The Secret Craft of Warriorhood

12-12-2010

"The secret craft of warriorhood" is a wonderful turn of phrase, a turn of phrase about Sparta, from classicist J E Lendon; and it can be found in his book Soldiers and Ghosts: A History of Battle in Classical Antiquity.

I've had Professor Lendon's book on my "save for later" list on amazon for more than a year.

I haven't had enough money to buy it.

And that's a problem.

Because my work is based both on my life-experience -- 62 years of being first a boy and then a Man who Loves Men -- and 38 years of advocating for those Men;

and on my research and reading.

So I have to have books.

And while you may feel that you've scored some sort of point by not donating and thus depriving me of a book -- as usual, the person being hurt is you.

Once again, you are, to borrow a word, *fabulously* self-impeding.

All that is to say that I don't own a copy of the book, and such being the case, I've read only a tiny portion of it on the amazon site.

But what I read was impressive indeed.

And once again "the secret craft of warriorhood" is an excellent turn of phrase, expressing as it does and so beautifully what the Spartans intended to teach their young.

So -- here are some excerpts from Prof Lendon's Soldiers and Ghosts: A History of Battle in Classical Antiquity:

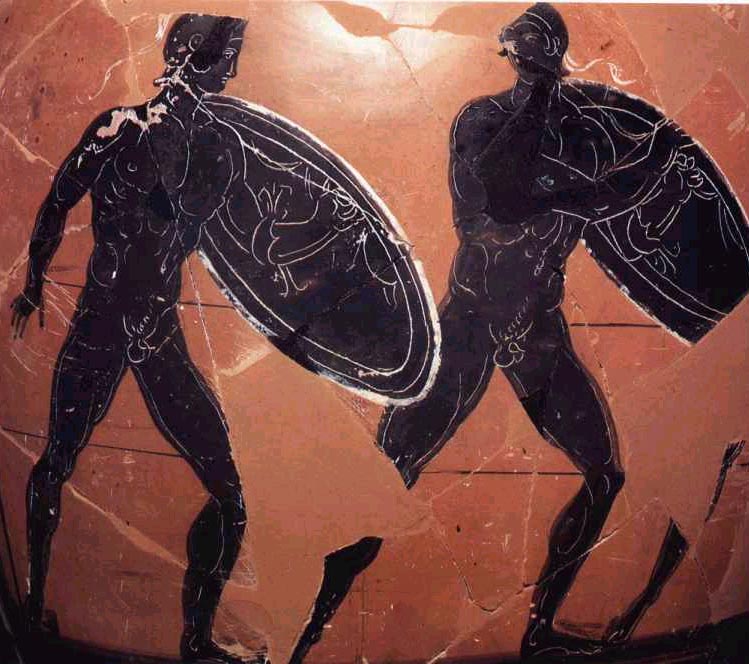

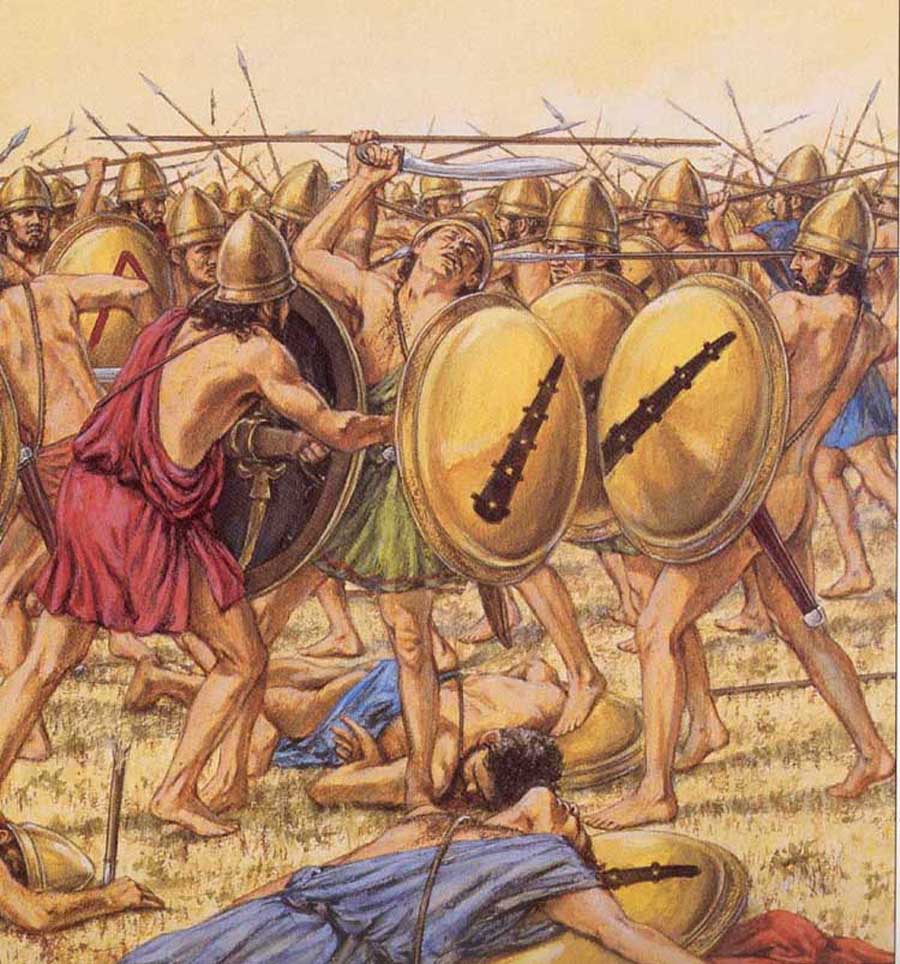

A peculiar quality of the Theban Sacred Band helps to explain this wider move towards training: the corps of three hundred, we are told, was made up of one hundred and fifty pairs of male lovers. Among the reported advantages of this arrangement was that of exaggerating competition among the warriors: lovers competed with each other and dreaded to be shamed in the presence of those they loved. Once again the competitive ethos of the hoplite emerges. But using such relationships between men as a font of military excellence is a transparent borrowing from Sparta, where such relationships were institutionalized, played a large role in the training of boys, and were thought to contribute to bravery in combat. At Sparta lover and beloved stood beside each other in the hoplite line; before battle the Spartans sacrificed to Eros, to love.

The idea for the trained Sacred Band, then, came from Sparta. "You'd think everybody else were mere improvisers in soldiering, and the Lacedaimonians the only artisans [technitai] of war," said Xenophon. Not only were the Spartans the most practiced in war, he is saying, but they seemed to him to envisage war as a techne, a learnable craft. . . . In Athens the legacy of Spartan success was experts in hoplite technique for hire; in Thebes, it was the trained Sacred Band of three hundred lovers.

. . .

. . . Spartans were open to the possibility, radical in the fifth century [BC], that physical courage itself was a consequence of training, rather than inborn. "Man differs little from man by nature, but he is best who trains in the hardest school," Thucydides has a Spartan king say. It is probably from the Spartans that intellectuals of the fifth and fourth centuries got the idea that courage was a function of experience or a mixture of training and inborn quality, an idea elaborated in philosophy into the doctrine that courage was a function of knowledge. . . .

. . .

[O]ne thing that set the Spartans apart from the other Greeks was their belief that many noble excellences could be taught, and their public care to see to it that they were. At seven a Spartan boy was taken from his mother and raised in barracks, beneath the eyes of older boys. Boys were whipped to inculcate respect (aidos) and obedience; they went ill-clad to make them tough; and they were starved to make them resistant to hunger. They were schooled to silence and taught to look at the ground while walking to train them in the supreme Greek civic virtue of self-control (sophrosyne). The cruel Spartan regime was believed to make Spartans brave. In short, as a frantic Athenian admirer of Sparta put it, "more men are excellent [agathos, the Homeric term] from practice than from nature."

. . .

To the Spartans hoplite training was not a low techne, but rather training in the secret craft of warriorhood. . . .

Spartan training in bravery, hoplite drill, and hoplite skill-at-arms was merely a subset of Spartan education of boys and young men, the old system of public upbringing (at whose origins we cannot guess), that notoriously set the Spartans apart from the rest of the Greeks. But being wrapped up tightly within that system, Spartan military training was not easy to imitate. . . .

So, guys, let's take a closer look:

A peculiar quality of the Theban Sacred Band helps to explain this wider move towards training: the corps of three hundred, we are told, was made up of one hundred and fifty pairs of male lovers. Among the reported advantages of this arrangement was that of exaggerating competition among the warriors: lovers competed with each other and dreaded to be shamed in the presence of those they loved. Once again the competitive ethos of the hoplite emerges.

"Once again the competitive ethos of the hoplite emerges."

Here, I would say, Prof Lendon is talking about the essentially competitive or agonal nature not just of the Hoplite, but of Greek life in general, and saying that it can be applied -- as does Werner Jaeger -- to male-male love.

Lendon:

lovers competed with each other and dreaded to be shamed in the presence of those they loved.

Jaeger:

It is, after all, easy to understand how a passionate admiration of noble bodies and balanced souls could spring up in a race which for countless years had prized physical prowess and spiritual harmony as the highest good attainable by man, and which had striven by grave and ceaseless rivalry, by exertion involving the utmost energies of mind and body alike, to bring those qualities to the greatest possible perfection.

Men who loved the possessors of those enviable qualities were moved by an ideal, the love for areté. Lovers who were bound by the male Eros were guarded by a deeper sense of honour from committing any base action, and were driven by a nobler impulse in attempting any honourable deed.

The Spartan state deliberately made Eros [male-male love] a factor, and an important factor, in its agogé.

So -- Jaeger speaks of Greek Men who had "had striven by grave and ceaseless rivalry, by exertion involving the utmost energies of mind and body alike, to bring those qualities [of physical prowess and spiritual harmony] to the greatest possible perfection" -- loving each other.

And says that Greek athletics are about "Men Struggling to bring their Manhood to Perfection."

Which strongly suggests -- and as you'll see when you read Prudence or the Pill, Xenophon confirms this -- that for the Greeks, as for so many of us, the beauty of guys was always tied and indeed should always be tied to aggression.

As Erich Segal points out in his Foreword to Waldo Sweet's Sport and Recreation in Ancient Greece.

Segal, who died not too long ago, is best known as the author of the saccharine Love Story.

But in real life he was a Harvard-educated classicist who taught at Yale.

In other words, a person of formidable erudition.

In his Foreword to Sweet's book, Segal notes that our word "sport" carries with it the sense of levity.

That's not true of the Greeks.

Their word, AGON, is the root of our word -- agony.

Which in Greek is agonia, and which means, first and foremost, a struggle for victory.

So an Agon is a Struggle, and the word Agon, says Segal, can "refer to encounters ranging from duels to debates."

Similarly, the Greek word athlos, from which we derive our word athletics, "could mean a contest taking place in a stadium or on a battlefield."

In ancient Greece, athletai could be rivals on the playing field or the battlefield.

Or, more properly, rivals in Fight Sport or in armed combat.

The Heracleitan idea -- which we'll discuss in a forthcoming post -- of "Strife as the Father of Everything" permeated Greek life.

Segal:

So -- Prof Lendon is no doubt right that Lovers -- and beloveds -- competed with each other to show who was the bravest.

Prof Lendon:

"using such relationships between men as a font of military excellence is a transparent borrowing from Sparta, where such relationships were institutionalized, played a large role in the training of boys, and were thought to contribute to bravery in combat. At Sparta lover and beloved stood beside each other in the hoplite line. . ."

And this is something I've said before, but I was delighted to see Prof Lendon confirming it:

That the Thebans had, essentially, stolen the idea of the Sacred Band from the Spartans.

Xenophon, the Athenian aristocrat and military man who more-or-less defected to the Spartans and, by virture of living in close proximity to them for years, seems to have understood them better than any of his other contemporaries, agrees, though he pooh-poohs the idea that Spartan lovers and beloveds have to be standing next to each other to be brave:

My own view is that those who assign these posts in battle suggest thereby that they are suspicious that the objects of their love, if left by themselves, will not perform the duties of brave men.

In contrast to this, the Lacedaemonians [Spartans], who hold that if a person so much as feels a bodily desire he will never know true nobility and goodness, cause the objects of their love to be so consummately brave that even when arrayed with foreigners and even when not stationed in the same line with their lovers they just as surely feel ashamed to desert their comrades. For the goddess they worship is not Shamelessness but Modesty [aidos].

~Xenophon, Symposion, 8.34, 35

Prof Lendon:

The idea for the trained Sacred Band, then, came from Sparta. "You'd think everybody else were mere improvisers in soldiering, and the Lacedaimonians the only artisans [technitai] of war," said Xenophon. Not only were the Spartans the most practiced in war, he is saying, but they seemed to him to envisage war as a techne, a learnable craft.

Right -- and just so you understand:

It's from the Greek work techne that we get our term "technical."

A techne is a skill, a craft, as Prof Lendon says, which can be learned.

Knowing how to build a ship -- or a house -- is a techne;

Knowing how to pilot a ship -- or manage an estate -- is a techne;

Architecture -- a techne.

You get the idea -- it's a distinct set of skills -- which can be taught.

Prior to the Peloponessian War (431 - 404 BC), however, only the Spartans actually sought to *teach* the arts of War -- they were, in effect, professional soldiers, while everyone else were amateurs.

When Sparta won the War, folks began re-thinking that question of amateur vs professional -- as Lendon says:

Prof Lendon:

. . . Spartans were open to the possibility, radical in the fifth century [BC], that physical courage itself was a consequence of training, rather than inborn. "Man differs little from man by nature, but he is best who trains in the hardest school," Thucydides has a Spartan king say. It is probably from the Spartans that intellectuals of the fifth and fourth centuries got the idea that courage was a function of experience or a mixture of training and inborn quality, an idea elaborated in philosophy into the doctrine that courage was a function of knowledge. . . .

Let's look at this sentence by sentence:

Why was that possibility "radical?"

Because of the connection, which I've often spelled out for you and which I will again, between and among:

In the fifth century, Ari-steia -- Heroism -- was thought to be a quality of the Ari-stocracy -- the "best" people.

And aristocracy, of course, was hereditary.

If aristocracy was hereditary, so was bravery.

But the Spartans, who were so often at war, couldn't afford to rest on their aristocratic laurels.

If Bravery could be taught -- then they would teach it.

Because, as King Agesilaus once said, Sparta needs Brave Men.

And the Spartan king in question is Archidamus -- father, by a second marriage, to King Agesilaus --

a buddy of Xenophon's and, actually, a Hero to him.

Which leads us to:

And, in my replies to posts like AJ's to feel my Manhood against his, I've quoted Xenophon to that effect -- saying that just as the body needs to be trained, so does the soul -- in the ways of Virtue.

Here's Xenophon, a contemporary of Plato's, a professional soldier, and a student of Sokrates:

. . .

To me indeed it seems that whatever is honourable, whatever is good in conduct is the result of training, and that this is especially true of prudence [self-control, temperance, moderation]. For in the same body along with the soul are planted the pleasures which call to her: "Abandon prudence, and make haste to gratify us and the body."

~Memorobilia, 1.1.19, 23.

"whatever is good in conduct is the result of training"

That's very different from saying it's the result of heredity -- what we would call good genes.

Not that the Spartans were opposed to "good genes" -- they invented eugenics after all.

So -- if a Man of good character and good physique wanted to fill the wife of a friend with his "noble sperm" and thus engender a child of good character -- and good physique -- the Spartans were all for it.

But -- they didn't leave anything to chance.

Once the child was born, provided he was a boy, he was headed for the agogé.

And some very serious soul-training.

Archidamus:

"Man differs little from man by nature, but he is best who trains in the hardest school."

Xenophon:

"Whatever is good in conduct is the result of training"

So you have to work at being Virtuous, you have to train the soul

just as you train the body.

Prof Lendon:

[O]ne thing that set the Spartans apart from the other Greeks was their belief that many noble excellences could be taught, and their public care to see to it that they were. At seven a Spartan boy was taken from his mother and raised in barracks, beneath the eyes of older boys. Boys were whipped to inculcate respect (aidos) and obedience; they went ill-clad to make them tough; and they were starved to make them resistant to hunger. They were schooled to silence and taught to look at the ground while walking to train them in the supreme Greek civic virtue of self-control (sophrosyne). The cruel Spartan regime was believed to make Spartans brave. In short, as a frantic Athenian admirer of Sparta put it, "more men are excellent [agathos, the Homeric term] from practice than from nature."

"[O]ne thing that set the Spartans apart from the other Greeks was their belief that many noble excellences could be taught, and their public care to see to it that they were."

Among those many noble excellences were, of course, the Divine Virtures: Piety / Holiness / Sanctity, Courage, Self-Control, Justice, and Wisdom.

And you'll notice that Prof Lendon describes self-control as "the supreme Greek civic virtue."

Which is certainly correct.

Self-control -- sophrosyne -- is, like areté and agon, a key concept among the Greeks.

And in the list of Divine Virtues, it often occupies the third, or pivotal, place:

These, the Spartans believed, could and should be taught, and taught by the State:

"At seven a Spartan boy was taken from his mother and raised in barracks, beneath the eyes of older boys. Boys were whipped to inculcate respect (aidos) and obedience; they went ill-clad to make them tough; and they were starved to make them resistant to hunger. They were schooled to silence and taught to look at the ground while walking to train them in the supreme Greek civic virtue of self-control (sophrosyne). The cruel Spartan regime was believed to make Spartans brave. In short, as a frantic Athenian admirer of Sparta put it, "more men are excellent [agathos, the Homeric term] from practice than from nature."

Now:

Prof Lendon says this training, this agogé, was a "cruel" regime.

Is that true?

Well, possibly to present-day Americans -- though I must say, given its purpose, it dosesn't seem so to me -- and it certainly wouldn't have been to the Greeks.

First of all, many elements of the agogé were present in child-rearing practices in the other states too -- they just weren't as systematized.

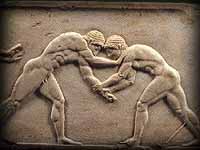

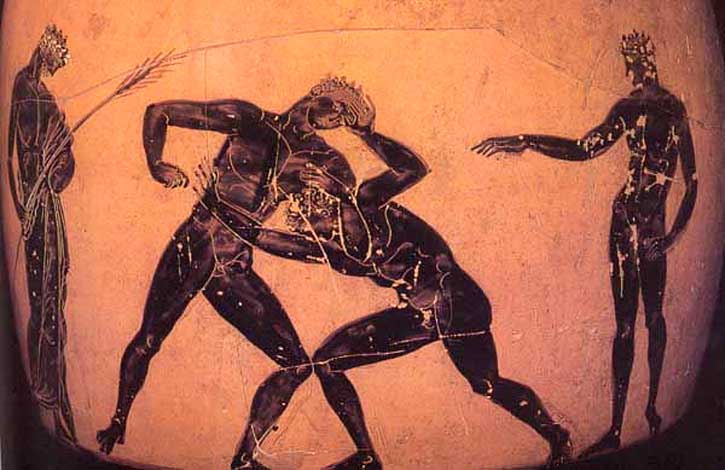

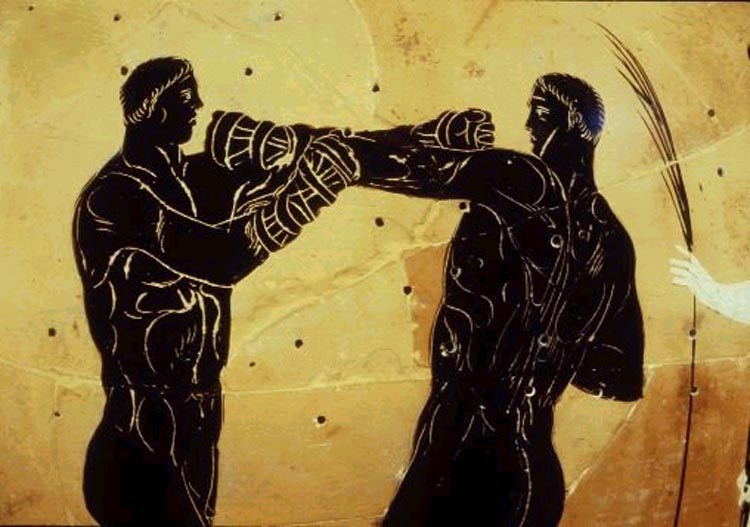

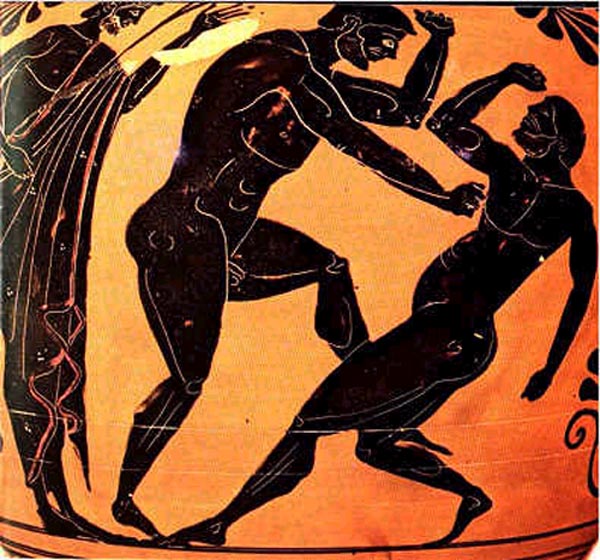

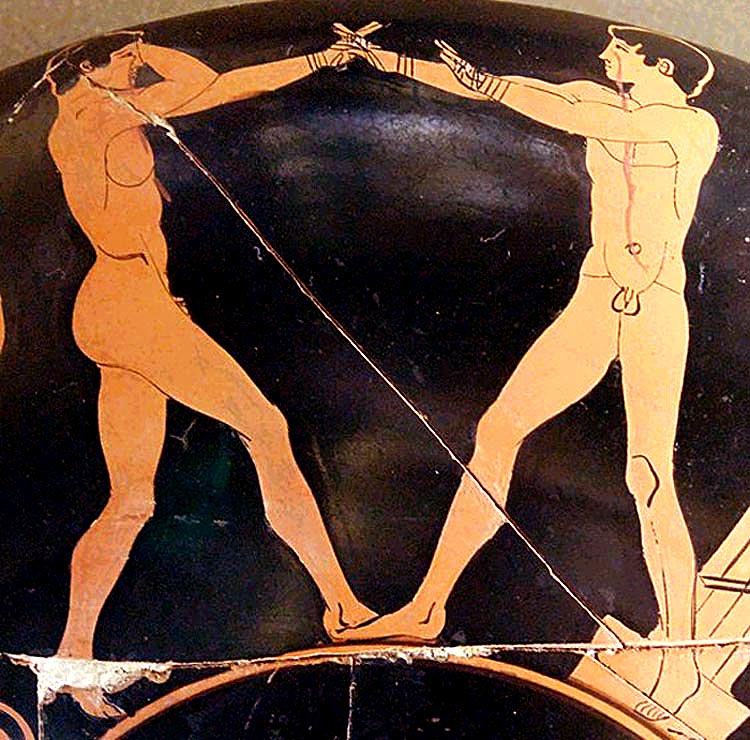

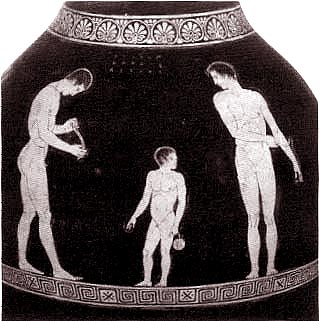

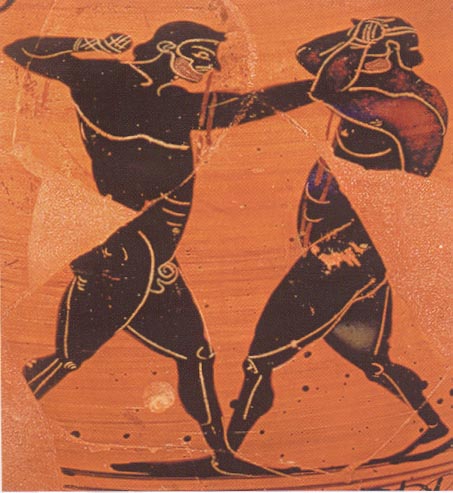

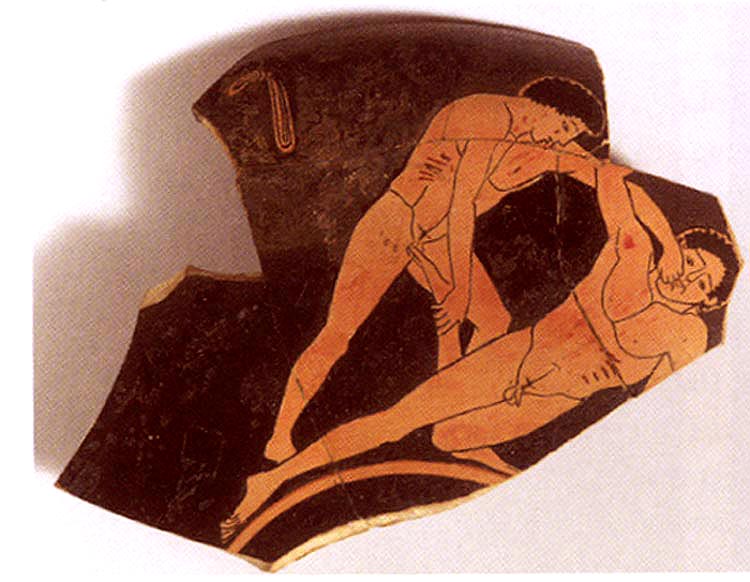

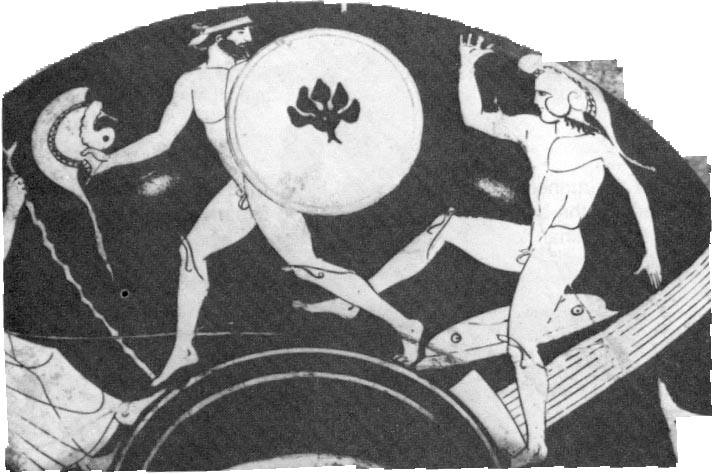

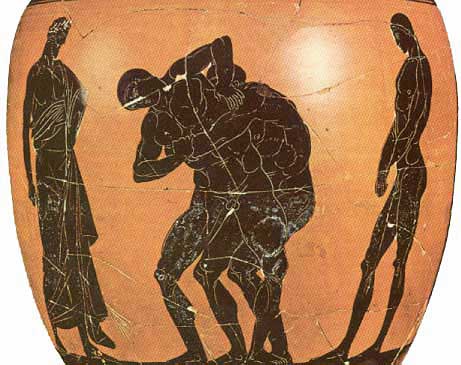

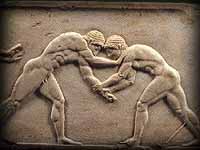

For example, the physical training in Fight Sport which the kids received at the Palaistra -- which wasn't just wrestling, but boxing and pankration too -- was rough -- at least to our eyes -- everywhere.

To the Greeks it was necessary.

So, in a first century AD Dialogue written by Lucian, but purporting to present an imagined conversation between the *sixth century BC* Athenian lawgiver Solon and a Scythian visitor to Athens named Anacharsis, we hear the following:

As for physical training, which you particularly wanted to hear about, we proceed as follows. When the boys reach an age when they are no longer soft and uncoordinated, we strip them naked. We do this because first, we think they should get used to the weather, learning to live with different seasons, so they are not bothered by the heat nor do they yield to the cold. . . .

Next we have thought up different kinds of athletics and have appointed coaches for each type. We teach one how to box, another how to compete in the pankration, so that they can become used to hard work, to stand up to blows face to face, and not to yield through fear of injury.

This creates two valuable traits in our young men: it makes them brave in the face of danger and unsparing of their bodies, and it also makes them strong and vigorous. Those who wrestle and push against each other learn how to fall safely and spring up nimbly, to endure pushing, grappling, twisting, and choking, and to be able to lift their opponent off the ground. They are not learning useless skills but they get the one thing which is the first and most important thing in life: through this training their bodies become stronger and capable of enduring pain.

There is another thing too which is not unimportant. From this training they acquire skills which they may need some day in war. For it is clear that if a man so trained grapples with an enemy, he will trip and throw him more quickly and if he is thrown he will know how to regain his feet as easily as possible. For we prepare our men, Anacharsis, for the supreme contest, war, and we expect to have much better soldiers out of young men who have had this training, that is, the previous conditioning and training of naked bodies, which makes them not only stronger and healthier, more agile and fit, but also causes them to outweigh their opponents.

We train them to run, getting them to endure long distances as well as

speeding them up for swiftness in the sprints.

This running is not done on a firm springy surface but in deep sand, where it is not easy to place one's foot forcefully and not to push off from it, since the foot slips against the yielding sand. We train them to jump over ditches, if they have to, or any other obstacles, and in addition we train them to do this even when they carry lead weights as large as they can hold. They also compete in the javelin throw for distance. In the gymnasium you also saw another athletic implement, bronze, circular, like a tiny shield with no bar or straps. You handled it as it lay there and expressed the view that it was heavy and hard to hold on to because it was so smooth. Well, they throw this up in the air both high and out, competing to see who can throw the longest and pass beyond the others. This exercise strengthens the shoulders and builds up the arms and legs.

As for this mud and dust [used in training in wrestling and other Fight Sports], which originally seemed so amusing to you, my

friend, listen while I tell you why it is used. First, their fall will not be on unyielding dirt but they will fall safely on soft ground. Next, their slipperiness has to be greater when they sweat in the mud. You likened them to eels, but the facts are neither useless nor humorous: it adds not a little to strength of the sinews when they are forced to hold firmly to people in this condition when they are trying to slip away. Do not think it is easy to pick up a sweaty man in the mud, covered with oil and trying to get out of your arms. All these skills, as I said earlier, are useful in combat, if it were necessary to pick up a wounded friend and carry him easily to safety or to seize an enemy and bring him back in your arms. And for this reason we train them beyond what is necessary, so that when they have practiced hard tasks they may do smaller ones with much greater facility.

We believe the dust is used for the opposite reason than the oil is, that is, so that a competitor may not slip out of his opponent's grasp. For after they have been trained in the mud to hold fast to something which is escaping from them because of its slipperiness, they then practice escaping out of the arms of their opponent, no matter how impossibly firm they may be held.

I should dearly like to stand one of those white-skinned fellows who live in the shade beside one of our boys who work out in the Lykeion, and after I had washed off the dust and the mud, ask you which one you would like to resemble. For I know that you would choose at first glance, without hesitation, even without putting either through any tests, the one which is solid and hard

rather than soft, weak, and pale, because what little blood he has has been withdrawn into the interior of his body.

[Anacharsis then ridicules the idea that athletic training could be useful in war. Why not save your strength, he asks. Solon explains that strength cannot be saved like a bottle of wine; it must be constantly used.]

Anacharsis: I just don't understand what you said, Solon. It is too intellectual for me and requires a sharp mind and keen insight. But above all, tell me this, why, in the Olympic Games and at Isthmia and Delphi and elsewhere, where so many competitors, you say, assemble to see these young men compete, you never have a contest with weapons but you bring them before the spectators all naked and exhibit them getting kicked and punched, and then, if they have won, give them berries and wild olives? It would be worth knowing why you do this.

Solon: My dear Anacharsis, we do this because we think that their enthusiasm for athletics will increase if they see that those who excel at them are honored and are presented to crowds of Greeks by heralds. Because they are to appear stripped before so many people, they try to get into good condition, so that when they are naked they will not be ashamed, and each one works to make himself capable of winning. As for the prizes, as I said earlier, they are not insignificant: to be praised by the spectators, to be a recognized celebrity, and to be pointed out as the best of one's group. As a result of these prizes, many of the spectators who are of the right age for competition go away completely in love with courage and struggle. If someone should remove love of glory from our lives, what good would we ever achieve, Anacharsis, or who would strive to accomplish some shining deed? But now it is possible for you to imagine from these games what sort of men these would be under arms, fighting for fatherland and children and wives and temples, when they show so much desire for victory in competing for laurel berries and wild olives.

Furthermore, how would you feel if you should observe fights between

quails and between roosters here among us, and see the great interest

which is shown in them? Wouldn't you laugh, particularly if you should learn that we do this in accordance with our laws and all men of military age are instructed to be present and to see these birds fight until they are exhausted? But it is no laughing matter, for eagerness for danger creeps insensibly into their souls so that they try not to seem less courageous and bold than the roosters nor to give in too soon because of injury or fatigue or any other distress.

As for trying them in armed combat and seeing them receive wounds --

never! It is brutal and dreadfully wrong, and in addition it is economically unfeasible to destroy the bravest, whom we could better use against our enemies.

Since you tell me, Anacharsis, that you expect to travel to the rest of

Greece, if you get to Sparta, remember not to laugh at them nor think that they have no purpose when they compete in a theater, rushing together and striking each other, fighting over a ball, or when they go into a place surrounded by water [known as Plantanistas, or Plane-Tree Grove], choose up sides, and fight as if in actual war, although as naked as we Athenians are, until one team drives the other out of the enclosure into the water, the Sons of Herakles beating the Sons of Lykurgos or vice versa; after this contest there is peace and no one would strike another.

~Translated by Sweet.

And if you'd like to read more of this dialogue, which, whether you're into Fight Sport, or just into Men and Manliness, I strongly recommend you do, you can find the rest of it by clicking here, or simply scrolling to the bottom of this page.

So:

Solon says that when the boys are old enough, they're stripped naked and made to train naked:

"so they are not bothered by the heat nor do they yield to the cold."

In other words, through nudity they learn endurance in the face of the weather -- just like the kids in Sparta.

Indeed, it's the Spartans who were believed to have invented nude exercise:

The Spartans were the first to exercise gymnoi [nude] and to disrobe in public and rub themselves with olive oil after they had exercised while gymnoi.

~ Thucydides

So nudity, the Greeks believed, was originally a Spartan practice.

Which in this case has been taken up by Athenian youth.

Who are then taught various types of fight sports:

"We teach one how to box, another how to compete in the pankration, so that they can become used to hard work, to stand up to blows face to face, and not to yield through fear of injury."

"to stand up to blows face to face, and not to yield through fear of injury"

Those are extremely important lessons.

Which were not just taught at Sparta, but which the Spartans were also said to have invented:

~Philostratos, On Gymnastics

Solon:

"This creates two valuable traits in our young men: it makes them brave in the face of danger and unsparing of their bodies, and it also makes them strong and vigorous."

They're also taught what we'd call track and field, which to Solon have military utility.

And they're trained to wrestle and fight in both mud and dust, so that they can deal with an opponent either who is slippery or who can grasp them tightly.

Solon then makes a point that most modern coaches would agree with:

"Strength cannot be saved like a bottle of wine; it must be constantly used."

As to the great religious-athletic festivals, says Solon, "we think that the enthusiasm [of our youths and young men] for athletics will increase if they see that those who excel at them are honored and are presented to crowds of Greeks by heralds. Because they are to appear stripped before so many people, they try to get into good condition, so that when they are naked they will not be ashamed, and each one works to make himself capable of winning. As for the prizes, as I said earlier, they are not insignificant: to be praised by the spectators, to be a recognized celebrity, and to be pointed out as the best of one's group. As a result of these prizes, many of the spectators who are of the right age for competition go away completely in love with courage and struggle."

To create youth who are "completely in love with courage and struggle."

That's an important goal.

And it's one which was pursued at Sparta too.

And more than that.

Because it's safe to assume that just as the Sacred Band of Thebes was, in Professor Lendon's words, "a transparent borrowing from Sparta," so was much of the training which Lucian / Solon describes at Athens:

The nudity, the ability "to stand up to blows face to face, and not to yield through fear of injury," and the use of nude public competitions and peer and other societal pressure to produce youths who were "completely in love with courage and struggle."

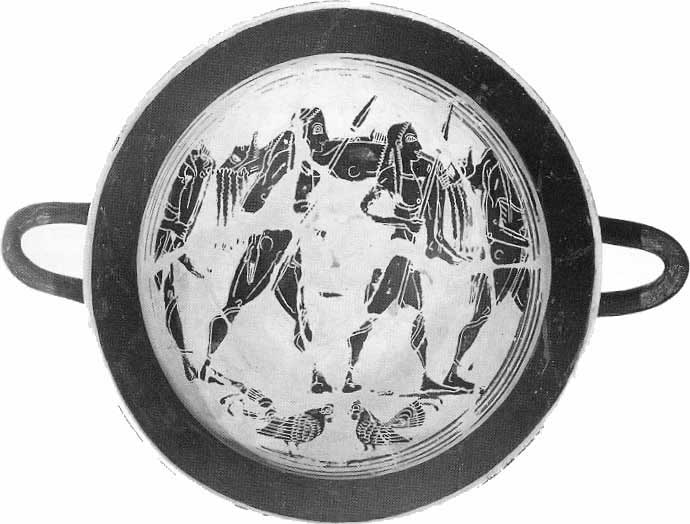

Then Solon talks about cockfighting -- that is, fighting between roosters -- which all the boys and Men are made to watch as an object-lesson: "for eagerness for danger creeps insensibly into their souls so that they try not to seem less courageous and bold than the roosters nor to give in too soon because of injury or fatigue or any other distress."

~Plutarch, Sayings of the Spartans

And Solon ends with a description of the various forms of organized fighting at Sparta, in particular the Fighting of the Youths at Plane-Tree Grove -- a very important part of the Agogé and its Strife of Valour.

Of which he says:

And we know that at Sparta, such organized fights between rival teams continued into young adulthood.

But of course the bulk of Solon's description is of Athens, not Sparta.

The difference being that at Sparta, boys were taken from their parents at age seven and raised in small troops known as Boua, which translates as herds or herds of bull-calves.

They were made to live in these small, all-male groups, constantly out of doors; to be naked virtually all of the time -- not just when exercising; and to fend for themselves in many ways.

At the same time, they were under the supervision of older boys, and of the adult male Spartans, the Spartan Peers or Equals.

Any one of whom could intervene in their training, and indeed was expected too.

So the boys had, in that sense, not just one father, but literally thousands of fathers.

And there was one Man, chosen for his noble, good, and brave spirit, who supervised the entire educational effort.

And certainly part of the purpose of the Agogé was, to quote Solon, to create a group of fighting youths "completely in love with courage and struggle."

But it was more than that.

It was also to create a Warriorhood -- a brotherhood of Warriors -- in which, as the Encyclopedia Britannica says, a system of male-male pair-bonding created hoplite bonds of ferocious intensity.

So -- the Spartan system was not, given the way boys were trained in other Greek city-states, particularly cruel.

Furthermore, many non-Spartan Greeks sent their kids to Sparta and had them enrolled in the agogé --

among them Xenophon, both of whose sons were raised in the agogé.

Nor is there any evidence in Plutarch's Lives of two Spartans -- Agesilaus and Lysander -- that the agogé was thought to be unusually harsh.

This is from Plutarch's Life of Agesilaus:

During the year that he spent in one of the companies [herds] of boys who were brought together under the Spartan system, he had as his lover [the great Spartan general] Lysander, who was especially struck by his natural modesty and discretion. Agesilaus was more aggressive and hot-tempered than his companions. He longed to be first in all things, and he had in him a vehemence and impetuosity which were inexhaustible, and carried him over all obstacles; yet at the same time he was so gentle and ready to obey authority that he did whatever was demanded of him. He acted in this way from a sense of honour, not of fear, and he was far more sensitive to rebuke than to any amount of hardship. He was lame in one leg, but the beauty of his physique in the prime of his youth made the deformity pass almost unnoticed, and the ease and light-heartedness with which he endured it went far to compensate for the disability, since he was the first to joke and make fun of himself on this subject. In fact his lameness served to reveal his ambition even more clearly, since he never allowed it to deter him from any enterprise, however arduous it might turn out. ...

And this is what Plutarch says of Lysander's boyhood:

Indeed, from the very first the Spartans wish their boys to be sensitive toward public opinion, distressed by censure, and exalted by praise; and he who is insensible and stolid in these matters, is looked down upon as without ambition for excellence, and a cumberer of the ground. Ambition, then, and the spirit of emulation, were firmly implanted in Lysander by his Laconian training and and no great fault should be found with his natural disposition on this account.

Doesn't sound bad to me.

The kids were taught to be aggressive, and to excel, but also to obey, not out of fear, but out of sensitivity to rebuke -- which is basically a communal value.

They were encouraged to express their Manly spirit, and to be "superior to every pleasure," "sensitive toward public opinion, distressed by censure, and exalted by praise" --

and to be, above all, motivated by the ambition to excel -- that is, to display areté, Manly Excellence.

Plutarch:

~ Life of Lycurgus, translated by Talbot

And that was all part of the Spartan ethos, which ranked Men not by wealth, but by Valour.

As one authority has said:

So -- the rigors of the Spartan system, of the agogé, provided Men with a life of "a life of discipline, self-denial, and simplicity."

It was a regime of austerity and equality.

And it was a government, as Plato said, of Honour.

"The Spartan . . . could point to Spartan society and argue that moral values and human courage and strength was as great as it was before civilization."

And the other Greeks admired that.

As Jaeger has said:

So -- the Spartan system, the agogé, was greatly respected by the other Greeks.

Nor do we hear of Spartans defecting from Sparta because they don't want to go or they don't want their kids to go through the agogé

Indeed, there's no evidence that Spartans were not happy living at Sparta.

Plutarch paints the opposite picture:

So -- the Spartans had

Sounds great!

So -- life in fifth and fourth century BC Greece was, by our standards, harsh and in many respects cruel.

And one of the cruelest was the plain fact that to lose in war was to run the risk of being either killed or enslaved.

The Spartan system was designed to make their boys into Warriors who would be victorious in War -- and thus remain both alive and Free.

And it was a system:

Prof Lendon:

To the Spartans hoplite training was not a low techne, but rather training in the secret craft of warriorhood. . . .

Spartan training in bravery, hoplite drill, and hoplite skill-at-arms was merely a subset of Spartan education of boys and young men, the old system of public upbringing (at whose origins we cannot guess), that notoriously set the Spartans apart from the rest of the Greeks. But being wrapped up tightly within that system, Spartan military training was not easy to imitate. . . .

So -- it was a system, and a complex system, carefully thought through, and not easy to just casually imitate.

Now: Professsor Lendon says

To the Spartans hoplite training was not a low techne, but rather training in the secret craft of warriorhood. . . .

Why "secret"?

Because the Spartans were secretive.

It was military training after all, and most militaries rely on secrets to give them an edge over their enemies.

So did the Spartans.

The Spartans sought to keep many elements of Spartan society secret from their fellow Greeks.

That we know as much as we do about them is due to their Athenian admirers, such as Aristides and Cimon and Sokrates, Plato, and Xenophon --

and to Plutarch, who wrote about them in the late first and early second centuries AD, when Sparta was no longer a military power and its secrets, therefore, no longer needed to be kept.

Still, "the secret craft of Warriorhood" expresses -- brilliantly -- what the Spartans were about;

and what all MEN should be about:

Mastering the Secret Craft of Warriorhood.

Bill Weintraub

December 12, 2010

© All material Copyright 2010 by Bill Weintraub. All rights reserved.

and AND

Warriors Speak is presented by The Man2Man Alliance, an organization of men into

Frot

To learn more about Frot, ck out What's Hot About Frot

Or visit our FAQs page.

© All material on this site Copyright 2001 - 2011 by Bill Weintraub. All rights reserved.

It was my own innate understanding of the essentially Combative and Aggressive nature of Men, and my own instinctual relating of that to the testicles, which produced those fantasies and gave them so much power in my life.

In this Dialogue, written in the first century AD by Lucian but presenting an imagined conversation between the *sixth century BC* Athenian lawgiver Solon and a Scythian visitor to Athens named Anacharsis, we get some idea of what that training was like -- starting with Athenian kids, and then progressing to Spartan youth:

Anacharsis: And another thing, my dear Solon, why are those young men

acting in this way? Look, some of them are grappling and tripping each

other, others are choking their friends and twisting their limbs, rolling about in the mud and wallowing like pigs. But before they began to do this, I noticed they first took off their clothes, then put oil on themselves, and in a peaceful fashion took turns in rubbing each other. But now, experiencing some emotion I do not understand, they have lowered their heads and are crashing into each other, and butting their heads together like rams! And look! There is one who has just seized the other by the legs and thrown him down; then he flopped on him and did not allow him to get up, but shoved him down into the mud. And now he is finally twisting his legs around the other person's waist and choking him with his arm under his throat. The other is slapping him on the shoulder, trying to ask him, I suppose, not to choke him to death. They do not avoid getting covered with dirt even to save the oil, but on the contrary wipe it off, and smearing themselves with mud and rivers of perspiration they make themselves ridiculous, in my opinion, by sliding in and out of each other's hands like eels.

Others are acting in the same way in the open part of the courtyard.

However, these are not in the mud, but they have this deep sand in the pit which they sprinkle on themselves and each other, just like roosters, so that they cannot break out of their grasp, I imagine, since the sand decreases the slipperiness and offers a surer grip on a dry skin.

Others also covered with dust are standing up straight and striking and

kicking each other. See that one there! Poor fellow, he seems to be ready to spit out a mouthful of teeth considering how full of blood and sand his mouth is; he has got a blow to the jaw, as you can see for yourself. But the official there does not separate them and stop the fight -- at least I assume he is an official from his scarlet cloak. On the contrary he encourages them and cheers the one who struck that blow.

All around different people are all exercising: some raise their knees as if running, although they remain in the same place, and as they jump up they kick the air.

What I want to know is, what reason do they have for doing this? It seems to me these actions are almost insane, and there is no one who can easily persuade me that people who act like this have not lost all their senses.

[Solon explains that customs differ from one land to another. He then explains to Anacharsis what is happening.]

Solon: This place, dear Anacharsis, is what we call a gymnasion and it and is sacred to Lykeian Apollo. You can see his statue, leaning against a stele, holding his bow in his left hand. His right arm is bent above his head as if the artist were showing the God resting, as if he had completed some laborious task. As for those exercises in the nude, the one done in the mud is called wrestling. Those in the dust are also wrestling. Those who strike each other standing upright we call pankratiasts. We have other athletic events: we have contests in boxing, diskos, and the long jump, and the winner is considered superior to his fellows and takes the prize.

Anacharsis: These prizes of yours now; what are they?

Solon: At Olympia there is a crown of wild olive; at Isthmia, one of pine; at Nemea, one woven of celery; at the Pythian Games, laurel berries sacred to the god, and here at home at the Panathenaic Games, oil from olive trees which grow in the sacred precincts. What are you laughing at, Anacharsis? Do these prizes seem valueless to you?

[Solon explains the symbolic value of the prizes, justifies the pursuit of athletics, the education of the citizens. Then Anacharsis asks Solon to explain the government of Athens.]

Solon: It is not easy, my friend, to explain everything at once in concise form, but if you will take one thing at a time you will learn everything about our belief in the gods, as well as our attitude toward parents, marriage, or anything else.

I will now explain our theory about young men and how we treat them from the time when they begin to know the difference between right and wrong and are entering manhood and sustaining hardships, so that you may learn why we require them to undergo these exercises and force them to subject their bodies to toil, not just because of the athletic games and the prizes they may win there, for few of them have the ability to do that, but so that they may try to gain a greater good for the entire city and for themselves. For there is another contest set up for all good citizens and the crown is not made of pine nor of wild olive nor of celery, but is one which includes all of man's happiness, that is to say, freedom for each person individually and for the state in general: wealth, glory, pleasure in our traditional feast days, having the entire family safe from harm, and in a word, to have the best of all the blessings one could have from the gods.

All this happiness is woven into the crown to which I referred and is acquired in the contest to which these exhausting exercises lead.

[Solon goes into more detail about the training of young men and about the responsibility of the citizens.]

Solon: As for physical training, which you particularly wanted to hear about, we proceed as follows. When the boys reach an age when they are no longer soft and uncoordinated, we strip them naked. We do this because first, we think they should get used to the weather, learning to live with different seasons, so they are not bothered by the heat nor do they yield to the cold. Then we massage them with olive oil and condition the skin. For since we see that leather which is softened by olive oil does not easily crack and is much stronger, even though it is not alive, why should we not think that live bodies would benefit from oil? Next we have thought up different kinds of athletics and have appointed coaches for each type. We teach one how to box, another how to compete in the pankration, so that they can become used to hard work, to stand up to blows face to face, and not to yield through fear of injury.

This creates two valuable traits in our young men: it makes them brave in the face of danger and unsparing of their bodies, and it also makes them strong and vigorous. Those who wrestle and push against each other learn how to fall safely and spring up nimbly, to endure pushing, grappling, twisting, and choking, and to be able to lift their opponent off the ground. They are not learning useless skills but they get the one thing which is the first and most important thing in life: through this training their bodies become stronger and capable of enduring pain. There is another thing too which is not unimportant. From this training they acquire skills which they may need some day in war. For it is clear that if a man so trained grapples with an enemy, he will trip and throw him more quickly and if he is thrown he will know how to regain his feet as easily as possible. For we prepare our men, Anacharsis, for the supreme contest, war, and we expect to have much better soldiers out of young men who have had this training, that is, the previous conditioning and training of naked bodies, which makes them not only stronger and healthier, more agile and fit, but also causes them to outweigh their opponents.

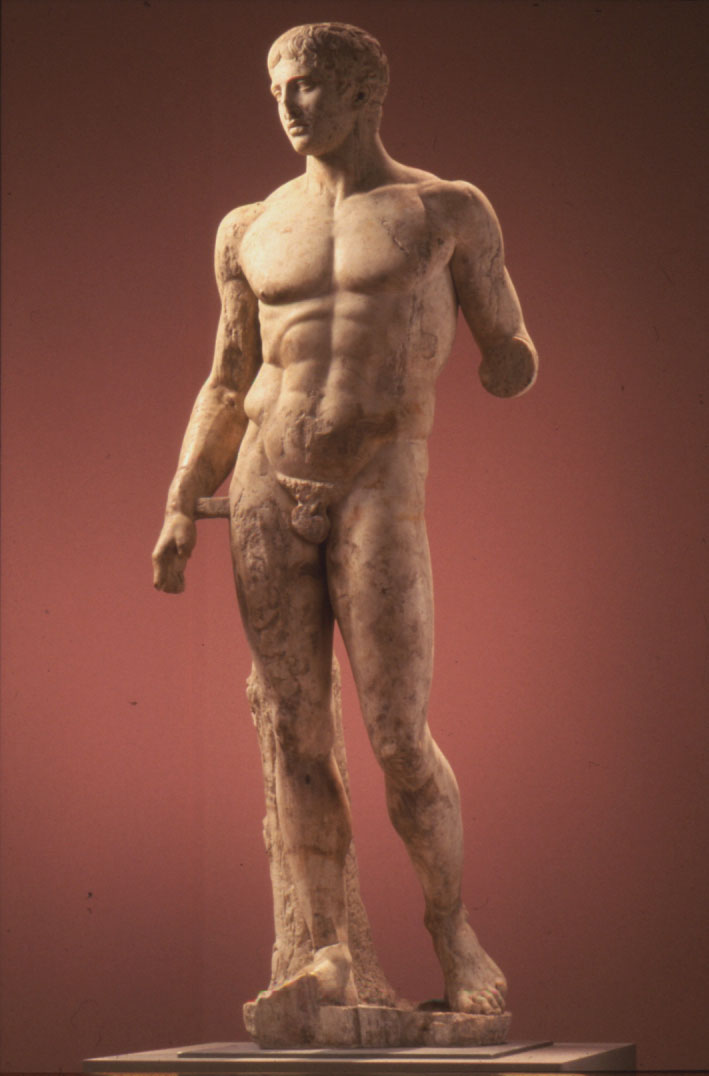

You can see, I should think, the results of this, what they are like when armed, or even without weapons how they would strike terror in their enemies. Our troops are not fat, pale, and useless nor are they white and scrawny ... enervated by lying in the shade, simultaneously shivering and streaming with rivers of sweat, gasping beneath their helmets, particularly if the sun, as now, is burning with noontime heat. What use could people be who get thirsty and cannot endure dust; soldiers who panic if they see blood, who die of terror before they come close enough to throw their spears or to close with the enemy? But our troops have skin of high color, darkened by the sun, and faces like real men; they display great vigor, fire, and virility. They glow with good health, and are neither shriveled skeletons nor excessively heavy, but they have been carved to perfect symmetry; they have used up and sweated off useless and excess flesh, and that which is left is strong, supple, and free, and they vigorously keep this healthy condition. For just as the winnowers do with wheat, so our athletes do with their bodies, removing the chaff and the husks and leaving the grain in a clean pile.

Through training like this a man can't avoid being healthy and can stand up indefinitely under stress. Such a man would sweat only after some time, and he would seldom be seen to be ill. Suppose someone were to take two torches and throw one into the grain and the other into the straw and chaff -- you see, I am returning to the figure of the winnower. The straw, I think, would burst into flames much more quickly, but the grain would burn slowly with no large flames blazing up nor would it burn all at once, but it would smoulder slowly and eventually it too would be burned.

Neither disease nor fatigue could easily attack and overcome such a body or easily defeat it. For it has good inner resources which defend it against attacks from outside, so as not to let them in, neither does it admit the sun or the cold to its hurt. To avoid yielding to hardships, great vigor springs up within, something prepared long in advance and held in reserve for time of need. This vigor fills up at once and waters the body in a crisis and makes it strong for a long time. For the previous training in bearing strain and hardship does not weaken their strength but increases it, and when you fan it the fire burns stronger.

We train them to run, getting them to endure long distances as well as

speeding them up for swiftness in the sprints. This running is not done on a firm springy surface but in deep sand, where it is not easy to place one's foot forcefully and not to push off from it, since the foot slips against the yielding sand. We train them to jump over ditches, if they have to, or any other obstacles, and in addition we train them to do this even when they carry lead weights as large as they can hold. They also compete in the javelin throw for distance. In the gymnasium you also saw another athletic implement, bronze, circular, like a tiny shield with no bar or straps. You handled it as it lay there and expressed the view that it was heavy and hard to hold on to because it was so smooth. Well, they throw this up in the air both high and out, competing to see who can throw the longest and pass beyond the others. This exercise strengthens the shoulders and builds up the arms and legs.

As for this mud and dust, which originally seemed so amusing to you, my

friend, listen while I tell you why it is used. First, their fall will not be on unyielding dirt but they will fall safely on soft ground. Next, their slipperiness has to be greater when they sweat in the mud. You likened them to eels, but the facts are neither useless nor humorous: it adds not a little to strength of the sinews when they are forced to hold firmly to people in this condition when they are trying to slip away. Do not think it is easy to pick up a sweaty man in the mud, covered with oil and trying to get out of your arms. All these skills, as I said earlier, are useful in combat, if it were necessary to pick up a wounded friend and carry him easily to safety or to seize an enemy and bring him back in your arms. And for this reason we train them beyond what is necessary, so that when they have practiced hard tasks they may do smaller ones with much greater facility.

We believe the dust is used for the opposite reason than the oil is, that is, so that a competitor may not slip out of his opponent's grasp. For after they have been trained in the mud to hold fast to something which is escaping from them because of its slipperiness, they then practice escaping out of the arms of their opponent, no matter how impossibly firm they may be held. Furthermore when this dust is used liberally it checks the perspiration and makes their strength last longer and furnishes protection against harm from drafts which otherwise attack the body when the pores are open. Besides, the dust rubs off the accumulation of dirt and makes the skin gleam.

I should dearly like to stand one of those white-skinned fellows who live in the shade beside one of our boys who work out in the Lykeion, and after I had washed off the dust and the mud, ask you which one you would like to resemble. For I know that you would choose at first glance, without hesitation, even without putting either through any tests, the one which is solid and hard rather than soft, weak, and pale, because what little blood he has has been withdrawn into the interior of his body.

[Anacharsis then ridicules the idea that athletic training could be useful in war. Why not save your strength, he asks. Solon explains that strength cannot be saved like a bottle of wine; it must be constantly used.]

Anacharsis: I just don't understand what you said, Solon. It is too intellectual for me and requires a sharp mind and keen insight. But above all, tell me this, why, in the Olympic Games and at Isthmia and Delphi and elsewhere, where so many competitors, you say, assemble to see these young men compete, you never have a contest with weapons but you bring them before the spectators all naked and exhibit them getting kicked and punched, and then, if they have won, give them berries and wild olives? It would be worth knowing why you do this.

Solon: My dear Anacharsis, we do this because we think that their enthusiasm for athletics will increase if they see that those who excel at them are honored and are presented to crowds of Greeks by heralds. Because they are to appear stripped before so many people, they try to get into good condition, so that when they are naked they will not be ashamed, and each one works to make himself capable of winning. As for the prizes, as I said earlier, they are not insignificant: to be praised by the spectators, to be a recognized celebrity, and to be pointed out as the best of one's group. As a result of these prizes, many of the spectators who are of the right age for competition go away completely in love with courage and struggle. If someone should remove love of glory from our lives, what good would we ever achieve, Anacharsis, or who would strive to accomplish some shining deed? But now it is possible for you to imagine from these games what sort of men these would be under arms, fighting for fatherland and children and wives and temples, when they show so much desire for victory in competing for laurel berries and wild olives.

Furthermore, how would you feel if you should observe fights between

quails and between roosters here among us, and see the great interest

which is shown in them? Wouldn't you laugh, particularly if you should learn that we do this in accordance with our laws and all men of military age are instructed to be present and to see these birds fight until they are exhausted? But it is no laughing matter, for eagerness for danger creeps insensibly into their souls so that they try not to seem less courageous and bold than the roosters nor to give in too soon because of injury or fatigue or any other distress.

As for trying them in armed combat and seeing them receive wounds --

never! It is brutal and dreadfully wrong, and in addition it is economically unfeasible to destroy the bravest, whom we could better use against our enemies.

Since you tell me, Anacharsis, that you expect to travel to the rest of

Greece, if you get to Sparta, remember not to laugh at them nor think that they have no purpose when they compete in a theater, rushing together and striking each other, fighting over a ball, or when they go into a place surrounded by water [known as Plantanistas, or Plane-Tree Grove], choose up sides, and fight as if in actual war, although as naked as we Athenians are, until one team drives the other out of the enclosure into the water, the Sons of Herakles beating the Sons of Lykurgos or vice versa; after this contest there is peace and no one would strike another. In particular, do not laugh if you see them being whipped at the altar, streaming with blood, with mothers and fathers standing by, not at all bothered by what is happening but on the contrary threatening them if they do not hold up under the blows, urging them to bear up under the pain as long as possible, and to be strong under this hideous treatment. To tell the truth, many have died in these contests, not thinking it manly to yield before the eyes of their friends and relatives while they are still alive, no, not even to flinch. You will see honors paid to statues of people like this erected at public expense by the state of Sparta.

~ translated by Sweet.

Please click here to Return to the main article.

Indeed, to some historians -- notably the Swiss Jakob Burkhardt (1818 - 1897) -- this "agonal drive" was the key to understanding an entire mentality. In his unequivocal words, "All Greek life was animated by this principle."

But using such relationships between men as a font of military excellence is a transparent borrowing from Sparta, where such relationships were institutionalized, played a large role in the training of boys, and were thought to contribute to bravery in combat. At Sparta lover and beloved stood beside each other in the hoplite line; before battle the Spartans sacrificed to Eros, to love.

In Athens the legacy of Spartan success was experts in hoplite technique for hire; in Thebes, it was the trained Sacred Band of three hundred lovers.

Spartans were open to the possibility, radical in the fifth century [BC], that physical courage itself was a consequence of training, rather than inborn.

"Man differs little from man by nature, but he is best who trains in the hardest school," Thucydides has a Spartan king say.

It is probably from the Spartans that intellectuals of the fifth and fourth centuries got the idea that courage was a function of experience or a mixture of training and inborn quality, an idea elaborated in philosophy into the doctrine that courage was a function of knowledge. . . .

I notice that as those who do not train the body cannot perform the functions proper to the body, so those who do not train the soul cannot perform the functions of the soul: for they cannot do what they ought to do nor avoid what they ought not to do.

Boxing was an invention of the Lakedaimonians [Spartans], which was adopted by the barbarian tribe of Berbrykians, and [the Spartan] Polydeukes was best at the sport; from these facts the poets made up their songs. The ancient Lakedaimonians boxed for the following reason: They had no helmets, nor did they think it was proper to their native land and Spartan ways to fight in helmets. They felt that a shield, properly used, could serve in the place of a helmet. Therefore they practiced boxing in order to know how to ward off blows to the face, and they hardened their faces in order to be able to endure the blows which landed.

When someone offered to give a Spartan king a cock who would die fighting, the king said, No, bring me the kind who will KILL fighting.

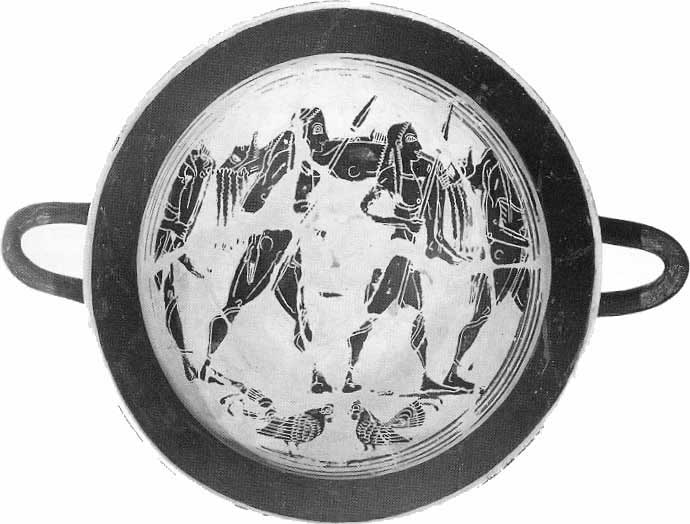

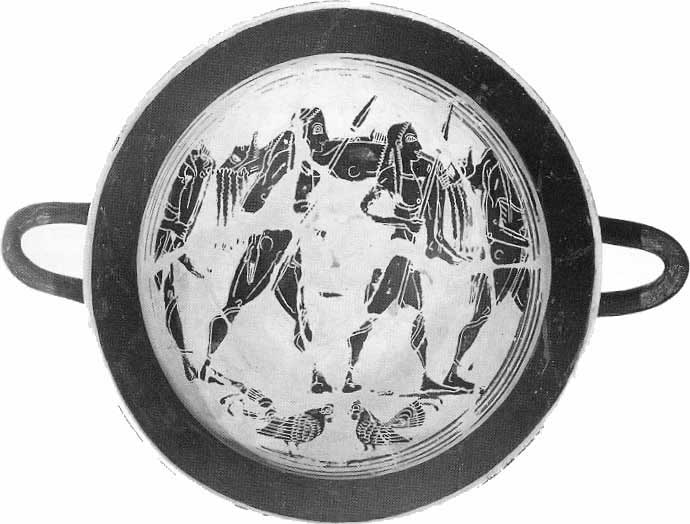

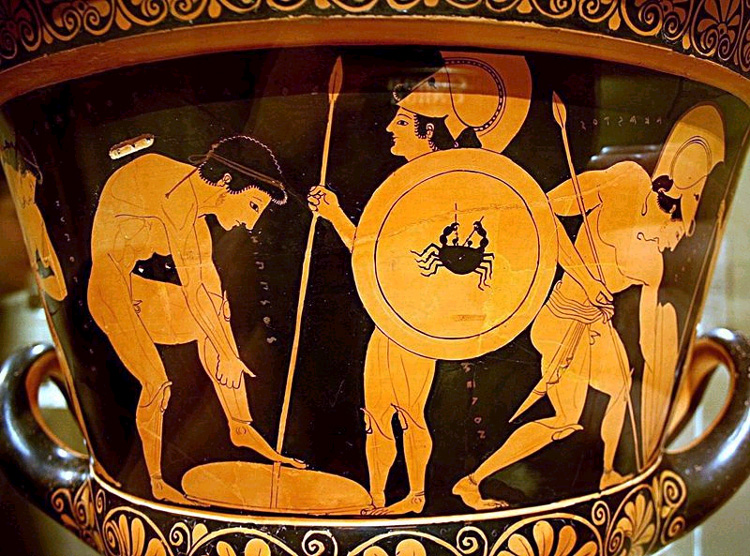

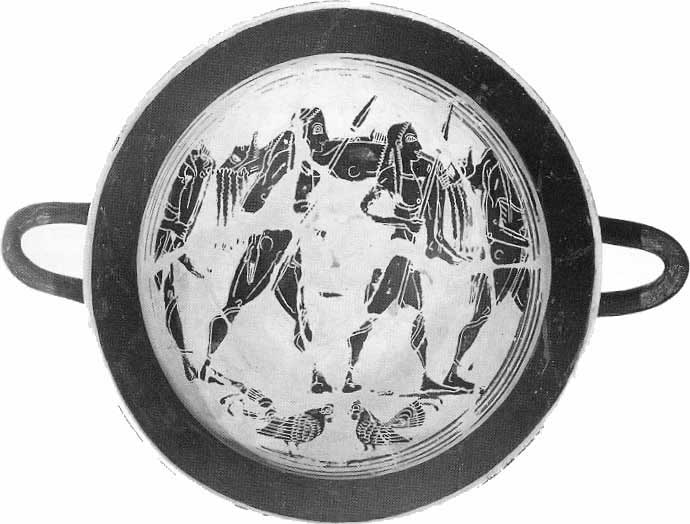

Spartan Kylix -- notice the Fighting Cocks at the bottom of the painting

[T]hey go into a place surrounded by water [known as Plantanistas, or Plane-Tree Grove], choose up sides, and fight as if in actual war, although as naked as we Athenians are, until one team drives the other out of the enclosure into the water, the Sons of Herakles beating the Sons of Lykurgos or vice versa; after this contest there is peace and no one would strike another.

The father of Lysander, Aristocleitus, is said to have been of the lineage of the Heracleidae, though not of the royal family. But Lysander was reared in poverty, and showed himself as much as any boy conformable to the customs of his people; of a manly spirit, too, and superior to every pleasure, excepting only that which their good deeds bring to those who are successful and honored. To this pleasure alone it is no disgrace for the youth in Sparta to succumb.

[In their herds, the boys were] accustomed to live together and be brought up together, playing and learning as a group. The captaincy of the Herd was conferred upon the boy who displayed the soundest judgement and the best fighting spirit. The others kept their eyes on him, responded to his instructions, and endured their punishments from him, so that altogether this training served as practice in learning ready obedience. Moreover, as they exercised, boys were constantly watched by their elders, who were always spurring them on to fight and contend with one another; in this their chief object was to get to know each boy's character, in particular how bold he was, and how far he was likely to stand his ground in combat and struggle.

The life of a Spartan male was a life of discipline, self-denial, and simplicity. The Spartans viewed themselves as the true inheritors of the Greek tradition. They did not surround themselves with luxuries, expensive foods, or opportunities for [wasteful] leisure. And this, I think, is the key to understanding the Spartans. . . . [T]he life of the Spartans seemed to hark back to a more basic way of life. Discipline, simplicity, and self-denial always remained ideals in the Greek and Roman worlds; civilization was often seen as bringing disorder, ennervation, weakness, and a decline in moral values. The Spartan, however, could point to Spartan society and argue that moral values and human courage and strength was as great as it was before civilization. Spartan society, then, exercised a profound pull on the surrounding city-states who admired the simplicity, discipline, and order of Spartan life.

The rest of the Greeks saw with astonishment and admiration how every institution in Sparta served the same purpose -- to make Spartan citizens the best soldiers in the world. They understood very well that this was not done by incessant drilling and manoeuvring, but by moulding the character from earliest childhood. This education was not only military. It was political and moral in the broadest sense ...

Spartiates' training extended into adulthood, for no one was permitted to live as he pleased. Instead, just as in a [miltary] camp [while at war], so in the city they followed a prescribed lifestyle and devoted themselves to communal concerns. They viewed themselves absolutely as part of their country, rather than as individuals, and so unless assigned a particular job they would always be observing the boys [in the agogé] and giving them some useful piece of instruction, or learning themselves from the elders. Abundant leisure was unquestionably among the wonderful benefits which Lycurgus had conferred upon his fellow citizens. While he totally banned their involvement in any manual craft, there was equally no need for them to amass wealth (with all the work and concentration which that entails), since riches were emphatically neither envied nor esteemed. ... As might be expected, legal disputes disappeared along with coinage, since there was no longer greed or want among them, but instead equal enjoyment of plenty, and the sense of ease which comes from simple living. Except when they went on campaign, all their time was taken up by choral dances, festivals, feasts, hunting expeditions, physical exercise and conversation.

equal enjoyment of plenty, and the sense of ease which comes from simple living. Except when they went on campaign, all their time was taken up by choral dances, festivals, feasts, hunting expeditions, physical exercise and conversation.

who reject anal penetration, promiscuity, and effeminacy

among men who have sex with men

| Heroes Site Guide | Toward a New Concept of M2M | What Sex Is |In Search of an Heroic Friend | Masculinity and Spirit |

| Jocks and Cocks |

Gilgamesh | The Greeks | Hoplites! | The Warrior Bond | Nude Combat | Phallic, Masculine, Heroic | Reading |

| Heroic Homosex Home | Cockrub Warriors Home | Heroes Home | Story of Bill and Brett Home | Frot Club Home |

| Definitions | FAQs | Join Us | Contact Us | Tell Your Story |