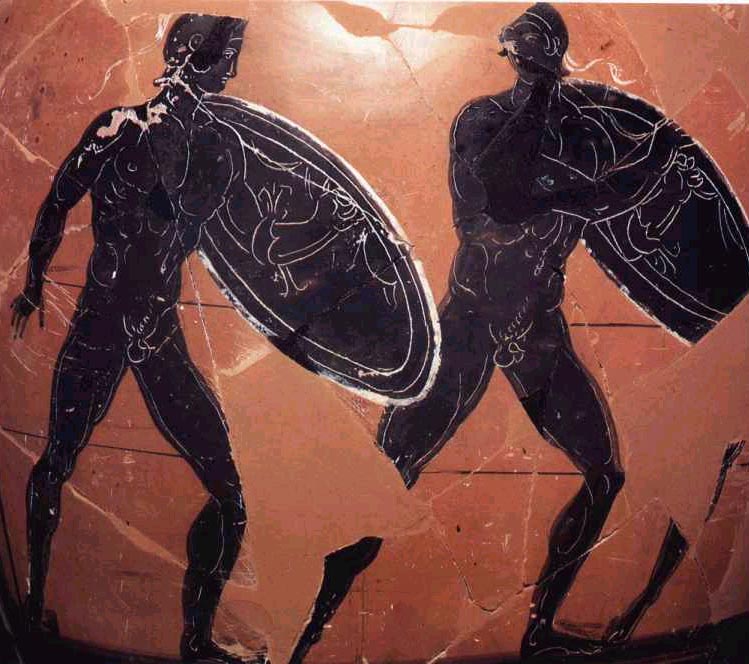

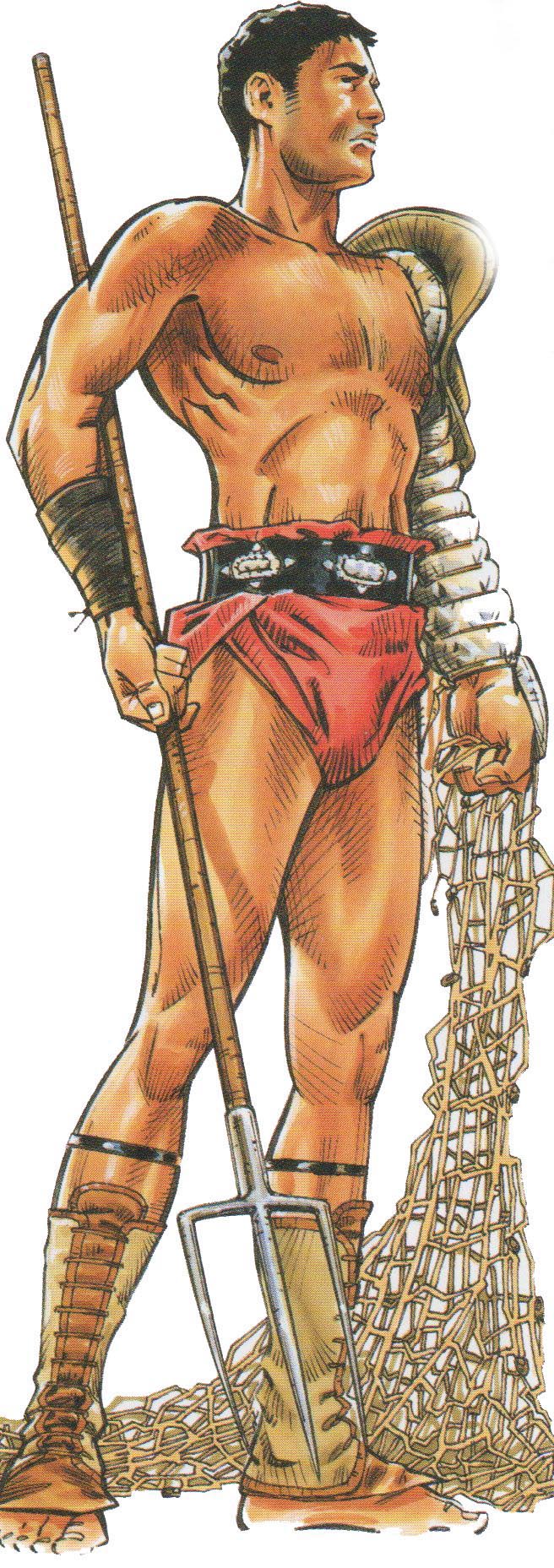

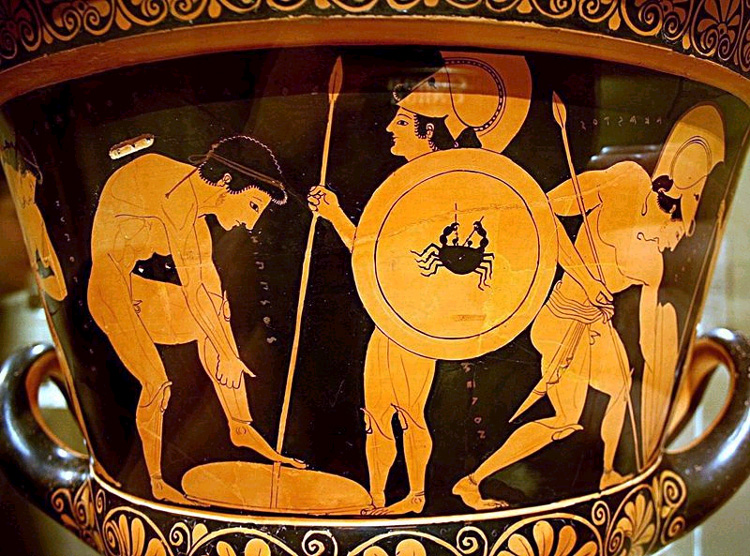

So -- in this vase painting, Achilles is demonstrating aristeia -- moral heroism ; and "taking possession of the beautiful":

And, guys, we'll be getting to the term "the beautiful" -- to kalon -- in a bit.

For now, let's stick with the adjective agathos, meaning "good," because not only is there an And!!! in the form of areion (better) and aristos (best) and all the other ari- words --

But there's also a --

Plus !!! --

Because the adjective agathos becomes a noun in its own right -- agathon; and -- and this is important, guys -- as to agathon -- "the good" -- or just tagathon, when used by Plato it becomes the Good -- in Latin, the Summum Bonum, the Supreme Good:

And you can find those words if you look at the definition of αγαθος and look for Roman numeral II, then Arabic numeral 2.

And, here, as just a little extra-added plus, a bonus, we might say, is the Latin word for good:

And if you click on that link and use your browser's "find" function to look for summum, you'll see the chief good, end of being, by which is meant -- the Purpose of Life.

So a bonus is kinda like a boner -- isn't it?

Because it contains within it -- the Purpose and Source of Life.

But that's getting us into something known as "Plato's Idea of Good," and you needn't worry about that -- for now.

Just understand that the Greek word for "good" -- agathos -- and indeed, the Supreme Good, the very Purpose of Being itself -- refers back and ultimately reduces to -- MANHOOD.

That's what it does.

And, guys, I'm just getting started.

Lots more to come:

αρρατος

Notice that arren is the equivalent of the Latin word mas, meaning masculine, manly, brave.

And that arren-the-adjective can, with the addition of "to" -- the -- become "to arren," the noun -- meaning Manhood, Manliness, Virility, Strength.

And that's just Warrior Culture and Warrior Kosmos 101 -- the Masculine Man is Manly, the Manly Man is Brave, the Brave Man exhibits and demonstrates that Manly Bravery -- that Brave Beauty -- in Fighting.

Fighting Manhood.

So guys, we started with the words agape -- love -- and andros -- Man.

And we saw that agape combined with an archaic form of the word Man becomes agapenor -- Loving Manliness, Manly.

And that from andros itself comes andreia -- Manhood, Manliness, Manly Spirit ; while andros combined with the adjectival form of areté -- that is, agathos -- becomes andragathia -- Manly Goodness, Manly Excellence.

Notice how positive, and indeed not just positive, but exuberant, all these words are.

And we saw too that there are a host of other words associated with and derived from andros, including andrei-oma -- Manly Effort; andreiuo -- to fill with Courage, with Manhood; andrikos -- Masculine and Manly, like a Man; andrizo -- make a Man of, make Manly; androdes -- like a Man, Manly; and andron -- Men's Mess, Dining Hall, Quarters.

And here too we can see how positive and indeed exuberant all these words are -- Manly Effort, to Fill with Courage and Manhood, to be Masculine and Manly, to make a Man of, to make Manly, like a Man, Manly -- even the Andron, the Men's Mess, has very positive associations for the Greeks.

Not least because along with the palaistrai / gymnasia,

it's the locus and focus of Male Love.

And if we then turn from the words associated with agape and andros -- Man -- and simply look at just some of the words directly derived from or referring back to -- ARES -- the God of Fight and Manhood, the Personification of Fighting and Fighting Manhood -- we get a very long list, all of which, again, are not just positives, but superlatives:

All of these words refer or relate directly to Virtue, Goodness, and Manhood, and all of them are, therefore, Moral; and all reference these highly-valued moral attributes:

BIBLION PROTON

By Bill Weintraub

Αnd now guys, our Lexicon starts to become really interesting.

m

Because we're leaving the Alphas -- if not the Alpha Males -- and looking at three really fascinating -- and reductional -- Greek words:

Kalon -- Moral Beauty;

Orthos -- Standing Erect; and

Timé -- the Worth which accrues to a Man through Prowess in Battle.

The first and last of these -- kalon and timé -- are often -- not always, but often -- translated, particularly by scholars like Benjamin Jowett, who lived in the nineteenth century, and Paul Shorey, who was born in 1857 and died in 1934 -- as "honor."

But our own sense of the word "honor" is so etiolated compared to theirs -- that the word virtually always, nowadays, needs to be elucidated.

For example, both Jowett and Shorey studied, in the nineteenth century, in German universities in which dueling was common among the students.

And as late as the 1920s, when Shorey was still alive, dueling to settle "affairs of honor" was still common among the German officer corps -- a German chief of staff was cashiered by the Weimar Republic because he tried to regulate that dueling.

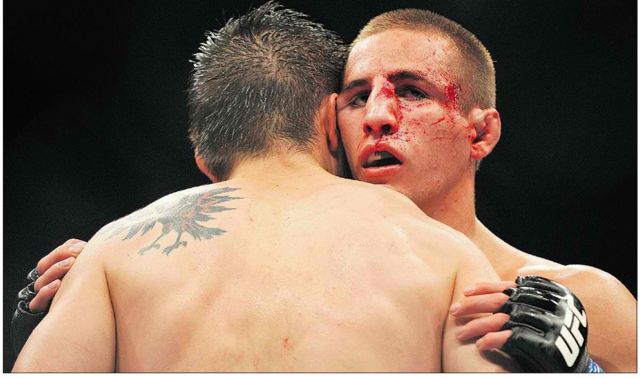

This picture shows a fresh wound and older scars on the face of a nineteenth-century German student.

Such scars, which were common, should be understood as analogous to -- I didn't the say the same as, but analogous to -- the "crinkled" or "cauliflower" ears sported by Spartans and pro-Spartan Greeks who had engaged in boxing and pankration, and which were notorious in ancient Greece.

Indeed, there are not one but two references in Plato to the "battered" or "broken" ears of the Spartans and those in the pro-Spartan factions:

~Plat. Prot. 342b,c, translated by Lamb.

Is Sokrates telling the truth?

Do "some get broken ears by imitating [the Spartans], bind their knuckles with thongs, [and] go in for muscular exercises [gymnastika -- nude training]"?

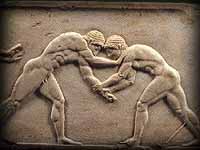

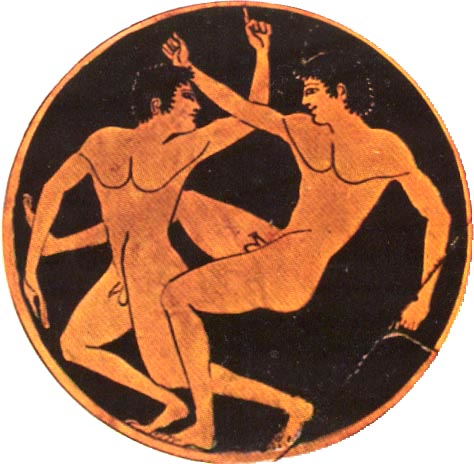

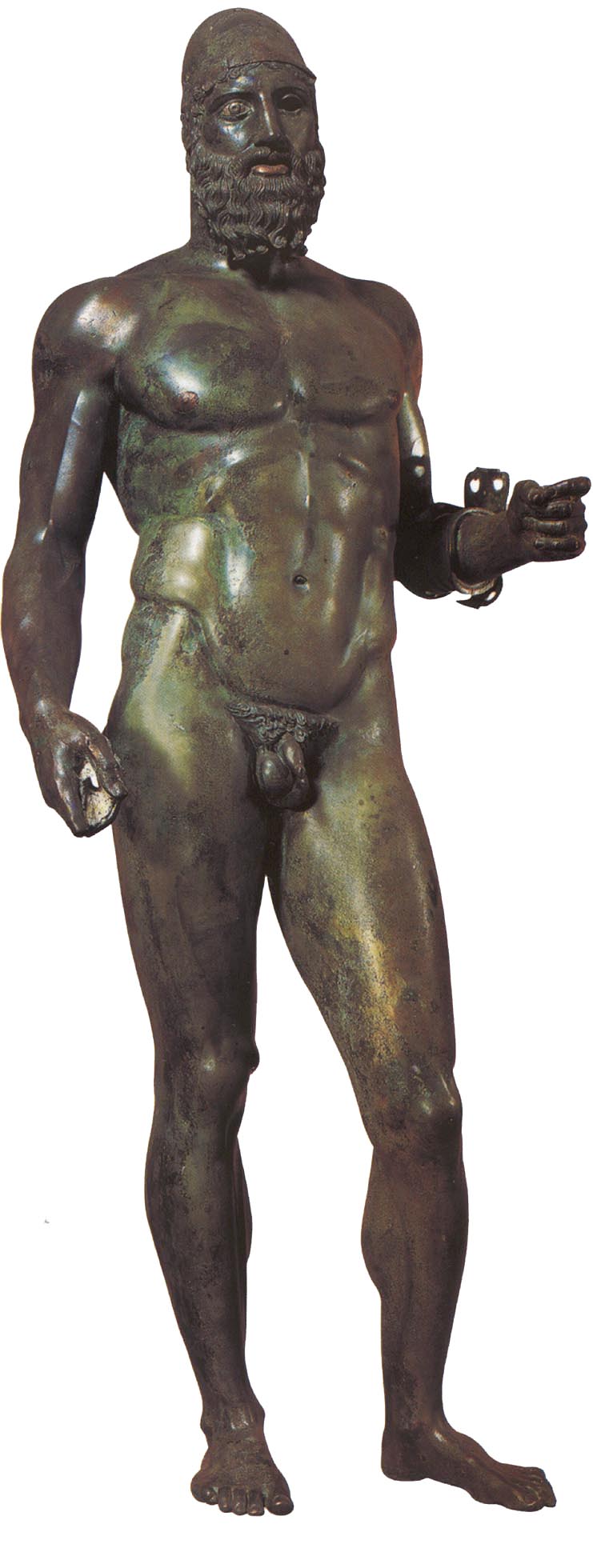

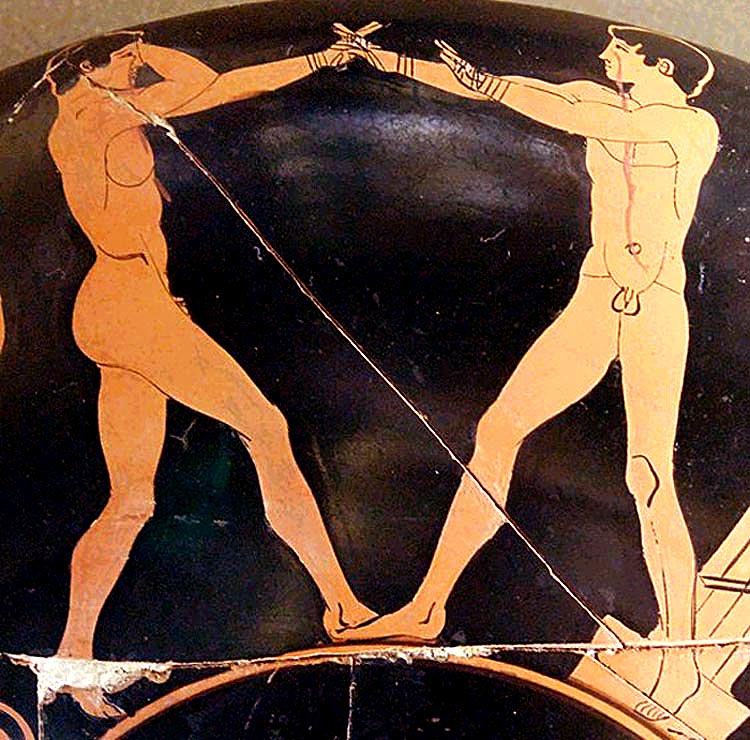

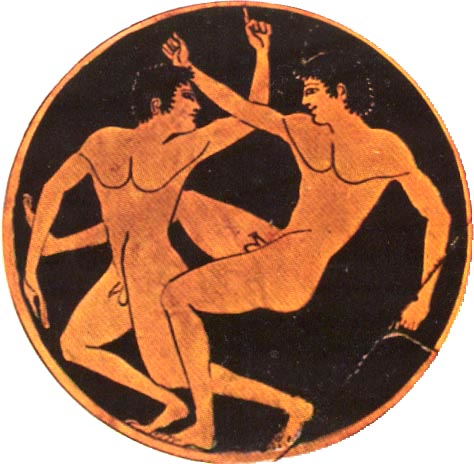

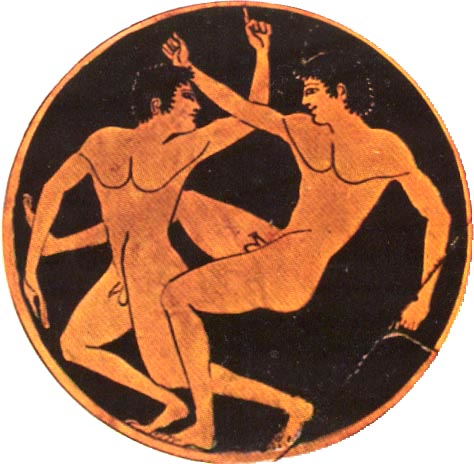

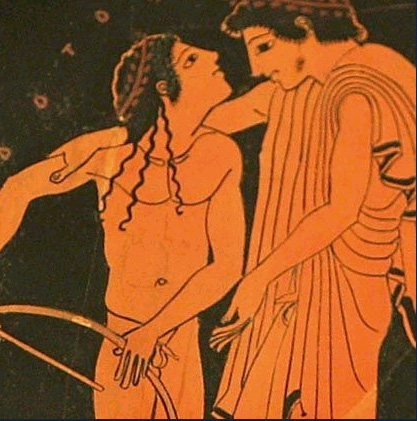

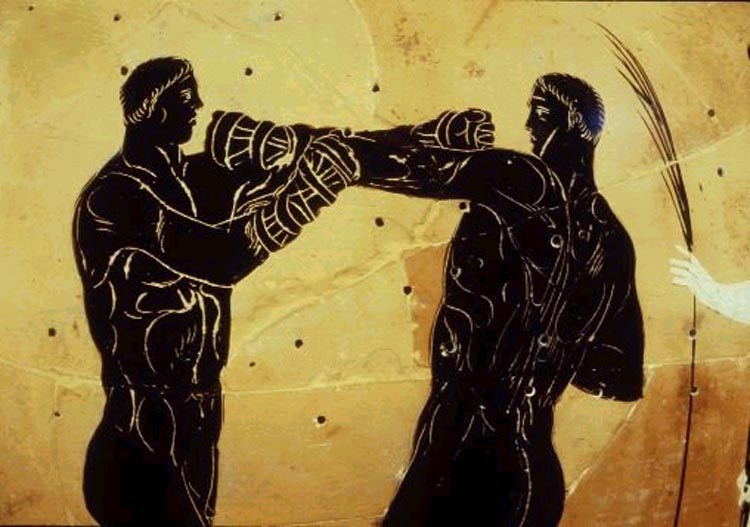

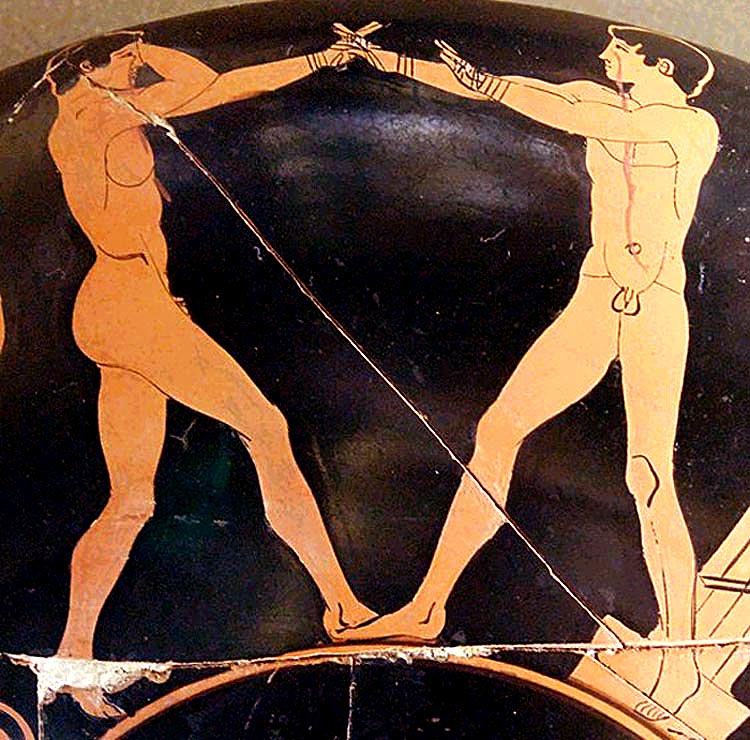

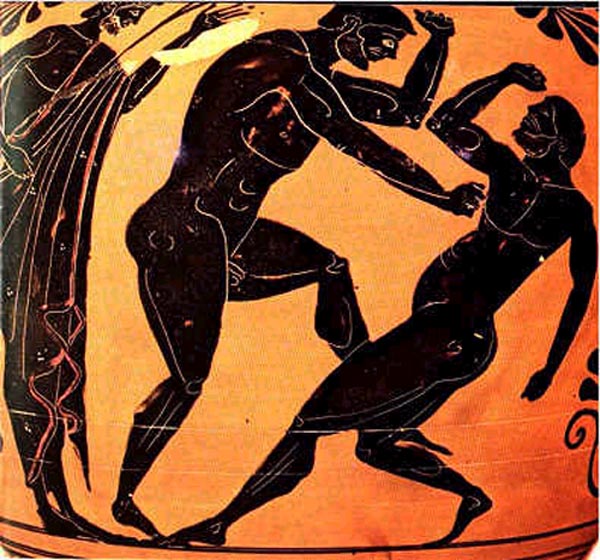

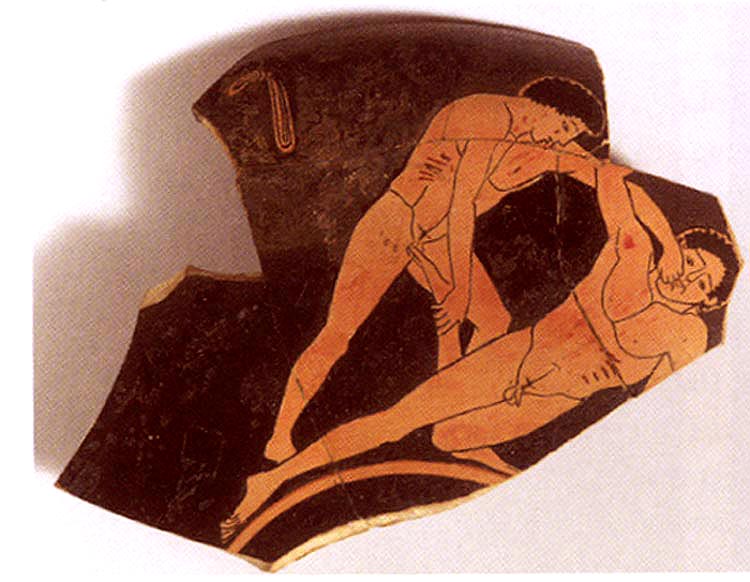

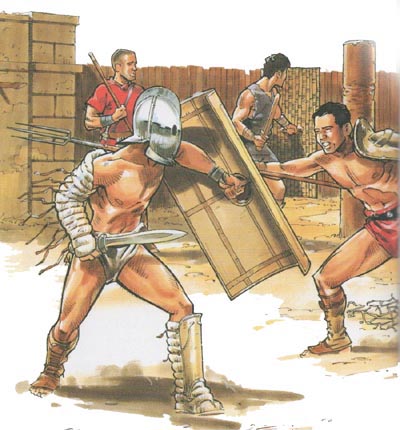

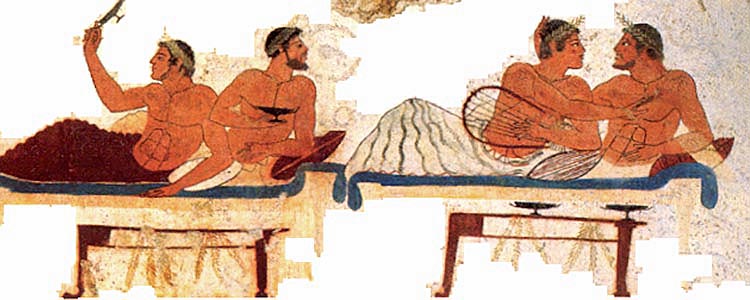

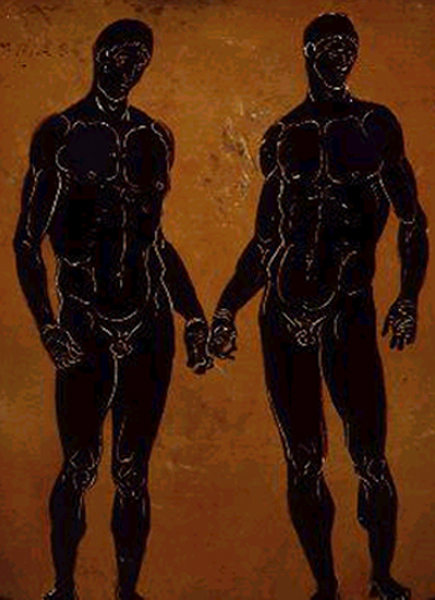

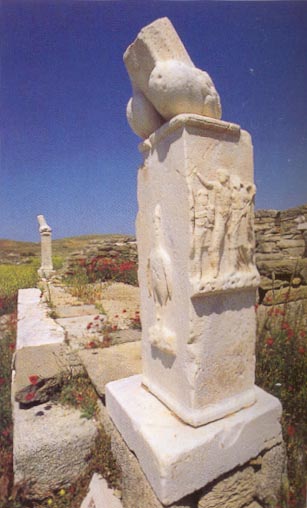

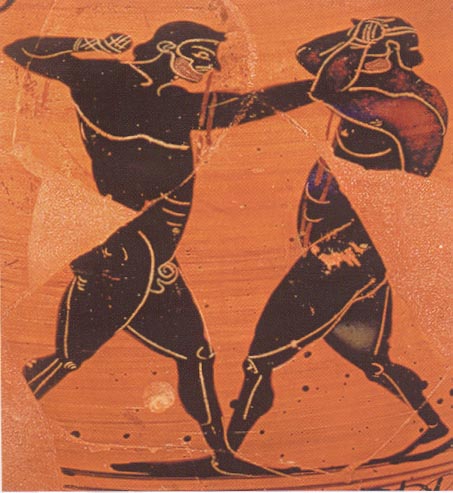

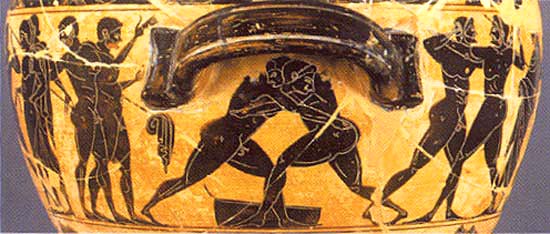

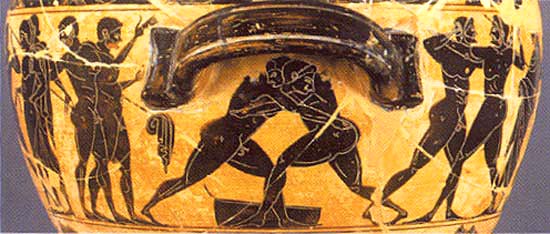

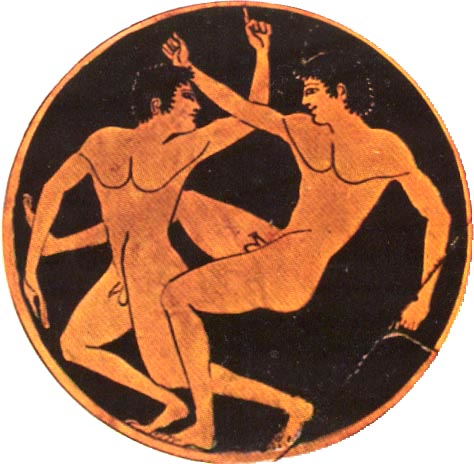

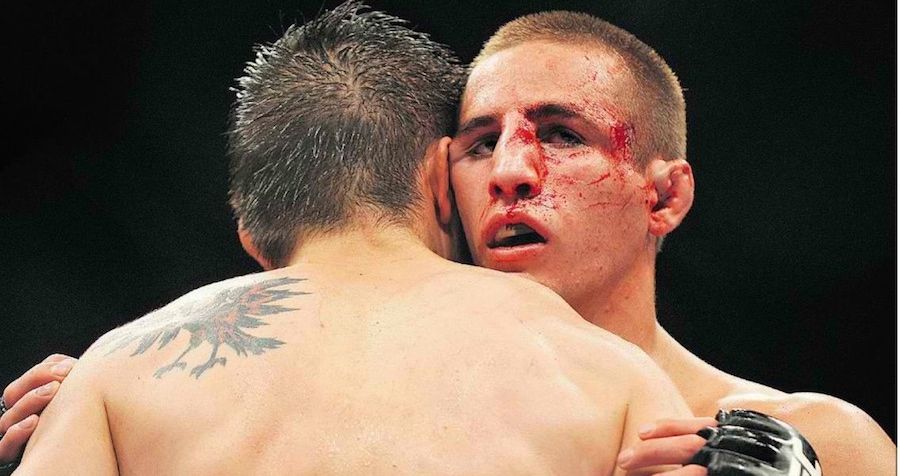

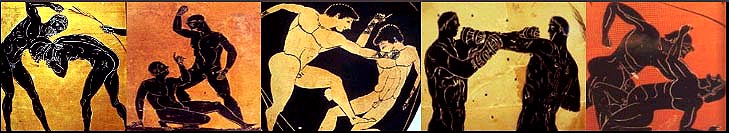

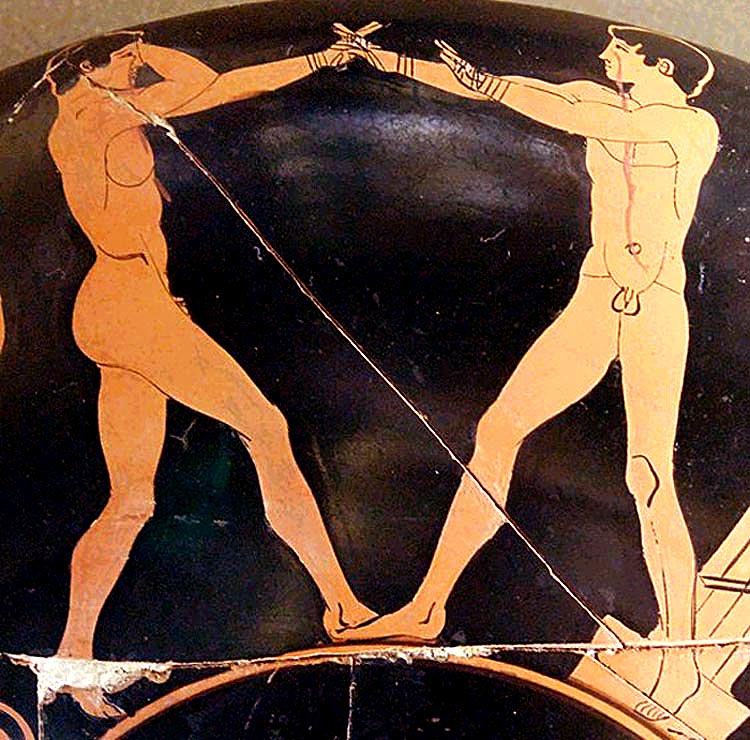

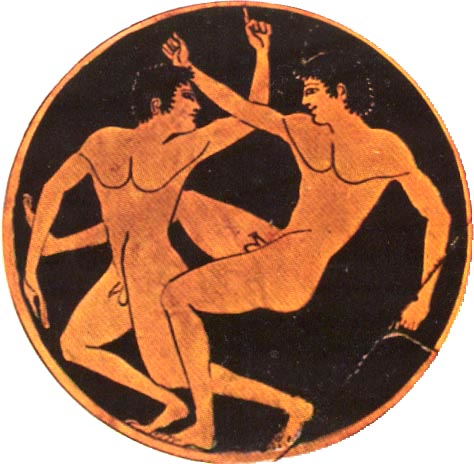

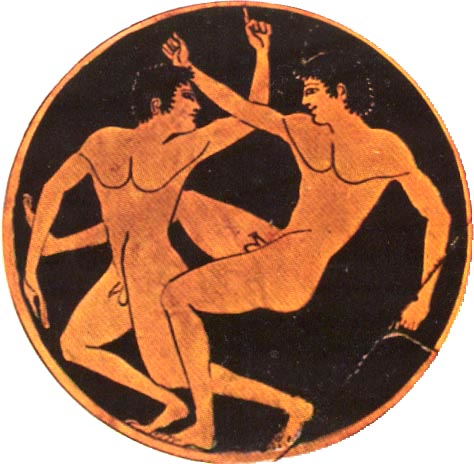

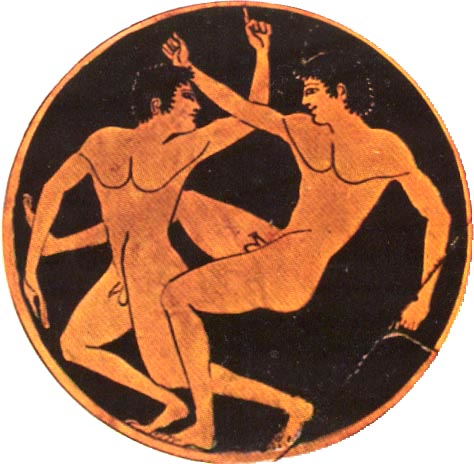

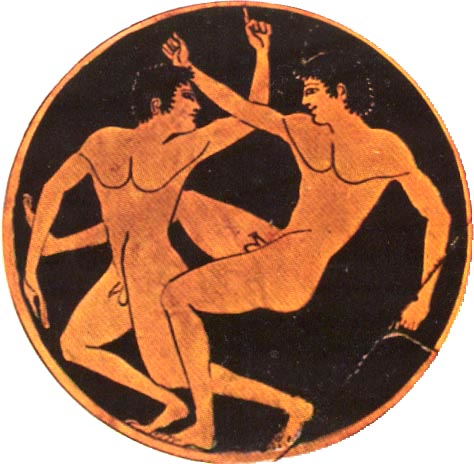

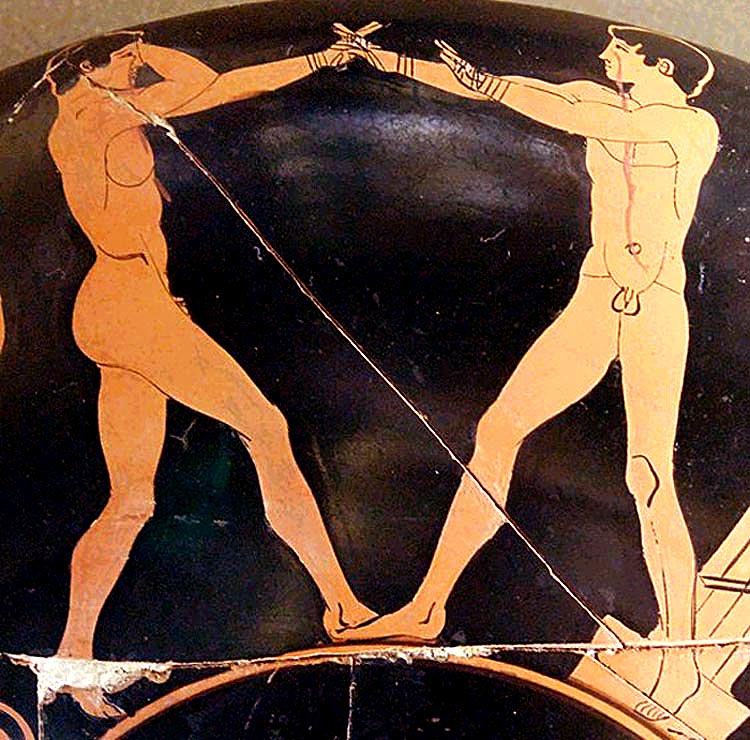

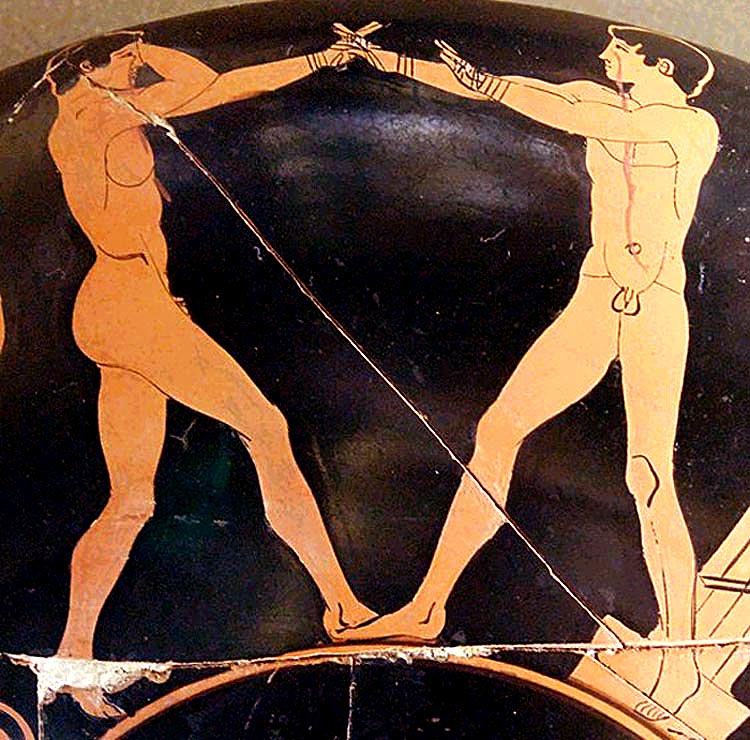

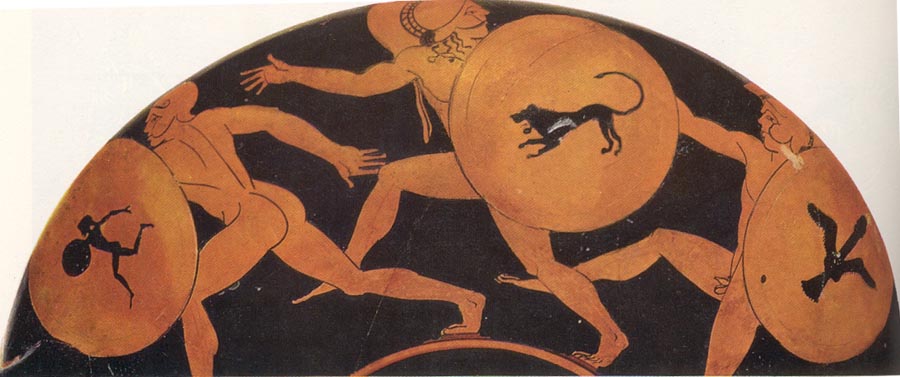

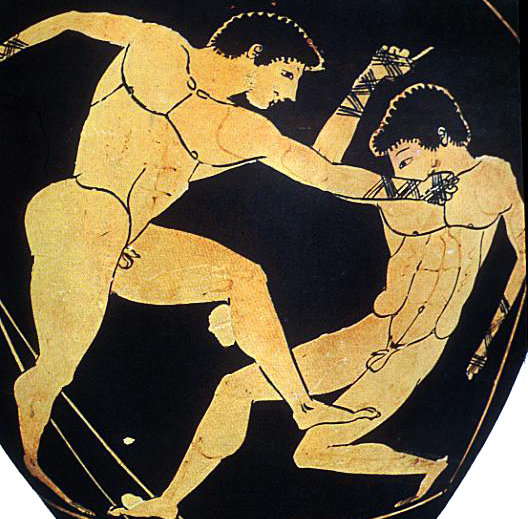

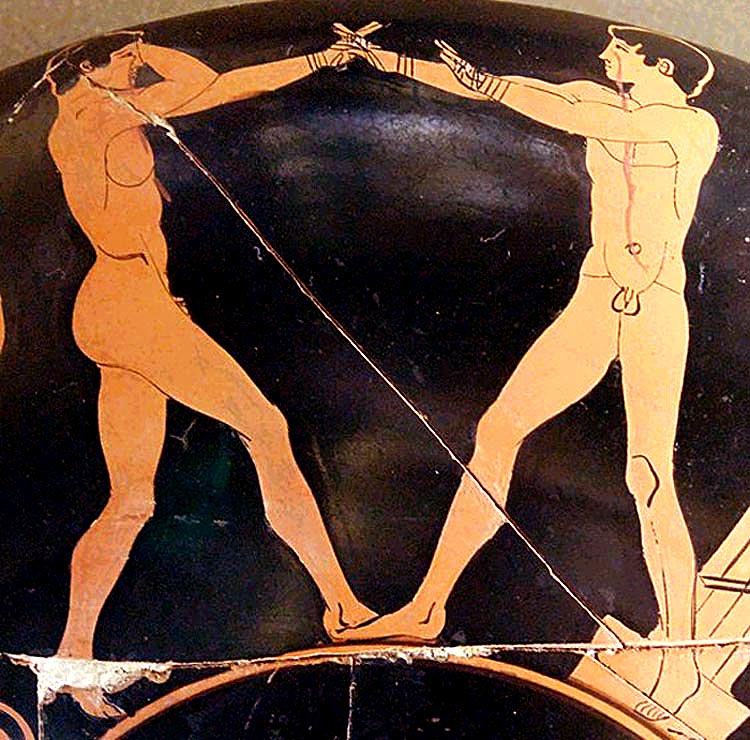

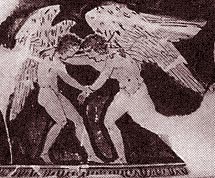

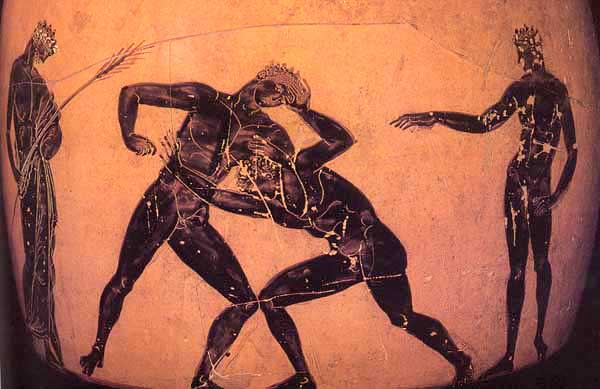

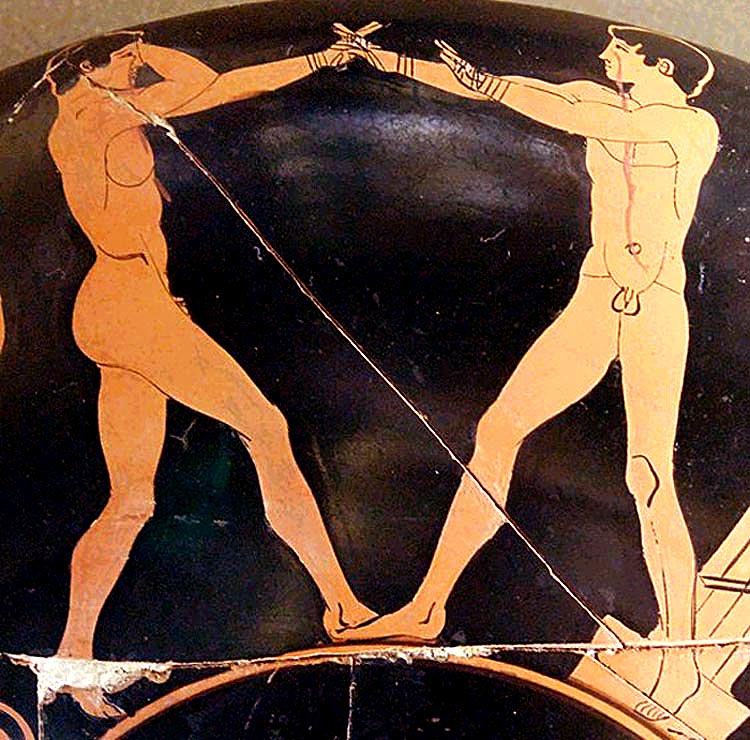

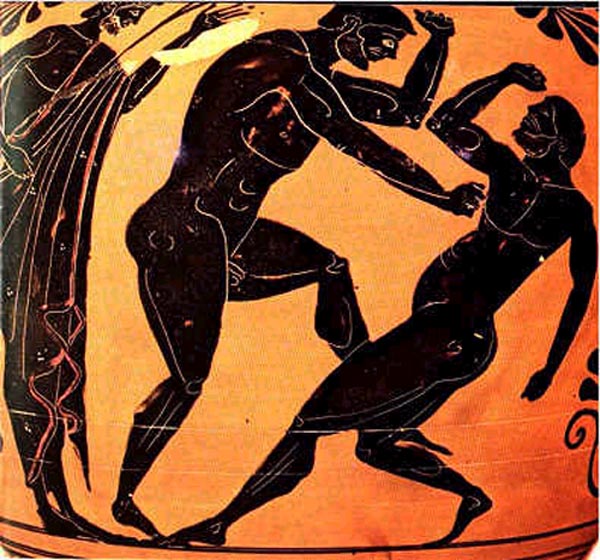

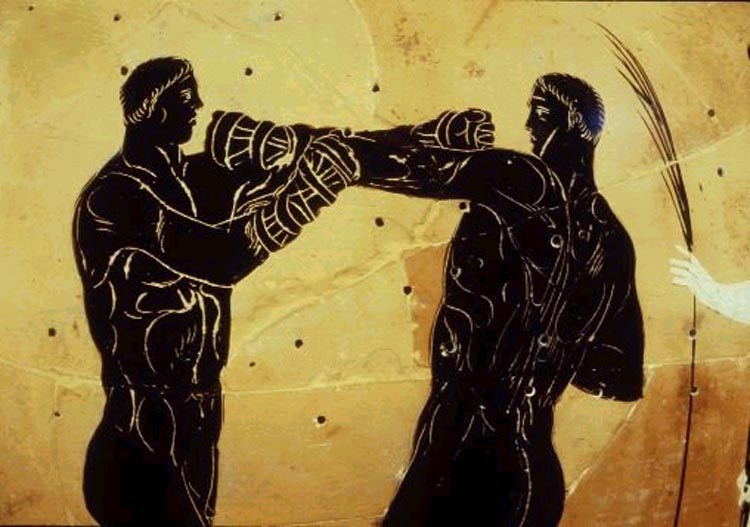

Well, here's a pic:

The boxers have indeed bound their knuckles with soft leather thongs, and are Fighting Nude.

Are their ears "broken"?

They appear so to me, but I don't know if that's what the artist intended.

But -- his ancient viewers would have known what he meant to represent.

Moreover, notice that Sokrates says that the Spartans owe their superiority to Fighting --

-- and --

Valour -- and the word translated as Valour is -- Andreia --

-- Manhood!

The Spartans owe their superiority to Fighting and Manhood --

that's what Sokrates actually says.

He says Machomai kai Andreia -- Fighting and Manhood.

That link is ever-present for the Greeks.

And here's another reference to battered ears, also in Plato:

Callicles

~Plat. Gorg. 515e, translated by Lamb.

So our old friend, the hedonist Callicles, doesn't like "the folk with battered ears."

And there's a footnote, [2], in which the translator explains that "the folk with battered ears" are

Of course, I wouldn't call boxing an addiction, but that's okay -- what Prof Lamb makes clear is that Sparta and the pro-Spartan Greeks -- were heavily into boxing.

So, and like I said -- and don't you like the way I back up what I say with references and citations?

I hope so.

Because, you know, I have opponents who lie about me, slander me, on the web, and they never cite anything --

they just say the first or second fool thing that comes into their head, and then hide behind their "internet anonymity."

I don't do that.

I post under my own, real, name -- and cite my sources.

You would think that would give me more credibility than my anonymous opponents, but my sense of the vast majority of people who use the internet, including the vast majority of the males who visit this site -- is that they're just not able, they just don't have sufficient intellect or discriminatory power or just plain common sense, to tell the difference between a man named Bill Weintraub -- and some creature calling itself "anonymous."

But there is a difference -- a HUGE difference -- and you need to figure that out.

So, and like I said, and with cited sources, "crinkled" or "battered" or "broken" or "cauliflower" ears were sported by Spartans and pro-Spartan Greeks who had engaged in boxing and pankration, and for that reason were notorious in ancient Greece.

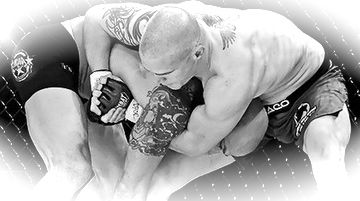

And they're still common today:

These battered ears were and are badges -- ikons, says Plutarch -- of Manhood -- of the Man's Willingness and Ability to Fight.

One anthropologist quoted by classicist JE Lendon in a 1995 article, and which I'll discuss in a forthcoming post, says that "the ultimate vindication of honour lies in physical violence."

By "physical violence," the anthropologist means -- Fighting.

While honour is clearly -- Manhood.

Which you can plainly see:

Which classicist Jaeger terms the Man's "natural instinct for self-assertion."

And that's what it is.

Scholars like Jowett and Shorey who were born and had lived in the nineteenth century would have understood, viscerally, that the word "honour" was inextricably connected to the Manly ideas and ideals of terms such as "Moral Beauty" and "Manhood."

As is Fighting.

Fighting is inextricably intertwined with Moral Beauty, Virtue, Goodness, and Manhood.

The Greeks understood that.

As you can see when Sokrates speaks directly of Machomai kai Andreia -- Fighting and Manhood.

The Greeks understood that Fighting and Manhood are inextricably intertwined.

They understood that Fighting is inextricably intertwined with Moral Beauty, Virtue, Goodness, and Manhood.

The Greeks understood that.

Most nineteenth-century Men, including scholars like Jowett and Shorey, understood it.

We don't.

We don't -- most of us -- understand a concept like Honour -- or Fighting itself.

So both need to be explained:

"noble and beautiful"

The word "beautiful" in ancient Greek carries with it the sense of Nobility, of Virtue, of Manhood; and "Nobility" in particular means, more often than not, "selflessness."

Again, and this is very important: Nobility, more often than not, means selflessness.

It doesn't mean the House of Lords or guys running around in ermine robes.

It means selflessness.

Which leads to our next word and its definition:

First of all, to find that meaning of moral beauty in the Greek definition, look under Roman numeral III, Arabic numeral 2.

This is the *moral* beauty which Jaeger is talking about when he says:

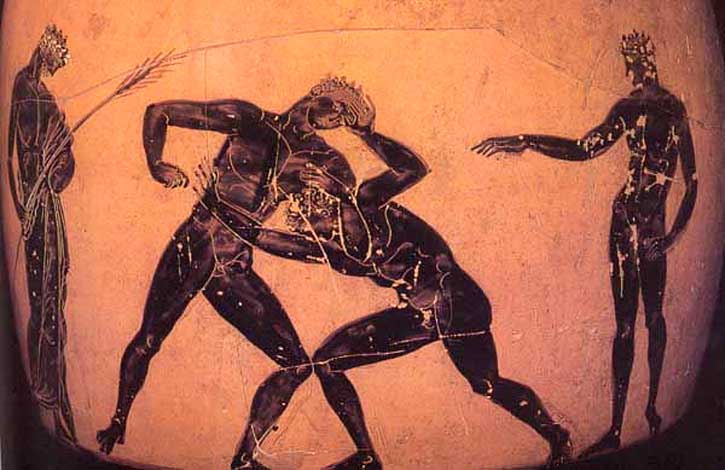

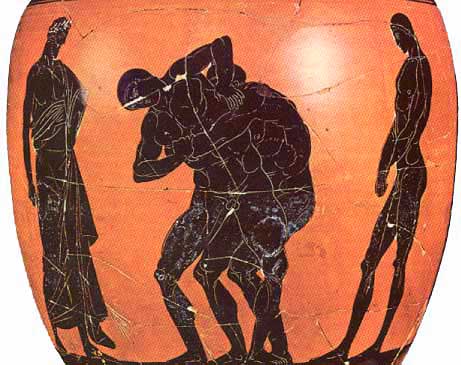

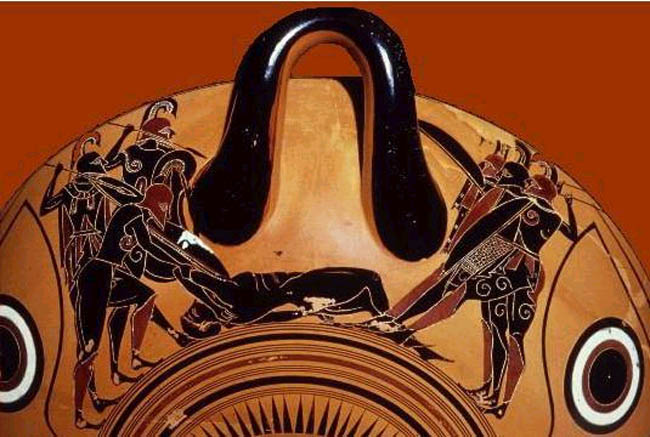

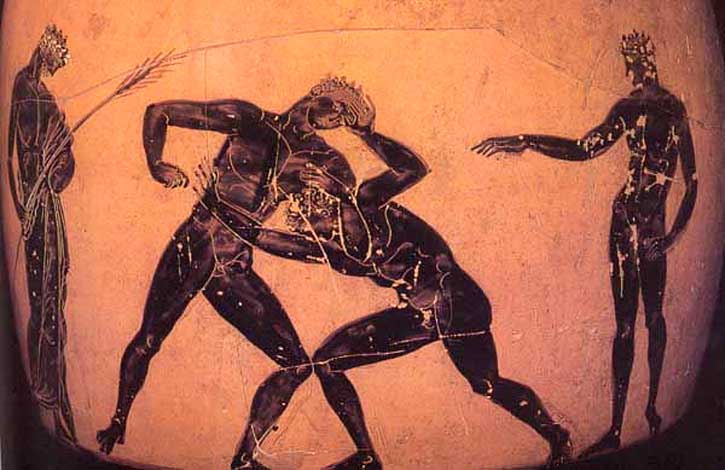

So -- let's look at what Jaeger has said in relationship to this vase painting:

What's happened here is that in a previous duel, Hektor has killed Achilles' Lover, Patroklos.

Achilles is then told by his mother, Thetis, who's a Goddess, that if he avenges Patroklos by killing Hektor, his own life will be very short -- that he himself will be killed.

But that if he forgoes the demands of kalon and timé and goes home -- he'll live to a ripe old age.

Achilles then chooses -- and it is a choice -- 'to take possession of the beautiful' -- to take possession of "kalon" -- moral beauty -- by engaging in a one-on-one armed duel with Hektor -- and

killing him.

Jaeger:

Achilles "subordinates his physical self to the demands of a higher aim, the beautiful."

Achilles decides that his physical life is less important than the demands of kalon -- of moral beauty.

"And so the man who gives up his life to win the beautiful, will find that his natural instinct for self-assertion finds its highest expression in self-sacrifice."

So -- and again, this is important -- "the man who gives up his life to win the beautiful, will find that his natural instinct for self-assertion finds its highest expression in self-sacrifice."

The Man who gives up his life to attain Moral Beauty -- finds that his "natural instinct for self-assertion" --

And what is that "natural instinct for self-assertion"?

It is, very simply, the MAN'S AGGRESSION -- his Manly Aggression, his Manly "self-assertion" -- which Jaeger characterizes as a "natural instinct" -- which it is --

Male Aggression is a Natural Instinct -- it's both biological and spiritual --

And so, to continue with Jaeger:

The Man who gives up his life to attain Moral Beauty -- finds that his "natural instinct for self-assertion," his Manly Aggression --

"finds its highest expression in self-sacrifice."

"self-sacrifice"

Self-sacrifice is the highest expression of Manly Aggression.

And what is self-sacrifice?

It's selflessness -- which as I said, just a few lines above, is NOBLE.

And every Warrior Band, every Warrior, understands that -- which is why we, in the US, and even today, have a Medal of Honor.

And note the word "honor," which connotes Moral Beauty, which connotes Self-Sacrifice.

So -- kalos means both beautiful and noble ; and kalon, the noun formed from that adjective, means Moral Beauty -- which itself is Noble.

And that Moral Beauty and that Nobility is most truly expressed in Hand-to-Hand Fight -- either without weapons, as in Greek Fight Sport --

or on the battlefield:

And, of course, this Fighting is a function of Manhood.

Which *means,* and indisputably, that for the Greeks, Moral Beauty is a function of Manhood ;

And that functionally and reductionally, Moral Beauty is Manhood.

Fighting Manhood.

And Fighting Manhood is Moral Beauty.

"Fighting Manhood is Moral Beauty ; Moral Beauty is Fighting Manhood."

That statement has many implications.

For example, it has implications for our interpretation of Plato's Symposion, without question the greatest book about Male-Male Love ever written.

In the Symposion, Eros -- the vast spiritual force which powers that Love -- also powers the spiritual effort which results in a glimpse of pure and absolute Beauty.

Beauty which is immutable and eternal.

That Beauty is clearly Moral Beauty -- Goodness.

But if Moral Beauty is actually Fighting Manhood, then what's being seen -- as a result of that immense *erotically-powered* spiritual effort -- is Pure and Supreme Manhood.

Pure and Supreme Fighting Manhood.

Here's how, in the Symposion, Sokrates describes this Supreme Manly Moral Beauty -- this Absolute

Manhood -- using the word Kalon -- which is Manly Moral Beauty which is, ultimately and reductionally, Fighting Manhood -- and

contrasting it with the word aischros -- that which is ugly, deformed, shameful,

disgraceful, base, and infamous:

All other things are Manly through a participation of it, with this

condition, that although they are subject to production and decay, it

never becomes more, or less, or endures any change.

When any one, ascending from a correct system of Manly Love, of Manly

Eros, begins to contemplate this Supreme and Absolute Manhood, he

already touches the consummation of this labour.

. . .

A Life spent in the contemplation of this Supreme Manhood, is the Life

for Men to Live.

Which if you chance ever to experience, you will esteem far beyond

gold and rich garments, and even beyond those handsome persons whom

you and so many others now gaze on with astonishment, and are prepared

neither to eat or drink, so that you may behold and live for ever with

these objects of your love.

What then shall we imagine to be the aspect of the Supreme Manhood

itself, simple, pure, uncontaminated with the intermixture of human

flesh and colors, and all other idle and unreal shapes attendant on

mortality, the divine, the original, the supreme, the self-consistent,

the monoeidic Manhood itself? What must be the life of him who dwells

with and gazes on that which it becomes us all to seek?

To him alone belongs the prerogative of bringing forth not images and

shadows of virtue, for he is in contact not with a shadow, but with

Reality; with Virtue -- that is, Manhood -- itself, in the production

and nourishment of which he becomes dear to the Gods, and if such a

privilege is conceded to any human being, himself immortal.

So:

This essentially inner knowledge of Supreme and Absolute Manhood, Manliness, Manly Spirit --

this inner knowledge of Absolute Manhood, which is the prerogative of the Man, the Fighting Man, the Warrior, who Loves another Man -- purely and incorruptibly --

this inward knowledge of Absolute Manhood is what enables that Man to become involved in the production and nourishment of Manliness -- in the "outer" world -- the daily, physical, world of the senses.

That's in the Symposion -- a work by an Athenian author and thinker.

And, interestingly, in the Symposion, Plato, in speaking of the Man whose inner knowledge of Absolute Manhood has led him to become involved in the production and nourishment of Manliness -- in the "outer" world -- the daily, physical, world of the senses -- cites in particular, Lycurgus, the Spartan Law-Giver:

~Plat. Sym. 209d, translated by Shelley.

And the word Shelley has translated as "guardian" also means, and more commonly, saviour --

And of course Plato is pointing to the role the Spartans -- and their Ideal of Fighting Manhood -- played in both guarding and then saving Greece from the Persians.

And he's right to do so.

For it was the Spartans who took the idea, understood by every Greek -- that "Fighting Manhood is Moral Beauty and Moral Beauty is Fighting Manhood" -- and truly ran with it.

The Spartans formulated a code which they called "ta kala."

"Ta kala" is simply the plural of "to kalon," and so it literally means, "the Moral Beauties."

But it's never translated that way.

Usually it's translated as something like "the code of honour."

But classicist JE Lendon, brilliantly, I must say, and recognizing, I assume, that that translation is now inadequate, translates it as "The Noble Way."

That's, I repeat, brilliant, and more than adequate for his purposes -- but not for ours.

So I translate it as "The Noble Warrior Way of Manly Moral Beauty."

Because I think that's 1.) necessary for you guys; and 2.) closer to the way the Spartans would have thought of it.

Not, of course, that the Spartans, notoriously "laconic," would have needed or wanted all that verbiage.

To them, it would have simply been --

And guys, you need, if you click on that link, to look under Arabic numeral 3, Roman numerals II and IV.

Now:

The passage Prof Lendon is referring to is in Xenophon -- and I'll get to it in a moment.

But if we look at the great Greek poet Pindar, who lived about a hundred years before Xenophon and who wrote poems praising athletic victors in the various games, Olympic, Pythian, Isthmian, and Nemean, we see that Pindar routinely uses Ta Kala to refer to both "noble deeds" and "actions which are morally beautiful."

For example, in a victory ode to Hagesidamos, winner in boys' boxing at the Olympics in 476 BC, Pindar speaks of "a man who has performed Ta Kala" -- which, in classicist Wm Race's translation, becomes "noble deeds."

But then in a separate victory ode, also to Hagesidamos, Pindar writes of "a man who is experienced in Ta Kala" -- which Prof Race then translates as "beautiful things."

Which is clearly meant to mean "morally beautiful things" -- morally beautiful acts which exist in a highly competitively athletic and military culture -- a Warrior culture.

And Prof Race is correct to have in his translations of Ta Kala the ideas of both noble and beautiful -- morally beautiful.

Again, in a highly competitive Warrior context.

Hagesidamos is, after all, a victor in boxing -- and boys' boxing to boot.

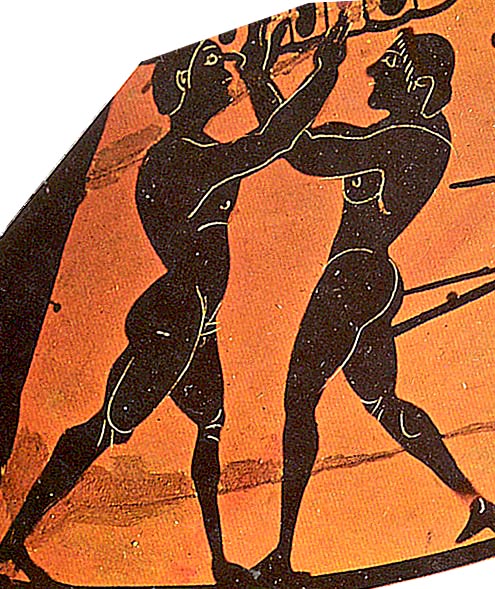

In another ode, addressed to Kleandros, a youthful victor in pankration, -- and the name Kleandros, by the way, means something on the order of "Glorious Man" -- Pindar says that Kleandros is not without experience of Ta Kala -- noble deeds, morally beautiful noble deeds.

We discuss that ode, and Kleandros, in Agoge IV: Excellence, Honor, and the Molding of Men:

~ Isthmian 8, translated by Wm Race

Ta Kala -- noble deeds -- which are also morally beautiful.

So we can see that kalos -- meaning noble and beautiful -- has now become Ta Kala -- noble deeds which are, by definition, morally beautiful.

Jaeger: "For the Greeks, beauty meant nobility also."

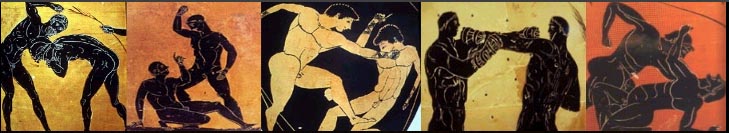

And that these morally beautiful noble deeds can be said to be characteristic of young men who are victorious in Fight Sport -- including Boxing and Pankration.

Which takes us to Xenophon -- writing about a hundred years after Pindar.

Xenophon was an exiled Athenian who fought in battle side by side with the Spartans, was a buddy of the Spartan king Agesilaus, lived on an estate gifted him by the Spartans, sent his sons to be raised in the Spartan agogé -- and who apparently spent a lot of time simply hanging out at Sparta.

All of which is to say that when Xenophon speaks of Ta Kala -- the Spartan Code -- The Spartan Noble Way -- The Spartan Noble Warrior Way -- The Spartan Noble Warrior Way of Manly Moral Beauty --

we should pay attention.

Xenophon first uses Ta Kala in talking about the Strife of Valour --

and it's this use of Ta Kala which Prof Lendon *specifically* references in a footnote giving the source of his statement that

So -- the source for Ta Kala -- Prof Lendon's "The Noble Way" -- is this passage in Xenophon's Lakedaimonian Constitution:

He believed, therefore, that if he could match the young men together in a Strife of Valour [areté -- a Strife, a Combat, therefore, of Manhood], they too would reach a high level of manly excellence [andragathia]. I will proceed to explain, therefore, how he instituted matches between the young men.

The Ephors, then, pick out three of the very best among them. These three are called Commanders of the Guard. Each of them enrols a hundred others, stating his reasons for preferring one and rejecting another.

The result is that those who fail to win [attain to, hit the mark of] the honour [Ta Kala] are at war both with those who sent them away and with their successful rivals; and they are on the watch for any lapse from the code of honour [Ta Kala -- the noble way, the noble warrior way, the noble warrior way of manly moral beauty -- and the beautiful path of noble moral achievements].

Xen. Const. Lac. 4.4, translated by Marchant

So -- Marchant, writing in 1925, translates "Ta Kala" as "honour" and "code of honour."

And while that may have been okay in the 1920s, it no longer suffices; and Prof Lendon is exactly right to speak instead of

And we can, I feel, add to Prof Lendon's words the words I've added -- that is, Warrior, and Manly Moral Beauty, because, as I said, they'd have been understood to be there by the Greeks -- but aren't by folks like ourselves --

and what we get when we add those words is -- The Noble Warrior Way of Manly Moral Beauty.

That's the Spartan Code.

And we can plug that into Marchant's translation:

Lycurgus believed, therefore, that if he could match the young men together in a Strife of Valour, a Combative Contest about, of, and for Manhood, they too would reach a high level of Manly Goodness [andragathia]. I will proceed to explain, therefore, how he instituted matches between the young men.

The Ephors, then, pick out three of the very best -- and the word Xenophon uses for "best" suggests young Men in the full bloom, prime, and perfection of their youthful Manhood -- among them. These three are called Commanders of the Guard. Each of them enrols a hundred others, stating his reasons for preferring one and rejecting another.

The result is that those who fail to measure up to Ta Kala -- The Noble Warrior Way of Manly Moral Beauty -- are at war both with those who sent them away and with their successful rivals; and they are on the watch for any lapse from Ta Kala -- The Noble Warrior Way of Manly Moral Beauty -- The Beautiful Path of Noble Moral Achievements.

So there's the Spartan Code -- Ta Kala -- The Noble Warrior Way.

The Ephors -- high government officials and overseers -- pick out three of the very best young men -- best in the sense, clearly, both of being in the prime and perfection of their young Manhood, and, therefore, of exemplifying Ta Kala.

These three each enrols a hundred others -- giving three hundred total.

Those young men who are rejected -- who don't make the cut -- are then "at war both with those who sent them away and with their successful rivals; and they are on the watch for any lapse from Ta Kala -- The Noble Warrior Way of Manly Moral Beauty -- The Beautiful Path of Noble Moral Achievements."

That's only natural, and it's what Lycurgus wants -- he wants to create a rivalry, a competition, between those chosen and those not, the focus of which is the Spartan code -- the Noble Warrior Way.

The result is a Strife of Valour.

That is, a Strife, a Struggle, a Combat of, about, and for -- Manhood.

For, as Xenophon goes on to say

Here then you find that kind of strife that is dearest to the Gods, and in the highest sense political -- the strife that sets the standard of a brave man's conduct; and in which either party exerts itself to the end that it may never fall below its best, and that, when the time comes, every member of it may support the state with all his might.

And they are bound, too, to keep themselves fit, for one effect of the strife is that they fight whenever they meet; but anyone present has a right to part the combatants.

If anyone refuses to obey the mediator the Warden [the paidonomos, the official who heads up the agogé] takes him to the Ephors; and they fine him heavily, in order to make him realize that he must never yield to a sudden impulse to disobey the laws.

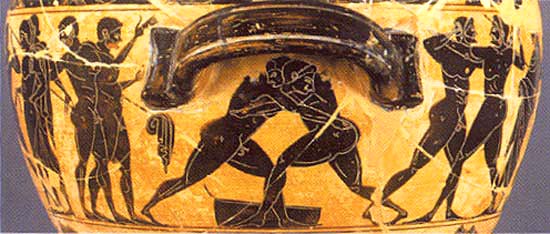

"they fight whenever they meet"

What that tells you is that to the Spartans -- and to the other Greeks, as we saw in Pindar -- part of the noble way, part of the way of manly moral beauty and noble moral achievements -- involves Fighting.

Not just metaphorical strife -- but actual physical Fighting.

And, by the way, the word used for "fight" connotes FIST-Fighting -- Boxing:

Now -- I've spoken before about the Incantational aspect of the way ancient writers like Plato use words relating to Men, Manhood, Manliness, and Virility.

For example, in Death of an AIDS Activist, I talked about

Manhood as delineated in Plato's Symposion.

In Plato's Symposion or Banquet or Drinking Party, a number of Men

describe the God Eros -- the God of Romantic Passion.

Male Romantic Passion.

Manly Romantic Passion.

Because that's who and what Eros is -- along with his twin and sometime rival, Anteros -- Counter-Love, Requited-Love.

Agonistic Love.

Manly Love.

Again, Love is an Agon.

And the Men speaking -- all -- to a Man -- describe the Men caught up in

that Agonistic Love, that Romantic Passion -- as Manly -- indeed, as Most Manly.

There are a number of words for Manly.

One is arren.

Arren -- as in Ares -- the God of Manhood.

Another is andreios.

Andreios -- as in Andros -- the Men of Manhood.

So -- in Symposion, one speaker says -- and this is somewhat lost in

translation -- that Men who are Arren -- seek out Arren -- they pursue

it; and that such Men are the most Manly (andreiotatos)-- that they're

Manly and Virile -- andreias kai arrenopias.

Again, it's hard to translate, but --

Andros = Man

Andreios = Manly

Arren = Male, Masculine, Manly, Strong.

Men who are into Men are Manly and seek out Manliness in other Men ;

such Men are the most Manly -- they're Manly and Virile.

So basically, when the Greeks talk about Eros -- Manly Love,

Manly Romantic Passion --

they keep repeating these words which mean Male and Masculine and

Manly and Virile --

and the repetition becomes in effect an Incantation.

An Incantation:

An Incantation of Manliness.

An Incantation of the Male.

An Incantation of Manhood.

These guys are high on Manhood.

And I do mean "high."

Because, ultimately, says Sokrates, Eros leads to what we would call a

"higher state of consciousness."

To a Vision.

A Vision of Absolute Beauty.

Absolute Moral Beauty.

Which is Absolute Manliness.

Absolute Manhood.

Now -- we can see that Xenophon -- who's a very different sort of person and thinker than Plato -- nevertheless does the same thing.

He produces, in his description of the, per Marchant, "Strife of Valour," an Incantation of Men, Manhood, Manliness, Goodness, Combat, Strife and the Morally-Beautiful-Because-Manly -- Fight:

Lycurgus believed, therefore, that if he could match the young Men together in a Strife of Valour, a Combative Contest of Manhood, they too would reach a high level of Manly Goodness and Virtue [andragathia]. I will proceed to explain, therefore, how he instituted matches between the young Men.

[And the word Marchant translates as "instituted matches" = symballo = συμβαλλω = "to bring men together in hostile sense, to set them together, match them, etc. . . . to join in fight."

so "instituted matches" actually reads -- "how he brought the young Men together in Fight, how he joined the young Men, matched the young Men -- in Fight."]

The Ephors, then, pick out three of the very best among them. These three are called Commanders of the Guard. Each of them enrols a hundred others, stating his reasons for preferring one and rejecting another.

The result is that those who fail to measure up to Ta Kala -- The Noble Warrior Way of Manly Moral Beauty -- are at war [polemeo πολεμεω = do battle, fight, be at war] both with those who sent them away and with their successful rivals; and they are on the watch for any lapse from Ta Kala -- The Noble Warrior Way of Manly Moral Beauty -- The Beautiful Path of Noble Moral Achievements.

Here then you find that kind of strife that is dearest to the Gods, and in the highest sense political -- the strife that sets the standard of a Brave Man's [agathon] conduct; and in which either party exerts itself to the end that it may never fall below its best, and that, when the time comes, every member of it may support the state with all his might.

And they are bound, too, to keep themselves fit, for one effect of the Strife is that they Fight [machomai μαχομαι] whenever they meet; but anyone present has a right to part the combatants.

If anyone refuses to obey the mediator, the Warden [the paidonomos, the official who heads up the agogé] takes him to the Ephors; and they fine him heavily, in order to make him realize that he must never yield to a sudden impulse to disobey the laws.

So -- what we have is

Xenophon is a less artful writer than Plato -- few can match Plato's stylistic genius -- but what comes through in Xenophon's account of the "Strife of Valour" is his intense passion for this intersection of Manhood and Goodness and Manly Virtue and Fighting:

And just as with Plato, we can see the words Men, Manhood, Manly, Goodness, Virtue, Strife, Combat, Fight -- and Moral Beauty -- joined together and repeated over and over again.

And the effect too, as with Plato, is Incantational.

Plato's Incantation is about Manly, Goodly, Men -- Loving each other.

Xenophon's Incantation is about Manly, Goodly, Men -- Fighting each other.

And what powers both Incantations -- is Manhood.

Now -- clearly, in Xenophon, the Manhood is Fighting Manhood.

That's easy, hopefully, for you guys to see.

What about in Plato?

Oh yes, in Plato, the Manhood is Fighting Manhood too.

Which I will now demonstrate.

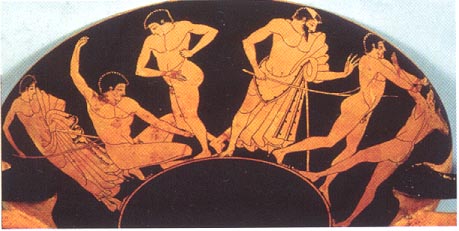

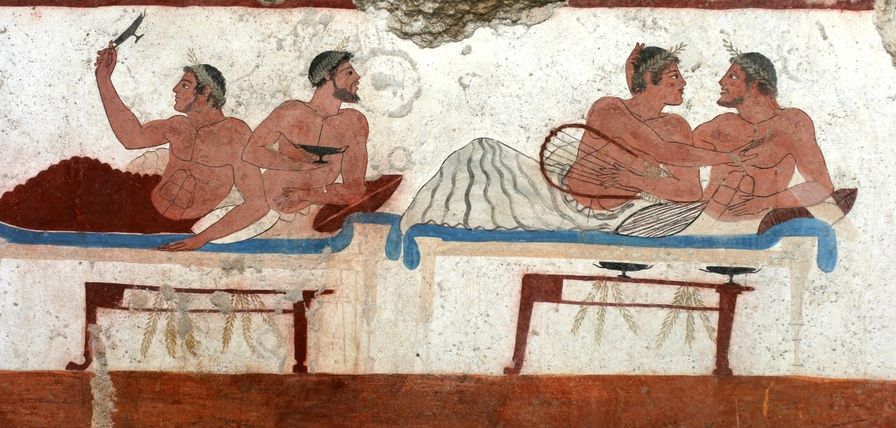

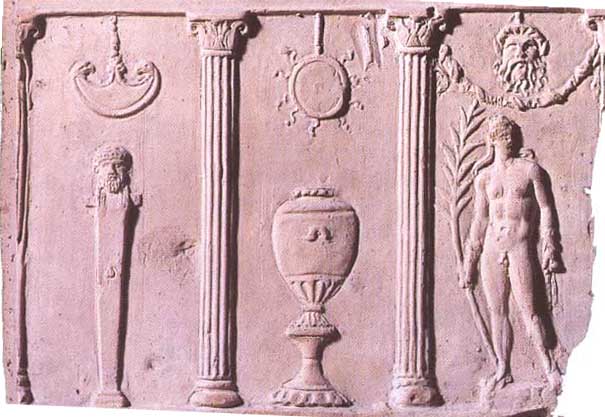

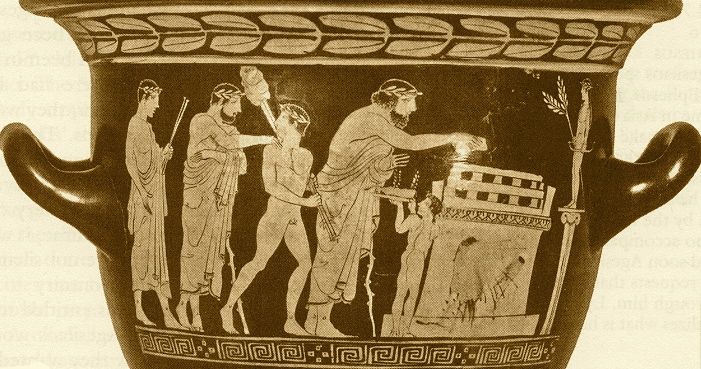

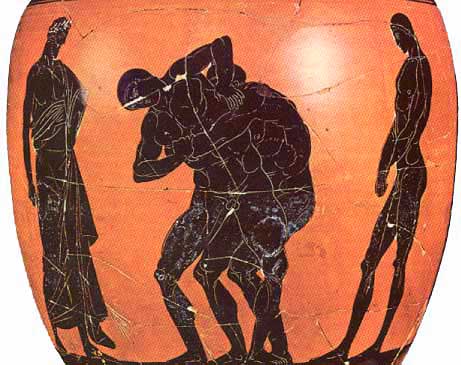

First of all, you see the guys at the Symposion:

And you can see that three of the guys are holding drinking cups, cups which have handles and a little pedestal.

Such a cup was called a kylix, and was used for drinking wine -- at Symposia.

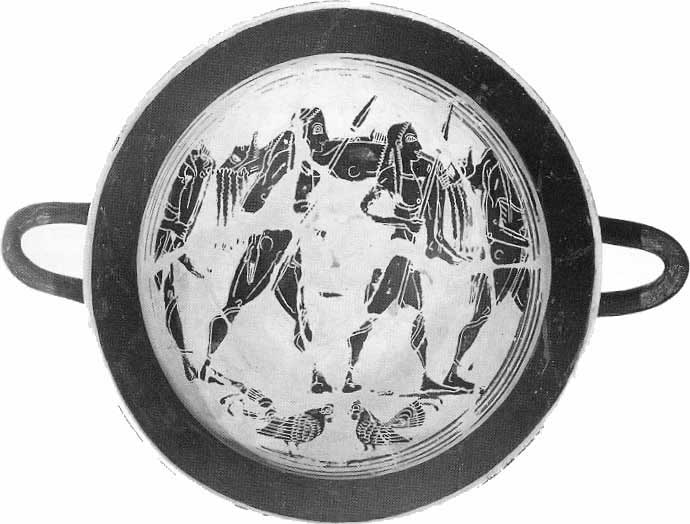

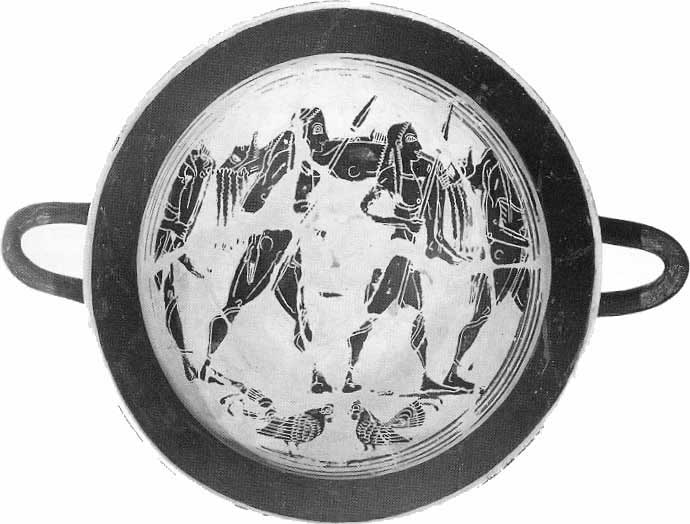

The interior of the kylix was often decorated, and this painting, which I've made iconic in our reductional and incantational Lexicon of Manhood --

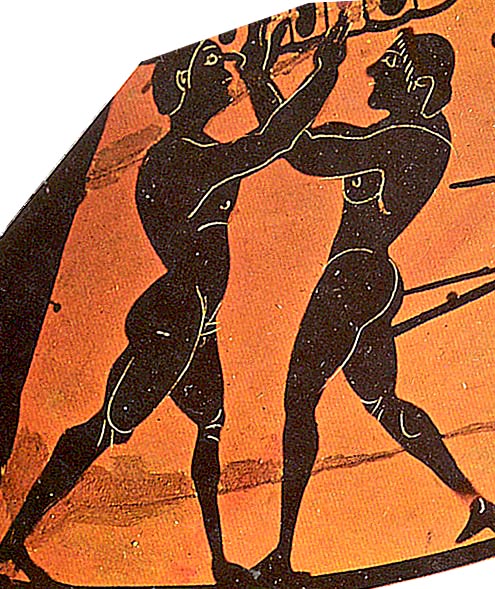

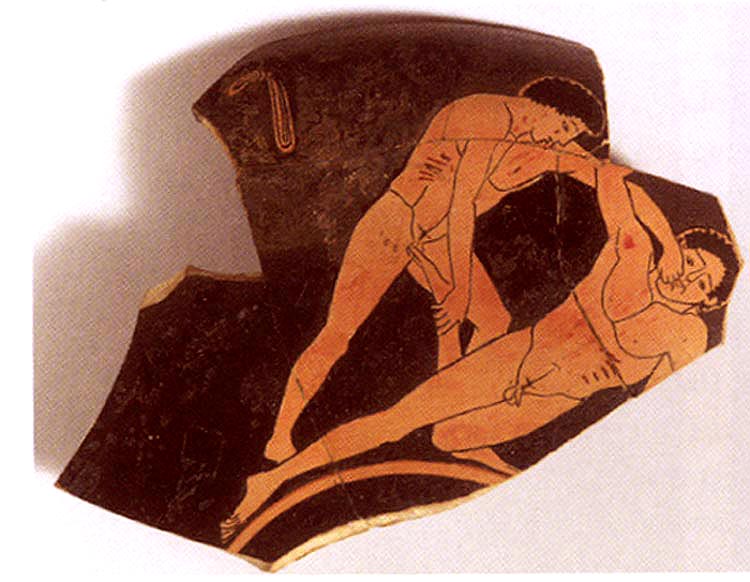

is from the interior of a kylix.

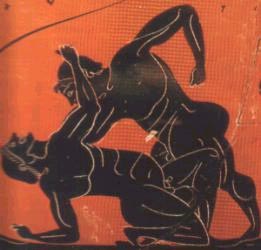

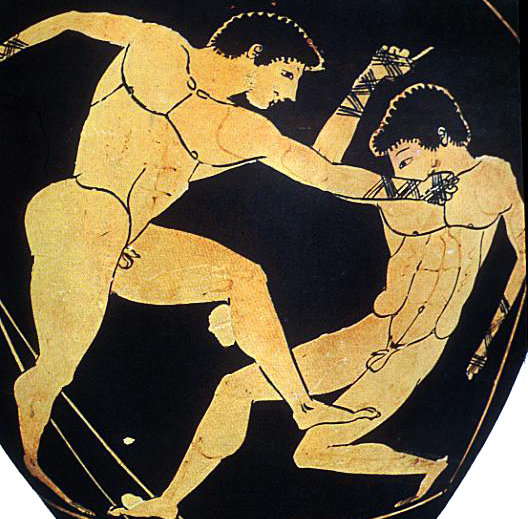

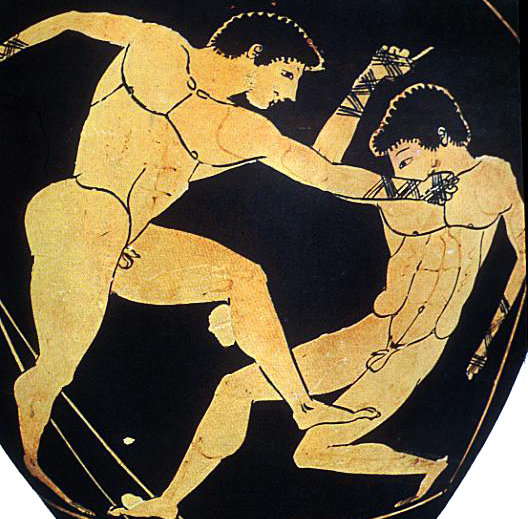

So -- guys would have drunk from such a cup, and when the wine, which is dark, was all imbibed, this is what they would have seen:

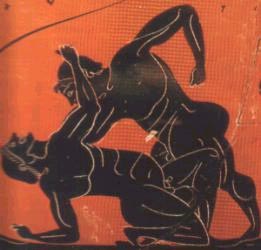

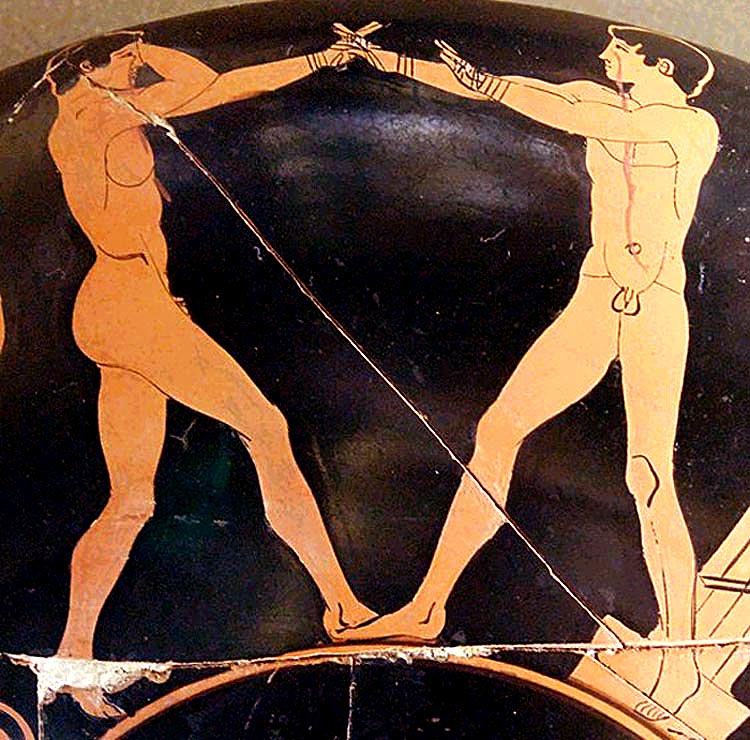

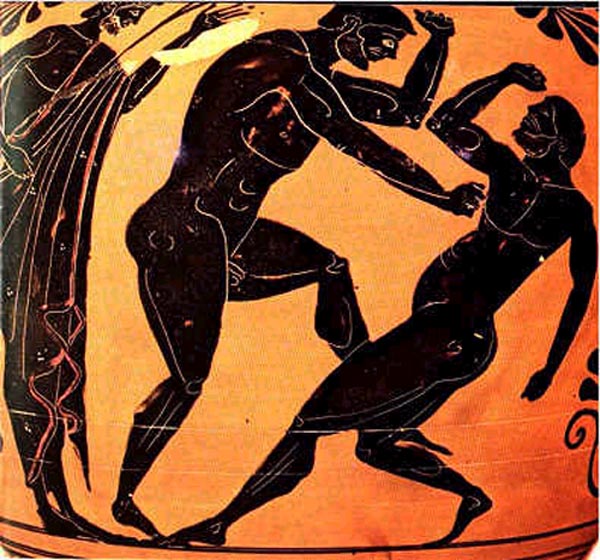

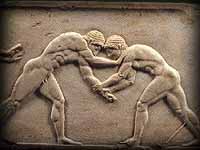

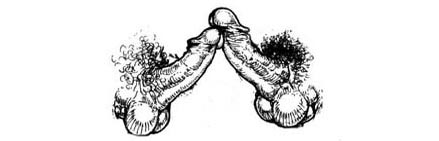

Two nude youths boxing -- or perhaps fighting in pankration:

That's Fighting Manhood.

And that's the sort of Manhood which guys at a Symposion -- all of whom were Warriors -- wanted to see.

And if you still don't understand that, you need to read the discussion of Xenophon's Symposion in Prudence or the Pill.

Here's a bit of that discussion, which turns on the love of Callias, a pro-Spartan Athenian aristocrat, for the youth Autolycus, who has just won a victory in Pankration:

From Xenophon's Symposium:

Socrates now opened up another new topic for discussion. "Gentlemen," said he, "it is to be expected of us, is it not, when in the presence of a mighty deity that is coeval with the eternal Gods, yet youngest of them all in appearance, in magnitude encompassing the universe, but enthroned in the heart of man -- I mean Eros -- that we should not be unmindful of him, particularly in view of the fact that we are all of his following?

For I cannot name a time when I was not in love with some one, and I know that Charmides here has gained many lovers and has in some instances felt the passion himself; and Critobulus, though even yet the object of love, is already beginning to feel this passion for others.

So -- Sokrates and the other Men are in the presence of the mighty God Eros because Callias is in love with Autolycus.

Indeed, all the Men at the symposion, says Sokrates, are followers of Eros.

Meaning that they ALL have, throughout their lives, LOVED other MEN.

Sokrates:

That's a very clear statement -- isn't it -- of the ubiquity of Male Passion for other Males.

As my foreign friend says:

It is, rather, a Universal Phenomenon, especially strong among MASCULINE Men.

Male desire for other Men cannot be tied to a minority group -- like "gays."

It is rather a Ubiquitous and Universal Phenomenon, especially strong among MASCULINE Men.

A point which Sokrates proceeds to emphasize:

But as for you, Callias, all the city knows that you are in love with Autolycus, and so, I think, do a great many men from abroad. The reason for this is the fact that you are both sons of distinguished fathers and are yourselves in the public eye.

Now, I have always felt an admiration for your character, but at the present time I feel a much keener one, for I see that you are in love with a person who is not marked by dainty elegance nor wanton effeminacy, but shows to the world physical strength and stamina, virile courage and sobriety. Setting one's heart on such traits gives an insight into the lover's character.

So -- we can see that the love object, though still a youth, has Manly qualities -- he fights in the Pankration, and "shows to the world physical strength and stamina, virile courage and sobriety."

And of course, "virile courage" is Andreia --

MANHOOD.

FIGHTING MANHOOD.

Physical strength and stamina, virile courage -- Andreia -- and sobriety -- Sophrosyne --

these are all attributes of Manliness and of what we call Brave Beauty, and, says Sokrates,

So -- the love object, the beloved, is a Victor in Pankration.

He's a FIGHTER.

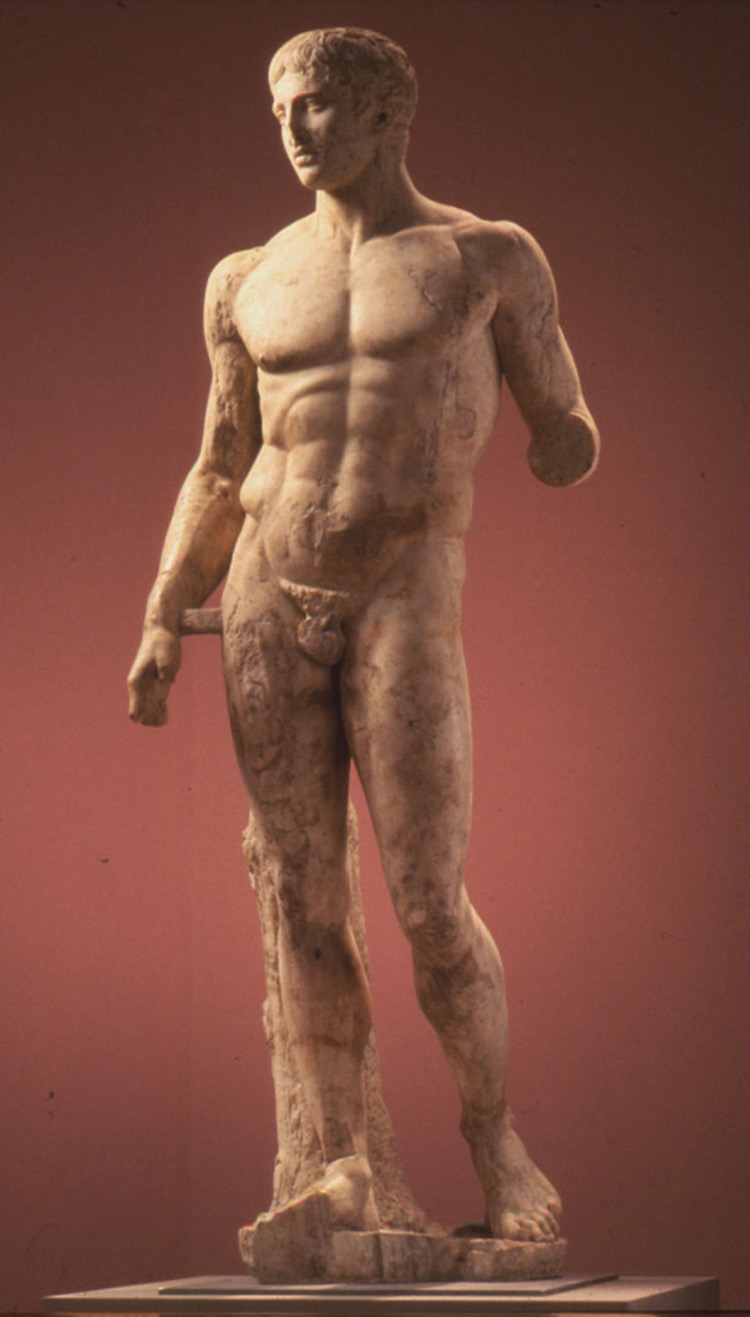

MANLY and MASCULINE:

And his Manly Aggression is the source of his Brave Beauty.

Like Warrior NW has said:

aggression and the beauty of guys

His beauty, then, is both physical and moral.

He's possessed of physical strength, stamina, and "virile courage" -- which is -- FIGHTING MANHOOD.

So : what you see at the Symposia / All-Male Messes -- as well as at the Palaistrai / Gymnasia -- because all four are loci of male-male courtship and romance --

What you see is the intersection of Eros and Ares -- or, if you prefer, Eros and Agon.

The two -- Love and Aggression -- are united in Greek thought.

That is to say, that Fighting Manhood -- and Romantic Passion between Men -- are inextricably intertwined and inseparably united.

They cannot be divided or parted.

Now, and returning to Ta Kala and Xenophon's Struggle for and about Manhood:

What about the bit about obedience -- the young Fighters, says Xenophon, "must never yield to a sudden impulse to disobey the laws."

I'm going to get to that -- and you'll see that it connects Ta Kala very directly to Manly Love and to dying in battle for and with your Lover.

But first:

Xenophon also uses Ta Kala in another passage, this one in the Hellenika, when a Spartan admiral named Teleutias, whom Xenophon greatly admired -- he describes him, at one point, as "a true man," and for Xenophon there's no greater praise -- Teleutias is addressing his troops:

~Xen. Hell. 5.1.16, translated by Brownson

So -- Brownson, also translating in the 1920's, says "glory" -- but, and wow, as we've just seen -- it means a lot more than that.

Marincola, translating in 2009, says that Sparta won her "fairness and goodness" -- and certainly "goodness" gets closer to the sense of Ta Kala -- but again, Ta Kala means more than just goodness.

It means Sparta's noble moral beauty and her noble achievements.

Which to the Greeks -- are glorious.

So this is how the Men -- the Spartan Warriors -- Teleutias is addressing would have heard that passage:

I know -- "morally beautiful noble achievements" sounds awkward.

But the point is that the Spartans had that idea compressed into two words: Ta Kala.

Ta Kala then becomes a shorthand for a manly way which is morally beautiful -- and morally noble.

And Xenophon also uses Ta Kala in another passage, where he's describing the men making up a Spartan expeditionary force being sent out to punish a city-state which has gotten out of line; Xenophon says the force was made up of Spartan Warriors, and of non-Spartan Warriors who were allied to the Spartans -- and among them were the illegitimate sons of Spartiatai -- illegitimate sons who'd been brought up as Spartans:

There followed with him also many of the Perioeci [resident non-citizens] as volunteers, men of the better class, and aliens who belonged to the so-called foster-children of Sparta [non-Spartan youths who, like Xenophon's own sons, had been raised in the agogé], and sons of the Spartiatai [full-blooded Spartans] by Helot women, exceedingly finelooking men, not without experience of the good gifts [Ta Kala = the noble ways of manly moral beauty] of the state.

~Xenophon Hellenika V.3.9, translated by Brownson

One classicist says of this passage:

If that's correct -- and only Xenophon -- and the Spartans who were there -- knows exactly what Xenophon meant by Ta Kala in that context -- then the Spartans saw the agogé as part of Ta Kala -- The Beautiful Path of Noble Moral Achievements.

Or, perhaps, the Beautiful Path to Noble Moral Achievements.

There followed with him also many of the Perioeci [resident non-citizens] as volunteers, men of the better class, and aliens who belonged to the so-called foster-children of Sparta [non-Spartan youths who, like Xenophon's own sons, had been raised in the agogé], and sons of the Spartiatai [full-blooded Spartans] by Helot women, exceedingly finelooking men, not without experience of the city's Beautiful Path to Noble Moral Achievements, its Noble Warrior Way of Manly Moral Beauty.

In which case ALL of Spartan life was intended -- as Plutarch says it was -- to achieve that goal.

And remember that we can variously translate the word.

As The Noble Warrior Way of Manly Moral Beauty.

or The Beautiful Warrior Path of Noble Moral Achievements.

But notice that the word "beautiful" is part of it.

Because that's the Greek conception of Noble.

As we discussed earlier, and as classicist Werner Jaeger explains, Aristotle says it's

The last phrase is so entirely Greek that it is hard to translate. For the Greeks, beauty meant nobility also. To lay claim to the beautiful, to take possession of it, means to overlook no opportunity of winning the prize of the highest areté.

And what is the highest areté?

Moral Heroism.

Now --

Let's talk about obedience.

At Thermopylai, where Leonidas and his 300 Spartans died defending the freedom of Greece, there was, carved in stone, an epitaph:

Go tell the Spartans, stranger passing by,

So the dead men are saying -- indeed boasting -- that they died *in obedience* to Spartan law:

So -- at Sparta, uniquely among the Greek city-states, the ability to obey -- as well as to command -- was seen as central.

And Spartans competed in obedience.

Such competition to obey -- was part of Ta Kala.

And obedience included -- No Retreat, No Surrender -- Fighting to the Death.

Thermopylai was the most famous instance of that.

But hardly the only one.

There were many.

And among them was the death of the Spartan commander Anaxibios -- and "the young man who was his lover" -- as reported by, once again, Xenophon in his Hellenika:

Anaxibios then took his shield from his shield-bearer and died fighting at his station. The young man who was his lover remained by his side, and about twelve of the Spartan governors . . . also died fighting along with him.

~Xen. Hell. 4.8.38, translated by Brownson and Marincola

So -- Anaxibios saw what he was doing as part of Ta Kala -- as part of the Noble Warrior Way.

As did "the young man who was his lover," and the twelve Spartan governors.

Which is not surprising -- they'd been raised to think that way.

They've been raised to both command -- and obey.

Even when -- especially when -- obedience meant dying at your post.

What happened to the other men -- to whom Anaxibios had given permission to run away?

Nothing good, according to Xenophon:

Xenophon believes in Sparta and in Ta Kala.

And here he's clearly presenting Anaxibios and the young man who was his lover, along with the twelve Spartan governors -- that is, the guys who stood their ground and died -- as morally superior to the guys who ran -- and died anyway.

For, as Anaxibios says, "Men, it is a fine thing, a kalon, a noble deed and a morally beautiful achievement -- for me to die here."

And obviously the young man who was his lover -- agreed.

Indeed, it's virtually unthinkable, in an ancient context, for the lover not to have stayed with him.

Maybe that happened -- but you NEVER hear about it.

NEVER.

All you hear about, over and over and over again -- is Fidelity.

Unto Death.

JE Lendon:

Werner Jaeger:

Now -- were Pindar and Xenophon the only Greeks to use to kalon [moral beauty] and ta kala [the noble warrior way of manly moral beauty] in this way?

No -- of course not.

It was part of common Greek discourse.

So, for example, in Book V of the Republic, Plato is discussing how the "Guardians" -- the Warrior Caste of his ideal city-state -- and ideal Man -- will possess nothing, not even wives or children -- and that this will keep them free of dissensions and disuptes:

"They will necessarily be quit of these," he said.

"And again, there could not rightly arise among them any law-suit for

assault or bodily injury. For as between age-fellows [men of the same

age, comrades] we shall say that self-defence [to defend oneself, to

repel an assault] is honorable [kalon] and just [dikaios], thereby

compelling them to keep their bodies in condition."

"Right," he said.

"And there will be the further advantage in such a law that an

angry man, satisfying his anger in such wise, would be less likely to

carry the quarrel to further extremes."

"Assuredly."

"As for an older man, he will always have the charge of ruling and

chastising the younger."

~Plat. Rep. 5.464e, translated by Shorey

Let's play that again.

Plato, the greatest thinker of his age, and many believe, any age, is saying that among the Warriors in his ideal state,

And you'll notice that the distinguished translator, Paul Shorey, has a footnote after the word for age-mate/comrade -- which reads as follows:

So, Shorey refers us back to Xenophon's account of the Strife of Valour in "Rep. Lac. 4.5":

Here then you find that kind of strife that is dearest to the Gods, and in the highest sense political -- the strife that sets the standard of a brave man's conduct; and in which either party exerts itself to the end that it may never fall below its best, and that, when the time comes, every member of it may support the state with all his might.

And they are bound, too, to keep themselves fit, for one effect of the strife is that they fight whenever they meet; but anyone present has a right to part the combatants.

So -- what both Plato and Xenophon are saying -- and it's truly eye-opening for Men like ourselves, living in the times we do --

is that Fist Fights to settle disputes -- are Morally Beautiful -- and Just -- that is, Well-Ordered.

And that such Fights have the benefit, for the Fighters, of "compelling them to keep their bodies in condition" (Plato) -- and making them "bound, too, to keep themselves fit, for one effect of the strife is that they fight whenever they meet" (Xenophon).

So -- and this is not a small point -- the quest for Moral Beauty -- Kalon, Ta Kala -- contributes to at least the first two of the three Goods of the Body -- Health, Strength, and Beauty -- while Nourishing the Soul's never-ending Quest for Absolute Manhood -- both, through FIGHTING.

MEN NEED TO FIGHT.

It strengthens their bodies, it enriches them spiritually.

Oh, and by the way, what sort of Fighting is this -- is it with weapons?

Shorey refers us to Plato's Laws, 880:

If a man of a certain age beat a man of his own age, or one above his

own age who is childless, -- whether it be a case of an old man

beating an old man, or of a young man beating a young man, -- the man

attacked shall defend himself with bare hands, as nature dictates, and

without a weapon.

~Plat. Laws 9.880, translated by R G Bury

So -- what both Plato and Xenophon support, for the settling of disputes -- is Fist-Fighting.

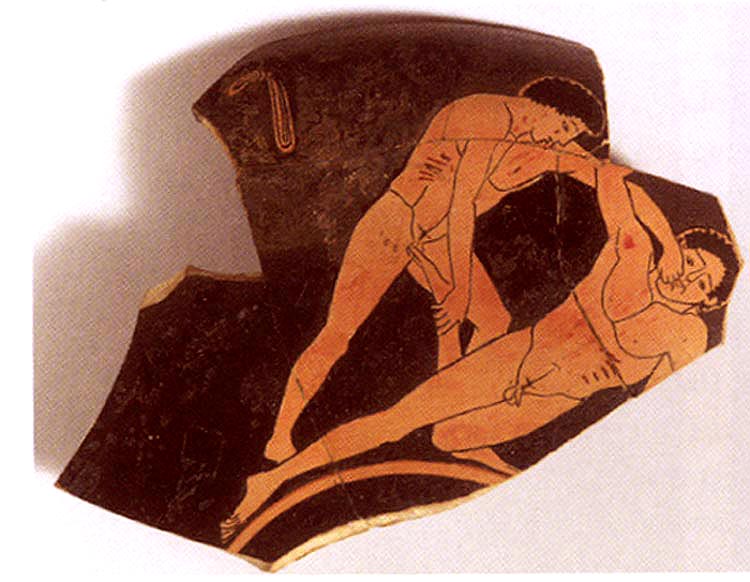

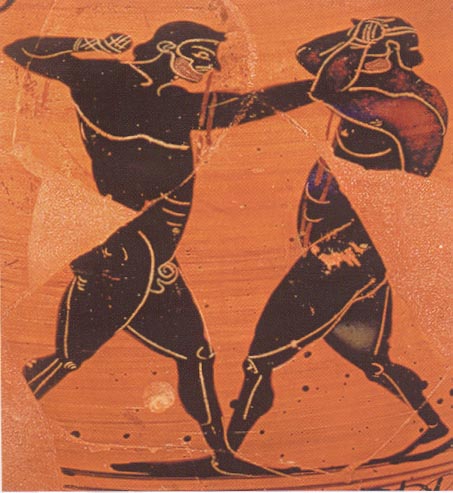

The Brave and Moral Manly Beauty -- of Fist Fighting:

Just two more ancient Greek words to go, guys, and then we'll be ready to move on to the heart of the matter -- in Biblion Deuteron of our Lexicon of Manhood, Primal Love.

This is, to the Greeks at least, very simple:

The term orthos reduces moral righteousness to the flat, angular, straight-up, and standing erect aspects of the Male Body -- of Manhood:

However, because the first definition of orthos given by Liddell and Scott is "straight," and because in our heterosexualized society, the word "straight" is often used to mean "heterosexual," we need to look more closely at orthos.

So:

In English, we've borrowed the ancient Greek word orthos to mean "straight" in a non-heterosexualized context -- think of

orthopedics -- "straight" muscles and bones; and orthodontry -- "straight" teeth.

But, as I've just explained, what orthos actually means in Greek, is "standing erect" --

and thus upright -- as in morally upright, righteous.

For example, Plato uses the word orthos in Bk VII of the Republic, in describing the "Idea of Good."

We're going to define and discuss the Idea of Good in Biblion Deuteron, Book II -- of this Lexicon.

For now, all you need to know is that the Idea of Good is the most powerful force in the Kosmos.

~Plat. Rep. 7.517c, translated by Shorey

So -- you can see first off that Plato links orthos -- standing erect, being morally upright -- with kalos -- noble moral beauty.

Both orthos and kalos are therefore -- Manly.

Which means that if the Idea of Good is "the cause of all that is right [orthos] and

[morally] beautiful [kalos]," the Idea of Good must be -- Manhood.

Now -- some of you may think that's an enormous leap.

I ask you to bear with me, and reserve judgment until we get to Biblion Deuteron, Book II, where I'll explain just why we both can and should make that leap.

For now, let's try simply plugging the word Manhood in -- and seeing how the quote reads:

Remember, and again, that to the ancients, Manhood is by definition Moral.

It's critical that you remember that.

And not confuse our profane reading of "masculinity" -- with the ancients' essentially sacred and virtuous understanding of -- Manhood.

So -- in ancient Greek, orthos means right, means morally right, means righteous, means

standing erect.

It's a typical Manly and Masculinist ancient word identification of Righteousness --

Virtue -- with Manhood -- Phallus.

But -- Phallus not so much in its sexual aspect as in its FIGHTING aspect.

That's why Liddell and Scott say, regarding areté and Ares, that

Manhood.

"the first notion of goodness being that of manhood"

And, Liddell and Scott re-inforce that point by saying that areté is

Manhood.

"goodness, excellence, of any kind, esp. of manly qualities, manhood, valour, prowess"

Manhood.

The first notion of goodness is Manhood -- bravery in war, prowess in

battle, "cf" = compare to Virtus = Latin for Virtue = manliness, manhood, strength, vigor, bravery, courage, excellence = Manhood.

A MAN stands ERECT -- He stands STRAIGHT UP -- to do BATTLE.

Whether that battle is without weapons -- Fight Sport -- with weapons

-- War -- or PhalloMachia -- Phallic Fight.

And Orthos references ALL of those.

What it does NOT reference is the 19th-century word "heterosexual."

Click on the definition of the word ορθος and search for the term "heterosexual."

It's not there.

Because the Greeks didn't make an identification between "straight" --

and fucking pussy.

Recently, someone sent me a picture of a nude male with an erection.

It was labeled "straight-jock-adams."

Neither of those connections -- between "straight" -- that is, "heterosexual" -- and "jock" -- that is, athlete;

nor between "straight" -- that is "morally upright" -- and a male publically displaying his erection -- would have made sense to a Greek.

First of all, ancient Greek athletics took place at the palaistra / gymnasion, which was also where male-male courtships were carried out.

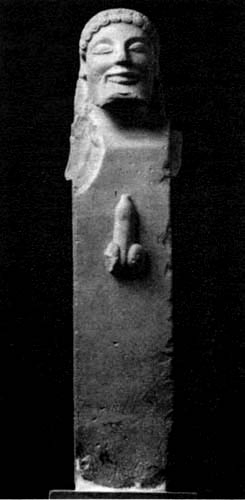

There were statues and bas-reliefs etc -- in those athletic spaces -- of Eros -- the God of male-male Romantic Passion; and Herakles -- God of Strength and Pankration and Lover of Iolaos;

and there were "Herms" -- stylized statues of the God Hermes with an erection.

And there were religious rites carried out within the palaistrai / gymnasia -- in honor of those Gods.

The idea that an athlete would have an exclusive sexual or affectional interest in females -- would have been laughable to the Greeks.

And it certainly wouldn't have been considered "orthos."

It would have been thought odd -- at best.

Nor would a male publically displaying his erection be considered "orthos."

That would have been a severe violation of the most important Greek civic Virtue:

Because, as I discussed in Sexual Freedom -- Sophrosyne was viewed as a function of Manliness -- and a Man was supposed to be Master of his passions -- and not the reverse.

So -- there was nothing orthos about "straight-jock-adams."

And yet many of you guys -- usually the same guys who complain that my posts are too long -- spend HOURS searching the web for images like that one:

of some morally-useless youth with over-built pectorals and an accu-jacked penis.

You need to stop doing that.

Because it makes you morally useless -- and morally worthless -- too.

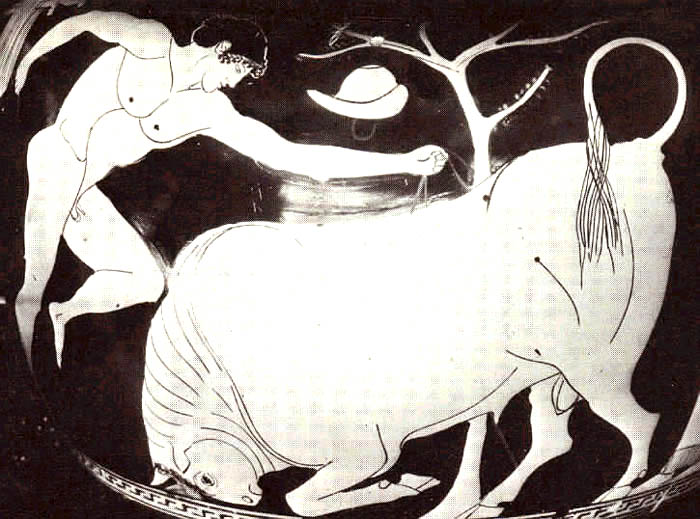

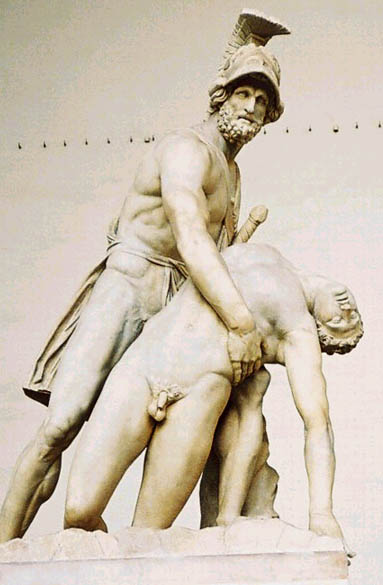

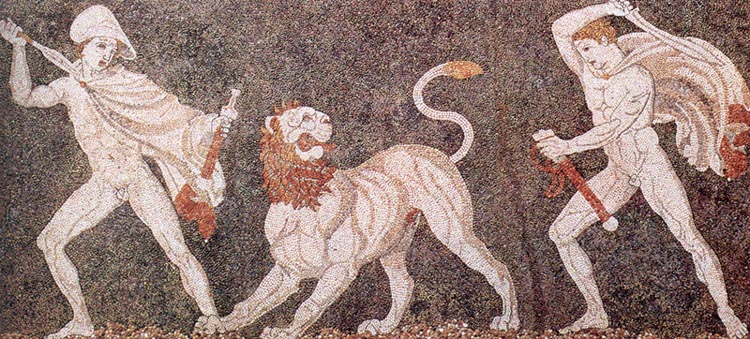

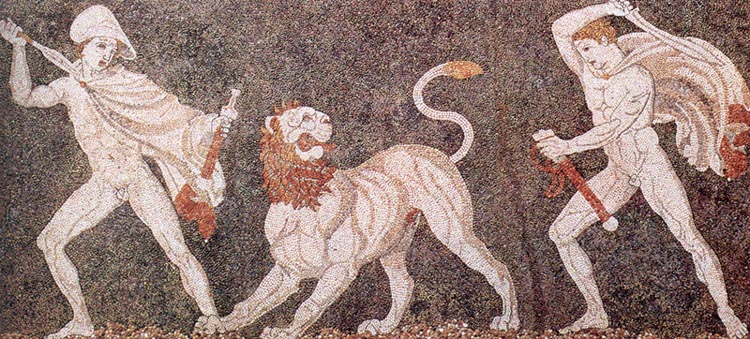

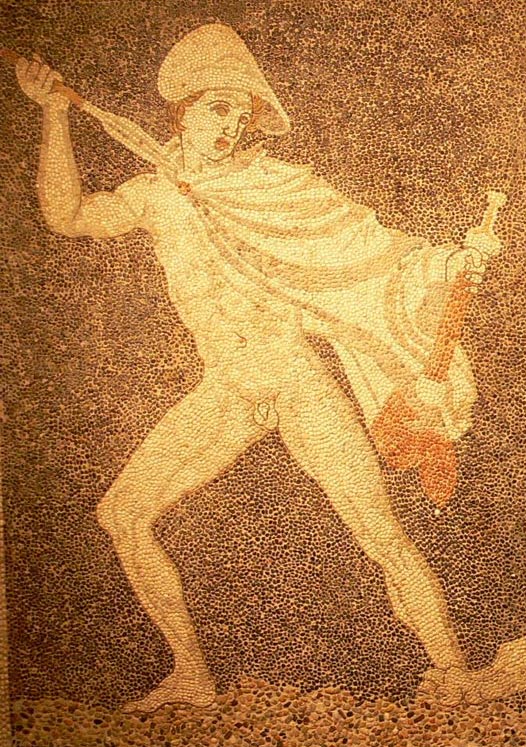

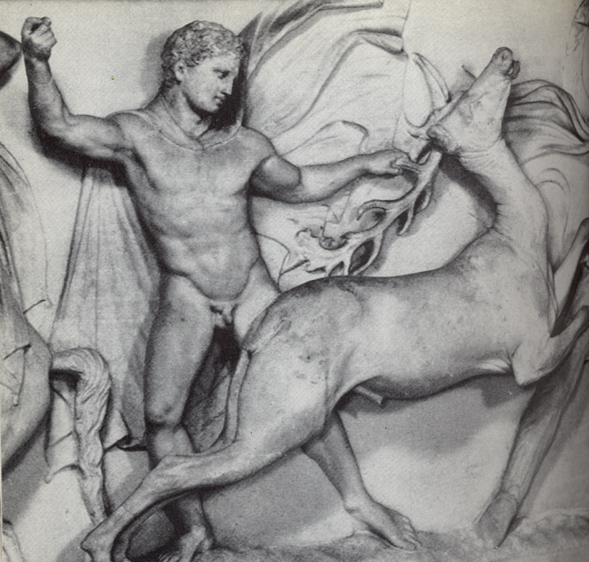

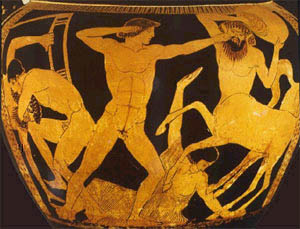

What I did, when I received that picture, was send back a reply with these two pictures:

To the ancients, that sort of nude hunting of a dangerous animal with

a Lover -- is righteous -- orthos.

And kalos -- morally beautiful in a Manly way.

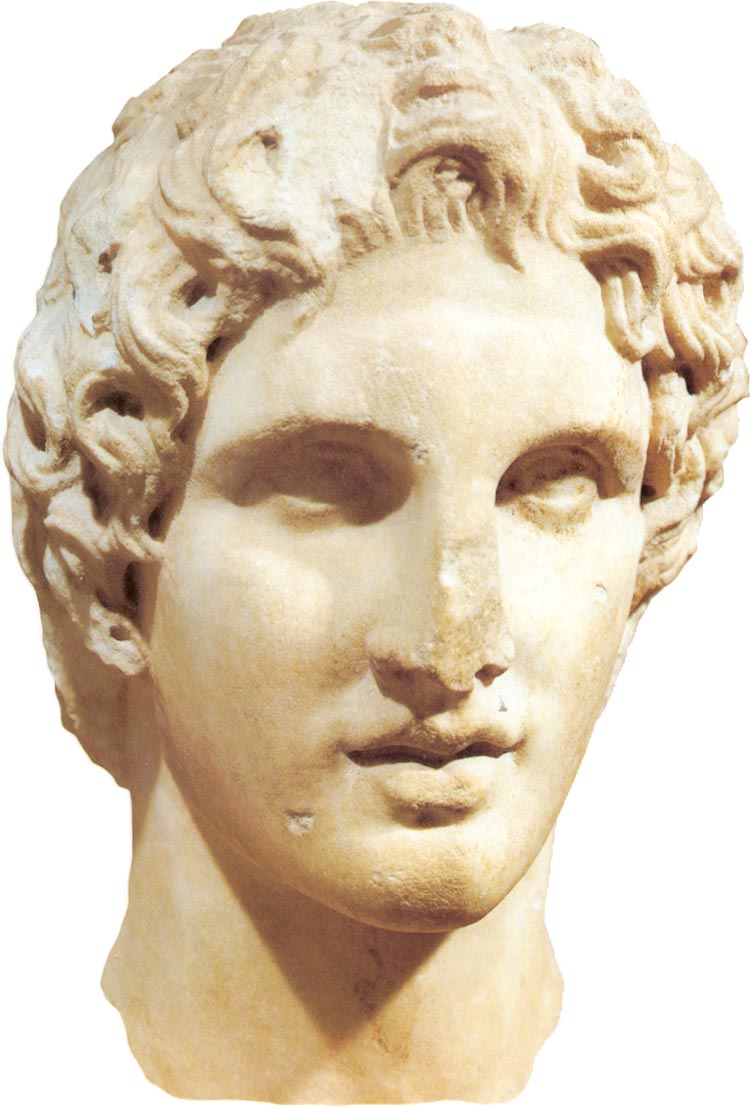

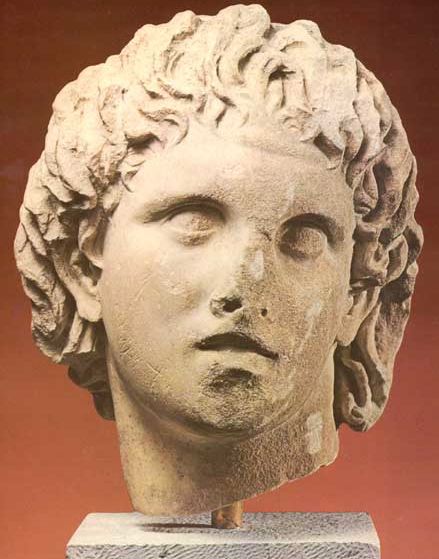

The other pic shows Alexander being saved on a lion hunt by his buddy Krateros.

What's happening is that Alexander has a spear, but he's not able to

get his sword out in time to strike a blow, and Krateros strikes the

lion, thus distracting him.

That too is orthos -- Righteous -- and Manly Morally Beautiful.

So -- Orthos has nothing to do with fucking pussy ;

Orthos, as Warrior NW said, years ago, is about the Man's Willingness and

Ability to Fight.

Whether the Fight is with a dangerous animal -- or another Man.

Which brings us to:

Once again, and as with orthos, this is not complicated.

If timé is Worth -- the Manly Worth which accrues to a Man through Prowess in Fighting -- then timé quickly reduces to -- Manhood.

And indeed, as we can see, there's a very close connection between timé -- and areté.

Because both are Manhood ; and more -- they're the Immortal Essence of Manhood.

Classicist Werner Jaeger:

Ambition [which is both "philo-timia" -- Love of Timé ; and Love of Areté -- is] the aspiration of the individual towards that ideal and supra-personal sphere in which alone he can have real value.

Areté exists in mortal man. Areté is mortal man. But it survives the mortal and lives on in his glory, in that very ideal of his areté which accompanied and directed him throughout his life.

Classicist JE Lendon, speaking of "the heroic code of the Greeks" and its logic:

"Always to be the best and to be pre-eminent above all others" was the aim of the heroes of the Iliad, and that aim was passed down the generations into later Greece, with only the respects in which an individual sought to excel changing over time.

Like our society, then, Greek society was competitive. But Greeks -- at least those of the upper classes, whose wealth freed them from want -- competed primarily not for money but rather for honor or glory; "worth," they called it, timé being the Greek word. Timé was how the Greeks ranked themselves against each other; to be the best was to possess the most timé, which consisted of esteem by others and others' confirmation of one's lofty impression of one's own merits. Still, timé was not merely soap bubble popularity or gaseous celebrity; timé was glory made palpable and somehow separate from its possessor. Timé was thought to have a real, almost physical existence, in the world: it could, for example, be taken from one man by another; it could be captured in war.

The quest for timé drove or touched much of what we think of as characteristic of ancient Greece. Competition in athletics was propelled by lust for timé, for games had been a source of glory since the days of Homer. Rivalry powered literature too; the dignified writer of Athenian tragedies waited anxiously to hear whether his was judged the best play of the festival. And, of course, Greeks from the age of Homer down sought timé especially in battle, for combat always remained the special arena "where men win glory."

The ceaseless search for pre-eminence in timé is on display especially in Greek names, which nearly all have boastful meanings. The Peloponessian War was populated by such characters as Pericles, "Very Glorious, " and his ward Alcibiades, "Son of Violent Strength," whose father was Cleinias, "Famous," and whose mother was Deinomache, "Terrible in Battle."

So -- timé is Worth, and most particularly the Worth which accrues to a Man through Prowess in Fighting, both in Nude Athletics -- Fight Sport -- and War -- which too was often Fought Nude.

And clearly, since much of the point, as Lendon makes plain, of going to war was to win timé, Nude Combat had to add to that timé.

In the Masculinist Society of ancient Greece, the Warriordom of ancient Greece, if male nudity had in any way detracted from timé -- it wouldn't have existed --

Not in daily life, in athletics, or in war -- because timé, like areté, to which it's obviously very closely related, was too important.

Clearly, then, Male Genital Nudity in Combat -- in Aggression -- *added* to the Man's timé -- to his Worth.

The Man who Fought Nude -- Gained Worth.

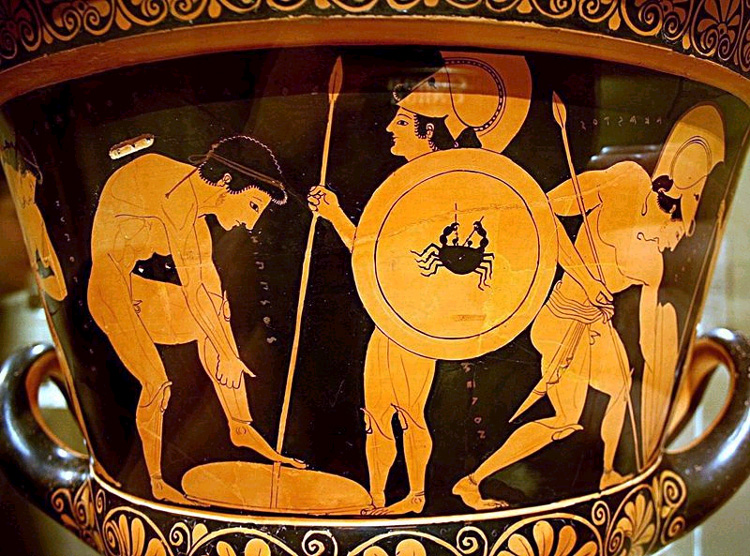

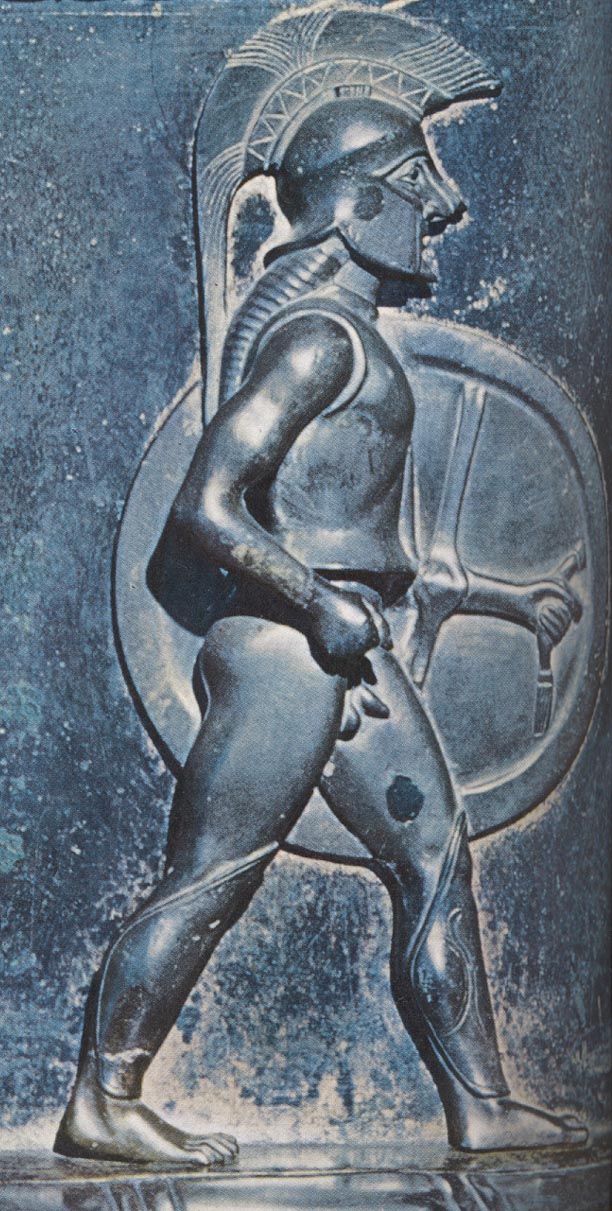

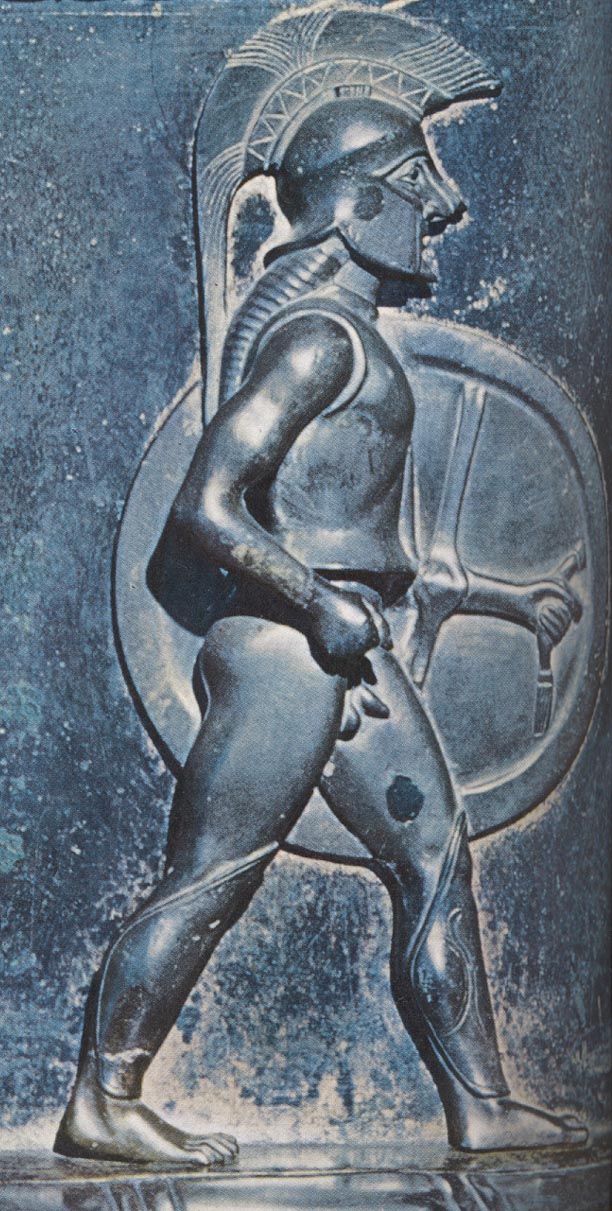

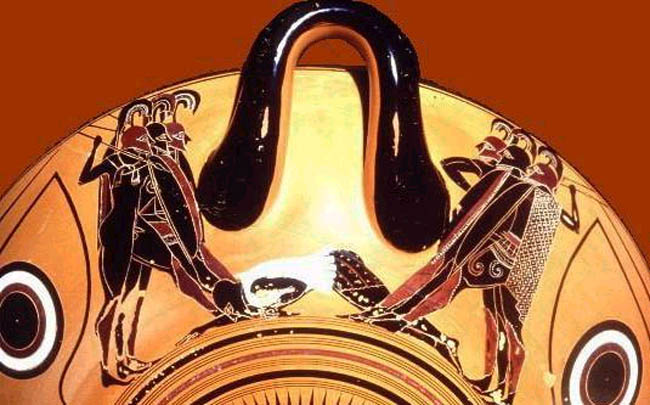

So -- here's a pic:

The guy on the left, about to hurl a stone, is a peltast, or lightly-armed soldier.

The guy in the middle is a hoplites --

So:

A Hoplites, or, in English, a Hoplite, was "a heavy-armed foot-soldier" who carried a large, round, shield.

And when we look at the picture, we see, occupying center stage, a hoplite -- who is, by the standards of his day, heavily and expensively armed, which makes him of higher social status than the peltast -- and, you'll notice, he's nude.

Nudity was common among all classes of ancient Greeks -- but it's telling that in this vase painting, the Man of higher social status -- is the Man who's Nude.

And certainly -- to the Spartans at least -- Manliness -- andreia -- was the province of hoplites -- because they Fought Man2Man -- Man Against Man.

Again, to the Spartans, the true test of a Man -- was hoplite battle.

As Lendon says,

Greek customs of warfare made fighting a test of personal excellence.

Heavy-armed were supposed to match their courage against other heavy-armed in the close grind of hand-to-hand combat.

Archers and javelin throwers were not supposed to take a decisive part, let alone stone throwers.

So -- what Lendon's saying is that to the Greeks, and especially the Spartans, "Fighting [was] a test of Personal Excellence."

And what is "Personal Excellence?"

It's Areté.

And what is Areté?

It's Manhood.

Fighting was a test of Manhood.

Lendon:

Heavy-armed [hoplites] were supposed to match their courage against other heavy-armed [hoplites] in the close grind of hand-to-hand combat.

So: Hoplites fought face-to-face -- the word for that in Greek is enantios --

Cf Latin adversus opposite, in opposition, facing, face to face with, against, in opposition to; thus, an enemy, an opponent

Hoplites fought face-to-face -- and hand-to-hand.

And to the Spartans, as to most of the other Greeks, that form of Fighting was the true test of Courage, and thus of

andreia -- Manhood, Manliness, Manly Spirit.

Lendon:

Heavy-armed were supposed to match their courage -- their Manhood -- against other heavy-armed in the close grind of hand-to-hand combat.

And notice the word "grind."

The Men ground against each other, shield again shield, helm against helm, chest against chest, groin against groin.

Just as we do.

Again:

Heavy-armed were supposed to match their courage against other heavy-armed in the close grind of hand-to-hand combat.

And what is "courage?"

Once again, it's andreia -- Manhood, Manliness, Manly Spirit.

Heavy-armed were supposed to match their Manhood against other heavy-armed in the close grind of hand-to-hand combat.

So:

The cultural ideal in this Masculinist Society was a match, a contest, a struggle and strife, of Manhood -- Fought Face-to-Face -- in the close Grind of Hand-to-Hand Combat.

Lendon:

Archers and javelin throwers were not supposed to take a decisive part, let alone stone throwers.

Why?

Because "fighting" from a distance -- by shooting an arrow, or throwing a stone -- was not manly.

It didn't require the same degree of andreia -- that Fighting hand-to-hand did.

But -- as Lendon explains, in the Peloponessian War, which pitted Athens and its allies against Sparta and its allies, the Athenians often violated andreia by using stone-throwers and archers -- males who "fought" at a distance -- against Spartan hoplites.

MEN who FOUGHT hand-to-hand.

Yet the Athenians were successful.

Often killing great numbers of Spartans in that way.

In discussing the Spartan surrender at Sphakteria, in which a Spartan force of hoplites was cut in two by archers and stone throwers, Lendon says,

Let's play that again:

Nor were the Athenians "stand-up" guys.

They weren't orthos -- they didn't stand erect to do battle.

Again, what is excellence?

It's Areté.

And what is Areté?

MANHOOD.

Which is what virtually all modern warfare is -- males shooting at each other, lobbing grenades at each other, dropping bombs, using drones -- from a distance.

"for the whole structure of honor in warfare had been cast down."

The whole structure of Honor -- which is Timé and To Kalon and Ta Kala and Areté --

Which is Manhood --

The whole structure of Manhood in Warfare -- had been cast down.

Here's Thukydides -- Lendon's source:

. . .

Now -- the word term translated as "men of honor" is "kaloi kagathoi" = kalos kai [and] agathos -- which is actually, in Greek, and as translated by Crawley in the nineteenth century -- and Crawley's translation is generally considered to be the best -- as "noble and good men."

And who are the noble and the good?

They're Men who are characterized by

If you don't understand that, please review the discussion of kalos and agathos.

Because kalos is nobility and beauty, nobility is selflessness, in particular the Warrior's selflessness in battle, the beauty is moral beauty -- that is, goodness -- and of course the first notion of goodness is Manhood;

while agathos is the adjectival form of areté -- meaning Manhood.

Again, that's how the words reduce and it's how they're used -- how they function, what they functionally mean.

On, and by the way --

The word the Spartan chose for "arrow" could also mean "spindle" -- the spindle used by women in spinning wool.

The Spartans had great contempt for arrows and those who used them.

So -- my little digression into Sphakteria -- was, yes, a digression, but highly germane to the question of Timé -- and Nude Combat.

Were the Spartans at Sphakteria nude?

I don't know.

But if they were nude, you can see why they would have been.

If, as Lendon says, and he's certainly correct, Greek warfare made Fighting a test of personal excellence -- of Manhood --

it would make perfect sense, and particularly in this period, when the Men were relatively lightly armored, for Spartan hoplites to Fight Nude.

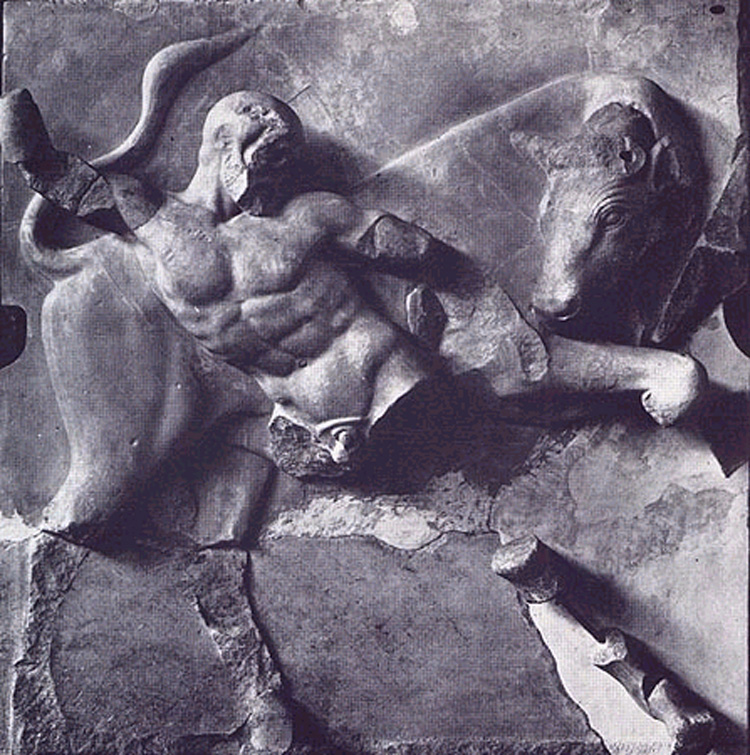

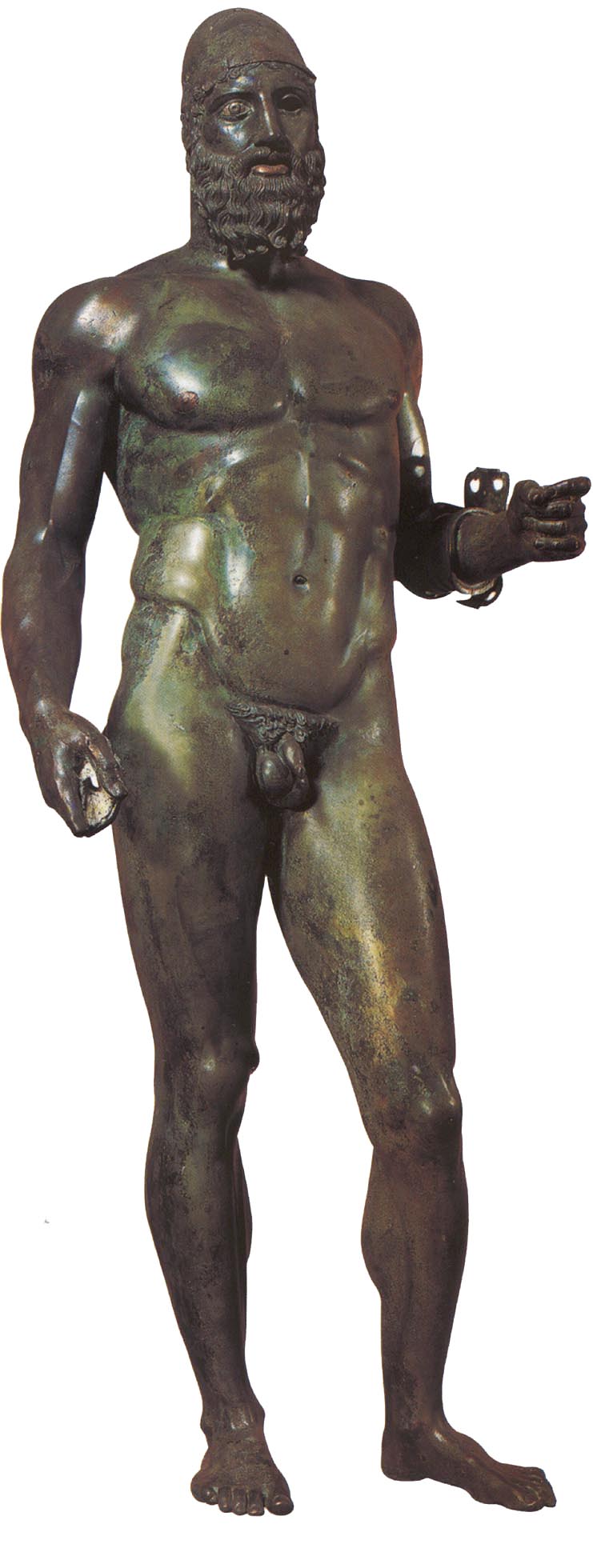

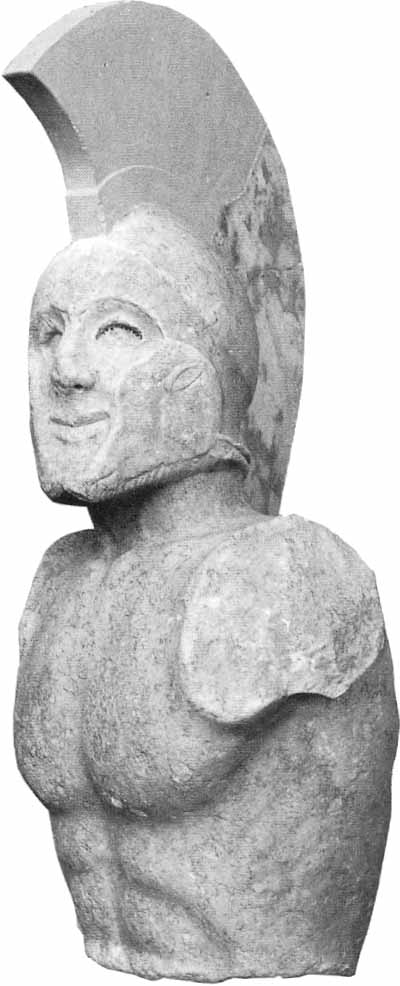

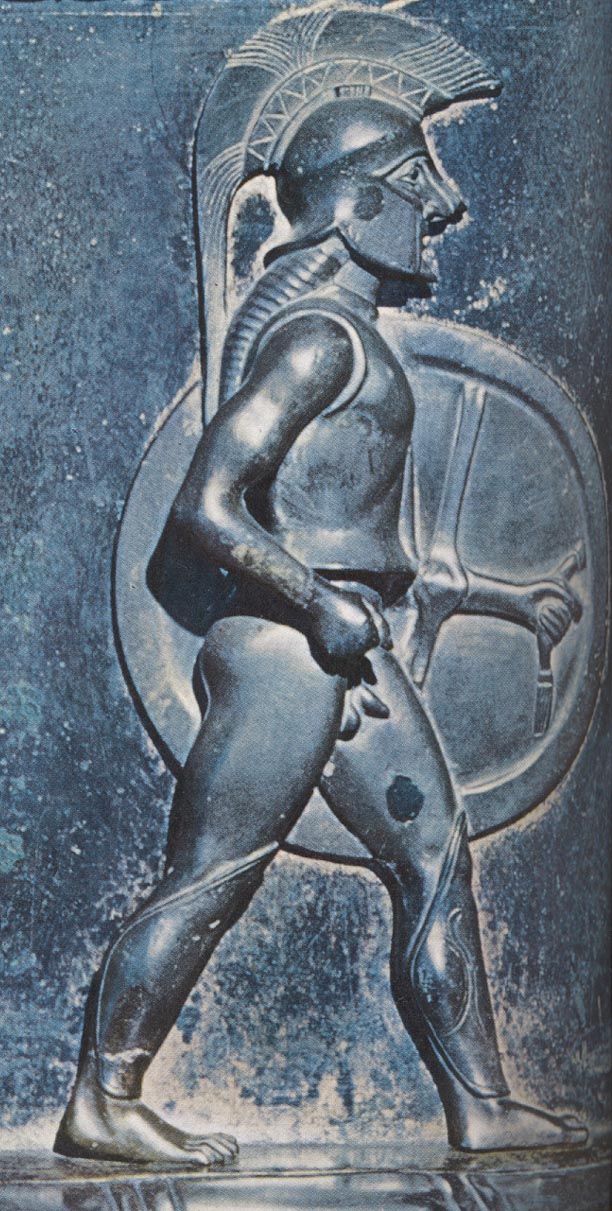

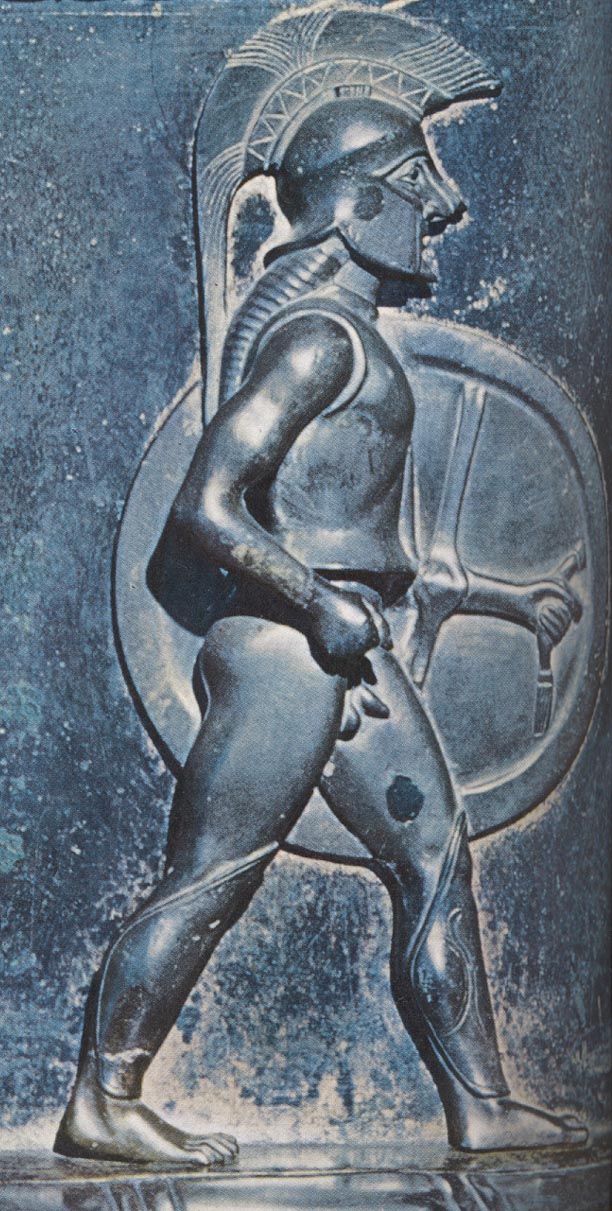

And here's an even better illustration -- this "helmet found at Dodona" depicts a Spartan culture-hero, Polydeukes, standing over a fallen foe:

Polydeukes, who was said to have invented boxing, carries the round hoplite shield and wears the very-revealing pilos helmet -- which, though the theme is mythological, puts the creation of this little masterpiece around the time of the Peloponessian War.

Polydeukes, by the way, was one of the two Dioskouroi, Loving Brothers and Spartan culture-heroes who exemplified, as another classicist says, the Spartan virtues of "piety, justice, military prowess, and courage" -- all attributes of Manhood.

And he's nude.

His one article of clothing is thrown off, so as to proudly display -- his Manhood.

Again:

If Men Fought Nude -- it had to *add* to Timé.

Why then did not Men always Fight Nude?

Why then, in war -- not in athletics, for athletics were *always* nude --

but why then, in war, were the genitals sometimes covered or protected by armour?

The answer, to me anyway, is plain: for tactical reasons.

As Lendon makes clear, the amount of armour worn varied over time as battlefield tactics shifted and changed.