12345678910

12345678910

The Strife of Valour: Ares is Lord; Greece has no fear of gold; Austerity and Equality at Sparta

1-3-09

Hi guys.

This post looks at the current economic crisis and what Sparta can tell us about surviving such a crisis.

Like the crisis, the post is long.

But it's in sections.

And to make it easier for folks who want to read one section at a time, there's this Table of Contents:

I hope you'll take the time to read the entire post.

Like Excellence, Honor, and the Molding of Men, this is a post I'll be referring back to, because it introduces the core Warrior concepts of Austerity and Equality, explains how they functioned at Sparta, and looks at how they can enrich our own lives.

Bill

τhis post, which addresses cultural issues brought forward by the credit crunch and the subsequent economic crisis, was inspired by Warrior Brian Hulme, who sent me the following email:

As for the credit crunch, well it will not affect me, because 1) I can not lose my job, as I am already unemployed and on State (Government) benefit. 2) My reason for donating, if you remember, was that the church I was in and at that time leaving was treating me in an un Christian way and not supporting me but I got the support I needed from the Man2Man Alliance and you. The tithe that I paid to them at that time was 10% of my income and I considered it a sacred trust and not for my use. When I left the Church this money was left with "nothing to do" or I could every 4 weeks send it to you as a "tithe" and as much of a sacred trust. I now think of Patrick as my Pastor, you as my Elder and Robert and Naked Wrestler and the many other contributors to the Alliance web site Warrior Brothers in this my new church as we share a new type of love and belief that involves total Manly love, physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual.

The credit crunch can crunch away, but it will NOT crunch my Manhood my Masculinity or my Warriorhood and it will not stop me sending my donations to the Alliance, because I hunger for the establishment of (through setting up of Regional Chapters by Warrior couples) a Warrior Community and that can only happen if we are committed to the cause of Warriorhood in every way we can be, and this includes sending as much in donations as often as we can.

Brian

In his email, Brian is, implicitly I feel, contrasting the values of those who've created the credit crunch -- and of those who fear the credit crunch -- with his own Warrior values of Manhood, Masculinity, and Warriorhood.

And he's being very clear:

A Warrior Community can only exist, he says, "if we are committed to the cause of Warriorhood in every way we can be."

He's right of course.

Which means he's hitting on crucial issues which you need to think about in terms of the choices you're making and will make in your lives.

Now, Brian lives in the UK, and so, while, as I told him, I'm sorry he's unemployed, he's at least getting benefits.

He also, as I understand this, gets medical care, regardless of whether he's currently employed.

Brian was ill recently and had to have an operation.

Because his society provides him with medical care, he didn't have to worry about the cost of that care.

So in the UK, even though the UK is a capitalist country, and even though it too has been hit hard by the credit crunch, there are COMMUNAL VALUES which help protect guys like Brian.

That's good.

And Brian shares in those communal values.

Because from his unemployment benefits, which from the point of view of an American, are meager --

he's tithing.

To which I say: Wow!

But I also recognize that his tithing is a reflection of his values, his communal values, which most of you reading this -- lack.

And in thinking about how to explain this to you, I came upon a phrase in Xenophon describing an aspect of Sparta and the Agogé.

That phrase is "The Strife of Valour."

If you can understand The Strife of Valour and the meaning of The Strife of Valour, then you can understand the values -- communal values -- which powered the Spartan experiment and made it so successful.

"Manhood, Masculinity, Warriorhood" says Brian.

Once again, he's right.

They're all part of The Strife of Valour.

And that's not all.

Because my reading of Xenophon led me to Plutarch's Life of Agesilaus, a Spartan king -- in which I came across this line of ancient Greek poetry:

That too is germane to our discussion.

So -- I've given this post a long title:

Ares is Lord

Greece has no fear of gold

Austerity and Equality at Sparta If you'll bear with me, you'll see how each element comes into play.

And how, in the place where Ares -- that is, the Warrior God -- is Lord; and where the Strife of Valour prevails; the people need have no fear of gold.

ωhat we've been seeing for months now, in the credit crunch and the ensuing collapse of the worldwide financial system, has been the strife of greed.

The strife of selfishness and self-interest.

Struggles among the greedy for an ever bigger piece of the pie are what has brought our world to this brink --

this brink of financial, social, and environmental disaster.

The strife of greed, then, is destructive.

It puts the individual first, no matter how destructive that individual's actions are to the common good.

The Strife of Valour is something entirely different.

As we'll see -- it destroys neither communities nor Men --

rather, it is the SALVATION of both.

The Way of the Warrior is the Way of Salvation;

and the Way of the Warrior is the Strife of Valour.

Again: the strife of greed is destructive.

The Strife of Valour is not, because, as we'll see, it's part of an effort to build both excellence -- Manhood -- and fellow-feeling among Warriors and thus strengthen and exalt their Warriorhood.

Warriorhood which exists in service to a community -- what we may think of as a Warriordom.

A Warrior Realm -- which is what Sparta was.

Now: In our time, the strife of greed is largely about the creation of needs and the creation of things to fulfill those needs.

Which begs the question:

What do human beings actually need?

Answer -- in my view:

Clean air, clean water, wholesome food, and exercise -- the last two in moderation -- and the communion and mutual aid of their fellows.

That's what they need.

They also need the freedom to be sexual -- within limits.

Sex must be genital and consensual.

That means they can't be allowed to rape, or buttfuck, or violate children.

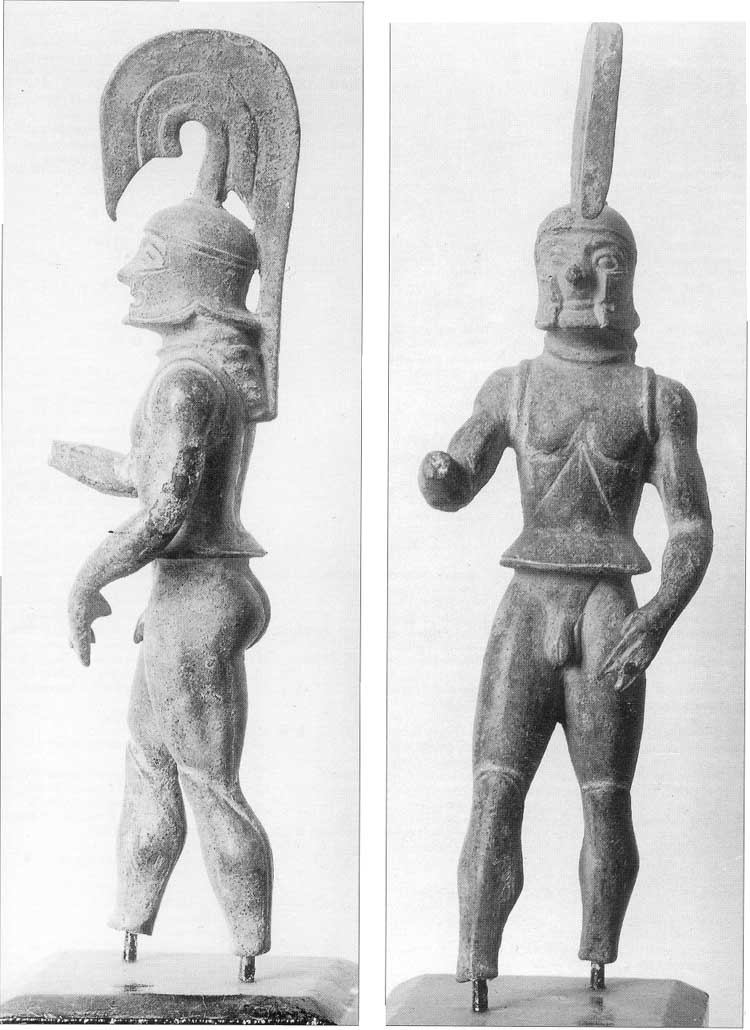

In addition, Men need to be able to Fight.

Women to bear children and nurture.

But, it should be noted, Spartan Women were encouraged to wrestle, to throw the javelin and discus;

while Spartan Men were expected to fully participate in the education, training, and moral acculturation of boys and young men.

At Sparta, both sexes experienced aggression -- and nurturance.

This then is what human beings need:

Clean air, clean water, wholesome food, exercise, and mutual aid;

sex, aggression, and children.

That's what human beings need.

Not SUVs and flat-screen TVs;

but the freedoms, rights, and obligations of their mutual humanity.

The Spartans had that.

We don't.

Yet, even in the midst of the credit crisis, our culture continues to emphasize and value material goods, often and predictably to the exclusion of our mutual humanity.

For example, I wrote that line about "SUVs and flat-screen TVs" back in October;

and in November, the New York Times ran this picture:

It's a photo of a man putting his newly-purchased flat-screen TV into his SUV -- life imitating, as it were, art.

He purchased the TV on "Black Friday" of this year, on the same day that a Wal-Mart employee was trampled to death by a mob of shoppers.

According to the International Herald Tribune:

"They were like a stampede," said Nassau Det. Lieutenant Michael Fleming. "Hundreds of people walked past him, over him or around him."

The reason the Wal-Mart worker was trampled to death is that the shoppers put their acquisition of things

ahead of their individual and mutual humanity.

It was more important to them to get a bargain -- a cheap object -- on the day after Thanksgiving, than it was to concern themselves with what had happened to a fellow human being.

That's a reflection of their values -- values which are cultural.

Cultural values.

The photos I just showed you appeared in the New York Times on Black Friday, and as such are a snapshot, a picture of the culture.

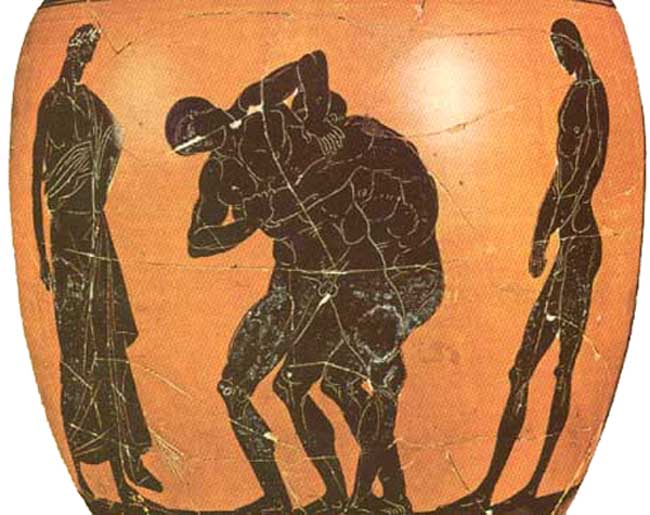

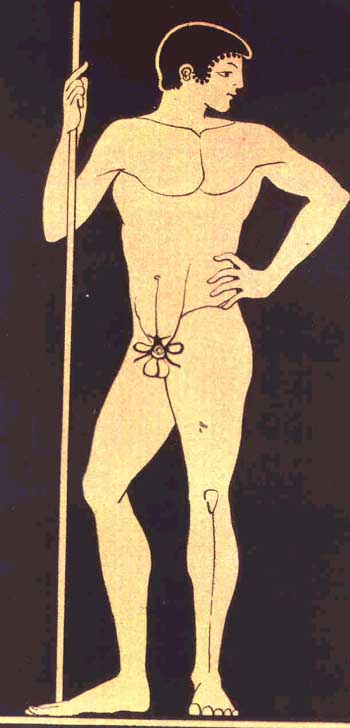

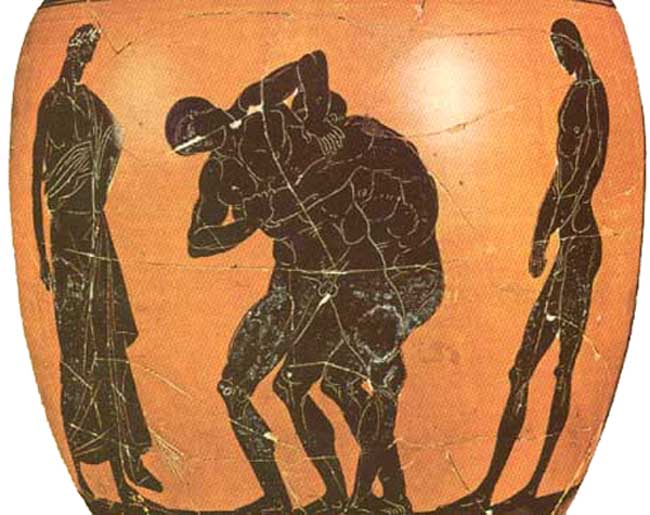

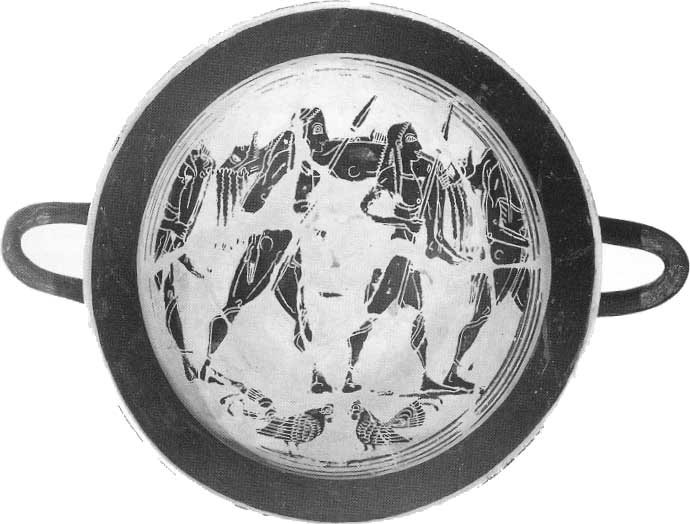

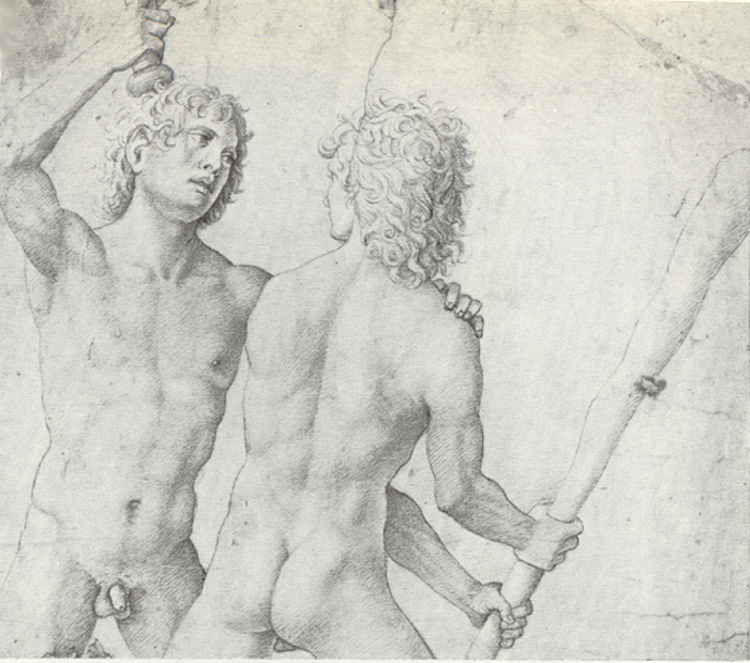

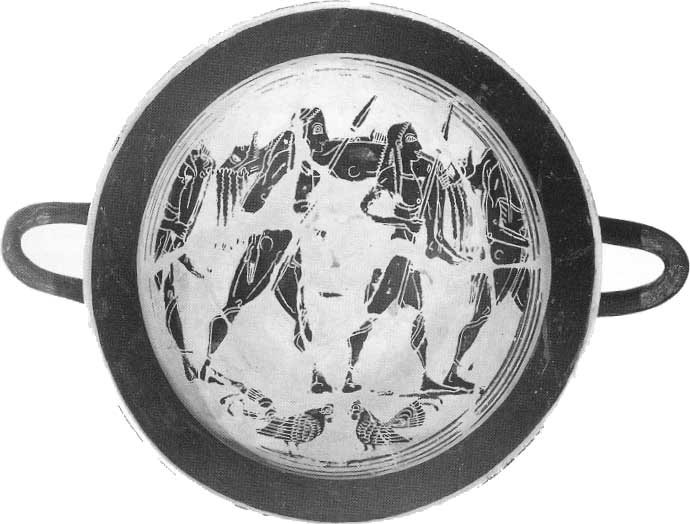

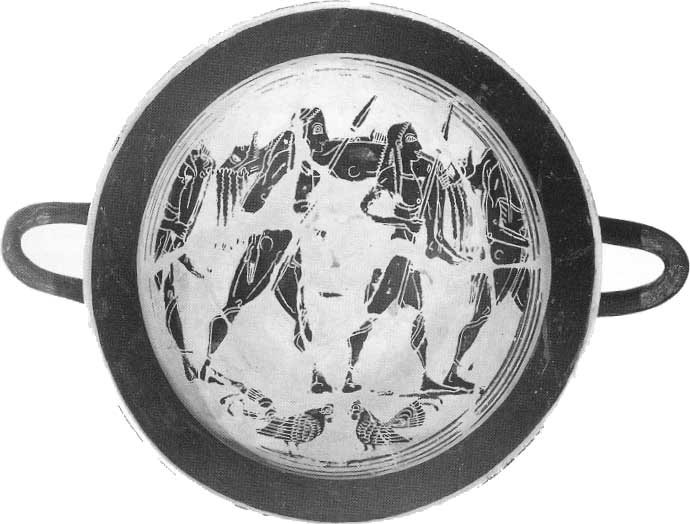

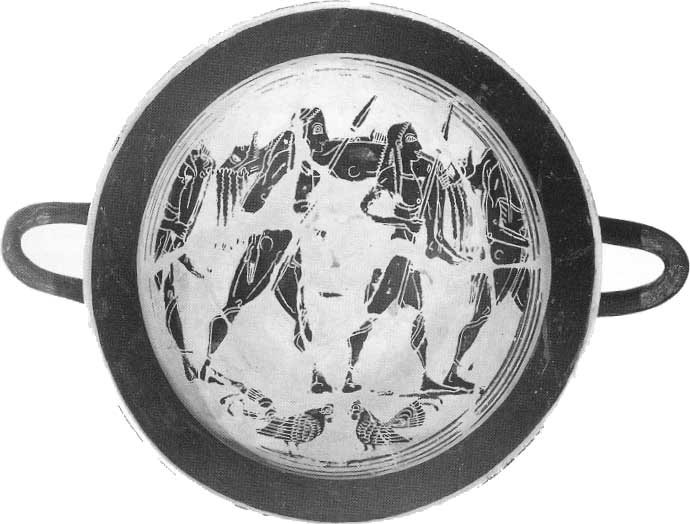

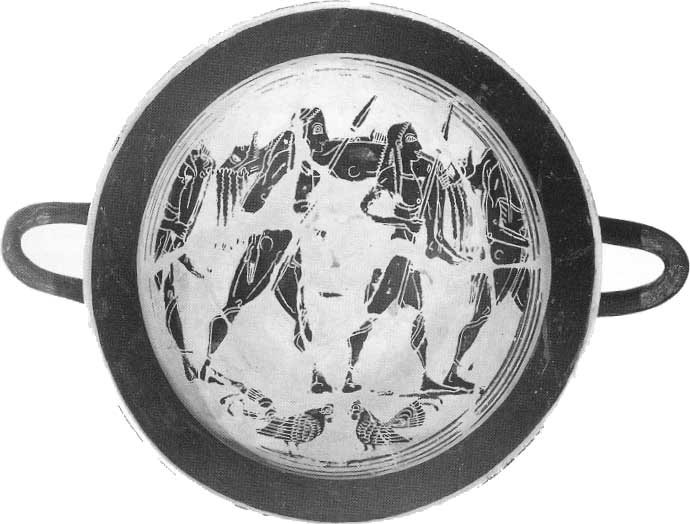

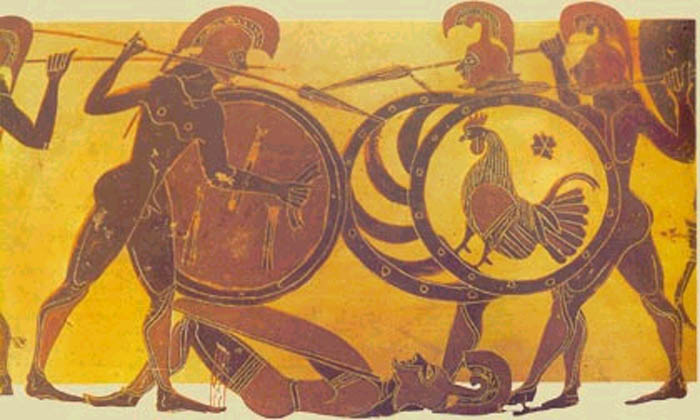

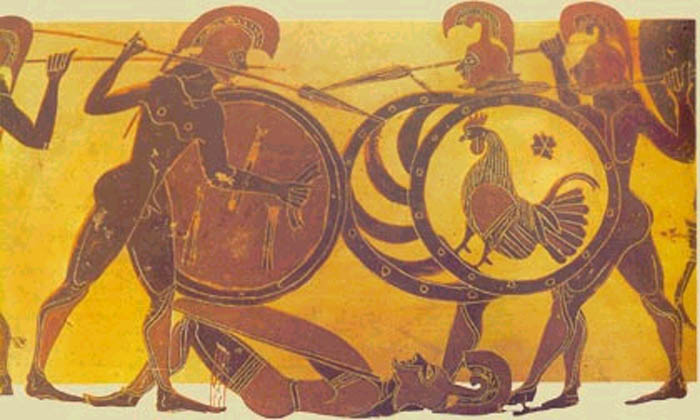

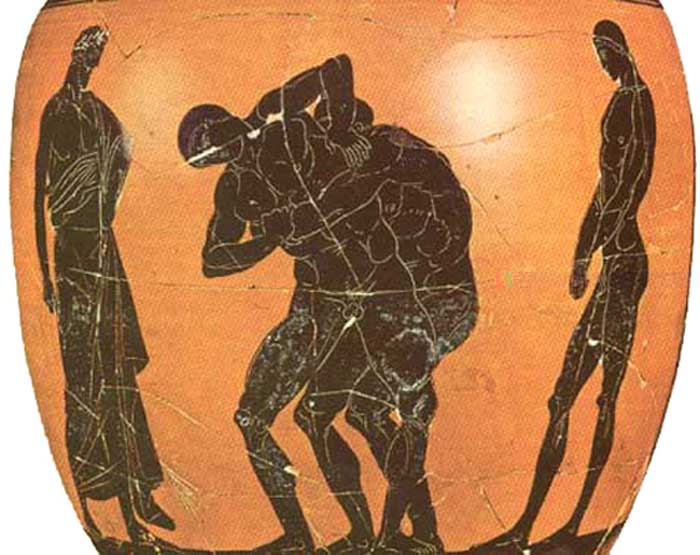

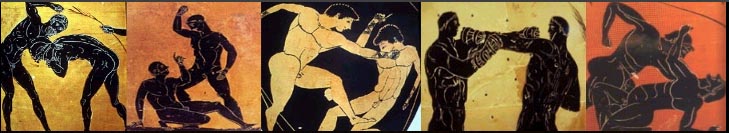

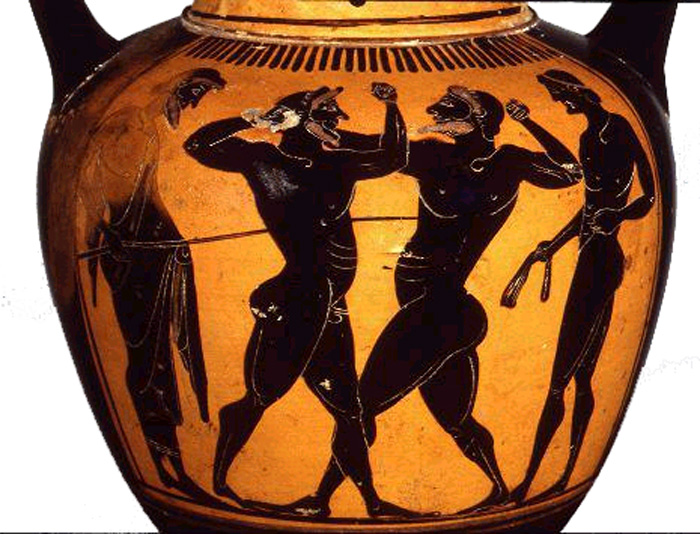

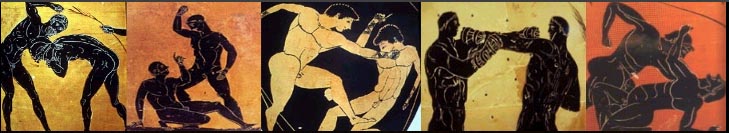

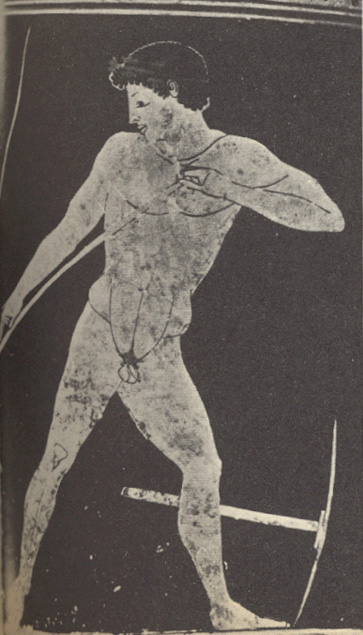

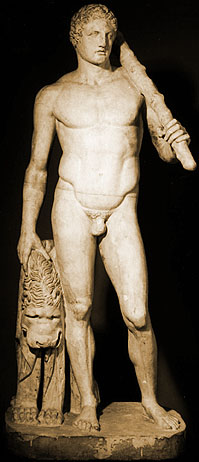

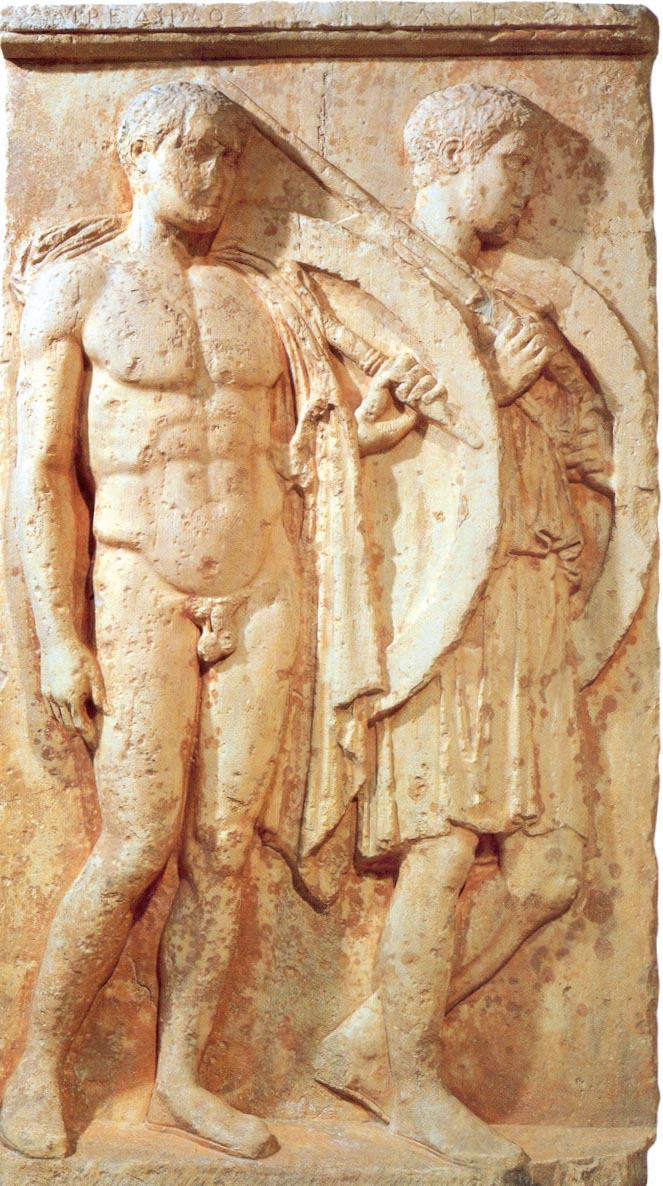

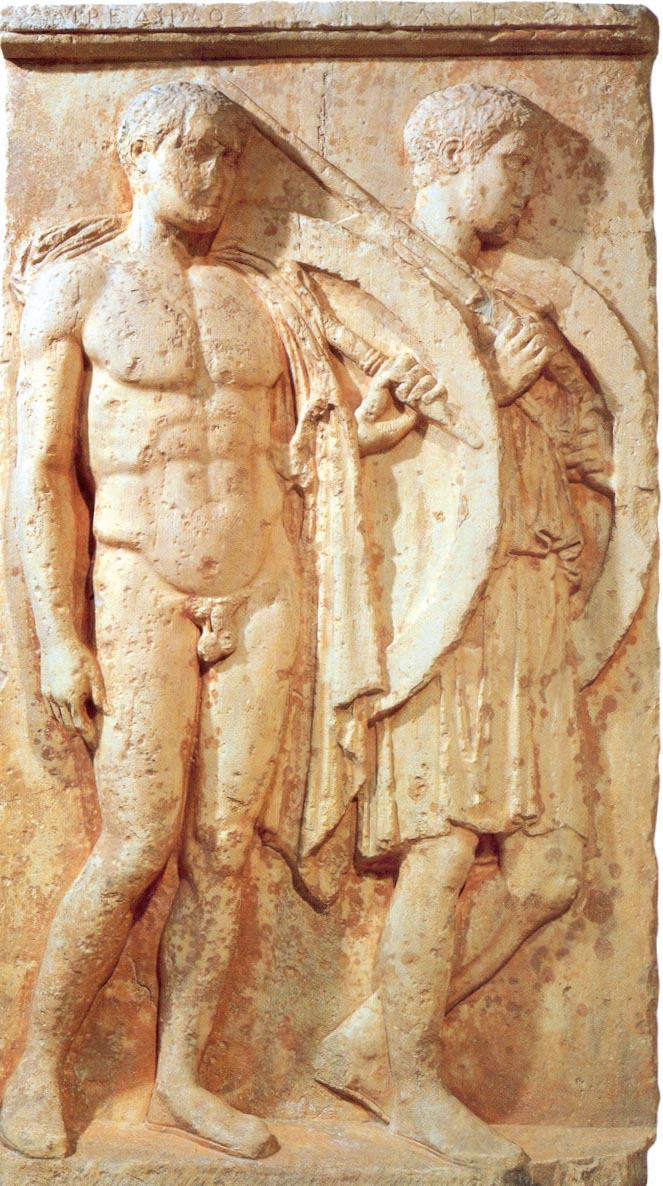

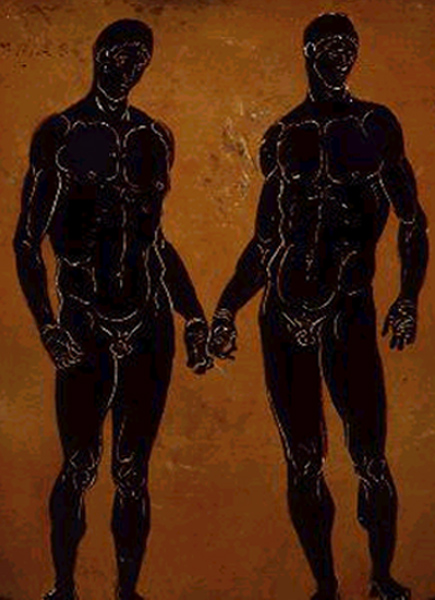

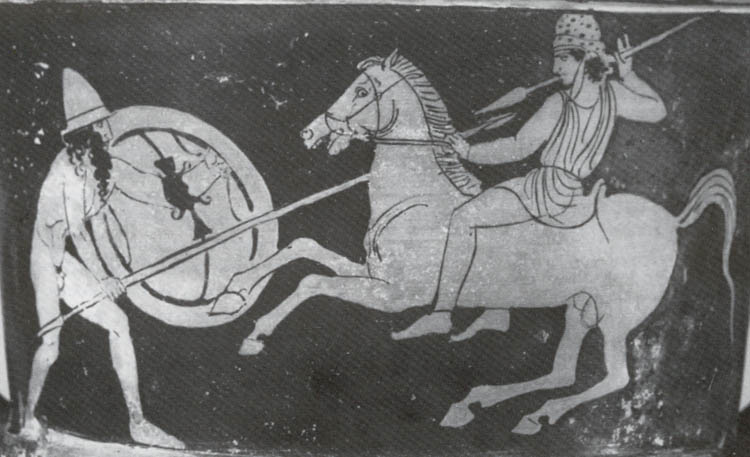

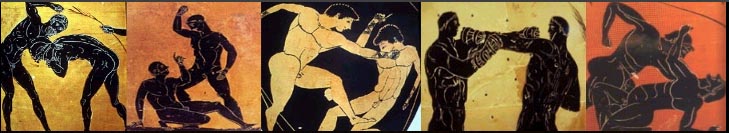

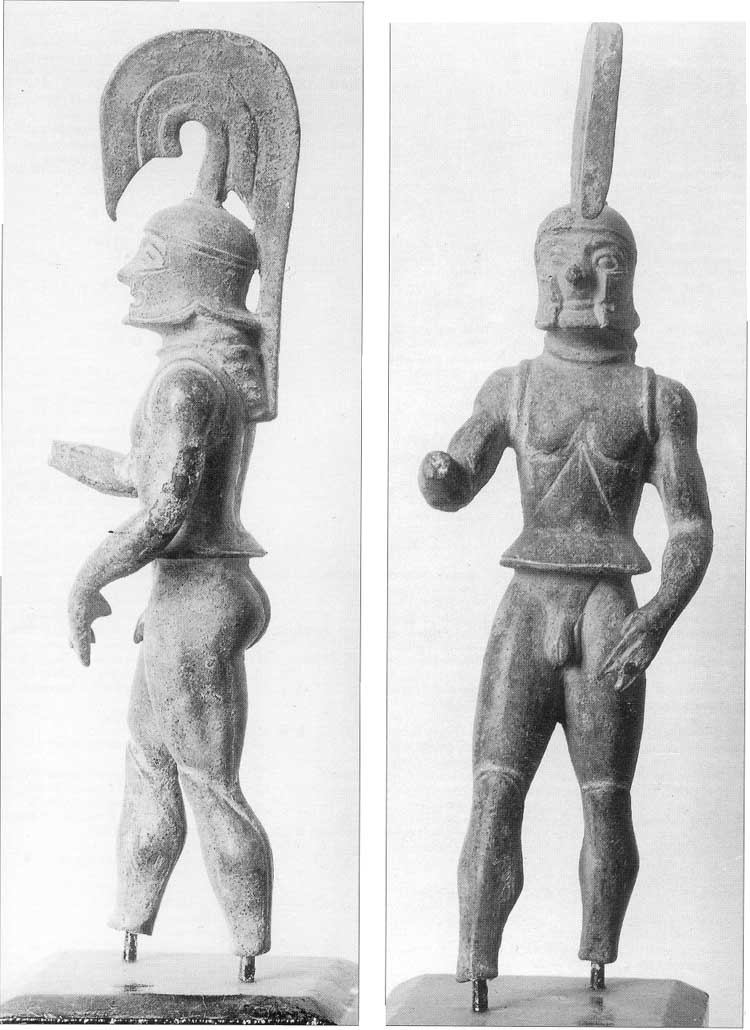

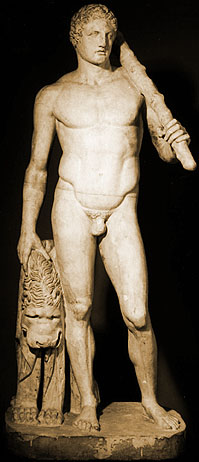

This Spartan drinking cup which I often show you is also a picture -- of its culture.

These guys have not been shopping.

They've been in battle.

True battle.

They've been Fighting.

True Fighting.

And they're happily carrying home the body of a fellow Warrior, one who Fell in the Fight.

He died honorably -- virtuously Xenophon would say.

His death was "kalos" -- noble and beautiful.

The Warriors carrying his body have lived honorably.

Their lives, says Xenophon, are also "kalos" -- noble and beautiful.

That's why they're happy.

Because they've behaved virtuously.

And in accord with the values of their community -- a Warrior community -- which puts human relationships -- including relationships between Warriors, such as those we examined in The Warrior Bond -- ahead of material possessions.

Their happiness depends not on things -- not on objects -- but on behavior, their own behavior, which they control;

and on the way that behavior shapes their relationships with other members of their community -- a Warrior community.

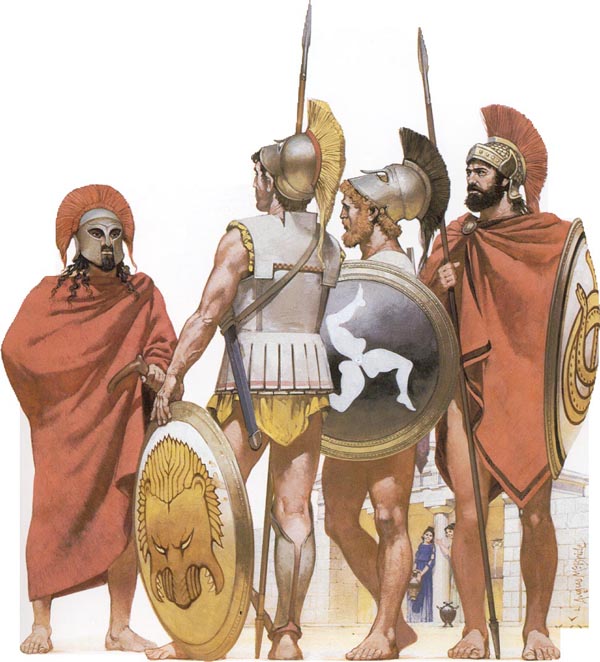

Materially, these people are poor.

The Men are nude and barefoot, their only adornment is their elaborately dressed hair, and as we'll soon see, they live austere lives in every other way as well.

But they're happy.

At Wal-Mart, shoppers stepped over, around, and upon the body of a fellow human being in order to obtain objects -- not food, not water -- but objects, things, stuff -- virtually all of it junk;

At Sparta, Warriors battled and fought -- they risked their lives -- to protect and bring home a wounded comrade or the body of a fallen comrade.

Big difference.

And that's because at Sparta, human relationships based on the core Warrior values of Nobility and Goodness -- aka areté -- were more important -- far more important -- than things.

And to ensure that Nobility and Goodness remained the core values at Sparta -- the Spartans instituted a regime of Austerity and Equality.

That's what they did.

They banned wealth.

And replaced it with areté -- excellence.

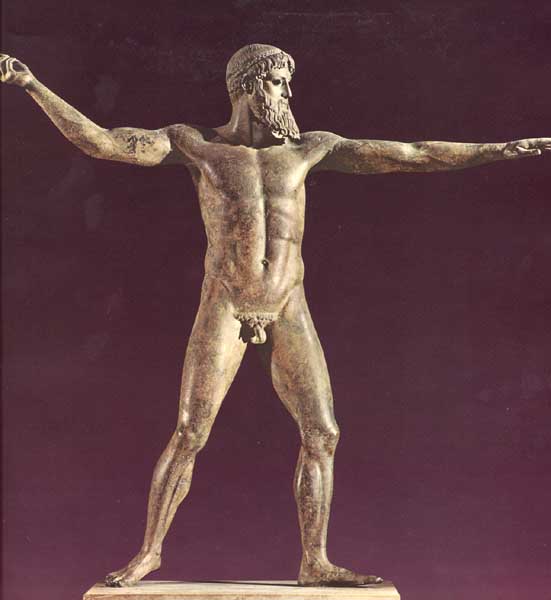

Areté -- as it arose from Ares.

Excellence -- as it arose, and by design, from Fighting, Combat, and Strife.

That's what they did.

And what they did worked.

Spectacularly well.

For centuries.

So -- it's like I said:

This is what human beings need:

Clean air, clean water, wholesome food, exercise, and mutual aid;

sex, aggression, and children.

That's what human beings need.

Not SUVs and flat-screen TVs;

but the freedoms, rights, and obligations of their mutual humanity.

The Spartans had that.

We don't.

And the reason we don't is rooted in our code of values -- our "value-system."

Let's start by talking about the credit crunch and values.

We've often heard, in the last few months, that Greed -- which is a value -- is what got us into this mess.

But, fact is, we've been told for years, at least in the US, that Greed is the best motivator in a society -- that Greed is what powers "Free Market Capitalism," and if we just cut Greed loose to do its thing, everyone will prosper.

Well, we did cut it loose.

And a few people prospered.

And the rest of us lost.

We've also been told, repeatedly over the last years, that "the Market is always right."

Well, the market, out where I live, was valuing houses at -- at least -- five, ten, or even more -- times their actual value.

In one case, I saw a "home" -- really just a shack, sitting on a scrubby lot with a chicken-wire fence -- listed for $215,000.

It's not worth more than $12 or $14,000.

And what happened?

Someone bought it for $215,000, he couldn't make the payments, he bailed out, the bank has it, and last I heard the bank was demanding $130,000 for it.

Dream on.

So -- the Markets aren't always right.

I know, I know -- we're told that the Markets are self-correcting.

See, that's like saying, psychiatry is always right, so psychiatry was right in the 1960s when it said that "homosexuality" was a "personality disorder" --

until it "self-corrected" in 1973 and decided that "homosexuality" wasn't a "personality disorder."

No.

Guys having sex with guys is not evidence of a "personality disorder."

It wasn't in the 1960s, and it isn't now.

Psychiatry was WRONG.

And the Markets were WRONG too.

As Alan Greenspan himself, admitted, more or less, at a Congressional hearing in October:

By EDMUND L. ANDREWS

Published: October 23, 2008

WASHINGTON - For years, a Congressional hearing with Alan Greenspan was a marquee event. Lawmakers doted on him as an economic sage. Markets jumped up or down depending on what he said. Politicians in both parties wanted the maestro on their side.

But on Thursday, almost three years after stepping down as chairman of the Federal Reserve, a humbled Mr. Greenspan admitted that he had put too much faith in the self-correcting power of free markets and had failed to anticipate the self-destructive power of wanton mortgage lending.

"Those of us who have looked to the self-interest of lending institutions to protect shareholders' equity, myself included, are in a state of shocked disbelief," he told the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform.

...

"You had the authority to prevent irresponsible lending practices that led to the subprime mortgage crisis. You were advised to do so by many others," said Representative Henry A. Waxman of California, chairman of the committee. "Do you feel that your ideology pushed you to make decisions that you wish you had not made?"

Mr. Greenspan conceded: "Yes, I've found a flaw. I don't know how significant or permanent it is. But I've been very distressed by that fact."

[emphasis mine]

Mr Greenspan's ideology -- his belief in greed and the markets -- was, he now admits, flawed.

Which means that the two values on which our society runs -- Greed and the Marketplace -- are not reliable.

They just aren't.

What's more, Mr Greenspan's ideology went beyond a simple belief in greed and the markets -- towards something which we can call "dollar-worship."

And I do mean dollar-*worship*.

Because it turns out that Greenspan, who was for so many years head of the Federal Reserve and whose pronouncements not just on the economy but just about anything were given great weight by the Congress, by most of the rest of government, and certainly by American society, is, according to the International Herald Tribune, a follower of Ayn Rand:

Well, that's one way of putting it.

Rand, a White Russian refugee who hated communism and collectivism, put Greed at the center of her philosophic system.

The Tribune refers to it as "the enlightened self-interest of individuals."

But in Rand's work, it comes across as individual Greed.

Indeed, at one point in her writing, Rand, who was an atheist, has a character say that the only symbol worth honoring is the dollar sign.

And Rand means it.

As a consequence, Greenspan was opposed to most government regulation of markets, including the derivatives market -- derivatives are complex financial instruments which are core to the present crisis; and, as I said, Greenspan strenuously and successfully opposed efforts, by the Congress and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, to regulate them, because, says the Tribune, he had "a resolute faith that those participating in financial markets would act responsibly."

Why anyone would believe that, given the history of the world and of bubbles in particular -- is beyond me.

But perhaps you would if you believed, as Rand and Greenspan did, that decisions based on Greed, and a society run on Greed, would be sound.

Look: I have said that core to my work is a simple idea:

That you must question the dominant paradigms -- the dominant social models -- of your era.

Whether they be "heterosexuality" or analism.

Now -- one of the dominant paradigms of our present era is that Greed is good and that the Markets are always right.

But use your eyes.

The Markets were NOT right.

And if the markets were not right, then the theory is wrong.

Some of you no doubt believe that the crisis is due to "bad actors."

No no no no no.

It's the theory behind the actors which is the problem.

It's like saying that psychoanalysis couldn't rid me of my Love of Men and Masculinity -- because my psychiatrist was a bad psychiatrist.

Or that I was a bad patient.

No.

It was that the theory behind the pyschoanalysis was wrong.

Because the Love of Man for Man is normal and natural.

Not diseased.

Same with analism.

It's like saying, which many of the buttboys in the person of the AIDS Service Organizations do, that anal would be fine if everyone used condoms.

No.

Anal is an inherently UNnatural act.

It's inherently dangerous.

And if you have to wear a condom to do something -- chances are you shouldn't be doing it.

So -- the theory of Markets and Greed -- is wrong.

And when you look at an event like the present credit crisis, you need to look at the theory behind the event.

Because there's always a theory -- a paradigm or model -- which is guiding the actors.

Analism is one such theory.

Genderism is another.

The medical model of homosexuality was another, which was seemingly done in, but which has survived as sexual orientation.

And the theory of Markets and the salutary effects of Greed -- is another.

So: dollar-worship, greed, the marketplace -- major players in the American value system -- are in fact phoney theologies based on faulty and failed theories.

Which means we face a choice:

We can continue down the disastrous road of dollar worship and greed;

or we can rejoin the human race and behave once again like human beings.

And that means first and foremost looking at other values.

What other values are there?

Communal values.

Including what's called "reciprocal altruism" -- I'll help you if I have a reasonable expectation that at some point in the future you'll help me -- and which we in the Alliance, along with every other Warrior Culture, elevate to Warrior Altruism.

And that's what's powered most societies throughout history -- altruism, reciprocal or otherwise, and mutual aid.

Not greed.

Feminist author Margaret Atwood, with whom I don't often agree, had this to say about reciprocal altruism in an op-ed in the NY Times:

We are social creatures who must interact for mutual benefit, and - the negative version - who harbor grudges when we feel we've been treated unfairly. Without a sense of fairness and also a level of trust, without a system of reciprocal altruism and tit-for-tat - one good turn deserves another, and so does one bad turn - no one would ever lend anything, as there would be no expectation of being paid back. And people would lie, cheat and steal with abandon, as there would be no punishments for such behavior.

Children begin saying, "That's not fair!" long before they start figuring out money; they exchange favors, toys and punches early in life, setting their own exchange rates. Almost every human interaction involves debts incurred - debts that are either paid, in which case balance is restored, or else not, in which case people feel angry. A simple example: You're in your car, and you let someone else go ahead of you, and the driver doesn't nod, wave or honk. How do you feel?

...

Atwood is correct about how reciprocal altruism functions.

And she ends her piece by saying that people need to "recognize that there is such a thing as the common good."

That's something which previous societies took for granted.

Including the Greeks, who, for all their competitiveness and individualism, recognized that communal values -- the common good -- mattered.

Indeed, that's one of the reasons they so admired and respected Sparta.

Now, I'm going to talk about the Greeks, and Sparta, because I think doing so is very helpful for you guys.

But let me be clear.

It's not just the Greeks.

The ancient Hebrews, for example, didn't think that greed and the marketplace were what should govern their society.

Nor did Jesus.

He took a very dim view of greed, and the marketplace, and scourged the moneychangers out of the temple.

That said, let's talk about ancient Greece -- and Sparta in particular.

In Excellence, Honor, and the Molding of Men -- and once again, if you haven't read that article, it's important that you do -- we discussed how "excellence" was the primary value for the Greeks.

What was "excellence" in ancient Greece about?

At first -- in Homer -- "excellence" denoted valour in battle and a sort of courtly morality.

Valour in battle.

Fighting Spirit.

Indeed, in Excellence, Honor, and the Molding of Men, we saw that the Greek word for excellence, areté, was derived from Ares, the Warrior God.

Ares -- Areté

Fighting Spirit -- the Spirit of Battle -- leads to Excellence.

Over time, areté also became identified with Nobility -- "kalos" -- and Goodness -- "agathos."

The Greeks took those two words -- "kalos" and "agathos" -- and combined them into one, by using an abbreviated form of their word for "and" -- kai:

Kalos kai agathos =

Kalokagathia -- Nobility and Goodness.

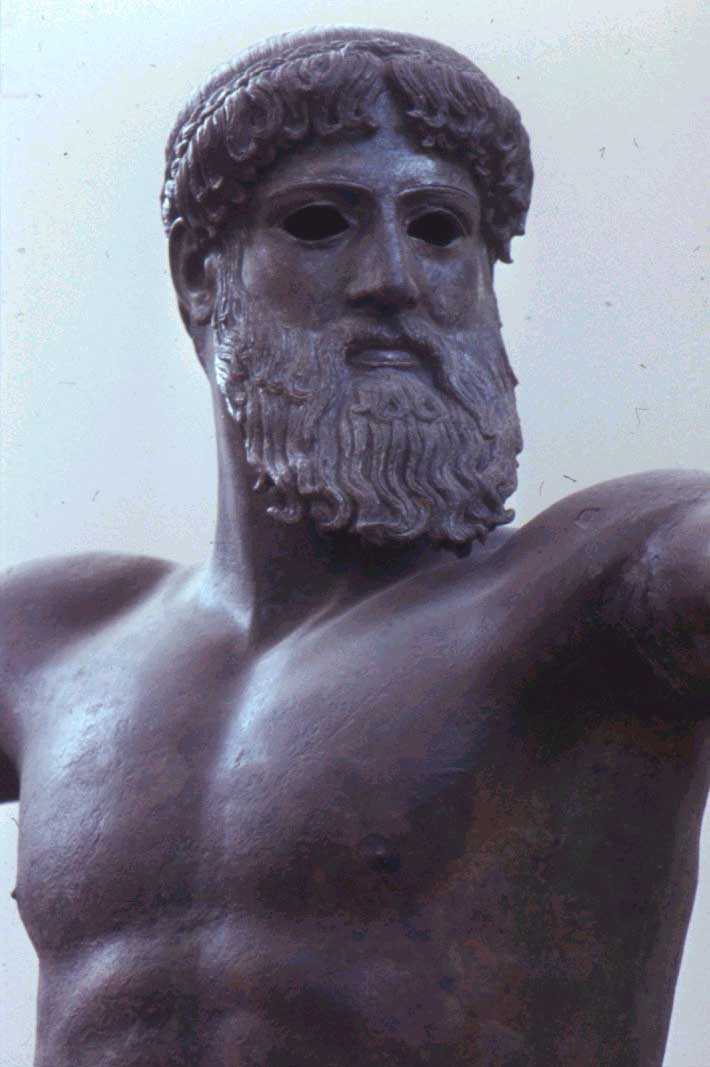

Noble also meant Beautiful.

While Good was meant in the sense both of moral -- and of brave.

So that "kalokagathia" denoted a morally brave beauty.

Not just beauty, and not just brave, but morally brave.

Morality.

As Brian has said, values and morals and honour.

Which means that over time, excellence -- areté -- became identified with "moral beauty."

Which, in turn, was, basically, moral heroism -- that is, the sacrifice of self for another -- or for an ideal.

For example, to Aristotle, says classicist Werner Jaeger in his great work Paideia: The Ideals of Greek Culture,

So -- moral heroism -- the utmost sacrifice to an ideal -- is what defines moral beauty -- and excellence.

And it was excellence, the Greeks believed, which should be the prime motivator in society.

Not greed, and not the marketplace, but moral beauty -- excellence.

Now:

When I first introduced the Greek idea of "excellence," I put it in the context of the Latin trio -- Vir, Virilis, Virtus -- Man, Manliness, Virtue.

The Greeks do what is essentially the same thing.

As the standard Greek-English lexicon puts it:

"The first notion of goodness" is "that of manhood, bravery in war."

Manhood is good -- Manhood is goodness.

Fighting spirit is good -- Fighting spirit is goodness.

Bravery in war -- Valour -- is good; it too is goodness.

So that areté -- excellence -- also means "Manhood" -- "bravery in war" -- Valour -- and "Virtus" -- Virtue.

And that's quite plain in the Greek language.

Depending on the context, areté in the plural can mean "the virtues"; and in the singular "the virtuous."

Let's see how that played out in Sparta.

Spartan society, the Spartans believed, had been by-and-large shaped by a single, divinely-inspired individual named Lycurgus.

And as the Spartans told it, Lycurgus had found a society which was faltering -- which was falling apart, riven by class divisions.

Which were driven by greed.

His solution was to do away with greed, and replace it with areté -- excellence, valour, virtue.

Manhood.

Here's the great Greco-Roman historian Plutarch, writing ca 100 AD:

...there was a dreadful inequality in this regard, the city [Sparta] was heavily burdened with indigent and helpless people, and wealth was wholly concentrated in the hands of a few. Determined, therefore, to banish insolence and envy and crime and luxury, and those yet more deep-seated and afflictive diseases of the state, poverty and wealth, Lycurgus persuaded his fellow-citizens to make one parcel of all their territory and divide it up anew, and to live with one another on a basis of entire uniformity and equality in the means of subsistence, seeking preeminence through virtue [areté] alone, assured that there was no other difference or inequality between man and man than that which was established by blame for base actions and praise for good ones.

~ Life of Lycurgus, translated by Bernadotte Perrin

So: "there was a dreadful inequality ... the city was heavily burdened with indigent and helpless people, and wealth was wholly concentrated in the hands of a few."

Sound familiar?

Lycurgus was "[d]etermined, therefore, to banish insolence and envy and crime and luxury, and those yet more deep-seated and afflictive diseases of the state, poverty and wealth..."

With what did Lycurgus replace poverty and wealth as dividers and demarcators in his society?

Answer : "preeminence through virtue [areté] alone" expressed as "blame for base actions and praise for good ones."

And the word in Greek for "base" actions carries with it the connotation of "greedy" and "evil"; while the word for "good" actions is of course "kalos" -- noble and beautiful.

Basically then, the value system he established, and which was welcomed by the Spartans, was based not on poverty and wealth, which are after all functions of greed, but on areté -- excellence:

That's a value system which centers on areté aka moral beauty aka nobility and goodness aka moral heroism:

a man is praised for his good or noble actions -- which add to his areté -- and blamed for his base or ignoble actions -- which subtract from his areté.

Areté.

Moral heroism.

At Sparta, moral heroism is really Warrior Altruism.

The willingness of the Warrior to die for his fellow Warrior; and for their Warrior cause, which in this case is Sparta itself.

Sparta is a state, a city-state.

But it's also an idea and an ideal -- of Courage, and of Justice -- of the way Men -- and Women -- should live.

To some extent, the sense of the city-state as an ideal can be found throughout ancient Greece.

Jaeger thinks it's true everywhere.

But I think it's more clearly true of Sparta than of other places.

Here's Jaeger, speaking of the polis or city-state in general:

The enormous influence of the polis upon individual life was based on the fact that it was an ideal. The state was a spiritual entity, which assimilated all the loftiest aspects of human life and gave them out as its own gifts. Nowadays, we naturally think first of the state's claim to educate all its citizens during their youth. But public education was not advocated in Greece until it became a thesis of fourth century philosophy : Sparta, alone, at this early period, paid direct attention to the education of the young. Nevertheless, even outside Sparta, the early Greek city-state educated the members of its community, by utilizing the musical and athletic competitions which were held during the festivals of the gods. These competitions were the noblest reflection of the physical and spiritual culture of the age. Plato rightly calls gymnastics [nude athletics] and music 'the old-established culture'. That culture, which had originally been aristocratic, was fostered by the state through great and costly competitions; and these competitions did more than encourage musical taste and gymnastic skill. They really created the sense of community in the city. Once that sense has been established, it is easy to understand the Greek citizen's pride in membership of his state. To describe a Greek fully, not only his name and his father's are needed, but the name of his city.

So -- Jaeger mentions the Spartan system of state-education, and then says that although other states lacked such a system, they still fostered a sense of community.

And that no doubt is true.

But only Sparta had the Agogé.

And the effect of the Agogé had to be an exponential heightening and strengthening of the sense of community, of the webs of interrelationship that constituted the communal bonds.

That's obvious.

And it was something the other Greeks recognized.

As Jaeger himself says:

The rest of the Greeks saw with astonishment and admiration how every institution in Sparta served the same purpose -- to make Spartan citizens the best soldiers in the world. They understood very well that this was not done by incessant drilling and manoeuvring, but by moulding the character from earliest childhood. This education was not only military. It was political and moral in the broadest sense ...

So -- if we paraphrase Jaeger's description of the polis or city-state to make it specific to Sparta, we get an idea of how powerful the Spartan ideal actually was:

The enormous influence of Sparta upon individual life was based on the fact that it was an ideal. Sparta was a spiritual entity, which assimilated all the loftiest aspects of human life and gave them out as its own gifts. Nowadays, we naturally think first of the state's claim to educate all its citizens during their youth. But public education was not advocated in Greece until it became a thesis of fourth century philosophy : Sparta, alone, at this early period, paid direct attention to the education of the young.

And did so through its unique system of Warrior training and education known as the agogé, which moulded character from earliest childhood. This education was not only military. It was political and moral in the broadest sense.

In addition, Sparta educated the members of its community by utilizing musical and athletic competitions which were held during the festivals of the gods. These competitions were the noblest reflection of the physical and spiritual culture of the age. Plato rightly calls nude athletics and music 'the old-established culture'. That culture, which had originally been aristocratic, was fostered by Sparta through great competitions; and these competitions did more than encourage musical taste and athletic skill. Coupled with the agogé, they created the sense of community in the city.

And that's correct.

As we'll see in a forthcoming post, the most important Spartan festival was the Gymnopaidiai, or Festival of the Naked Youths, dedicated to Apollo, and consisting of both musical and athletic competitions.

And it was from those competitions that the Spartan law-giver, Lycurgus, conceived of another type of competition, which he called The Strife of Valour.

So -- Sparta was not merely a city-state.

It was "an ideal [and] a spiritual entity, which assimilated all the loftiest aspects of human life and gave them out as its own gifts."

Let's break that down:

Those "loftiest aspects of human life" included Courage and Heroism, as Jaeger himself says, speaking of Sparta and the great Spartan poet Tyrtaeus, who, he said, was "endeavouring to create a nation of heroes":

The early Greek city-state was small, but it had something truly heroic and truly human in its nature. Greece, and in fact all the ancient world, held the hero to be the highest type of humanity.

And one of those gifts was Equality -- which is a form of Justice.

And thus of Virtue.

Virtue.

We've seen that the word for excellence, areté, also means virtue.

And that the Greek for "the virtues" is "tas aretas."

There are, in Greek thought, four particularly important virtues, which are known as the Divine Virtues.

These Divine Virtues are contrasted by the Greeks with "human goods" -- things like health and strength and beauty -- and wealth.

Plato, writing ca 400 BC, says that if a person -- or a society -- seeks to acquire only the human goods, and ignores the Divine Virtues -- that person and/or society loses both.

Is he right about that?

In my experience, yes.

I've seen that repeatedly in the gay male community, and we're now seeing it in America and to some degree all over the world:

Too much emphasis on material goods and wealth, and too little on the divine virtues, leads to disaster.

Sparta sought to do away with wealth, and replace it with the four divine virtues.

Plato argues that at Sparta, only Courage mattered, but that's clearly not true.

The Spartans strove to produce a Just society -- "to live with one another on a basis of entire uniformity and equality in the means of subsistence";

they certainly valued Self-control;

of Wisdom -- by which the Greeks meant philosophical wisdom -- of Wisdom, said Plutarch,

while, and as we'll see in a forthcoming post, the Spartans were very Pious.

So the Spartans, as much as or more than the other Greeks, valued the four Divine Virtues -- all four.

While they despised greed and wealth.

As they'd been taught to do by Lycurgus:

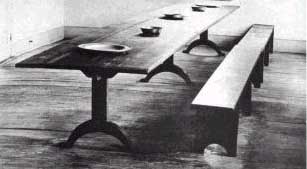

With the aim of stepping up the attack on luxury and removing the passion for wealth, [Lycurgus] introduced his third and finest reform, the establishment of common [all-male] messes. The intention was that they should assemble together and eat the same specified meat-sauces and cereals. This prevented them from spending the time at home, lying at table on expensive couches, being waited upon by confectioners and chefs, fattened up in the dark like gluttonous animals, and ruining themselves physically as well as morally, and by giving free rein to every craving and excess which demanded lengthy slumbers, warm baths, plenty of rest, and, in a sense, daily nursing.

This, then, was indeed a great achievement, yet, as Theophrastus says, it was an even greater one to have made wealth undesirable and to have produced 'non-wealth' by meals taken in common and by the frugality of the diet. When the rich man would go to the same meal as the poor one, he could have no use nor pleasure from lavish table settings, let alone view them or display them. Thus in Sparta alone of all the states under the sun was seen that proverbial blind Plutus [the god of wealth] lying inanimate and inert, as if in a picture. It was not even possible for the rich to dine at home first and then to proceed to their messes on a full stomach. Rather, the rest were on the look-out for whoever would not eat and drink along with them, and they would abuse him for having no self-discipline and for being too delicate to consume the common fare.

~ Plutarch, Life of Lycurgus, translated by Talbert

"This, then, was indeed a great achievement, yet, as Theophrastus says, it was an even greater one to have made wealth undesirable and to have produced 'non-wealth' by meals taken in common and by the frugality of the diet. ... Thus in Sparta alone of all the states under the sun was seen that proverbial blind Plutus [the god of wealth] lying inanimate and inert, as if in a picture."

So: Lycurgus "made wealth undesirable and produced 'non-wealth'"-- the Greek is a-plouton -- which implies a negation of wealth -- by the simple expedient of "meals taken in common and by the frugality of the diet."

In so doing, Lycurgus and the Spartans rendered the god of wealth "inanimate and inert" -- his life, which depended upon the worship of luxury and greed, sucked from him.

Like Plutarch says, that's quite an achievement.

The Spartans had replaced the individual value of wealth -- with the communal value of excellence.

So there are at least four elements to Sparta as "an ideal [and] a spiritual entity, which assimilated all the loftiest aspects of human life and gave them out as its own gifts":

(And it should be noted that, as we'll explore in a future post, the last three of these -- the communal messes, the Agogé, and religious-athletic festivals and competitions like the Gymnopaidiai and Hyakinthia, are intimately intertwined at Sparta with what Brian correctly calls "total Manly love, physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual" --

and indeed, all the aspects of what Jaeger calls "the Spartan cosmos" are intertwined and interconnected -- you can't separate the intense same-sex bonds from the Agogé or the Agogé from the communal male messes or either from the great religious-athletic-choral festivals or any of those from the emphasis on economic equality, austerity, constitutional government, and justice which are the hallmarks of Lycurgus' "Eu-nomia" -- his Good Rule.)

For now, however, and what we want to be clear about, is that the goal of all the elements in the Spartan system is to replace the individual value of wealth -- with the communal value of excellence.

As Xenophon, who lived around the same time as Plato, explains in his book The Constitution of the Lacedaemonians -- The Spartan Constitution.

IX. The following achievement of Lycurgus, again, deserves admiration. He caused his people to choose an honourable death [the Greek here is actually "kalon thanaton" which means a noble and beautiful death] in preference to a disgraceful life. And, in fact, one would find on consideration that they actually lose a smaller proportion of their men than those who prefer to retire from the danger zone. To tell the truth, escape from premature death more generally goes with valour than with cowardice: for valour is actually easier and pleasanter and more resourceful and mightier. And obviously glory adheres to the side of valour, for all men want to ally themselves somehow with the brave.

However, it is proper not to pass over the means by which he contrived to bring about this result. Clearly, what he did was to ensure that the brave should have happiness, and the coward misery. For in other states when a man proves a coward, the only consequence is that he is called a coward. He goes to the same market as the brave man, sits beside him, attends the same gymnasium, if he chooses. But in Lacedaemon everyone would be ashamed to have a coward with him at the mess or to be matched with him in a wrestling bout. Often when sides are picked for a game of ball he is the odd man left out: in the chorus he is banished to the ignominious place; in the streets he is bound to make way; when he occupies a seat he must needs give it up, even to a junior; he must support his spinster relatives at home and must explain to them why they are old maids: he must make the best of a fireside without a wife, and yet pay forfeit for that: he may not stroll about with a cheerful countenance, nor behave as though he were a man of unsullied fame, or else he must submit to be beaten by his betters. Small wonder, I think, that where such a load of dishonour is laid on the coward, death seems preferable to a life so dishonoured, so ignominious.

X. The law by which Lycurgus encouraged the practice of virtue up to old age is another excellent measure in my opinion. By requiring men to face the ordeal of election to the Council of Elders near the end of life, he prevented neglect of high principles even in old age. Worthy of admiration also is the protection that he afforded to the old age of good men. For the enactment by which he made the Elders judges in trials on the capital charge caused old age to be held in greater honour than the full vigour of manhood. And surely it is natural that of all contests in the world this should excite the greatest zeal. For noble as are the contests in the Games, they are merely tests of bodily powers. But the contest for the Council judges souls whether they be good. As much then, as the soul surpasses the body, so much more worthy are the contests of the soul to kindle zeal than those of the body.

Again, the following surely entitles the work of Lycurgus to high admiration. He observed that where the cult of virtue is left to voluntary effort, the virtuous are not strong enough to increase the fame of their fatherland. So he compelled all men at Sparta to practise all the virtues in public life. And therefore, just as private individuals differ from one another in virtue according as they practise or neglect it, so Sparta, as a matter of course, surpasses all other states in virtue, because she alone makes a public duty of gentlemanly conduct. For was not this too a noble rule of his, that whereas other states punish only for wrong done to one's neighbour, he inflicted penalties no less severe on any who openly neglected to live as good a life as possible? For he believed, it seems, that enslavement, fraud, robbery, are crimes that injure only the victims of them; but the wicked man [the Greek here is actually "un-man" -- an-andron -- "unmanly"] and the coward are traitors to the whole body politic. And so he had good reason, I think, for visiting their offences with the heaviest penalties.

And he laid on the people the duty of practising the whole virtue of a citizen as a necessity irresistible. For to all who satisfied the requirements of his code he gave equal rights of citizenship, without regard to bodily infirmity or want of money. But the coward who shrank from the task of observing the rules of his code he caused to be no more reckoned among the peers.

~ translated by E C Marchant

So -- says Xenophon -- and these are the key points:

Like I said, the Greek, in Xenophon, for "honourable death" -- is actually "kalon thanaton" -- which translates as a "noble and beautiful death."

Both Marchant, writing in 1925; and Talbert, writing in 1988 -- say "honourable."

And that no doubt makes sense to a modern reader.

But anyone who understands the Greeks, and that very Greek concept, per Aristotle, of striving "to take possession of the beautiful" -- knows that a noble and beautiful death is what Xenophon means.

Here's Werner Jaeger's explanation of what exactly Aristotle meant by "to take possession of the beautiful":

...it is the highest kind of love which makes man reach out towards the highest areté: through which he 'takes possession of the beautiful'.

The last phrase is so entirely Greek that it is hard to translate. For the Greeks, beauty meant nobility also. To lay claim to the beautiful, to take possession of it, means to overlook no opportunity of winning the prize of the highest areté.

...Aristotle's own words are quite clear. They show that he was thinking chiefly of acts of moral heroism. A man who loves himself will (he thought) always be ready to sacrifice himself for his friends or his country, to abandon possessions and honours in order to 'take possession of the beautiful'. The strange phrase is repeated: and we can now see why Aristotle should think that the utmost sacrifice to an ideal is a proof of a highly developed self-love. 'For,' he says, 'such a man would prefer short intense pleasures to long quiet ones; would choose to live nobly for a year rather than to pass many years of ordinary life; would rather do one great and noble deed than many small

ones.'

These sentences reveal the very heart of the Greek view of life -- the sense of heroism through which we feel them most closely akin to ourselves. By this clue we can understand the whole of Hellenic history -- it is the psychological explanation of the short but glorious aristeia of the Greek spirit. The basic motive of Greek areté is contained in the words 'to take possession of the beautiful'. The courage of a Homeric nobleman is superior to a mad berserk contempt of death in this -- that he subordinates his physical self to the demands of a higher aim, the beautiful. And so the man who gives up his life to win the beautiful, will find that his natural instinct for self-assertion finds its highest expression in self-sacrifice.

The speech of Diotima in Plato's Symposium draws a parallel between the struggles of law-giver and poet to build their spiritual monuments, and the willingness of the great heroes of antiquity to sacrifice their all and to bear hardship, struggle, and death, in order to win the prize of imperishable fame. Both these efforts are explained in the speech as examples of the powerful instinct which drives mortal man to wish for self-perpetuation. That instinct is described as the metaphysical ground of the paradoxes of human ambition.

Aristotle himself wrote a hymn to the immortal areté of his friend Hermias, the prince of Atarneus, who died to keep faith with his philosophical and moral ideals; and in that hymn he expressly connects his own philosophical conception of areté with that found in Homer, and with its Homeric ideals Achilles and Ajax. And it is clear that many features in his description of self-love are drawn from the character of Achilles. The Homeric poems and the great Athenian philosphers are bound together by the continuing life of the Hellenic ideal of areté.

So: Xenophon is saying that Lycurgus "caused his people to choose a noble and beautiful death in preference to a disgraceful life."

And to Xenophon, as to the Spartans, a noble and beautiful death means first off a death found facing the enemy -- face-to-face and front-to-front -- a con-fronting -- not a running away.

"No retreat, no surrender."

Only a glorious victory or a noble death.

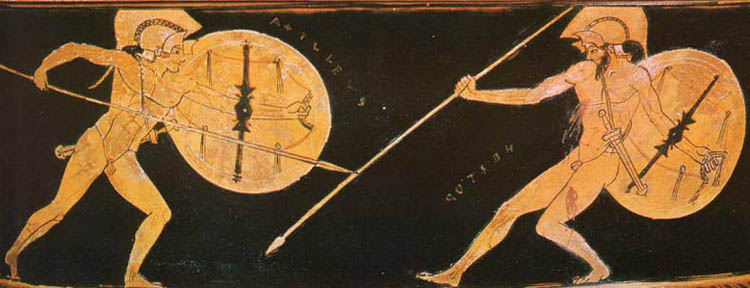

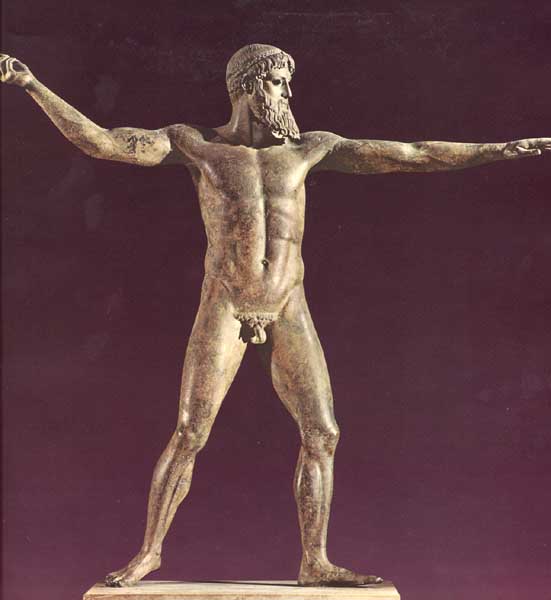

So: Hector has died honorably -- and nobly.

Please note that neither Achilles nor Hector are fighting for personal gain.

Hector is fighting to defend his city and family.

Achilles is fighting to avenge his dead lover, Patroclus.

The fight therefore is not about self -- it's about self-sacrifice.

And as Jaeger says, to the Greeks, "the man who gives up his life to win the beautiful, will find that his natural instinct for self-assertion finds its highest expression in self-sacrifice."

"his natural instinct for self-assertion finds its highest expression in self-sacrifice."

What is Man's "natural instinct for self-assertion?"

Aggression.

Man's natural aggression finds its highest expression in self-sacrifice.

And, in turn, self-sacrifice -- moral heroism -- is the highest expression of excellence.

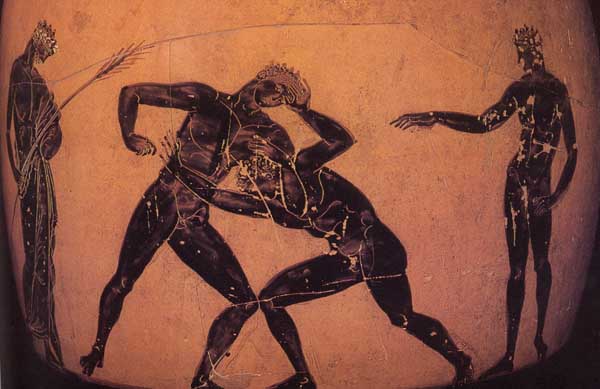

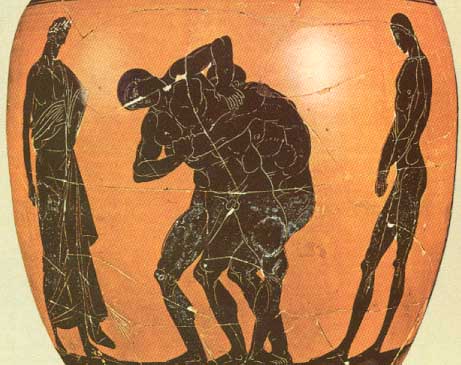

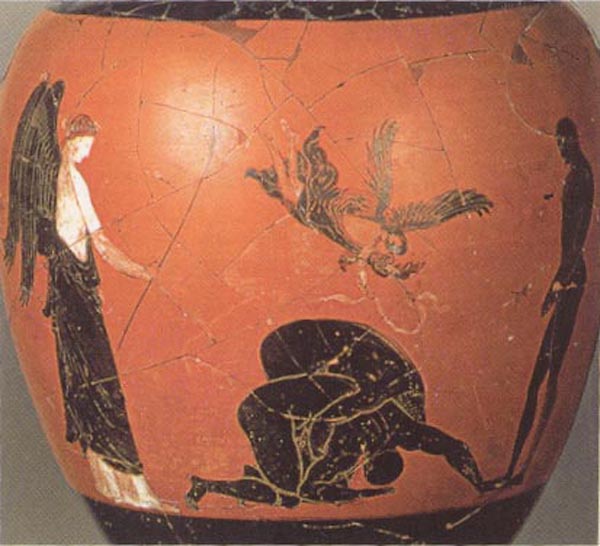

We see that all the time in Greek thought, and in Greek art.

For example, and as we've said, the word for noble -- "kalos" -- is also the word for beautiful.

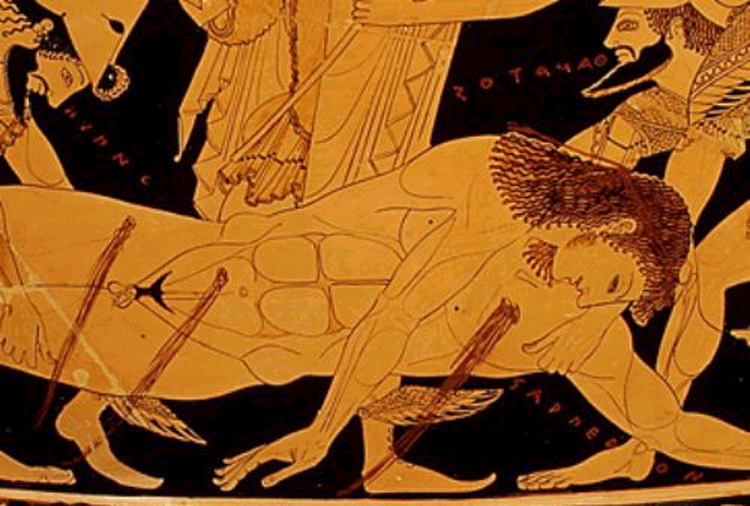

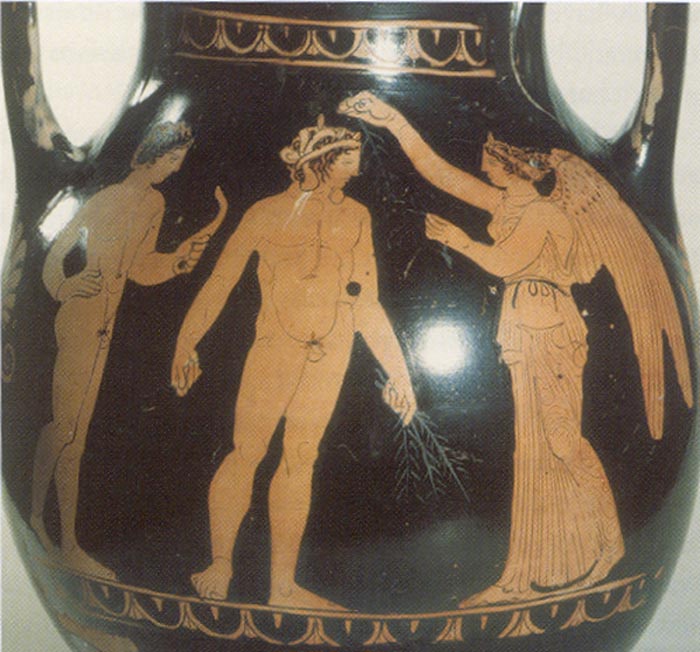

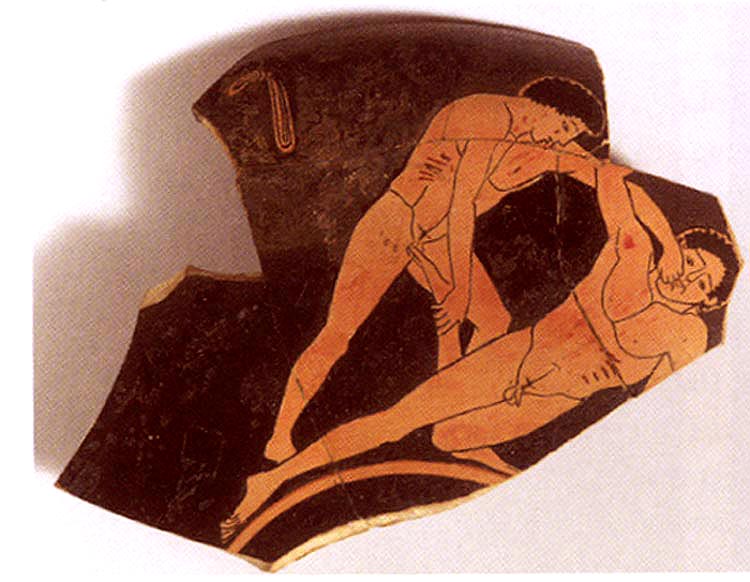

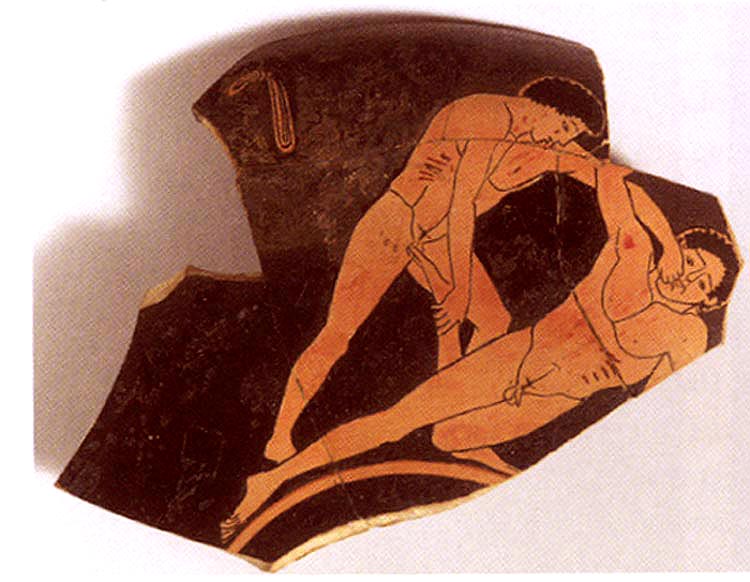

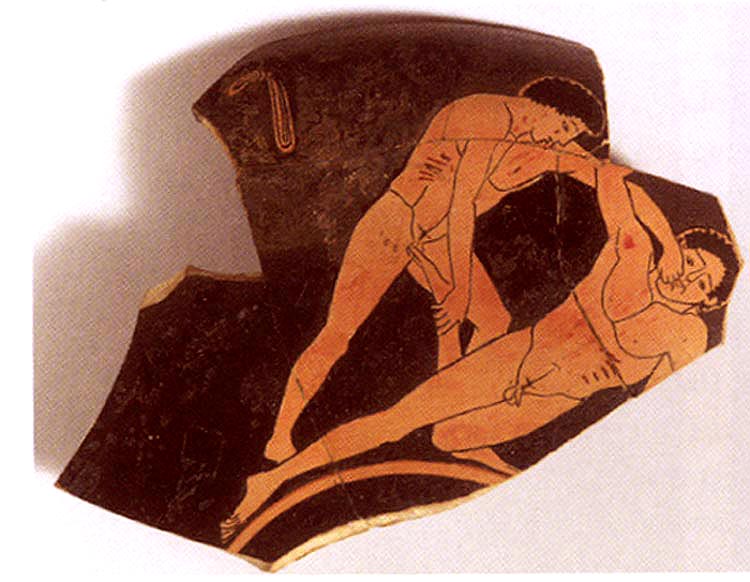

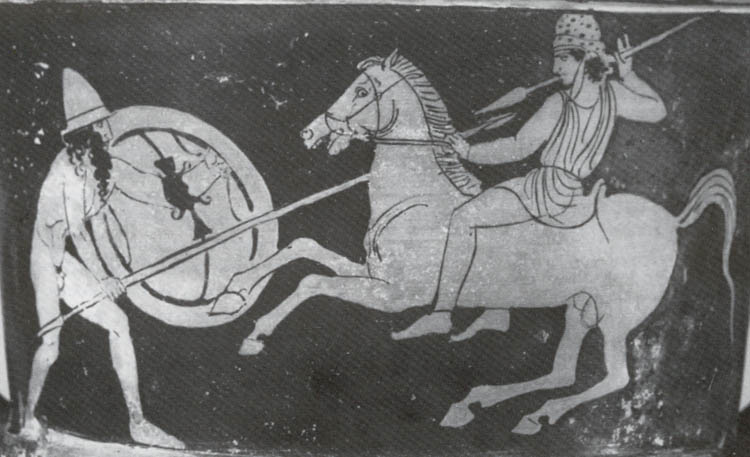

And when we look at this painting of Sarpedon, who's died heroically in battle at Troy, we can see that even in death he's still both noble and beautiful:

So -- a noble death is also a beautiful death.

Sarpedon, too, has sought to take possession of the beautiful -- and has succeeded.

Moreover, says Xenophon, who was a soldier first and foremost, those who choose to face the enemy are LESS likely to die than those who run away.

For "valour is actually easier and pleasanter and more resourceful and mightier."

And then Xenophon says something very striking:

"And obviously glory adheres to the side of valour, for all men want to ally themselves somehow with the brave."

And the word he uses for "valour" is of course areté; while "the brave" are "tois agathois" -- those who are both brave -- and good.

So: glory adheres to the side of valour, virtue, excellence, manhood;

While --

"All men want to ally themselves somehow with the brave."

All Men want to ally themselves with the brave.

Indeed they do.

We know that.

It's core to male psychology because it's core to male socio-biology.

Men -- ALL Men -- seek to be members of a Warrior group -- they seek to ally themselves with the Brave.

Warriorhood.

All Men want to ally themselves with the Brave.

That is a basic male and Manly need and desire which cannot be indefinitely or infinitely denied.

So -- Lycurgus made the life of the brave happy, and that of the coward miserable.

And, as we saw in my reply to Warrior Joe's You people are changing lives, the word for happiness is "eu-daimonia," meaning "having a good guardian spirit"; and the word for misery is "kako-daimonia," meaning "having a shitty guardian spirit."

"Kakos" -- the word for cowardly, evil, and ugly -- comes from "kakke" -- human waste, shit.

And when Xenophon says that Lycurgus made the coward's life miserable, in Greek it's expressed like this: the cowardly -- "kakos" -- had a life of "kako-daimonia" -- shitty misery.

Which was clearly deserved.

Yet in other city-states, says Xenophon, the coward -- someone who'd run away during battle -- remained integrated into society.

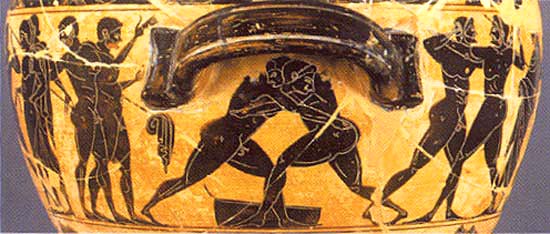

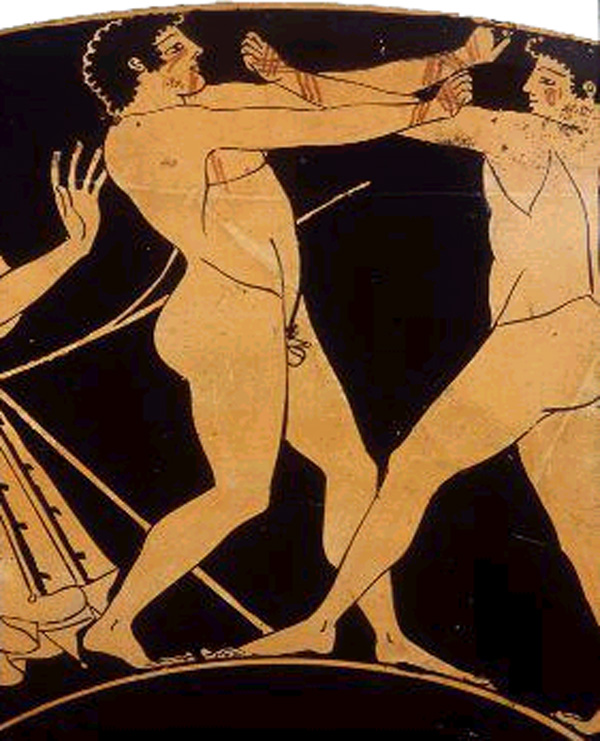

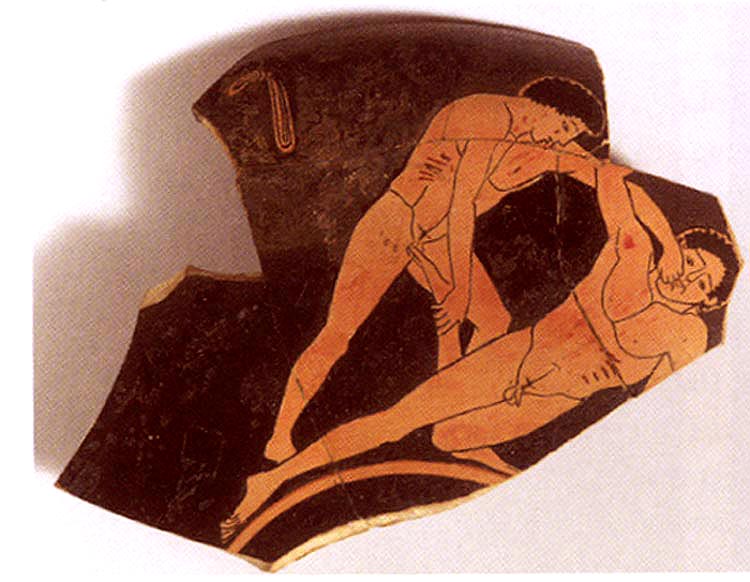

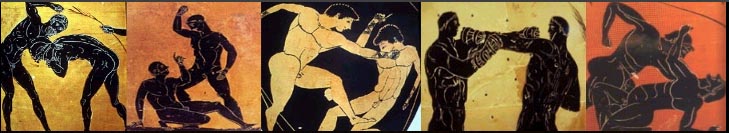

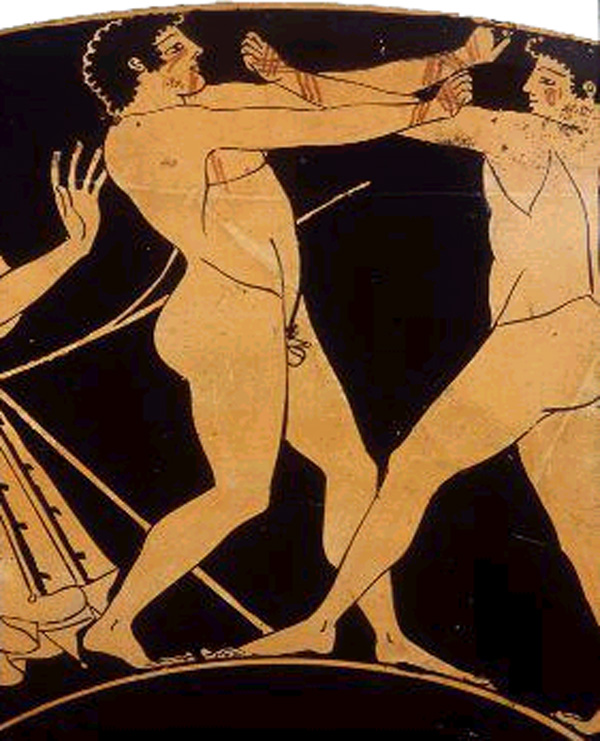

Whereas at Sparta, "everyone would be ashamed to have a coward with him at the mess or to be matched with him in a wrestling bout."

So -- not only would no one want to eat with a coward --

but no one would want to wrestle him either.

That too is a very striking statement.

Because it parallels the way we feel about having sex with a male who participates in anal penetration.

Why would you want to do that?

What's the point to wrestling --- or having sex with -- a male who displays that sort of unmanly behavior?

It makes no sense.

What we seek is the union of Man with Man.

The Manly with the Manly.

The Brave with the Brave.

Who would seek to be united with the UNmanly, the coward?

No MAN, of his own free will, would seek such a union.

Because ALL MEN want to ally themselves with the Brave.

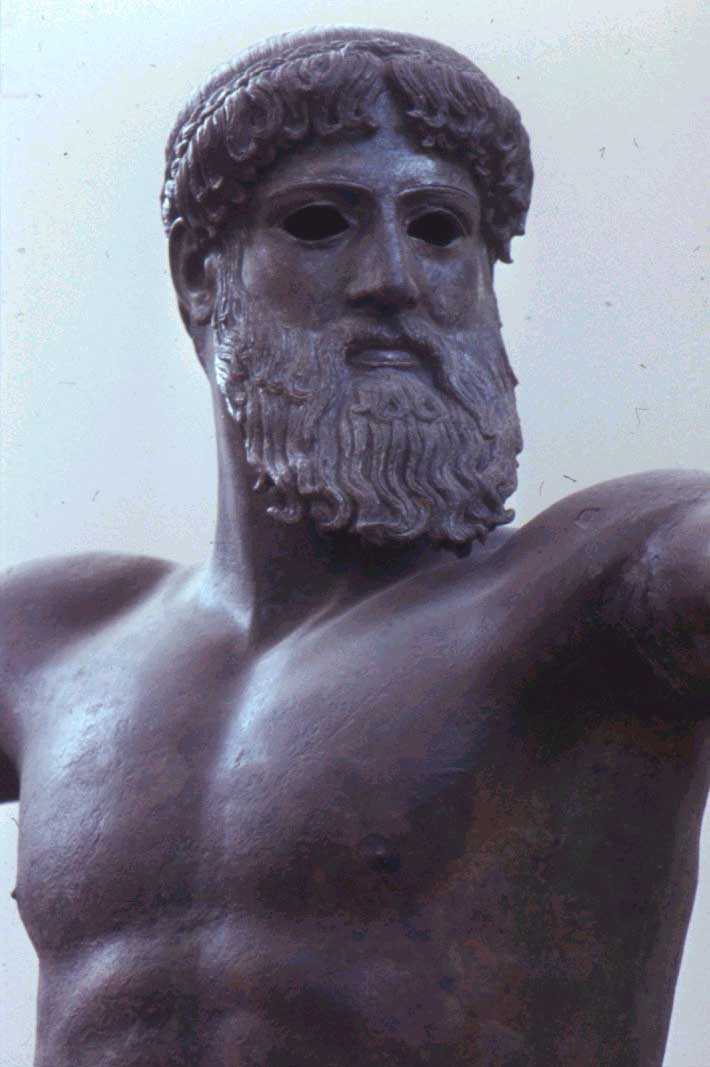

The Phallic.

The Martial.

The Honorable.

The Strong.

Phallus and Fidelity.

Strength and Honor.

That's what MEN want.

The mutual exaltation of Manhood which can only come through intimate, mutually genital contact with another MAN.

And while they may seek a Contest with that Man --

what they don't want is to obliterate him as a Man.

For then there can be no mutual exaltation of Manhood.

So -- at Sparta, not only would no one want to take a meal with a coward -- but no one would wrestle him either.

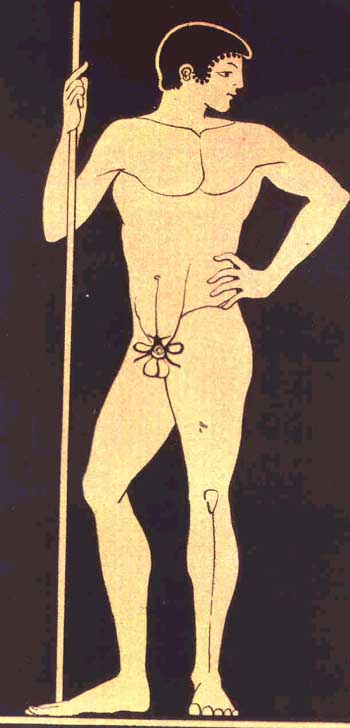

The skin-on-skin and genital contact of nude male wrestling is reserved for MEN -- and youths -- who are brave.

Who display a morally brave beauty.

That was through having a Council of Elders -- who were selected based on virtue aka areté; and through having those Elders judge capital cases.

Key point: to Lycurgus, the unmanly man and the coward are "are traitors to the whole body politic."

And so they are most heavily punished.

And you'll notice the very direct association between unmanliness and cowardice.

"kakon kai an-andron"

"kakos" = cowardly, shitty, evil; "kai" = and; "andros" = man, "an-andron" = un-man, un-manly

"kakon kai an-andron" = the coward and un-man -- the unmanly

Very clear to the Greeks.

The peers or equals -- the Greek is "hoi homoioi" -- and you see the word "homo" meaning same or equal -- the peers were the full-blooded adult male Spartans -- the Spartiatai.

What made you a peer was not money -- that's the key point.

What made you a peer was virtuous conduct -- areté.

Valour.

Manhood.

For the emphasis, in Xenophon's account, is on bravery vs cowardice.

The brave man remained a peer, even if he was infirm of body or poor.

The coward was, in effect, dis-enfranchised -- removed from the ranks of the peers.

He was ruined -- and suicide was often his only recourse.

So: Sparta was not about wealth.

Sparta was about Virtue; Manliness; Valour.

Which were seen, ultimately, as spiritual values.

Xenophon sums it up like this:

Is Xenophon telling the truth about all this?

Oh yeah.

The Spartans themselves said so.

And if we look at the Sayings of the Spartans, compiled by Plutarch ca 100 AD and which we first examined in the 300 message thread, we can see how the emphasis on virtue, and disdain for money, possessions, and greed, plays out:

When one of the Persians by persistent bribery had lured away the person Demaratus was in love with and was saying, "Spartan, I have hunted down your beloved," Demaratus replied, "By the gods, it's not you, it's the fact that you have bought him."

When amongst the spoils some people were amazed at the extravagance of the Persian's clothing, he said: "Better for them to be men of great worth rather than to have possessions of great worth."

After the victory over the Persians at Platea, he gave orders that the Persian dinner which had been prepared beforehand should be served to his staff. Since it was incredibly expensive, he said: "By the gods, with a spread like this what greedy characters the Persians were to chase after our barley-bread."

After Alexander the Great announced at Olympia that all exiles save Thebans [Thebes had resisted Alexander and had been destroyed by him] could go home, he said: "While this announcement is unfortunate for you Thebans, it is an honor nonetheless, since Alexander is frightened only of you."

When someone asked him how much property he owned, he said: "No more than enough."

He said to the man who asked why they wear their hair long: "This is the natural means of personal adornment, and it costs nothing."

When the ephors said, "Haven't you decided to take any action beyond blocking the passes against the Persians?", "In theory, no," he said, "but in fact I plan to die for the Greeks."

When Xerxes wrote to him: "It is possible for you not to fight the gods but to side with me and be monarch of Greece," he wrote back: "If you understood what is honorable in life, you would avoid lusting after what belongs to others. For me, it is better to die for Greece, than to be monarch of the people of my race."

~ Plutarch, Sayings of the Spartans

So: the Spartans, drawing on lessons learned at Lycurgus' knee, are quite consistent, and they're quite damning of the money-driven and greedy world around them:

"By the gods, it's not you, it's the fact that you have bought him."

"Better for them to be men of great worth rather than to have possessions of great worth."

Far better to be a Man of great worth than to have possessions of great worth.

"By the gods, with a spread like this what greedy characters the Persians were to chase after our barley-bread."

Barley was the mainstay grain of the ancient world, and usually the cheapest. Poor people -- and the Spartans -- ate "barley-bread," which was coarse; the rich had access to the more expensive wheaten-bread, which was considered more palatable and more desirable.

It's an honor -- not to be rich -- but to be feared by your enemies: "While this announcement is unfortunate for you Thebans, it is an honor nonetheless, since Alexander is frightened only of you."

Property? "No more than enough."

Long hair: "This is the natural means of personal adornment, and it costs nothing."

Greed: "If you understood what is honorable in life, you would avoid lusting after what belongs to others."

Greed -- greed is dishonorable.

Ugly.

Ignoble.

Virtue is what matters:

"I plan to die for the Greeks."

"For me, it is better to die for Greece, than to be monarch of the people of my race."

In saying that, and then indeed doing it, Leonidas "takes possession of the beautiful."

Jaeger:

...it is the highest kind of love which makes man reach out towards the highest areté: through which he 'takes possession of the beautiful'.

The last phrase is so entirely Greek that it is hard to translate. For the Greeks, beauty meant nobility also. To lay claim to the beautiful, to take possession of it, means to overlook no opportunity of winning the prize of the highest areté.

...Aristotle's own words are quite clear. They show that he was thinking chiefly of acts of moral heroism. A man who loves himself will (he thought) always be ready to sacrifice himself for his friends or his country, to abandon possessions and honours in order to 'take possession of the beautiful'. The strange phrase is repeated: and we can now see why Aristotle should think that the utmost sacrifice to an ideal is a proof of a highly developed self-love. 'For,' he says, 'such a man would prefer short intense pleasures to long quiet ones; would choose to live nobly for a year rather than to pass many years of ordinary life; would rather do one great and noble deed than many small ones.'

These sentences reveal the very heart of the Greek view of life -- the sense of heroism through which we feel them most closely akin to ourselves. By this clue we can understand the whole of Hellenic history -- it is the psychological explanation of the short but glorious aristeia of the Greek spirit. The basic motive of Greek areté is contained in the words 'to take possession of the beautiful'. The courage of a Homeric nobleman is superior to a mad berserk contempt of death in this -- that he subordinates his physical self to the demands of a higher aim, the beautiful. And so the man who gives up his life to win the beautiful, will find that his natural instinct for self-assertion finds its highest expression in self-sacrifice.

Μan's natural instinct for self-assertion -- for Aggression -- finds its highest expression in self-sacrifice.

Indeed.

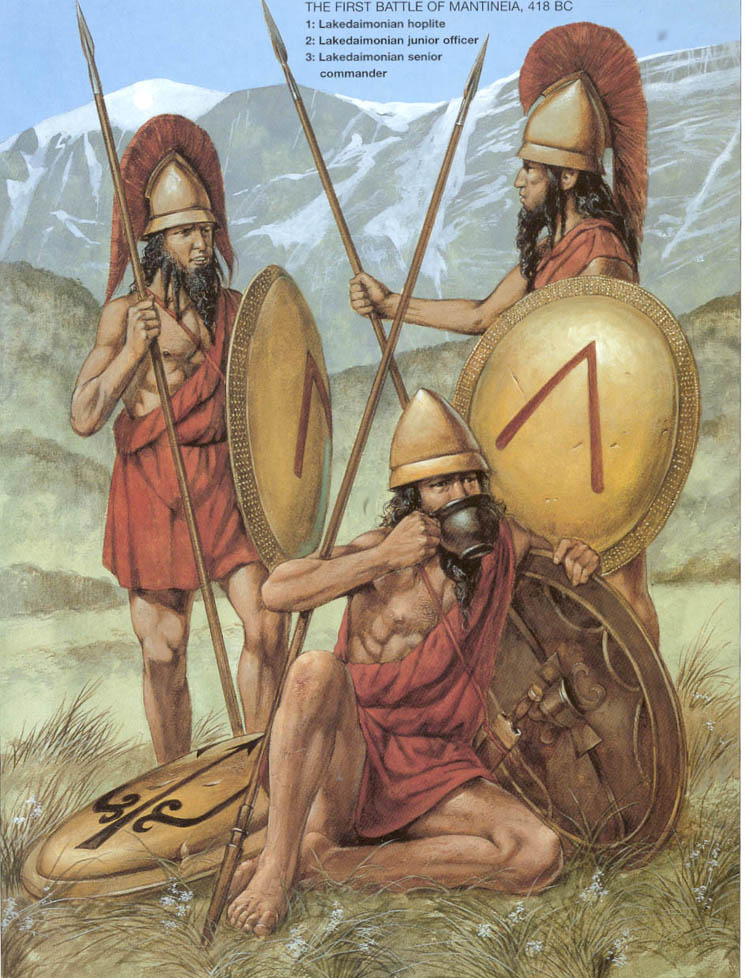

For in another section of his Constitution of the Lacedaemonians, Xenophon talks about the Agogé, and The Fighting of the Youths which was arranged and structured by Lycurgus:

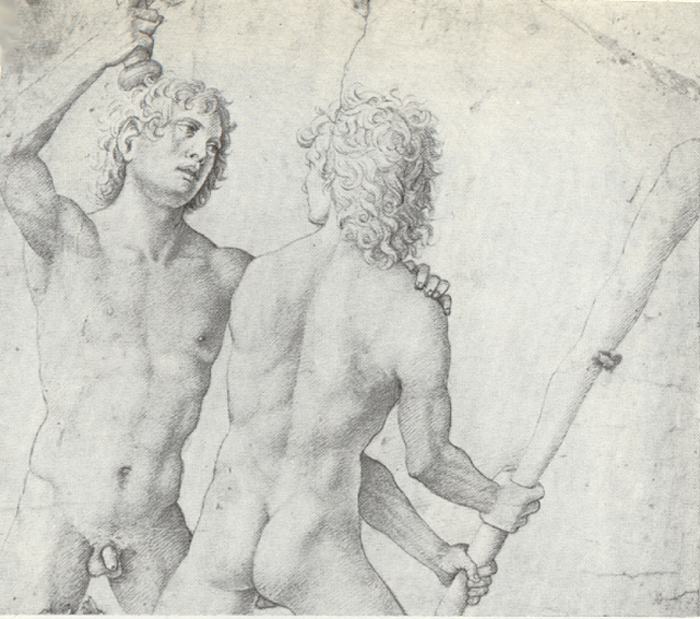

[Lycurgus] saw that where the spirit of rivalry is strongest among the people, there the choruses are most worth hearing and the athletic contests afford the finest spectacle. He believed, therefore, that if he could match the young men together in a strife of valour [eis erin peri aretes], they too would reach a high level of manly excellence. I will proceed to explain, therefore, how he instituted matches between the young men.

The Ephors, then, pick out three of the very best among them. These three are called Commanders of the Guard. Each of them enrols a hundred others, stating his reasons for preferring one and rejecting another. The result is that those who fail to win the honour are at war both with those who sent them away and with their successful rivals; and they are on the watch for any lapse from the code of honour.

Here then you find that kind of strife that is dearest to the gods, and in the highest sense political -- the strife that sets the standard of a brave man's conduct; and in which either party exerts itself to the end that it may never fall below its best, and that, when the time comes, every member of it may support the state with all his might. And they are bound, too, to keep themselves fit, for one effect of the strife is that they fight whenever they meet; but anyone present has a right to part the combatants.

~ translated by E C Marchant

When we look at the language in this passage, it's very striking.

Lycurgus, we're told, believed that "if he could match [symballoi] the young men [hebontas] together in a strife of valour [eis erin peri aretes], they too would reach a high level of manly excellence [andragathia -- manliness, valour]."

These are "young men" -- hebontas -- or youths.

They are "matched together" -- and the Greek, symballoi, can mean throw or mix together, fight, incite --

and there we have shades of Statius' "nudamque lacessere pugnam" -- "incite to nude fight" -- which we discussed in our first Agoge article.

So -- these young men are incited -- "matched together" says Marchant --

in a "strife of valour" -- and the Greek is erin peri aretes -- a strife among the excellent, a strife of the virtuous --

A Strife of Valour says Marchant.

And through that strife, the men attain a high level of "manly excellence."

The Greek word is "andragathia," which combines "andros" -- man or manly -- with "agathos" -- good and brave.

So anadragathia can be thought of as manly goodness -- or -- brave manliness.

Manly excellence says Marchant.

Lycurgus, then, intends that the *best* young Men of Sparta be incited into a Fight, a Combat, a Strife of Virtue, a Strife of Valour, which will produce in them the highest level of manly good and manly excellence.

This kind of strife, says Xenophon, and which we should note is true strife -- the two groups "fight whenever they meet" -- "is dearest to the gods, and in the highest sense political -- the strife that sets the standard of a brave man's conduct; and in which either party exerts itself to the end that it may never fall below its best, and that, when the time comes, every member of it may support the state with all his might."

So Xenophon -- and of course Lycurgus -- sees Fighting as a path to excellence, to virtue, to moral heroism.

As did all Greeks.

For it "sets the standard of a brave man's conduct."

"A brave man."

At Sparta, says Xenophon, and as *designed* by Lycurgus, a Brave Man learns "that his natural instinct for self-assertion finds its highest expression in self-sacrifice."

Again, what's vital to understand is that this is by design.

The Strife of Valour is part of the Agogé, and was designed by Lycurgus, the Spartans and Xenophon believed, to teach the young Men to excel, to excel in the Fight, and to never fall below their best, so "that, when the time comes, every member of it may support the state with all his might."

To Fight with all their Might.

Not for themselves, but for their Warrior band, and, ultimately, for Sparta.

To Fight with all their Might.

For each other, and for an ideal.

The ideal that was Sparta.

And that they would Fight with all their Might was exactly the sort of thing that would appeal to Xenophon, says Jaeger, because he was the sort of man who when he did anything in his life, did it all-out -- with all his soul and all his strength.

Now -- who was Xenophon?

A pro-Spartan Athenian aristocrat who joined an expedition to overthrow the King of Persia, led 10,000 Greek mercenaries as they fought their way out of Persia after the coup failed, and was eventually awarded an estate by the Spartans, he was, says Werner Jaeger, "the purest embodiment of his age":

So -- Xenophon was basically a military man; he joined a mercenary army and ended up leading it, in great peril, out of Persia, after the coup which was its raison d'etre, failed.

His leadership of that army brought him first to the attention of the Spartans and then within the Spartan orbit; and he ended up banished from Athens and living on an estate which the Spartans had given him.

There he lived the life of a gentleman farmer -- and wrote a great many books.

Says Jaeger:

Xenophon thinks the soldier is the ideal man: fresh and healthy, honest and brave, disciplined not only to resist the elements and the enemy but to conquer his own weaknesses. In a world where the framework of politics and civil security is collapsing, he is the only free and independent man. Xenophon's ideal soldier is not an arrogant domineering fellow who tramples rough-shod over conventions and laws, and violently slashes through every Gordian knot. ... [Rather, he relies on] the love of his friends and the trust of his people. Xenophon's soldier is a man of simple faith in God. ... But also he thinks of soldiering as the best education for a truly noble man.

...

His criticism of contemporary Athenian democracy often comes out in the Memorabilia, despite his patriotic loyalty to his homeland; and it makes him admire many things in Sparta, the political opponent of Athens, which he holds to be wise solutions for problems left unsolved in Athens. All the woes of the democracy of his own time seemed to him to flow from one source, the exaggerated self-assertion of individuals, who appeared to think that citizens of a democracy had no duties, only privileges, and who believed that the essence of liberty was to have these privileges guaranteed by the state. With his ideals of strict soldierly discipline, Xenophon must have found the lack of a sense of duty and responsibility particularly repulsive.

His political thought started not with the individual's claims to

attain his own personal ideals, but with the external conditions that made it possible for the community to exist. The fault for which so many contemporary thinkers criticized the Athenian democracy, the reluctance and inability of its citizens to fight for their country in the midst of a world full of hostility and envy, must have looked to him like preposterous and childish folly, which would soon deprive Athens of the liberty she vaunted so proudly.

...

The "Spartan ideal of civic virtue," says Jaeger, stands, for Xenophon, in stark contrast to the Athenian lack of a sense of civic duty and responsibility:

...In brief, [the Spartan ideal] was that the citizen's greatest contribution to the common good was to join in the defence of his country, and that his rights in the state should be measured, not by privileges of rank or wealth, but by his valour in fulfilling this supreme duty.

Since the Spartan community always had to fight, or to be ready to fight, for its life, this basic conception of the relation between individual and state was never challenged. In the course of centuries it developed its own peculiar system of communal life. (We have no information about the various stages of the development. In the age of Xenophon and and Plato, and indeed long before them, the Spartan cosmos was finished and complete. But it is entirely because of the interest in Spartan paideia which was felt by writers like Xenophon, that any valuable historical information about Sparta has survived.)

The rest of the Greeks saw with astonishment and admiration how every institution in Sparta served the same purpose -- to make Spartan citizens the best soldiers in the world. They understood very well that this was not done by incessant drilling and manoeuvring, but by moulding the character from earliest childhood. This education was not only military. It was political and moral in the broadest sense ...

...

Spartan discipline ... was built into the legislative structure of the state, which, according to Xenophon, was the work of one single genius, the half-mythical Lycurgus. ... [Xenophon] treats the Spartan cosmos as a political work of art, complete in itself; he praises its originality, and believes it a model for others to imitate. ... Sparta was for Xenophon the embodiment of the virtues of Cyrus' camp, in a whole great Hellenic state.

So -- Xenophon was an Athenian who'd been brought into close contact with Sparta by an accident of his history.

From his point of view as a soldier, the Athens of his day suffered from "the exaggerated self-assertion of individuals, who appeared to think that citizens of a democracy had no duties, only privileges, and who believed that the essence of liberty was to have these privileges guaranteed by the state."

Sound familiar?

In other words, there'd been a loss of communal values.

Values which Sparta had retained.

While Athens suffered from "the reluctance and inability of its citizens to fight for their country in the midst of a world full of hostility and envy," -- which to Xenophon looked like "preposterous and childish folly, which would soon deprive Athens of the liberty she vaunted so proudly."

Does that sound familiar?

In the US, we no longer have conscription.

Instead, we have a volunteer military.

Which means that we've de facto privatized and out-sourced Courage.

In the US, Courage is for suckers.

The wealthier classes buy the Courage of the poorer classes, who are sent off to fight and die in wars about which the electorate is divided, and to which they're reluctant or just plain unwilling to commit their own bodies.

That, as Victor Davis Hanson, author of the definitive study of hoplite warfare, points out, is suicidal for a democracy.

A few months back, Russia, which is supposed to be a defunct power, decided to march into Georgia.

Russia has conscription.

Russia was easily able to muster the forces needed to crush Georgia,

while, at the same time, thumbing her nose at the West.

Although Georgia is allegedly an American ally, America, whose military has trimmed down, and which is bogged down in two wars in the Middle East which, many observers have said, have left her dangerously over-extended --

made no attempt to aid the Georgians militarily.

Like I said, America no longer has conscription.

And a significant part of the American elite is deeply suspicious of the military.

Again, our society tends to work against communal values.

Warrior values.

For example, the New York Times ran an article in October about suicide rates among soliders.

Army and Agency Will Study Rising Suicide Rate Among Soldiers trumpeted the headline.

Yet when you looked at the fine print -- there was no there -- there:

By LIZETTE ALVAREZ

Published: October 29, 2008

...

Suicides in the Army have been climbing since the 2003 invasion of Iraq. In 2007, 115 soldiers killed themselves, a rate of 18.1 per 100,000 people, or 1 percent lower than the civilian rate.

Of the 115, 36 soldiers killed themselves while deployed overseas, 50 had deployed at some point before the act and returned, and 29 had never deployed. Only a fraction had a prior diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder.

...

So: The theory is that being in the army and/or experiencing war cause suicide.

Do they?

The numbers don't support either.

First off, the army's over-all suicide rate is LOWER than the civilian rate.

That suggests that the army is actually more cohesive and does a better job of preventing suicide than society at large.

And then there's the fact that of the 115 suicides in 2007, 29 were of folks who'd never deployed.

They were never at war.

So the actual rate of suicide in the army among soldiers who've been at war -- is SIGNIFICANTLY lower than the civilian rate.

Do the math.

On my calculator, it comes out to 13.53565217% -- 13.5%.

That's a lot lower than the general civilian rate of 19.1%

DUH.

Faced with those figures, if we were to be intellectually honest, wouldn't we have to conclude that going to war actually decreases your chance of committing suicide?

Yes, Bill, we would.

If the suicide rate, among males of a certain age, is significantly -- almost six points or 33% -- higher among the general population that it is among males who've enlisted in the army and gone to war --

then being in the army and deploying to a war zone actually decreases your chances of committing suicide.

What's really going on here, besides the Times' reflexive desire to print anything which can be construed as critical of the military?

Well, as I discussed in the ledger thread, the Times had run another article earlier this year, complete with lurid graphic

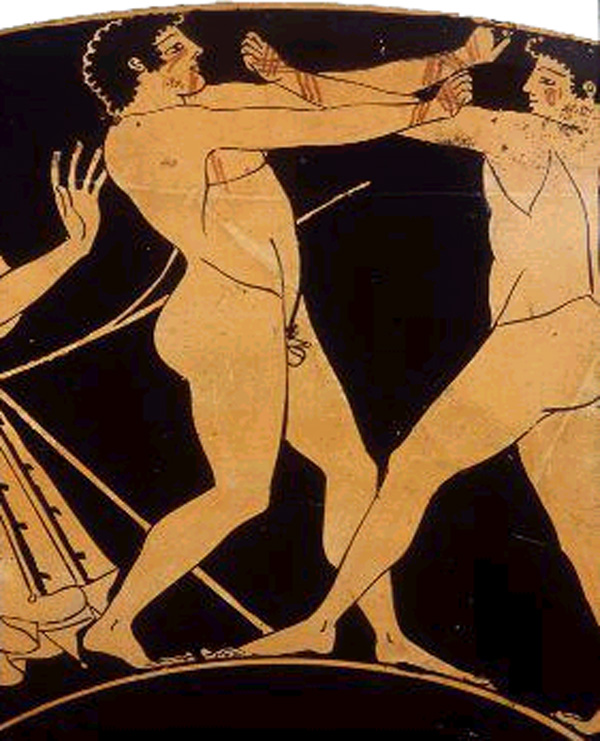

which spoke breathlessly about homicides committed by veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The implication in the Times' article was clear:

Soldiers learn to kill while overseas -- and then come home and keep killing.

Once again, the implication was clear -- it's dangerous to teach men how to kill -- even in defense of their country.

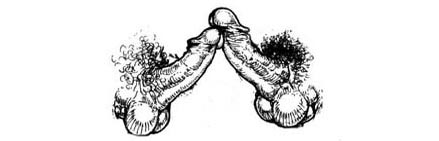

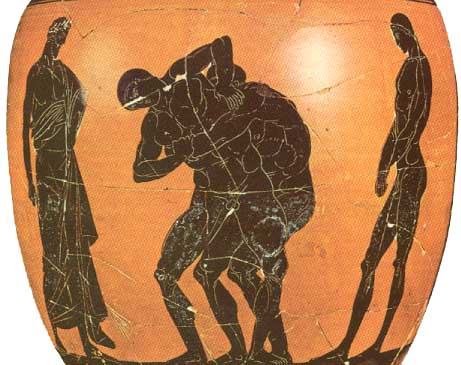

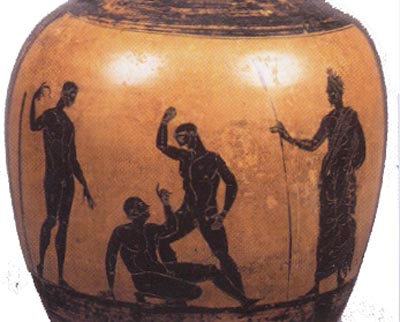

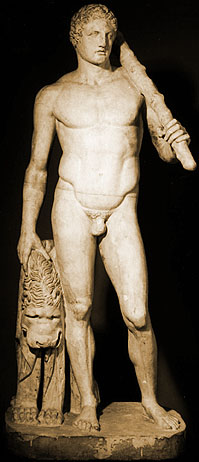

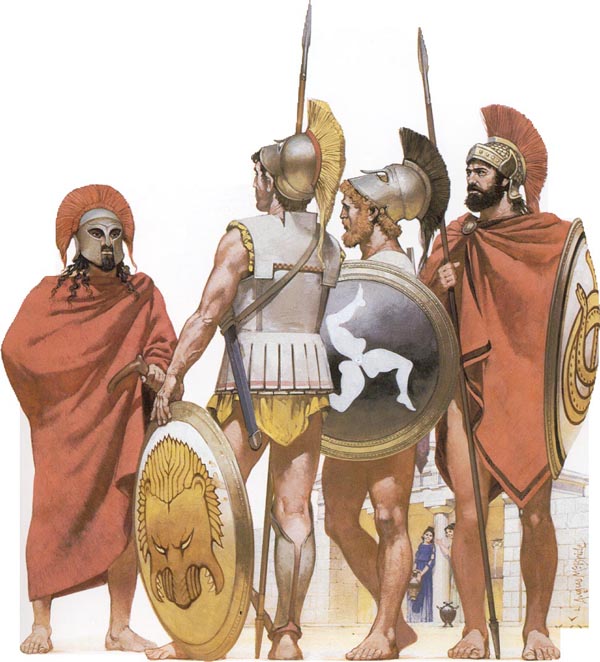

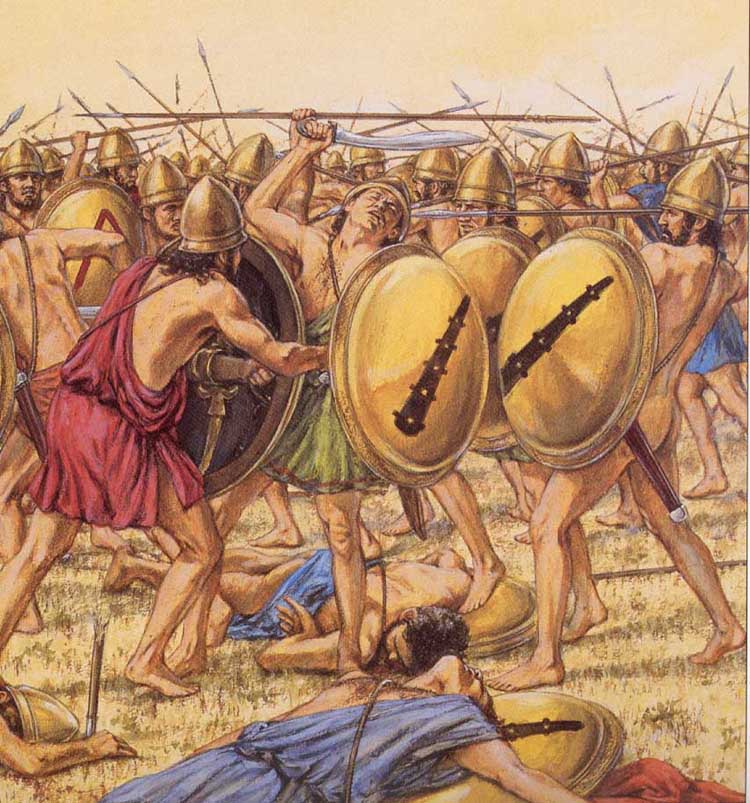

Look again at the picture:

Would you give any one of these maniacal males a gun?

Yet, if you did the math with that article, it turned out that, once again, the homicide rate among returned veterans was significantly lower than among males the same age in the general population.

Which would have to lead you to conclude that war -- and/or service in the military -- actually decreases homicidal tendencies.

Is that true?

I don't know.

As Patrick said to me, the people who go into the military, come out, and commit a homicide, are people who should never have been in the military in the first place.

They don't fit in.

And they don't fit in to civilian life either.

But the fact, so helpfully uncovered by the Times, that soldiers who've seen duty in a war zone are LESS likely to commit suicide and/or homicide than their peers in the general population, suggests to me that the "male bonding" -- the Warrior bonding -- which takes place among Men at War is healthy -- and life-giving.

In large part because it's communal.

So maybe our crazed American anti-Warrior individualism -- and its contempt for Courage -- isn't always the answer.

In point of fact, the US has abandoned all four of the Divine Virtues.

Justice is a function of wealth.

Courage, like I said, is for suckers.

Self-control? Nowhere to be found.

Piety, too, and like courage, is generally regarded as suitable only for suckers.

Religious-right pastors manipulate piety for personal gain and societal power.

And more than a few of those pastors preach a "prosperity gospel" which, because it equates worth with wealth, would have been incomprehensible to Jesus -- and just about every other thinker the world has known; and which consitutes its own form of dollar-worship.

Yet there was a time, not so long ago, when entire cultures were governed, and governed successfully, by these four virtues:

Courage

Justice

Self-control

Piety and Wisdom

And the most successful of those societies, like Sparta, understood that you have to devote all of your energies to those values, and to your society.

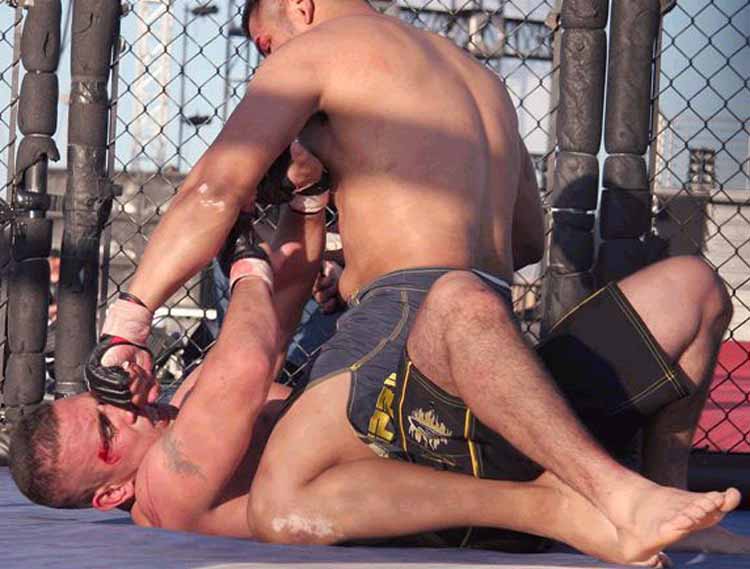

And they understood too that for a society to marginalize Valour -- Courage -- as we do both with the military and with fight sports like mixed martial arts --

and to actually underwrite "the reluctance and inability of its citizens to fight for their country in the midst of a world full of hostility and envy" --

is "preposterous and childish folly," which could only end by depriving its citizens of their independence, their liberty, and, yes, their prosperity too.

ωhat does any of this have to do with Brian?

A LOT!

Because he understands.

He says:

The credit crunch can crunch away, but it will NOT crunch my Manhood my Masculinity or my Warriorhood and it will not stop me sending my donations to the Alliance, because I hunger for the establishment of (through setting up of Regional Chapters by Warrior couples) a Warrior Community and that can only happen if we are committed to the cause of Warriorhood in every way we can be, and this includes sending as much in donations as often as we can.

So: Look at what Brian says:

1. We're building a new culture based on "a new type of love and belief that involves total Manly love, physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual."

2. "I hunger for the establishment of (through setting up of Regional Chapters by Warrior couples) a Warrior Community and that can only happen if we are committed to the cause of Warriorhood in every way we can be, and this includes sending as much in donations as often as we can."

Which means that

We're founding our culture and our community based on "total Manly love, physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual" -- which is correct; and,

The establishment of that community "can only happen if we are committed to the cause of Warriorhood in every way we can be."

Which is also correct.

Because, it so happens, that's how the Spartans were.

They were committed to the sacred cause of Warriorhood in every way they could be.

They were devoted to the communal values of Sparta, and they saw to it that every institution in their city, their community, furthered those values.

They did away with inequalities of wealth, because to them those inequalities were the product of greed, and served only to divide and weaken the city.

They did away with luxury of any sort, even in food.

Instead, they instituted communal messes, which kept their Men healthy while further strengthening their Warrior bonds.

They made the education of the young a communal task.

Children were not handed off to slaves or tutors.

Rather, every adult Spartan was expected to take part in their training.

That training was both physical and moral.

Jaeger: The Spartans were "moulding the character from earliest childhood. This education was not only military. It was political and moral in the broadest sense ..."

So: The education of the young was based on Fighting and the cultivation of Fighting Spirit;

*and* on areté -- excellence -- kalokagathia -- nobility and goodness -- andragathia -- manly excellence -- Manhood.

Qualities which are, ultimately, spiritual.

The physical and the spiritual came together in many places, including the great religious-athletic festivals, The Fighting of the Youths in Plane-Tree Grove, and in what Xenophon calls The Strife of Valour -- The Strife of the Virtuous --

"the strife that sets the standard of a brave man's conduct; and in which either party exerts itself to the end that it may never fall below its best, and that, when the time comes, every member of it may support the state with all his might."

It was this strife which set the standard of a brave man's conduct.

And which involved Fights between two groups of young Men.

These Fights and this Strife of Valour have to been seen in the essentially agonistic context of Greek life.

Greek life was organized around the Agon -- the Contest: one man's strenuous physical struggle to overcome another.

So: Men fought.

In any fight, there's a winner and a loser.

What's important to understand, however, was that the Greek Fighter, the Warrior, did not seek to obliterate his opponent.

The Fights were conducted, as such Fights are conducted today, in a spirit of mutual respect and camaraderie.

In which it was recognized, as Jaeger says, that the two combatants in this strenuous physical struggle were