Hail Warrior!

Welcome to Biblion Pempton -- Book V -- of Manhood: A Lexicon.

My name is Bill Weintraub, and I'm the creator of The Man2Man Alliance and Ares is Lord websites, and the author of Manhood: A Lexicon.

Manhood: A Lexicon is, basically, a book -- masquerading as a webpage.

And, like any book, it's best read from the beginning.

So -- I strongly encourage you to read, if you haven't already, the Prefatory Note and Prolegomena to Manhood: A Lexicon ;

And then Biblion Proton ;

Followed by Biblion Deuteron, Biblion Triton, and Biblion Tetarton.

It's important that you read that material, and in that order:

Doing so will not only greatly aid your understanding of the material you encounter in Biblion Pempton and the rest of Manhood: A Lexicon -- but is essential to your understanding that material.

Translation :

You won't be able to understand Biblion Pempton -- Book V -- without having first read the Prolegomena and the first four books.

Similarly, if you've already read that material -- but it's been a long time since you re-read it -- you'll need to review it.

For example :

Can you explain the difference between the world of becoming and the World of Being?

You have to be able to.

Can you tell me who Shorey, Jaeger, Jowett, and Lendon are?

Or Xenophon?

Or Arrian?

Or Aristonicus?

You have to be able to.

The material in Biblion Deuteron regarding being vs becoming is particularly important.

But so is your ability to explain the difference between the definition of Manhood in ancient Greece and its definition in contemporary America.

So :

You need to read -- and if you've already read once -- to review.

Now :

Biblion Pempton -- Book V -- which is titled Warrior Kosmos, Warrior Sanction /

Ares Hypostatized : Manhood is God -- is divided into ten chapters, of which the first two are being published today, January 30, 2014 :

I ARES: Manliness is Godliness

II ARES: High-Minded Passion and Noble Anger

Future chapters will be announced on this page, and on the Personal Stories message board.

Again, it's important that you read all ten chapters, and in the order given, starting with these first two :

I ARES: Manliness is Godliness

II ARES: High-Minded Passion and Noble Anger

Throughout all five books of the Lexicon, there appear translations of ancient Greek texts.

Certain words within the texts are indicated with brackets and a link, thus :

Whenever you see a bracketed link of that nature, it's essential that you click on it and read the definition given.

I repeat :

Not once, but every time you see the word, until you are 100% absolutely and without a doubt confident that you know exactly and precisely what the word means, you MUST click on and read the link.

Doing so is particularly important for the words we discussed in Parts II and III of Biblion Proton : The Alphas of Male, including Andreia, Arren, Aristos, Areté, etc ; and Men of Honor : The Morally Beautiful, the Righteously Erect, and the Warrior Worthy : Kalos-Kalon-Kala, Orthos, and Timé.

However, every word in the Lexicon is important -- and all bracketed links must be read.

Here's an example of why -- from Plato's Symposion :

Sokrates :

~Plato. Symposion. 212b, translated by Lamb.

The first bracketed link is of [timao] -- a word which greatly matters because it's derived from Timé -- Worth.

Warrior Worth.

So -- the first sentence should read "I tell you now that every Man should deem Love Worthy" ; and the word "Worthy" is important because it's a Warrior Word which, in this context, connects Romantic, Passionate Love between Men -- with the Warrior Worth -- the Timé -- Men earn through their Prowess on the Battlefield -- through their Prowess in Fight.

Again :

The first sentence should read "I tell you now that every Man should deem Romantic, Passionate Love between Man -- Worthy" ; and the word "Worthy" is important because it's a Warrior Word which, in this context, connects Romantic, Passionate Love between Men -- with the Warrior Worth -- the Timé -- Men earn through their Prowess on the Battlefield -- through their Prowess in Fight.

In other words, Sokrates' use of the word Worth -- Warrior Worth -- very explicitly connects Romantic, Passionate Love between Men -- with -- FIGHTING.

And in so doing, connects that Love with the Warrior Worlds of both Warriordom and Warrior Kosmos.

In short, timao matters.

But the other words matter too -- a LOT.

Why?

Here's Lamb's translation of the second clause :

And here's the actual meaning of that second clause :

both now and always do I praise as one would a conquering hero [enkomiazo -- see enkomios], the Might [dynamis] and Manliness [andreia] of Romantic, Passionate Love between Men [Eros] -- as far as I am able.

Hopefully you can see the difference between Lamb's translation and the actual meaning of the second clause, and understand therefore why it matters that you learn the actual meaning of ancient Greek words.

You'll notice that Lamb has translated andreia as "valor," when its actual meaning is Manhood, Manliness, Manly Spirit.

Does that mean Lamb has done something bad or wrong?

No -- not within the context of when he was writing -- ca 1925 -- and the Men he was writing for.

But he has, inadvertently, done something injurious to males like yourselves, who not only don't know how to Fight, but are completely ignorant of the ancient Greek and Roman, Fighting-Manhood-based, Ethical System.

We'll discuss that system throughout Biblion Pempton.

In the first two chapters of Biblion Pempton, we examine, among other matters, two variants of the system :

In Chapter One, the Involved or Integral Virtues of Manhood, Piety, Temperance, and Manly Moral Order ;

and, in Chapter Two, the more common variant, which puts MANHOOD and its attributes at the center and core of that system.

It's essential that you understand BOTH variants.

The idea of the Four Integral Virtues is simple : There are Four Virtues -- Manhood, Piety, Temperance, and Moral Order -- and you can't have one without having the other three.

The Manly Man is Pious, Temperate, and Morally Ordered ;

The Pious Man is Manly, Temperate, and Morally Ordered -- etc.

In the Manhood System, which, again, was certainly more common in ancient thought, Manhood, Fighting Manhood, is at the Moral Center of Society -- the Warriordom -- and of the Kosmos -- both created -- Fight is the Father of All -- and eternal -- the Warrior World of Being, the Warrior Kosmos.

Fighting Manhood has attributes -- one classicist names fifteen -- which every Man Struggles to Attain -- so as to Perfect his Manhood.

Put differently, the Perfect Man, the Man every male should strive to be, has all of the positive and active attributes of Fighting Manhood :

You should memorize both the Four Integral Virtues and what we can call the Four V's of Fighting Manhood -- Vigor, Valour, Virtue, and Value -- along with all their attributes of Strength, Excellence, Fortitude, etc. ;

And then, as you read, keep the two systems constantly in mind.

And to help you better understand the second of the systems, which again we call the Manhood System, I've written a small article with a long title, Understanding the core position

and actual meaning of Andreia-Areté-Virtus within the Culture of

Fighting Manhood, which I encourage you to read.

Finally, and once again, it's important that you read the entire Lexicon, beginning with the Prefatory Remarks and Prolegomena, and ending with this Biblion Pempton, and in the order given.

January 30, 2014

BIBLION PEMPTON

By Bill Weintraub

Chapter List :

I ARES: Manliness is Godliness

II ARES: High-Minded Passion and Noble Anger

BIBLION PEMPTON

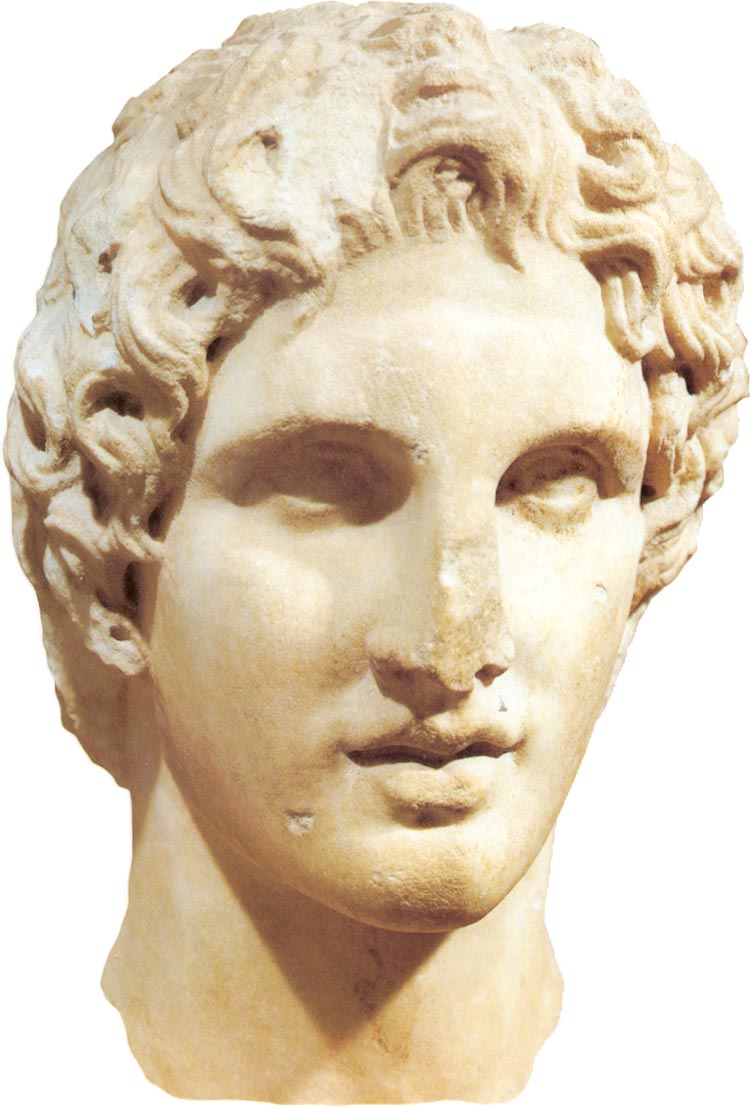

ARES: Manliness is Godliness

By Bill Weintraub

ωe begin with a new word and phrase, and a very important one for our subsequent discussion:

So:

Liddell and Scott define Homoiosis as "a being made like" and then add, immediately, "Theo" -- that is, God -- referring the reader to Plato's Theaetetus 176b, in which the phrase Homoiosis Theo means:

to become like God

ομοιωσις Θεω

~Plat. Theaet. 176b, translated by Fowler.

And that, according to Plato, is the goal of ALL philosophy -- that the individual, as much as possible, become like God.

But what, then, is God like?

Plato :

"to become like God, so far as this is possible," says Fowler ;

"Become like to God as far as may be" -- says Shorey.

To become like to God is to become "Dikaios" -- which, as we saw in Biblion Tetarton, means righteously well-ordered -- that is, well-ordered in a Manly way: the word refers, de facto, to a Manly Moral Order -- which means that to be Manly, according to Plato, and as I said at the end of Biblion Tetarton -- is to be like to God ;

And then there's

"Hosios" -- holy and pious -- and readers of the discussion of hybris in this Lexicon know that Greek Warriors, and in particular the Spartans, who were without question the Manliest of the Greek Warriors, were very pious ;

And,

"Phronesis" -- again, Phronesis is actually defined as purpose, intention, thoughtfulness, prudence -- Fowler says "wise," and that's fine in context, but the word is obviously related to sophrosyne -- which is the distinctly Manly quality of temperance, prudence, moderation, sensible and purposeful living -- in short, Manly Self-Control.

So:

Virtue, as we saw in the last section of Biblion Tetarton, In Union With Valour -- Virtue, canonically and to the Greeks, has four components, each of which is "involved," as Paul Shorey puts it, with the other three:

And you'll notice, first off, that each of the virtues has at least two words which characterize it, eg Piety / Wisdom.

Piety / Wisdom is actually one virtue -- Plato sometimes uses one word or the other, but clearly, given that Plato has said that we should seek to become like God, he's very religious -- indeed, he was far more religious than most of the philosophers who'd preceded him --

Which means that to him, Wisdom and Piety are virtually the same thing.

And that's so with the other three as well:

Self-Control / Temperance -- they're the same deal ;

Justice and Moral Order -- if you've read Biblion Tetarton, you understand that Justice is the result of a Moral Order, indeed of a Manly Moral Order, a Moral Order suffused with Fighting Manhood -- and that within such a Manly Moral Order, Justice is a given ;

And, of course, that Manliness is Fighting Manhood.

So -- those nine or ten words signifying Piety, Temperance, Moral Order, and Manhood, make up the Four Canonical Greek Virtues.

And the "involvement" works like this:

You can't have one -- without the other three.

So:

The Manly Man is Pious ; the Pious Man is Manly.

And Just -- Morally Ordered -- and Temperate.

The Morally Ordered Man is Manly ; the Manly Man is Morally Ordered.

And Pious -- and Self-Controlled.

For example :

I have a friend who has a co-worker who claims he used to be a Fighter.

And my friend therefore thinks of him as Manly.

But Plato -- and most of the other Greeks -- would NOT have agreed.

Because this alleged former fighter is NOT self-controlled -- anything but ;

he claims to be pious, but his actions do not remotely support his words ; and, of course,

he's not morally ordered -- his life is NOT a morally-ordered place.

Rather, it's an amoral, hedonistic, greedy, mess.

By Greek standards, then, of what we can call Integral or Involved Virtue, he's not manly.

He's not anything.

So, and once again :

Piety, Temperance, Moral Order, and Manhood, make up the Four Canonical or Integral Greek Virtues.

And the "integral" part works like this :

You can't have one -- without the other three.

So :

The Manly Man is Pious ; the Pious Man is Manly.

And Just -- Morally Ordered -- and Temperate.

The Morally Ordered Man is Manly ; the Manly Man is Morally Ordered.

And Pious -- and Self-Controlled.

And, you know, Fowler, the translator, doesn't have it quite right.

What Plato actually says is

And that's a very clear statement of what we might call Integral Virtue : Righteousness [Manly Moral Order] and Holiness [Manly Piety] in union with Thoughtfulness -- Manly Temperance.

What about Manliness aka Fighting Manhood?

Hang on for a moment.

Because in the Laws, Plato says that Wisdom and Temperance, when combined with Fighting Manhood -- yields perfect "Justice" -- that is, Perfect Order, a Manly and Moral Perfect Order :

Wisdom + Temperance + Fighting Manhood → Manly Moral Order -- Perfect Moral Order.

Again, Plato states that Wisdom and Temperance, when combined with Fighting Manhood -- yield perfect Moral Order.

And the reason Plato says that is because, as we'll see, in his view, a Wise and Temperate Manly Moral Order is dependent upon -- the Fighting Manhood -- of Men.

Now :

So far, in this particular passage from the Theaetetus, Plato hasn't mentioned Manliness per se.

Though we heard a lot about the Manliness of Theaetetus himself -- his Andreia -- both as a boy and a Man -- a Warrior -- at the beginning of the dialogue.

We saw that Theaetetus' conduct in battle was imbued with both kalon -- Manly Moral Beauty ; and agathon -- Manly Goodness -- both of which reduce, as you'll know if you've read Biblion Proton, to Fighting Manhood ;

And that as a youth, Theaetetus was characterized by his teacher, the geometrician Theodorus, as "brave [andreios -- that is, Manly] beyond any other."

And that, too, we discuss in In Union With Valour.

Because Valour too is Manhood.

Fighting Manhood.

And now, in the Theaetetus, and after much dialectic, Plato's about to speak of Fighting Manhood again -- and with a vengeance:

For Plato, through his spokesman Sokrates, goes on to say that

It is herein that the true cleverness [deinotes = terribleness -- "cleverness" here is highly perjorative] of a male is found and also his worthlessness [oudenia = worthlessness, nothingness] and cowardice [an-andria -- want of manhood, UN-manliness] ; for the knowledge of this is wisdom [sophia] or true [alethinos = true, real] virtue [areté -- Manhood, Manly Goodness, Manly Excellence], and ignorance [agnoia = want of perception, ignorance] of it is folly [a-mathia = stupidity, willful blindness] or manifest wickedness [kakia = wickedness, vice, cowardice, etc -- derives from kakke = human ordure] ; and all the other kinds of seeming cleverness and wisdom are paltry when they appear in public affairs and vulgar in the arts.

That's a really strong statement.

To put it mildly.

And by using the term an-andria -- want of Manhood, UN-manliness -- Plato goes unequivocally to the heart of the matter :

It's here that the superficiality of a male -- his worthlessness, his nothingness, his complete want of Manhood -- is found ; for the Knowledge of Righteousness, of Manly Moral Order, is Wisdom -- that is, True Manhood ; and ignorance of it is willful blindness and manifest and excremental wickedness ; and all the other kinds of seeming cleverness and wisdom are paltry when they appear in public affairs and vulgar in the arts.

Like I say, a strong and unequivocal statement.

And notice that Plato links worthlessness -- want of WORTH -- with want of MANHOOD.

Worth is Manhood ; Manhood is Worth.

And that is the Warrior and the Warriordom and the Warrior Kosmos within Plato -- speaking.

Again, Plato cannot escape the postulates of his own culture and its World of Being.

His fellow Athenians may wish to -- but he cannot and moreover will not.

Plato then continues :

Two patterns [paradeigma], my friend, are set up in the world, the divine [Godly, theios], which is most blessed [happy, fortunate], and the godless [atheos], which is most wretched. But these males do not see that this is the case, and their silliness and extreme foolishness blind them to the fact that through their unrighteous acts they are made like the one and unlike the other. They therefore pay the penalty for this by living a life that conforms to the pattern they resemble ; and if we tell them that, unless they depart from their "cleverness," the blessed place that is pure of all things evil will not receive them after death, and here on earth they will always live the life like themselves -- evil men associating with evil [kakoi kakois synontes = evil with evil joined] -- when they hear this, they will be so confident in their unscrupulous cleverness [terrible wickedness] that they will think our words the talk of fools.

So you can see that to be like God is to be Manly, to be possessed of Manhood, which man-ifests as Manly Righteousness, Manly Moral Order, and which includes Manly Self-Control ; while the worthless and wicked are characterized as exhibiting -- literally -- an-andria

-- UN-manliness, which Liddell and Scott define, and beautifully, as "want of manhood."

The Manly are blessed through full possession of their Manhood ; the UN-manly are wicked through want of manhood.

There are then, in this Platonic Warriordom informed by a Warrior Kosmos, two paradigms :

The Godly, which is, due to Manly Virtue, most happy and most fortunate ;

and the un-godly, which is, due to un-manly vice, most wretched.

And just as the word for UN-manly is an-andria -- want of Manhood -- so the word for UN-godly is a-theos -- want of God.

So:

The Manly are blessed, fortunate, and happy in their Manhood -- their Andreia ; the wicked are wretched through their an-andria -- their want of Manhood.

And a parallel is made between andreios -- Manliness ; and theios -- Godliness ;

and between an-andria -- UN-manliness ; and a-theotes -- UN-godliness.

That's presented with crystalline clarity in the Greek text ; you're free to disagree, but the words speak for themselves :

Manhood -- Fighting Manhood -- is Godliness.

Goodness.

And the Sum of All the Excellences of Man.

Now:

The idea of homoiosis Theo -- to be like to God, or, to be like to a God -- and since Greek lacks the indefinite articles "a" and "an," it's up to the translator, or the reader, if he reads Greek, to decide if Plato or anyone else means God -- or a God --

and please note in this regard that Plato was not a nascent Judeo-Christian monotheist -- he was a polytheist :

He frequently refers to "the Gods" -- hoi Theoi -- and says the most important human activity is to commune with those Gods :

And wise men tell us, Callicles, that Heaven and Earth and Gods and Men are held together by Communion and Friendship, by Orderliness, Temperance, and Justice ; and that is the reason, my friend, why they call the whole of this world by the name of Kosmos [order], not of disorder or dissoluteness. Now you, as it seems to me, do not give proper attention to this, for all your cleverness, but have failed to observe the great power of geometrical equality amongst both Gods and Men : you hold that self-advantage is what one ought to practice, because you neglect geometry.

~Plato. Gorg. 508a, translated by Lamb.

[O]f all rules this is the noblest [kalos] and truest [aletheia] -- that to engage in Sacrifice and Communion with the Gods continually, by prayers and offerings and devotions of every kind, is a thing most Noble [kalos] and Good [aristos] and helpful towards the happy life, and superlatively fitting also, for the Good [agathos] Man ; but for the wicked [kakos], the very opposite.

For the wicked man [ho kakos] is unclean [akathartos = uncleansed, unclean, impure ακαθαρτος]

of soul, whereas the Good Man [enantios = opposing, facing in fight εναντιος] is clean [katharos = clear of dirt, clean, spotless, unsoiled, clear, open, free, in moral sense, clear from shame or pollution, pure καθαρος] ;

and from him that is defiled [miaros = defiled, polluted, unclean μιαρος] no Good Man, nor God, can ever rightly receive gifts.

~Plato. Laws 4.716, translated by Bury.

He acted just as we now do in the case of sheep and herds of tame animals : we do not set oxen as rulers over oxen, or goats over goats, but we, who are of a nobler race, ourselves rule over them. In like manner the God, in his love for humanity, set over us at that time the nobler race of Daimonai who, with much comfort to themselves and much to us, took charge of us and furnished peace and modesty and orderliness and justice without stint, and thus made the tribes of men free from feud and happy.

And even today this tale has a truth to tell, namely, that wherever a State has a mortal, and no God, for ruler, there the people have no rest from ills and toils ; and it deems that we ought by every means to imitate the life of the age of Kronos, as tradition paints it, and order both our homes and our States in obedience to the immortal element within us, giving to reason's ordering the name of "law."[1] But if an individual man or an oligarchy or a democracy, possessed of a soul which strives after pleasures and lusts and seeks to surfeit itself therewith, having no continence and being the victim of a plague that is endless and insatiate of evil -- if such an one shall rule over a State or an individual by trampling on the laws, then there is no means of salvation.

[Footnote 1] A double word-play: nous [mind] νους = nomos [law] νομος, and dianoia [thought, intelligence] διανοια = daimonai [daimons]. Laws, being "the dispensation of reason," take the place of the "daimons" of the age of Kronos : the divine element in man (το δαιμονιον), which claims obedience, is reason (nous νους).

~Plato. Laws 4.713, translated by Bury

So -- Plato makes frequent reference to the GODS -- plural -- and the importance of Continual Communion, through prayer and sacrifice, with Them.

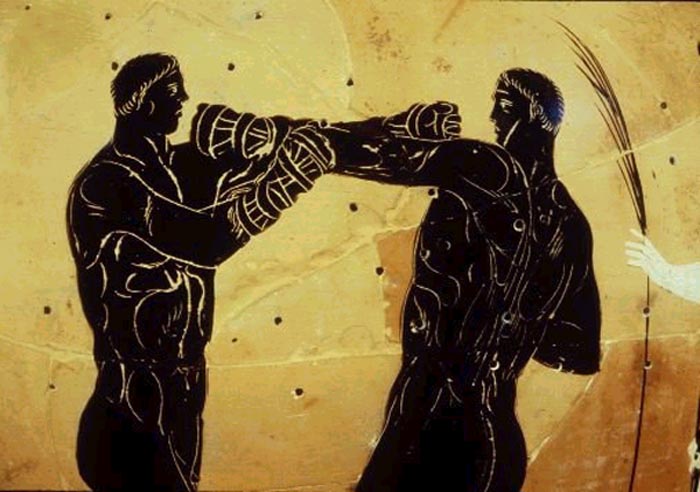

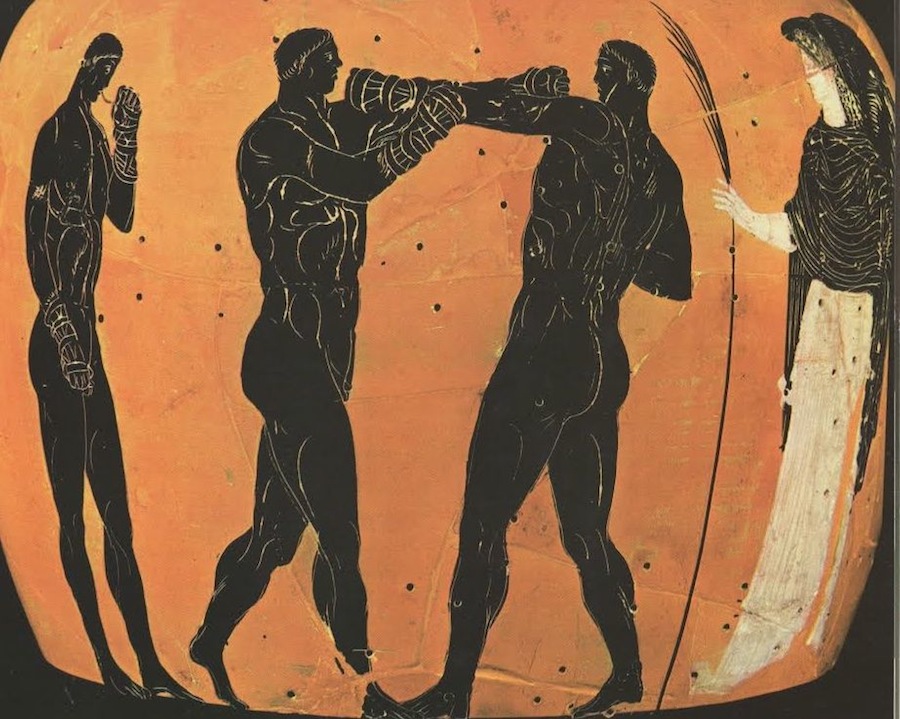

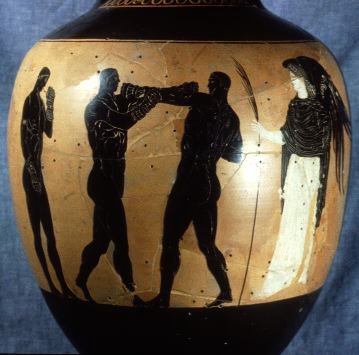

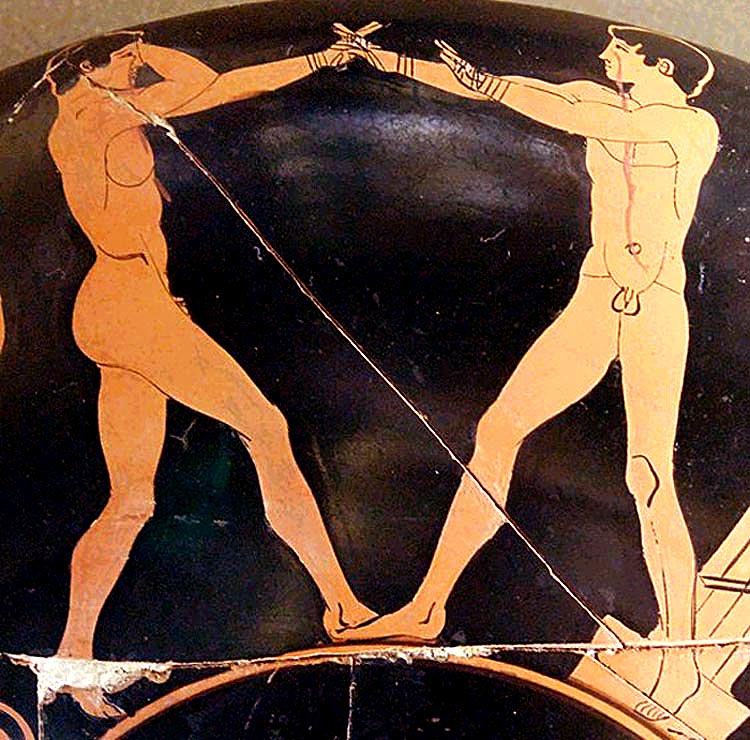

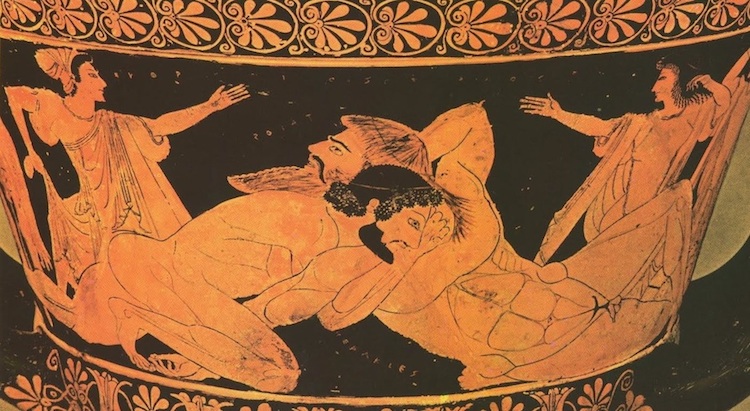

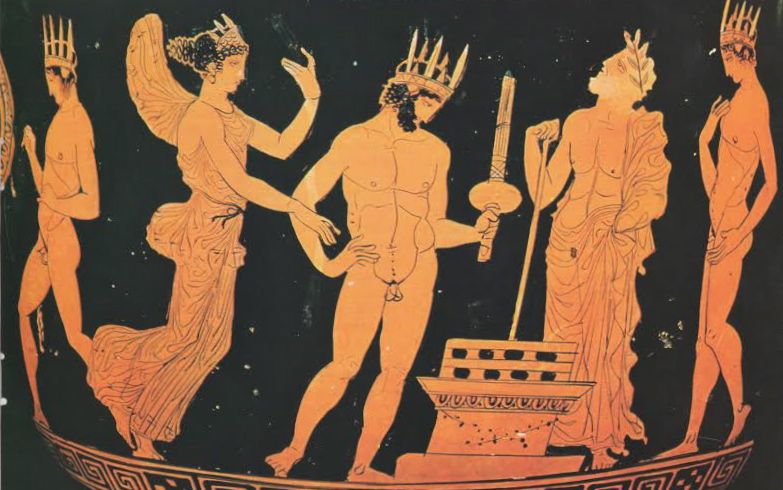

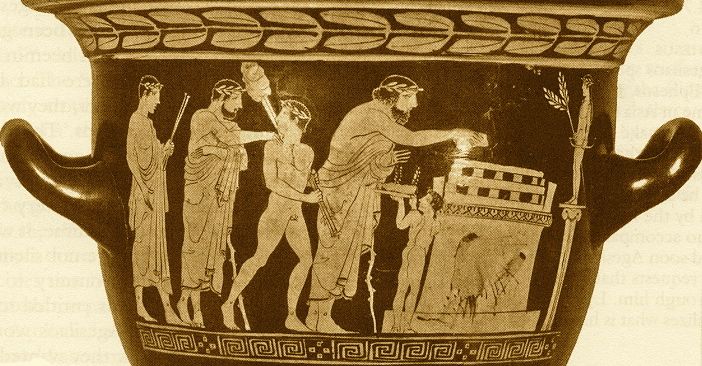

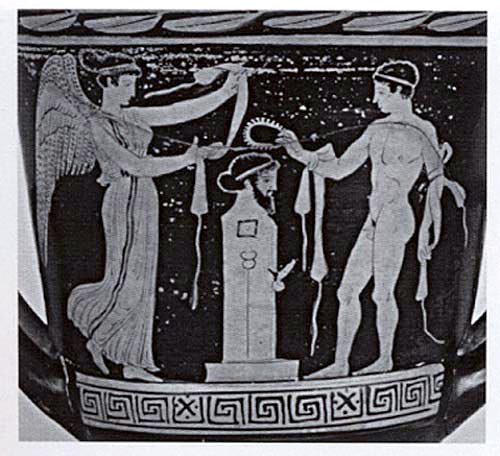

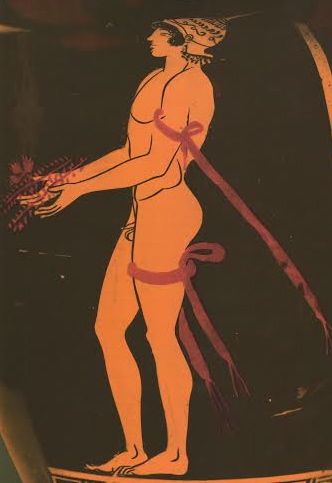

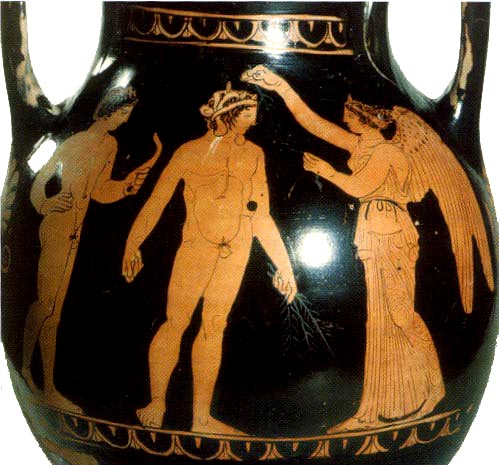

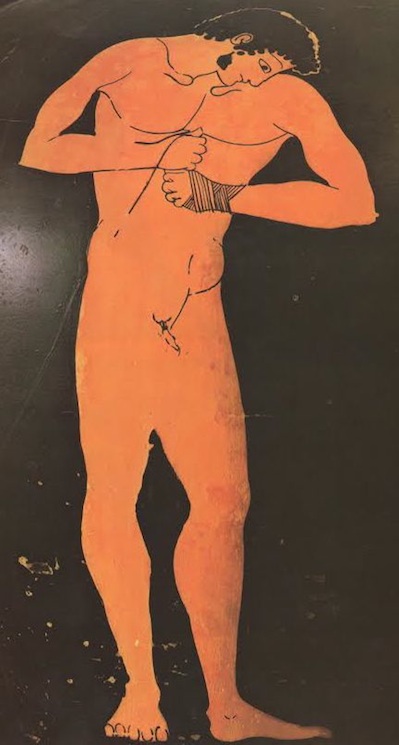

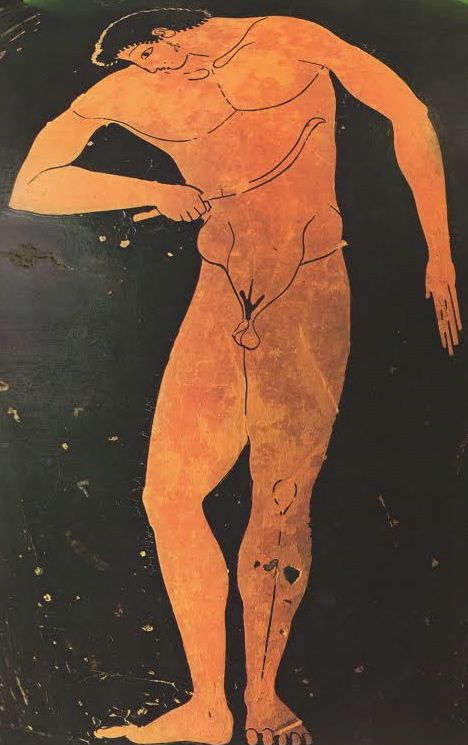

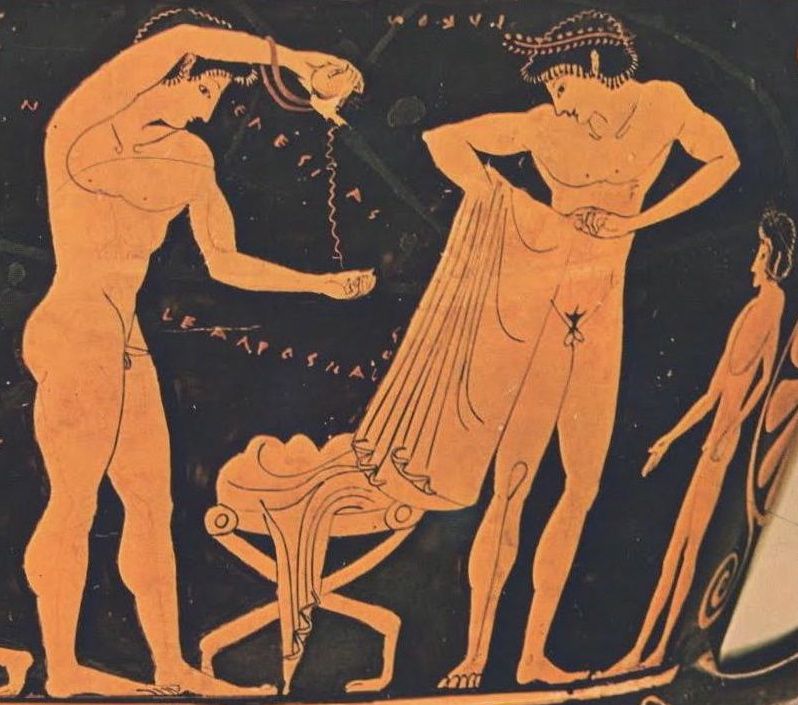

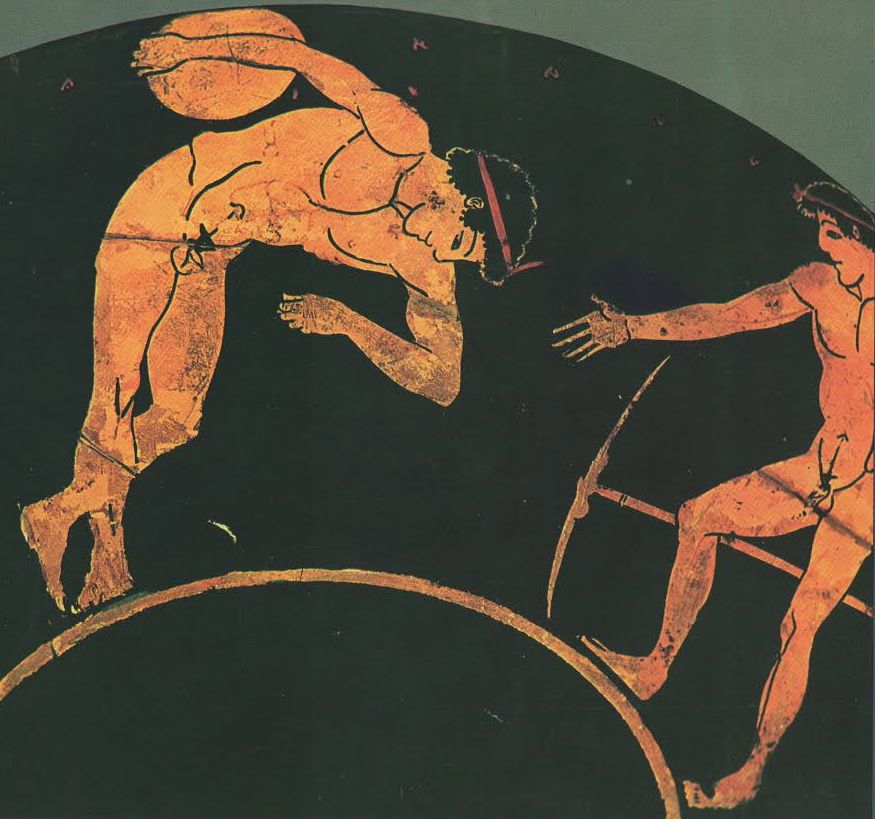

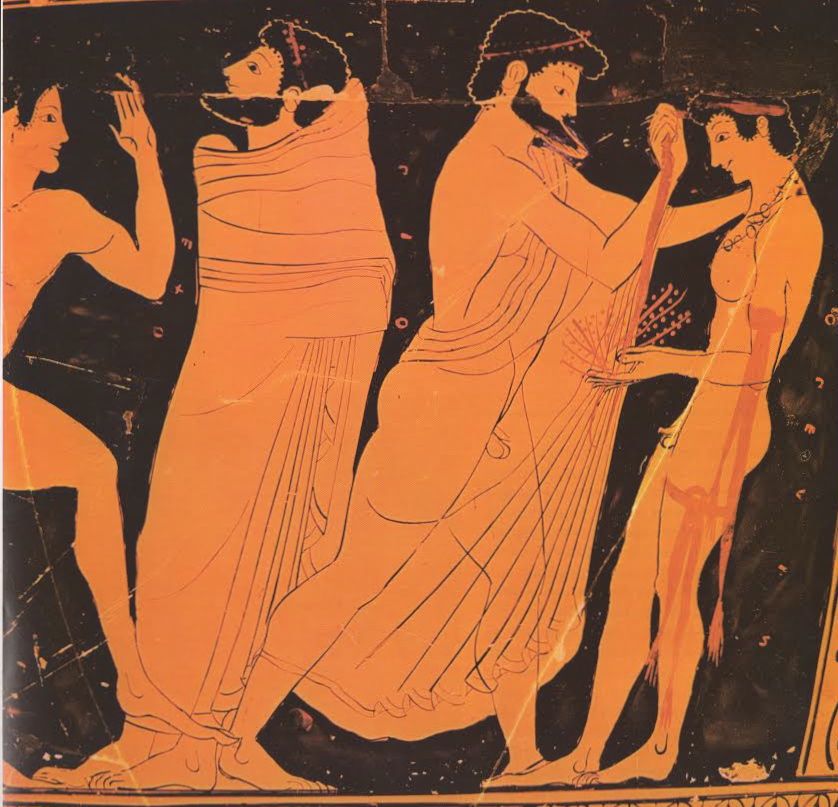

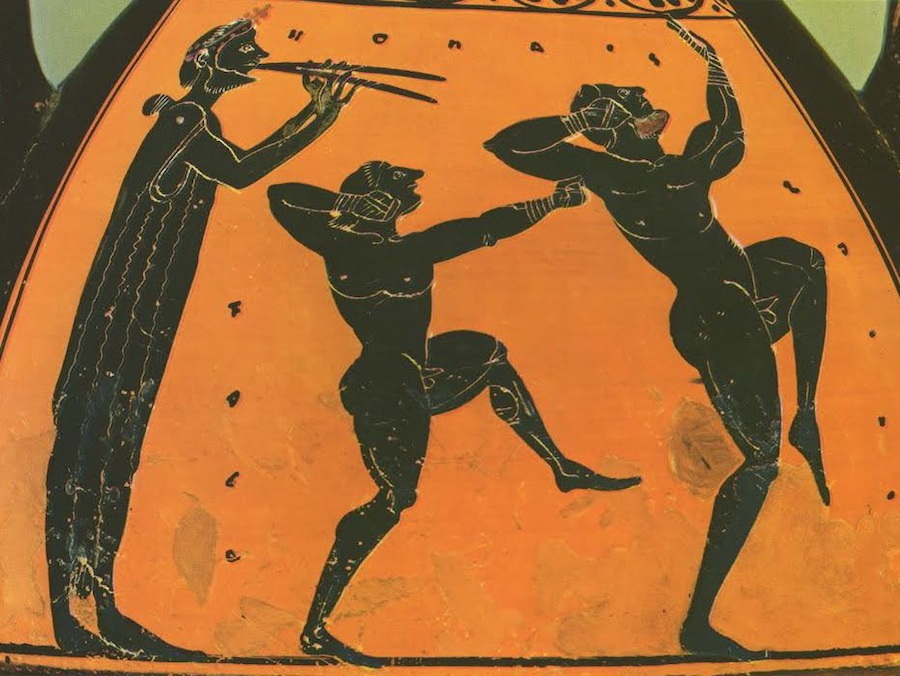

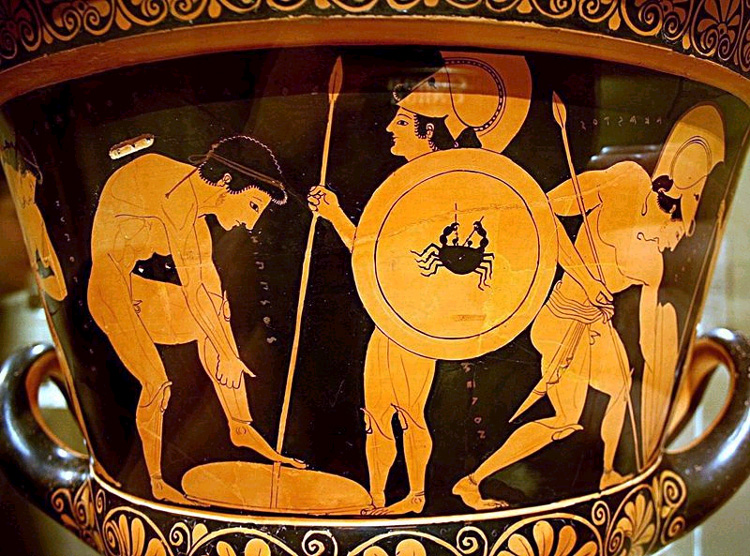

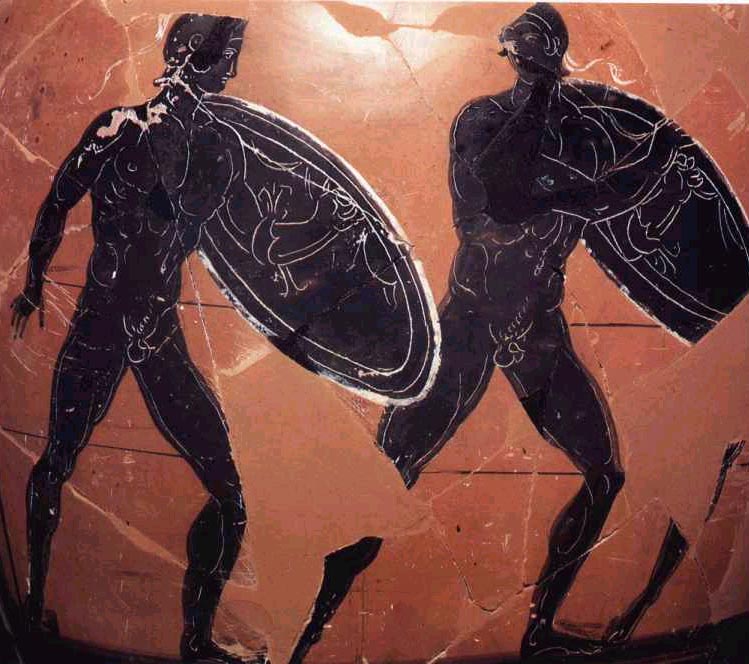

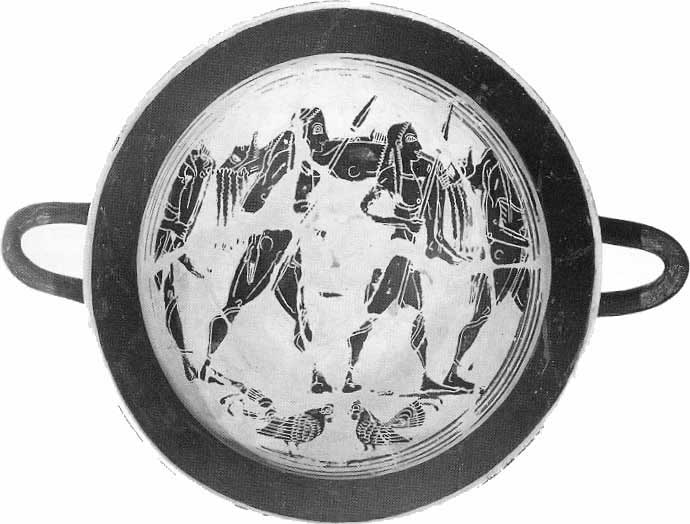

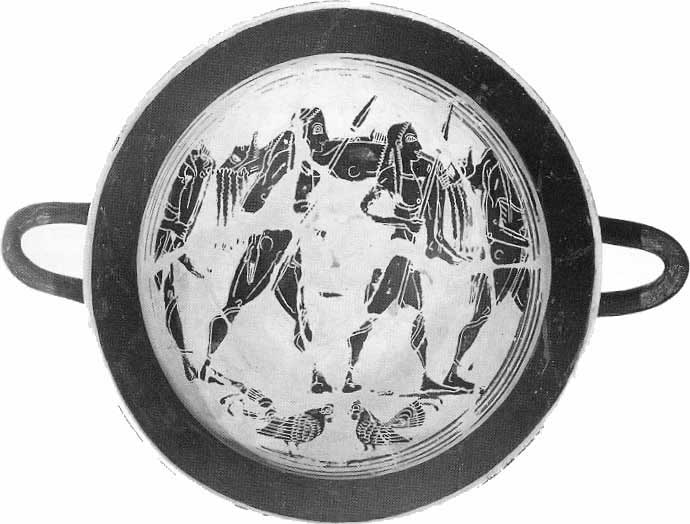

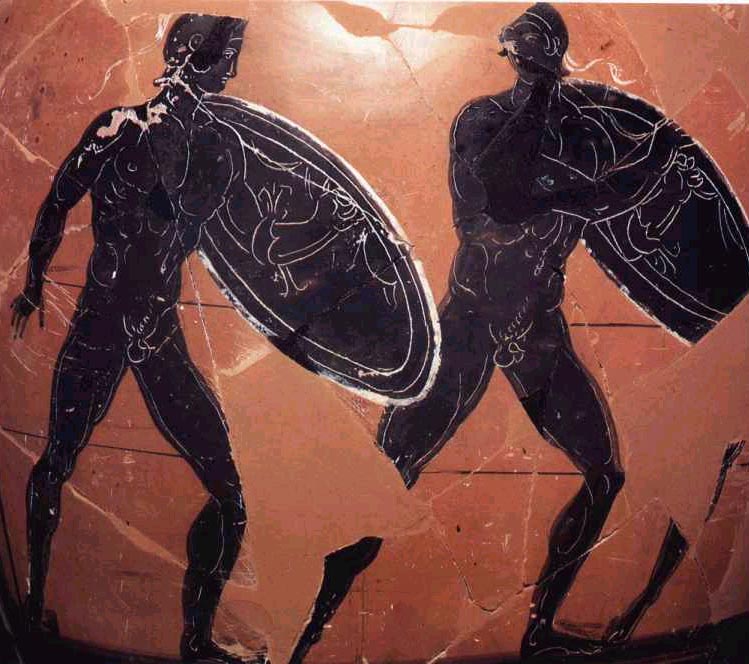

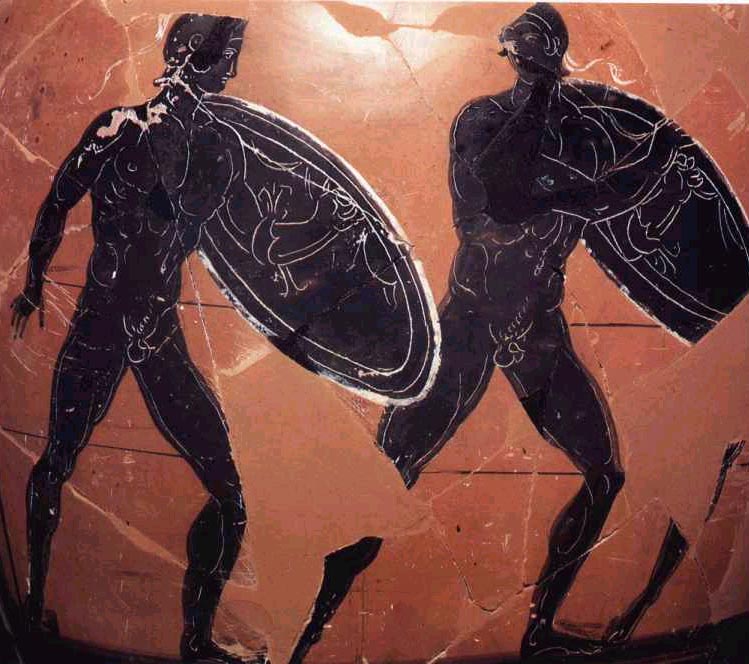

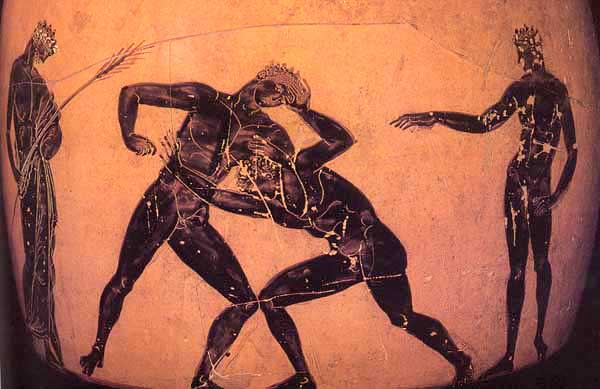

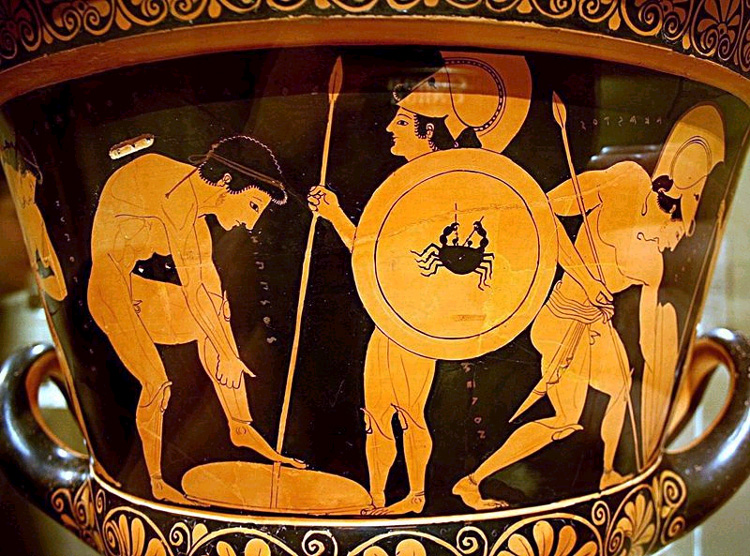

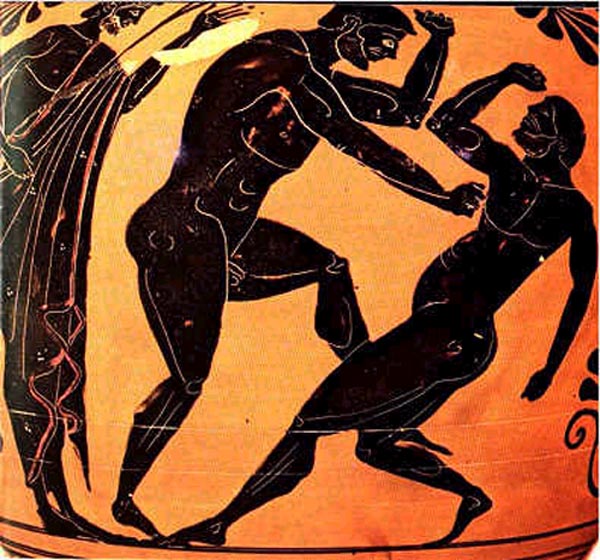

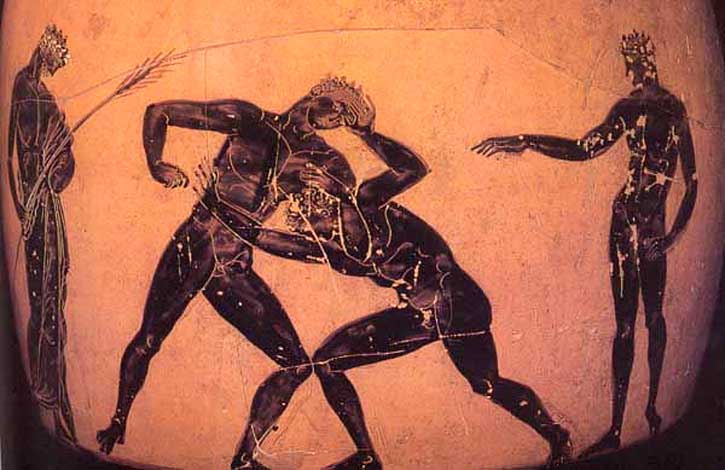

So -- Plato -- and the ceramic record -- makes frequent reference to the GODS -- plural -- and the importance of Continual Communion, through prayer and sacrifice, with Them.

And Plato says that the City-State -- like the individual -- must have a God -- or a God in the form of the Divine Element in Man, which is Reason -- for its ruler.

Again:

Plato says that the City-State -- like the individual -- must have a God -- not a mortal -- for its ruler.

So -- the GODS -- and the various individual Gods -- matter.

Each has His or Her own Temple, own rites, etc.

And Plato is very clear about that.

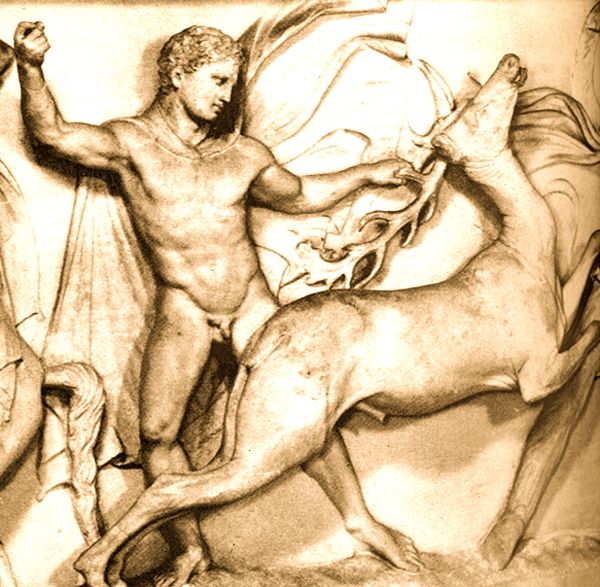

For example, he says, in the Laws, that in the city-state he's there proposing, a race in armor -- a hoplites dromos -- will be run to a Temple of Ares -- hieron Areos.

It's true that in the Timaeus, Plato hypothesizes a single creator God or Spirit -- the Demiurgos [Δημιουργος = the Craftsman, the Maker of the World ] -- who imposes Order, copied from the World of Being, upon the chaos of the world of becoming -- to the limited extent that that's possible, since there's always an intractable or incorrigible element in the world of becoming which defies ordering --

and that the Demiurgos then creates the other Gods, to whom He promises Immortality -- and whom He taxes with, among other things, designing human beings.

But just because those other Gods were secondarily created, doesn't mean They're unimportant, or, more to the point, not Gods ; the Demiurgos addresses Them with the intensively honorific Gods of Gods -- Θεοι Θεων -- making clear that They're Gods, Divine Beings, who, as Plato repeatedly makes plain, and as you've just seen, human beings must commune with -- continually.

It's also true that later interpreters of Plato -- particularly the intellectuals known as the Neo-Platonists, who lived many hundreds of years after Plato had died, and re-interpreted Plato to meet their own needs and purposes --

the Hellenist Neo-Platonists -- that is, the anti-Christian Neo-Platonists -- said that the Gods were Eternal -- that they could neither be created nor destroyed.

Thus obviating that passage in the Timaeus.

And they said that as part of their polemic against Christianity and the Christian Neo-Platonists.

Because, Yes, Virginia, there were Christian Neo-Platonists too.

By the third and fourth centuries AD, virtually all intellectuals were Neo-Platonists -- or in reaction to Neo-Platonism.

The fight between Christianity and what the non-Christians called Hellenism -- was a fight between two (or more) schools of Neo-Platonism.

Which had very little, if anything, to do -- and why mince words, it actually had nothing to do -- with a Jewish rabbi who may or may not have been crucified in Palestine sometime during the reign of Tiberius.

Be all that as it may -- for now --

The idea of homoiosis Theo -- to be like to God, or to a God -- occurs in a number of places in Plato, including in the concluding lines of Book II of the Republic, where Plato says the goal of

~Plat. Rep. 2.383C, translated by Shorey.

Again :

The Warrior-and-Governing Elite of the ideal Republic will be so educated as to be God-fearing and GOD-LIKE Men -- in so far as that's possible.

"To be like to God -- as far as may be"

"To be God-like Men -- as far as may be"

It's the same idea and the same goal -- for humanity and for Mankind.

And notice that these are Warriors who are to be God-like :

The goal of education in the Republic will be to produce Warriors who are "God-fearing [theosebes] Men and God-like [theios] -- in so far as that is possible for humanity."

The Warriors will be God-fearing and God-like Men.

Manliness is Godliness ; Godliness is Manliness.

Indeed, that educational goal is so important to Plato -- that paidei-ic goal of raising the young Warriors to be not just God-fearing but God-like Men --

that he devotes much of Books II and III of the Republic to setting forth, and demonstrating, through dialectic, just what God and the Gods are like --

and why, therefore, much of the poetry of Homer and Hesiod et alia, the glorious heritage of the Greek people, needs, for educational purposes at least, to be expurgated, re-written, and/or censored.

That's a shocking idea to us today, who think of poetry and art in general as sacred --

But so did Plato, himself a poet, who says unabashedly in Book X of the Republic that "a certain love and reverence for Homer has possessed me from boyhood" ; and then adds, "Yet all the same we must not honor a man above truth."

And, in point of fact, many Greek intellectuals of the fourth century BC thought as Plato did.

Why?

Because in Homer, in particular, the Gods are depicted, often, as both very powerful and very petty -- they get into arguments with each other, they play dirty tricks on each other, etc -- and worst of all, from Plato's point of view, they do things which are to the detriment of Humanity.

That, to Plato -- and remembering that he was a philosopher -- was logically simply not possible.

God -- and the Gods -- are Good -- and They never, therefore, harm human beings.

They are Beneficent Beings whose actions are always attuned to and augment the Well-Being of Men and of Mankind.

The argument that Plato makes in that regard is very important.

It's sometimes dismissed as being of little interest to the people of our modern and oh-so-enlightened world.

That's not true.

Plato's argument, and in particular his dialectic, his reasoning-through of the Why of this matter -- is both very important and highly germane to Men like ourselves.

And for that reason, we're going to look at it, and analyze what it says.

We'll start with Book II of the Republic.

The expositor is Sokrates, his concern, once again, is with the education of the Warrior-Ruler Elite -- the Guardians -- in the Republic -- and he's discussing that education with Adeimantus, one of Plato's brothers :

Sokrates

"Yes, that is reasonable," Adeimantus said; "but if again someone should ask us to be specific and say what these compositions may be and what are the tales, what could we name?"

And I replied, "Adeimantus, we are not poets, you and I at present, but founders of a state. And to founders it pertains to know the patterns on which poets must compose their fables and from which their poems must not be allowed to deviate; but the founders are not required themselves to compose fables."

"Right," he said; "but this very thing -- the patterns or norms of right speech about the Gods, what would they be?"

"Something like this," I said. "The true quality of God we must always surely attribute to Him whether we compose in epic, melic, or tragic verse."

"We must."

"And is not God of course good [agathos] in reality and always to be spoken of as such?"

"Certainly."

"But further, no good thing is harmful, is it?"

"I think not."

"Can what is not harmful harm?"

"By no means."

"Can that which does not harm do any evil [kakos]?"

"Not that either."

"But that which does no evil would not be cause of any evil either?"

"How could it?"

"Once more, is the good [to agathon -- the Supreme Good] beneficent [ophelimos]?"

"Yes."

"It is the cause, then, of welfare [eupragia -- well-being]?"

"Yes."

"Then the good [to agathon -- the Supreme Good] is not the cause [aitia] of all things, but of things that are well [eu] it's the cause -- of things that are ill [kakos] it is blameless."

"Entirely so," he said.

"Neither, then, could God," said I, "since he is good, be, as the multitude say, the cause of all things, but for mankind he is the cause of few things, but of many things not the cause. For good things are far fewer with us than evil, and for the good we must assume no other cause than God, but the cause of evil we must look for in other things and not in God."

"What you say seems to me most true," he replied.

"Then," said I, "we must not accept from Homer or any other poet the folly of such error as this about the Gods when he says

and to whomsoever Zeus gives of both commingled --

but the man for whom he does not blend the lots, but to whom he gives unmixed evil --

nor will we tolerate the saying that 'Zeus is dispenser alike of good and of evil to mortals.'

"But as to the violation of the oaths and the truce by Pandarus, if anyone affirms it to have been brought about by the action of Athena and Zeus, we will not approve, nor that the strife and contention of the Gods was the doing of Themis and Zeus; nor again must we permit our youth to hear what Aeschylus says --

A God implants the guilty cause in men

but if any poets compose a 'Sorrows of Niobe,' the poem that contains these iambics, or a tale of the Pelopidae or of Troy, or anything else of the kind, we must either forbid them to say that these woes are the work of God, or they must devise some such interpretation as we now require, and must declare that what God did was righteous [dikaios] and good [agathos], and they were benefited by their chastisement. [Shorey: "Plato's doctrine that punishment is remedial must apply to punishments inflicted by the Gods. . . . Yet there are some incurables."] But that they were miserable who paid the penalty, and that the doer of this was God, is a thing that the poet must not be suffered to say ; if on the other hand he should say that for needing chastisement the wicked [hoi kakoi] were miserable and that in paying the penalty they were benefited by God, that we must allow. But as to saying that God, who is good, becomes the cause of evil [kakon de aition] to anyone, we must contend in every way that neither should anyone assert this in his own city if it is to be well governed, nor anyone hear it, neither younger nor older, neither telling a story in meter or without meter ; for neither would the saying of such things, if they are said, be holy [hosios], nor would they be profitable to us or concordant with [symphonos] themselves."

"I cast my vote with yours for this law," he said, "and am well pleased with it."

"This, then," said I, "will be one of the laws and patterns concerning the Gods to which speakers and poets will be required to conform, that God is not the cause of all things, but only of the good."

"And an entirely satisfactory one," he said.

Bill Weintraub:

So, first off, God -- and the Gods -- are Good, and they cannot therefore be the authors of bad events or human suffering, etc. -- The Gods' actions towards human beings are always beneficial and always enhance the well-being, the welfare, of humanity :

And notice please that "The Good" -- which is really the Idea of Good -- and God -- are two different entities.

To you, as to the Neo-Platonists, they may appear identical -- but they aren't to Plato.

They're two distinct entities.

And that matters not least because of the functional definition of the Idea of Good --

Once again, for Plato, God and that Good Purpose -- are two distinct entities.

But, you may say, if "The Good [to agathon -- the Supreme Good] is not the cause of all things, but of things that are well it's the cause" ; and if "God is not the cause of all things, but only of the Good" -- doesn't it appear they'd have to be identical -- or at least virtually identical?

Yes, it does, but for ontological reasons, and for now, at least, you need to understand that to Plato, they're not.

And that's because Plato is Plato, and he's just smart enough to figure out that if, as the Neo-Platonists did, you make them identical, things become, philosophically speaking, very messy -- and in very short order too.

So, and that said :

What you need to be clear about for now is that --

God, the Gods, and the Good -- are themselves good and the cause of all that's well and good ; They're capable only of acts of well-being and beneficence ; and to humanity in particular, They do no harm.

Plato then attacks the notion of God and the Gods as shape-shifters and wizards :

Sokrates

"I cannot say offhand," he replied.

"But what of this: If anything went out from its own form, would it not be displaced and changed, either by itself or by something else?"

"Necessarily."

"Is it not true that to be altered and moved by something else happens least to things that are in the best condition, as, for example, a body by food and drink and toil, and plants by the heat of the sun and winds and similar influences -- is it not true that the healthiest and strongest is least altered?"

"Certainly."

"And is it not the soul that is bravest [andreios = Manly, andreiotatos = most Manly] and most intelligent [phronimos = wise, sensible, phronimotatos = wisest, most sensible], that would be least disturbed and altered by any external affection [pathos -- a complex word -- Shorey translates it as "affection," Jowett, as "incident," but what Plato means is clear enough -- pathos here is anything external to the Self -- be it an incident or accident or calamity or passion or emotion -- and Plato's rheorical question to Adeimantus is -- Will not the Soul -- or God -- which is Most Manly and Most Wise -- be least disturbed and altered by any such external event]?

"Yes."

Bill Weintraub:

So :

Plato is here saying that the Soul -- the God -- which is Most Manly and Most Wise -- and in later chapters we'll hear a Spartan king talk of being Warlike and Wise -- the God which is Most Manly and Most Wise -- would be least disturbed and altered by any external "affection" -- pathos -- and as you can see from the definitions of pathos, these are world of becoming incidents, accidents, sufferings, misfortunes, etc.

Clearly, a God is not subject to such incidents, accidents, etc.

Because, basically, the Gods are outside and independent of the world of becoming -- like the entities in the World of Being, they're immortal and immutable.

Plato:

"And, again, it is surely true of all composite implements, edifices, and habiliments, by parity of reasoning, that those which are well made and in good condition are least liable to be changed by time and other influences."

"That is so."

"It is universally true, then, that that which is in the best state by nature or art or both admits least alteration by something else."

"So it seems."

"But God, surely, and everything that belongs to God is in every way in the best [aristos -- best, Most Manly] possible state."

"Of course."

"From this point of view, then, it would be least of all likely that there would be many forms in God."

"Least indeed."

"But would he transform and alter himself?"

"Obviously," he said, "if he is altered."

"Then does he change himself for the better and to something fairer [kalos], or for the worse and to something uglier than himself?"

"It must necessarily," said he, "be for the worse if he is changed. For we surely will not say that God is deficient in either beauty [kalon -- Moral Beauty] or excellence [areté -- Manly Goodness]."

"Most rightly [orthotatos] spoken," said I.

"And if that were his condition, do you think, Adeimantus, that any one God or Man would of his own will worsen himself in any way?"

"Impossible," he replied.

"It is impossible then," said I, "even for a God to wish to alter himself, but, as it appears, each of them being the fairest and best [kalos kai aristos -- Most Noble and Most Manly] possible abides for ever simply in his own form."

"An absolutely necessary conclusion to my thinking."

"No poet then," I said, "my good friend, must be allowed to tell us that

Nor must anyone tell falsehoods about Proteus and Thetis, nor in any tragedy or in other poems bring in Hera disguised as a priestess collecting alms 'for the life-giving sons of Inachus, the Argive stream.'

And many similar falsehoods they must not tell. Nor again must mothers under the influence of such poets terrify their children with harmful tales, how that there are certain Gods whose apparitions haunt the night in the likeness of many strangers from all manner of lands, lest while they speak evil of the Gods they at the same time make cowards of children."

"They must not," he said.

Bill Weintraub:

Why does this matter?

Plato:

"But," said I, "may we suppose that while the Gods themselves are incapable of change they cause us to fancy that they appear in many shapes deceiving and practising magic upon us?"

"Perhaps," said he.

"Consider, would a God wish to deceive, or lie, by presenting in either word or action what is only appearance?"

"I don't know," said he.

"Don't you know," said I, "that the veritable lie, if the expression is permissible, is a thing that all

Gods and Men abhor?"

"What do you mean?" he said.

"This," said I, "that falsehood in the most vital part of themselves, and about their most vital concerns, is something that no one willingly accepts, but it is there above all that everyone fears it."

"I don't understand yet either."

"That is because you suspect me of some grand meaning," I said; "but what I mean is, that deception in the soul about realities, to have been deceived and to be blindly ignorant and to have and hold the falsehood there, is what all men would least of all accept, and it is in that case that they loathe it most of all."

"Quite so," he said.

"But surely it would be most wholly right, as I was just now saying, to describe this as in very truth falsehood -- ignorance namely in the soul of the man deceived. For the falsehood in words is a copy of the affection [pathema παθημα = anything that befals one, a suffering, calamity, misfortune ; a passive emotion or condition ; in pl incidents, occurences] in the soul, an after-rising image of it and not an altogether unmixed falsehood. Is not that so?"

"By all means."

"Essential falsehood, then, is hated not only by Gods but by Men."

"I agree."

"But what of the falsehood in words, when and for whom is it serviceable so as not to merit abhorrence? Will it not be against enemies? And when any of those whom we call friends owing to madness or folly attempts to do some wrong, does it not then become useful to avert the evil -- as a medicine? And also in the fables of which we were just now speaking owing to our ignorance of the truth about antiquity, we liken the false to the true as far as we may and so make it edifying."

"We most certainly do," he said.

"Tell me, then, on which of these grounds falsehood would be serviceable to God. Would he because of his ignorance of antiquity make false likenesses of it?"

"An absurd supposition, that," he said.

"Then there is no lying poet in God."

"I think not."

"Well then, would it be through fear of his enemies that he would lie?"

"Far from it."

"Would it be because of the folly or madness of his friends?"

"Nay, no fool or madman is a friend of God."

"Then there is no motive for God to deceive."

"None."

"From every point of view the divine and the divinity are free from falsehood."

"By all means."

"Then God is altogether simple and true in deed and word, and neither changes himself nor deceives others by visions or words or the sending of signs in waking or in dreams."

"I myself think so," he said, "when I hear you say it."

"You concur then," I said, "this as our second norm or canon for speech and poetry about the Gods -- that they are neither wizards in shape-shifting nor do they mislead us by falsehoods in words or deed?"

"I concur."

"Then, though there are many other things that we praise in Homer, this we will not applaud, the sending of the dream by Zeus to Agamemnon, nor shall we approve of Aeschylus when his Thetis avers that Apollo singing at her wedding,

Their days prolonged, from pain and sickness free,

"When anyone says that sort of thing about the Gods, we shall be wroth with him, we will refuse him a chorus, neither will we allow teachers to use him for the education [paideia] of the young [hoi veoi] if our

Guardians [phulax -- Warriors] are to be God-fearing [theosebes] Men and God-like [theios] in so far as that is possible for humanity."

"By all means," he said, "I accept these norms and would use them as canons and laws."

~Plat. Rep. 2.379a - 383C, translated by Shorey.

Bill Weintraub:

Again, what we see here is a view common to many fourth-century BC intellectuals, that the Iliad, and Homer and the other poets, as wonderful as their work may be -- must be expurgated -- censored, we would say -- if they are to be fit educators for the young.

For, says Plato -- Boys, Youth, and Young Men must be taught the plain truth :

So -- "our Warriors are to be God-fearing Men and God-like -- in so far as that is possible for humanity," says Plato --

And we're back to the Theaetetus and Plato's homoiosis theo -- "to be like to God -- as far as may"

So -- Plato's goal, from at least the Republic forward is homoiosis theo -- that Men "be like to God, be God-like, so far as that's possible" --

And for that to occur, says Plato in Books II and III of the Republic, the old Greek myths, as charming and poetic as they are, must be reformed.

Re-written.

Expurgated.

For, unlike the way the Gods are depicted in Homer and other poets :

The Gods are profoundly Moral -- that is to say, Good.

They hate falsehood and lies.

They Love Manliness.

And for hoi neoi -- the youth -- to become, to grow up to be, Manly Men, Warriors -- they must be told, as boys, those Truths -- and, the Truth about Death as well -- that Death is nothing to fear, for the afterlife, too, is not to be feared, but is worthy of praise.

So -- in setting out his educational reforms, Plato, in the Republic, also presents his reformed view of the Gods -- again, a view common among the intellectuals of his day --

That the Gods are Godly -- we would say "good" -- that They hate falsehood and lies and deceit, and are simple and true in word and deed -- and that They love Manliness, and that for a Man and a Warrior, the noblest goal, therefore, is to be a "God-fearing Man [theosebes] and God-like [theios] -- in so far as that is possible for humanity."

And that's why Plato's view of Ares, as presented in the Cratylus, is not of some fiend-like destroyer spirit insatiate of blood --

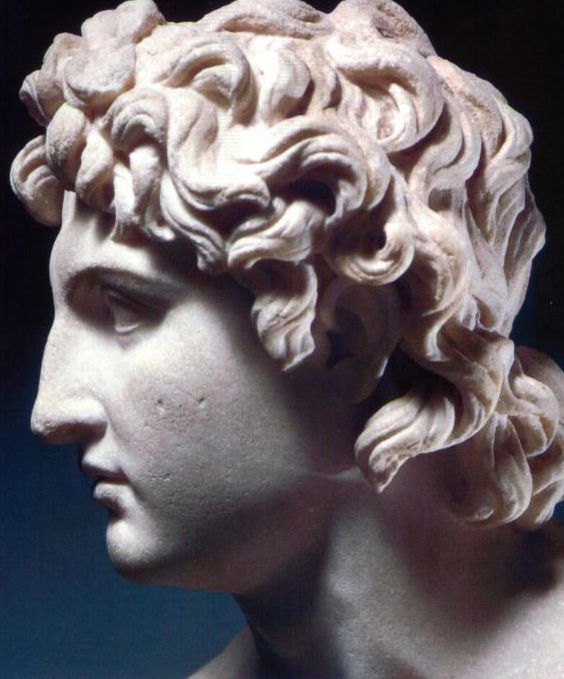

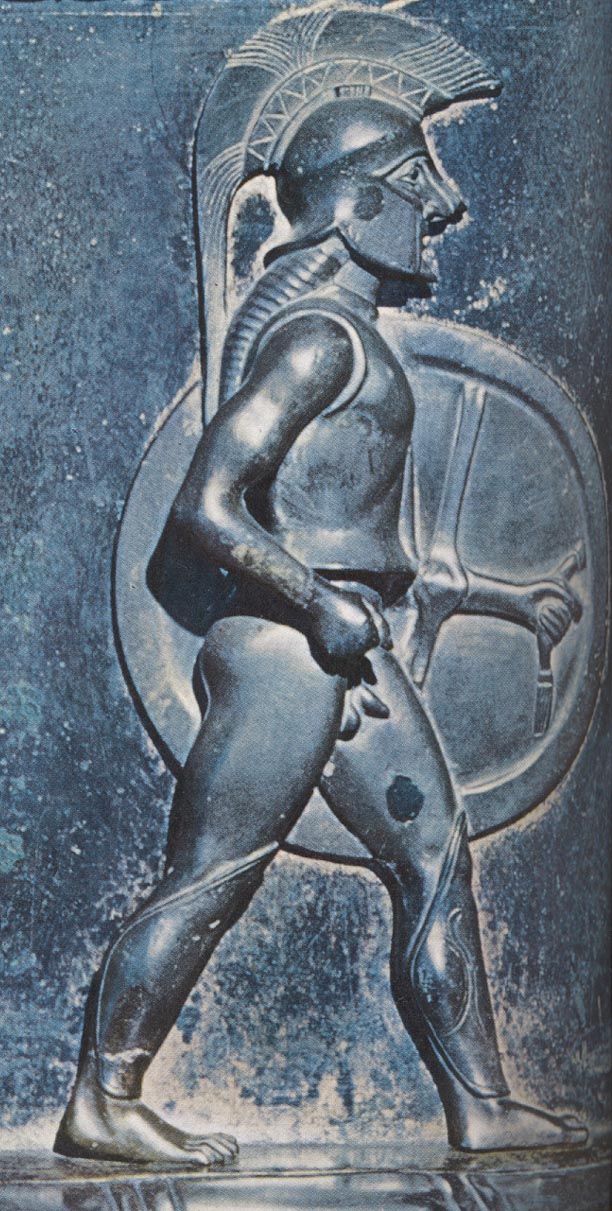

but of a God who's Virile because He's possessed of Fighting Manhood and the requisite Hardness to express that Fighting Manhood:

So :

In his magesterial What Plato Said, famed Platonist Paul Shorey offers this precis of Plato's view of the Gods :

Such tales as Homer and Hesiod tell about the Gods must never be told to [the] alumni [of our Republic's Warrior training program], says Sokrates ; and in pursuance of his criticism he lays down three canons of sound theology :

That view of the Gods -- Plato's view of the Gods -- asserted ca 380 BC -- is the one that subsequently prevailed in the ancient world -- as we can see from this excerpt from the Neo-Platonist and Hellenist Sallustius' fourth-century AD book, Concerning the Gods and the Universe, written more than 700 years after the Republic :

These considerations decide the problem of worship. The Gods need nothing ; the honours we pay them are for our own benefit. Their providence extends everywhere, and all who are fit may enjoy it.

Fitness is obtained by imitation, and imitation is the basis of all cult : the shrines correspond to the sky, the altars to the earth, the images to life (that is why they are made in the likeness of living beings), prayers to the intellectual element, the magic vowels to the unspeakable powers of the sky, plants and stones to matter, and the animals sacrificed to the unreasonable life in us. From all this the Gods gain no benefit, but we gain union with them.

~Sallustius, Concerning the Gods and the Universe, translated and epitomized by Arthur Darby Nock.

Now -- what does all this have to do with Lord Ares?

A lot.

Because, if you click on the link for Liddell and Scott's definition of Ares, you get "god of war and slaughter, strife and pestilence, destruction"

To Plato, that's not acceptable, and more to the point, cannot logically be true, since God and the Gods are always Good and Beneficent ; They don't deceive or lie ; They're deficient neither in Moral Beauty nor in Manly Goodness.

For that reason, a God couldn't possibly wish to bring about mass slaughter, pestilence, and destruction -- at least not destruction which is harmful to the Good.

Those are evils -- and says Plato, in the Theaetetus,

So :

Evils cannot be done away with ;

but neither can they have their place among the Gods.

Rather, they hover about mortal nature and this earth -- the world of becoming.

Which means that Liddell and Scott's definition, while it may be "true" of a character in Homer's poem, is not true to the Gods, to the Divine, to the very structure, the moral structure, of the Kosmos.

And, as Plato says, "We must not honor a man -- above Truth."

Who, then, and Truly, is Ares?

As I said, Plato tells us, quite clearly, in the Cratylus :

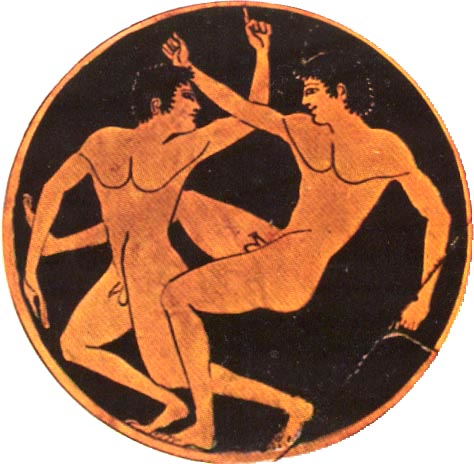

Ares is the God of Fighting Manhood.

And Fighting Manhood is beneficent -- and necessary -- in a world of becoming whose denizens are far from perfect :

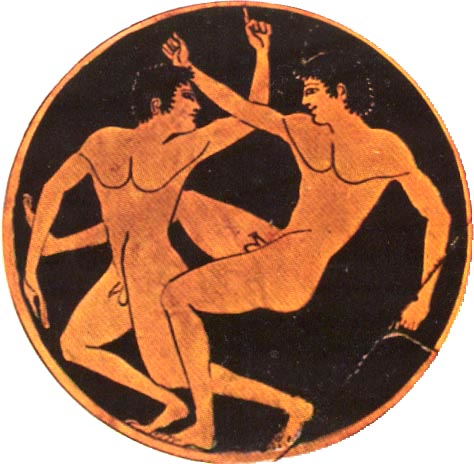

Every man ought to be at once passionate [thumoeides : high-spirited, courageous] and gentle in the highest degree. For, on the one hand, it is impossible to escape from other males' wrongdoings, when they are cruel and hard to remedy, or even wholly irremediable, otherwise than by victorious [nikao] fighting [machomai] and self-defence [amuno], and by punishing most rigorously ; and this no soul can achieve without noble passion [thumos gennaios].

We'll be discussing this quote from Plato and his Laws at length in the next chapter of Biblion Pempton.

But what you can hear Plato saying quite clearly in the Theaetetus is that

And that in turn takes us back to Liddell and Scott's somewhat schizoid definition of Ares, for in it they also say

The Root ΑΡ [ΑΡΗΣ], appears also in αρετη, the first notion of goodness (virtus) being that of manhood, bravery in war.

Ares, then, far from being a force for ill, is the Divine Source of the First Notion of Goodness (Virtus) -- which is Manhood, FIGHTING Manhood.

Fighting Manhood : "the First Notion of Goodness (Virtus)," say Liddell and Scott.

And what is Virtus?

We're going to look at Virtus in depth in Chapter V of Biblion Pempton, but we can here note that in 1890, Lewis defined Virtus as

Ares is the God of Fight, Ares is the God of Manhood, Ares is the God of Fighting Manhood.

And Ares is the God therefore of Goodness, the Manly Goodness of Andreia and Areté and Virtus -- and all that's apprehended therein :

And those are boons to Mankind, they're beneficent, they contribute to and make possible the well-being of humanity and the flourishing of Men -- in the chaotic environment of the world of becoming.

And in the succeeding chapters of Biblion Pempton, we'll see just how a Warrior Culture and a Warrior Kosmos ruled by Lord Ares and informed by the Divine Gift of Fighting Manhood -- functions to benefit, celebrate, and exalt -- the Lives of Men.

Because :

Manhood -- Fighting Manhood -- is Godliness.

Goodness.

And the Sum of All the Excellences of Man.

Which is why -- to be possessed of Fighting Manhood --

Is to be like to -- a God.

~Liddell and Scott. An Intermediate Greek-English Lexicon. Bill Weintraub

BIBLION PEMPTON

ARES : High-Minded Passion and Noble Anger

By Bill Weintraub

Let's begin by returning, for a moment, to Plato and the Theaetetus :

It's here that the superficiality of a male -- his worthlessness, his nothingness, his complete want of Manhood -- is found ; for the Knowledge of Righteousness, of Manly Moral Order, is Wisdom -- that is, True Manhood ; and ignorance of it is willful blindness and manifest and excremental wickedness ; and all the other kinds of seeming cleverness and wisdom are paltry when they appear in public affairs and vulgar in the arts.

Question :

Where before have we seen Plato make such a strong condemnation of an-andria -- want of manhood, UN-manliness -- and link it with evil and that which is un-Godly?

While saying that Manhood -- Fighting Manhood -- is essential to Virtue -- and thus Godliness?

Answer :

It was in the Menexenus, which we discussed in Biblion Tetarton, in the section titled In Union With Valour.

Second Question :

Is it common for Plato to say one thing in one dialogue -- and then what is essentially the same thing -- in another?

Answer :

YES.

And this is a very important point.

In The Unity of Plato's Thought, published in 1903, Paul Shorey demonstrated, quite conclusively, that Plato, unlike those thinkers whose opinions change over the years, was extremely consistent in what he said and therefore believed for a period of about fifty years -- that is, from about the age of thirty, when he first, we think, "published" -- to the age of eighty -- when he died.

Which means that if Plato says something once -- chances are he'll say it again.

His emphasis and focus change from dialogue to dialogue -- as we discussed in Biblion Tetarton.

BUT HIS ESSENTIAL BELIEFS DO NOT.

And what he thinks about Manliness -- Fighting Manhood -- and its opposite -- UN-manliness -- does not change, and it is this :

Men who lack Manhood -- Fighting Manhood -- are worthless ; and that worthlessness poisons the society in which they live :

It's here that the superficiality of a male -- his worthlessness, his nothingness, his complete want of Manhood -- is found ; for the Knowledge of Righteousness, of Manly Moral Order, is Wisdom -- that is, True Manhood ; and ignorance of it is willful blindness and manifest and excremental wickedness ; and all the other kinds of seeming cleverness and wisdom are paltry when they appear in public affairs and vulgar in the arts.

Now :

Why does Plato believe what he believes and say what he says?

Because --

and this is not to take anything away from Plato, which can't be done in any case because he was and remains the World's greatest and most humane Thinker --

But Plato believes what he believes and says what he says because he's a Warrior, living in a Warriordom, which is informed by a Warrior World of Being -- a Warrior Kosmos.

And that too takes nothing away from Plato because what it says is that Plato had the Wisdom, the great and overwhelming Wisdom, to accept and to promulgate -- that Warrior Wisdom, that great and overwhelming Warrior Wisdom -- of his Warriordom and his Warrior World of Being.

So :

As we discussed in Biblion Tetarton, and as Shorey and Jaeger make clear, to Plato the world -- the Kosmos -- is and must be -- a morally-ordered place.

And it is so-ordered by God and the Gods.

And what I'm saying in this Lexicon is that to Plato -- Manhood, Manliness, Manly Spirit -- Fighting Manhood -- is Integral to that Godly Moral Order, which is a Manly Moral Order.

Again :

To Plato, Fighting Manhood is Integral to the Godly, Manly, Moral Order -- of the Kosmos.

As it was to the Greeks who preceded him -- and to the Greco-Roman world, as we'll see, which succeeded him.

Fighting Manhood is Integral to the Kosmos.

Fighting Manhood is Integral to the Moral Universe.

Which is Ordered by the Gods.

So :

Manliness -- Fighting Manliness -- is Godliness.

Ancient civilization -- both Greek and Roman -- understood and believed that.

Fervently.

Our "civilization" -- has forgotten it.

It needs to be UN-forgotten.

Now :

That great and overwhelming Warrior Wisdom, that Wisdom of a Godly Moral Order which is intrinsically Manly and intrinsically Warrior -- that's to say, a Moral Order based upon FIGHTING Manhood -- is core to who Plato is.

And what he believes.

For example --

In the Republic, Plato presents his own, per Paul Shorey, "distinctively Platonic sense of [the ancient Greek word] Thumos Θυμος" -- which means Spirit -- but which, in Plato's thinking, indicates "the power of noble wrath and righteous indignation," which is allied to Reason -- Manly Reason :

Sokrates:

Footnote from Paul Shorey:

[1] We now approach the distinctively Platonic sense of Thumos Θυμος as the power of noble wrath, which, unless perverted by a bad education, is naturally the ally of the reason, though as mere angry passion it might seem to belong to the irrational part of the soul, and so, as Glaucon suggests, be akin to appetite, with which it is associated in the mortal soul of the Timaeus 69 D. In Laws 731 B-C Plato tells us again that the soul cannot combat injustice without the capacity for righteous indignation.

For Plato, Thumos is, per Shorey, the power of noble wrath, the capacity for righteous indignation, without which the soul -- and the Man -- cannot combat injustice.

Which injustice is an inescapable aspect of the world of becoming.

And which injustice is, much of the time, per Lendon, hybris, an arrogant insult to Timé.

Which is Manhood.

Which means that Plato's concept of Thumos is another aspect of his essentially Warriordom and Warrior World of Being -- way of thinking.

Plato, like most ancient Greeks, thinks like a Warrior.

And, artist that he is, Plato uses the word Thumos in a variety of ways, of which one of the most striking is

Thumos gennaios : noble or high-minded passion.

Related:

Thumoeides : high-spirited, courageous (Plato), hot-tempered (Xenophon)

Related:

Thumuo : to make angry, to be angry

And guys, if you click on the link, you'll see that Thumos -- spirit, courage, anger -- is the root of Thumuo -- to be angry -- ; just as Ares is the root of Areté -- and Aristos.

Also related -- conceptually -- are

Phuché : breath, life, spirit, the soul or spirit of man ; and

Euphuchia : good courage, high spirit

The Soul and Spirit of Man, then, to the Greeks, is innately courageous and high-spirited.

And as we'll see -- a Spartan king uses euphuchia to refer -- to Spartan bravery.

Translation, and once again :

While the particular expression of these ideas belongs to Plato, the ideas are not his alone -- they are part of his Warriordom and his Warrior Kosmos, and so are found among Men -- Warriors -- who not only had no contact with Plato and his works, but who lived before he was born, or long after he'd died, and so forth.

Put differently, Plato often gives voice to a Warrior Ethos which was widespread among the Greeks and particularly prominent among the Spartans.

That said, let's get back to Plato's Principle of High Spirit, and the conversation between Sokrates and Glaukon, one of Plato's brothers :

Sokrates :

Glaukon :

"But," I said, "I once heard a story which I believe, that Leontius the son of Aglaion, on his way up from the Peiraeus under the outer side of the northern wall, becoming aware of dead bodies that lay at the place of public execution at the same time felt a desire to see them and a repugnance and aversion, and that for a time he resisted and veiled his head, but overpowered in despite of all by his desire, with wide staring eyes he rushed up to the corpses and cried, 'There, ye wretches, take your fill of the fine spectacle!' "

"I too," he said, "have heard the story."

"Yet, surely, this anecdote," I said, "signifies that the principle of anger sometimes fights against desires as an alien thing against an alien."

"Yes, it does," he said.

"And do we not," said I, "on many other occasions observe when his desires constrain a man contrary to his reason that he reviles himself and is angry with that within which masters him and that as it were in a faction of two parties the high spirit of such a man becomes the ally of his reason? But its making common cause with the desires against the reason when reason whispers low 'Thou must not' -- that, I think, is a kind of thing you would not affirm ever to have perceived in yourself, nor, I fancy, in anybody else either."

"No, by heaven," he said.

"Again, when a man thinks himself to be in the wrong, is it not true that the nobler he is the less is he capable of anger though suffering hunger and cold and whatsoever else at the hands of him whom he believes to be acting justly therein, and as I say his spirit refuses to be aroused against such a one?"

"True," he said.

"But what when a man believes himself to be wronged, does not his spirit in that case seethe and grow fierce (and also because of his suffering hunger, cold and the like) and make itself the ally of what he judges just [dikaios] ; and in noble [gennaios] souls it endures and wins the victory and will not let go until either it achieves its purpose, or death ends all, or, as a dog is called back by a shepherd, it is called back by the reason within and calmed."

"Your similitude is perfect," he said, "and it confirms our former statements that the helpers [epikouros -- assisters, allies επικουρος -- warriors] are as it were dogs subject to the rulers who are as it were the shepherds of the city."

"You apprehend my meaning excellently," said I. "But do you also take note of this? -- That what we now think about the spirited element is just the opposite of our recent surmise. For then we supposed it to be a part of the appetitive, but now, far from that, we say that, in the factions of the soul, it much rather marshals itself on the side of the reason."

"By all means," he said.

"Is it then distinct from this too, or is it a form of the rational, so that there are not three but two kinds in the soul, the rational [logistikos] and the appetitive, or just as in the city there were three existing kinds that composed its structure, the moneymakers, the helpers [warriors], the counsellors, so also in the soul there exists a third kind, this principle of high spirit [thumoeides], which is the helper of reason by nature unless it is corrupted by evil nurture?"

"We have to assume it as a third," he said.

"Yes," said I, "provided it shall have been shown to be something different from the rational, as it has been shown to be other than the appetitive."

"That is not hard to be shown," he said; "for that much one can see in children, that they are from their very birth chock-full of rage and high spirit, but as for reason, some of them, to my thinking, never participate in it, and the majority quite late."

~Plat. Rep. 4.439e, translated by Shorey.

So, and just for starters :

Plato's saying that the Principle of High Spirit, that is, the Spirit of Just Indignation -- of Anger at a Wrong -- is allied with Reason -- Manly Reason -- provided that it has been properly nurtured -- provided, I would say, that the proper Structure has been present for its nurturing -- as it was at Sparta.

And that this is the Spirit which enables a Man to Fight -- Injustice.

And given that to Plato, Fighting Manhood is Moral Manhood -- Pious, Temperate, and Morally-Ordered -- Thumos is virtually identical to -- Fighting Spirit.

Of which, by the way, Ares is Guardian.

And we can see that particularly well in the adjectival form of Thumos, Thumoeides, which means high-spirited, courageous.

In other words, imbued with Fighting Spirit.

Which is Fighting Manhood.

Of which Ares is God.

Just as the adjectival form of Euphuchia, which is Euphuchos, means high-spirited, courageous.

In other words, imbued with Fighting Spirit.

Which is Fighting Manhood.

Of which Ares is God.

So -- in the "city," the city-state, the Republic, there are three classes : the money-makers ; the Warriors -- for whom Plato here uses the wonderful word epikouros ; and the counsellors -- the wise men.

While in the individual soul, there's desire or appetite ; Fighting Spirit ; and Reason.

And, given the proper education, Fighting Spirit -- which is Manliness -- and Reason -- which is Manly -- are naturally allied -- they work together.

Plato thus sets out for us a Warrior Conception -- of Man's Inner Nature.

In which the Principle of High Spirit -- Fighting Spirit -- is one-third of the Man ;

and Manly Reason is the second third.

And Manly Reason and Fighting Spirit work together to govern the remaining third -- which is desire.

Which means that the two highest faculties of Man -- are his Manly Reason -- and his Fighting Spirit.

Further, that Fighting Spirit must be understood for what it is -- as an aspect of Lord Ares -- which is to say, a Divine Expression of the Warrior God, the God of High-Minded Passion and Noble Anger -- within the human soul.

Properly nurtured and welcomed, the God is within us.

And He's the God of High-Minded Passion and Noble Anger.

Which goes back to what we discussed in Chapter I -- the Gods, including Ares, are Good and Beneficent -- High-Minded and Noble.

And Noble, I remind you, means SELFLESS.

Unlike human beings, the Gods are not inherently selfish, nor are they controlled by their appetites.

Just the opposite.

By their very nature, the Gods are Selfless -- in part, because They need nothing.

Which is why what Sallustius says is True :

Which means that for a human being To Become Like to a God -- so far as may be -- entails becoming Selfless.

Which is why a male's attitude towards money matters.

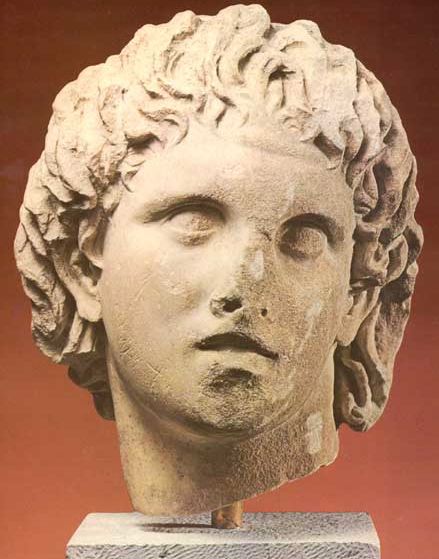

And why this one observation by Arrian--

tells us so much about Alexander the Great.

And about you.

Because, with just one exception, there's not a one of you to whom Arrian's words could even remotely be applied.

You're truly disgusting.

The only reason I put up with you is that the so-called gay community's continuing embrace of the act which killed my Lover disgusts me more.

But only by so much.

In all but that one department, you have nothing to recommend you.

Nothing.

So --

Ares, unlike you, but like all the Gods, is Selfless.

His Passion is High-Minded ; his Anger is Noble and thus Selfless.

I've tried explaining that to some of you and found that not only that you do not, but that you cannot, understand it.

How could you?

All you've known -- and want to know -- is selfishness.

That's all that interests you.

Sallustius says of the Gods, correctly -- it's what any religious teacher would say --

And how do you become fit?

Fitness is obtained by imitation, and imitation is the basis of all cult

And that's a problem.

Because you're not capable of imitation.

Imitation of the Gods would require that you become Selfless -- just for starters -- and you're not capable of that.

Which means that you'll spend your lives permanently divorced -- from the Divine.

Forever separated -- from the Sacred.

Sallustius :

You are for now, and for ever, separated from the Gods.

And I can't change that.

Only you can change it.

And you give no sign -- and have not for fifteen years -- of being able to change it -- or being even ever-so-slightly interested -- in changing it.

So -- it won't change.

Nevertheless, and to get back to the matter obstensibly at hand :

Ares, as the God of Fight and Fighting Manhood, is the God of High-Minded Passion and Noble Anger.

Which goes back to what we discussed in Chapter I -- the Gods, including Ares, are Good and Beneficent -- High-Minded and Noble.

Moreover :

In his footnote to Plato's introduction of Thumos, the Principle of High Spirit which is Fighting Spirit, Shorey refers us to Plato's Laws 731 B-C :

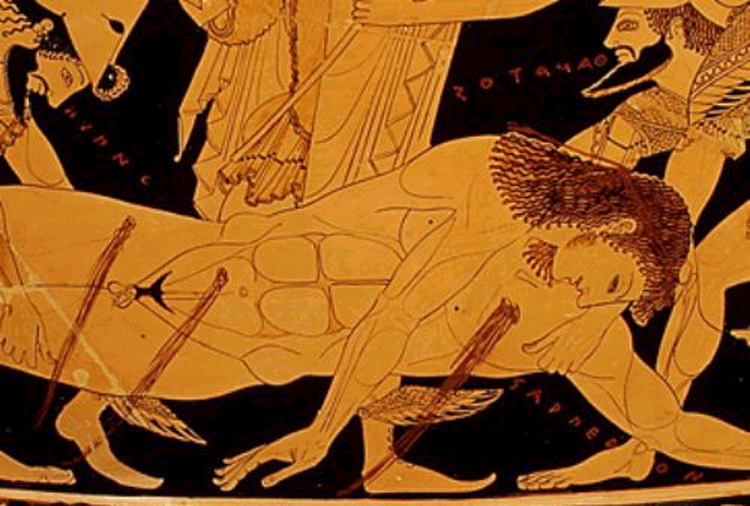

Every man ought to be at once passionate [thumoeides : high-spirited, courageous] and gentle in the highest degree. For, on the one hand, it is impossible to escape from other men's wrongdoings, when they are cruel and hard to remedy, or even wholly irremediable, otherwise than by victorious [nikao] fighting [machomai] and self-defence [amuno], and by punishing most rigorously ; and this no soul can achieve without noble passion [thumos gennaios].

So, in a very strong statement in the Laws, and one in which he clearly had Sparta in mind, Plato first urges that the citizens of a city-state -- and please remember that in a Greek city-state, the citizens were Men --

Plato first urges that the citizens of a city-state contend -- compete -- to attain the highest degree of Manliness and Manhood, but without jealousy and the slander which accompanies it.

Which is exactly and precisely what the Spartans did :

Charillus

When someone asked him what type of government he considered to be the best [aristos -- the most manly], he said, 'The one in which the largest number of citizens are willing to compete [agonizomai -- contend, fight, struggle] with each other in virtue [areté -- Fighting Manhood], and without civil discord.'

~ Plutarch, Sayings of the Spartans, 68.4, translated by Talbert.

That system was very effective.

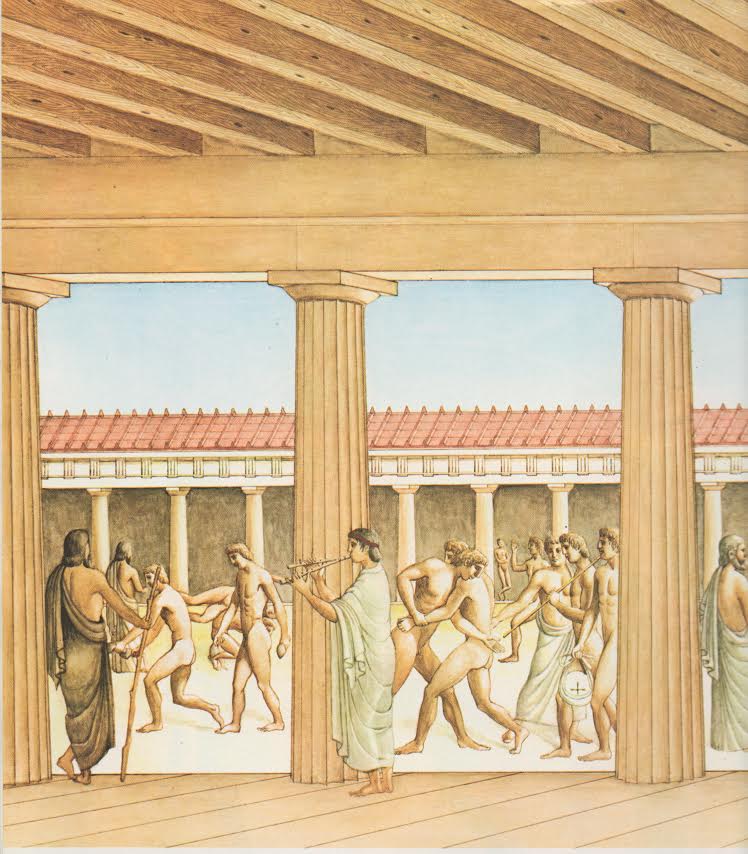

The "citizens," who at Sparta were the Warriors, were encouraged, from their earliest moments in the agogé, to compete in both aggression -- Manliness, Manhood, Fighting Spirit -- and obedience.

Lendon :

Sparta was supreme in Manhood -- Fighting Manhood.

The Spartan Homoioi [homoios ομοιος -- hoi homoioi = the equals] -- the Equals -- strove to create, through their uniquely Spartan institutions, which prized and rewarded both aggression and obedience aka harmony -- a Homonoia -- a Concord of Equals -- while year after year churning out the Manliest Warriors -- in Greece.

We can see those institutions and that Homonoia in action in this paragraph from Plutarch's Life of the Spartan king Agesilaus :

During the year that he spent in one of the companies [boua -- herds] of boys who were brought together under the Spartan system [the agogé], he had as his lover [the great Spartan general] Lysander, who was especially struck by his natural modesty and discretion [kosmios -- decorum, good order, moderation]. Agesilaus was more aggressive [philoneikos -- strife-loving] and hot-tempered [thumoeides -- courageous, full of fighting spirit] than his companions. He longed to be first in all things, and he had in him a vehemence [sphodros]

and impetuosity [actually, fury -- ragdaios] which were inexhaustible [and none would contend with], and carried him over all obstacles ; yet at the same time he was so gentle and ready to obey authority that he did whatever was demanded of him. He acted in this way from a sense of honour, not of fear, and he was far more sensitive to rebuke than to any amount of hardship [ponos]. He was lame in one leg, but the beauty of his physique in the prime of his youth made the deformity pass almost unnoticed, and the ease and light-heartedness with which he endured it went far to compensate for the disability, since he was the first to joke and make fun of himself on this subject. In fact his lameness served to reveal his ambition [PhiloTimia -- his Love of Worth] even more clearly, since he never allowed it to deter him from any enterprise, however arduous it might turn out. . . .

~Plut. Ages. 2.1-2, translated by Scott-Kilvert.

So : Agesilaus is aggressive -- philoneikos, he has a love of strife and contention -- and "hot-tempered" -- and the word is Plato's, thumoeides, courageous, full of fighting spirit ; as a consequence, Agesilaus longs to be first in all things -- just as Plato says he should -- with a vehemence and impetuosity -- the latter word in Greek is actually "fury" -- and in Chapter V we'll discuss the Latin word furor -- a hallmark of the young Warrior -- which are inexhaustible and which none want to contend with, and which, as a consequence, carry him over all obstacles ;

while, at the same time, Agesilaus is ready to obey authority and do whatever is demanded of him, not out of fear, but from a sense of honour ;

and he's far more sensitive to rebuke than to any amount of hardship.

In other words, Agesilaus advances in Manly Excellence, in Fighting Manhood, not through calumny, not through slandering his fellow boys, but through a combination of Aggression -- Fighting Spirit -- Plato's thumos -- and Obedience -- which is really an expression of Harmony with both his fellows in the agogé and the Spartan "system" -- Ta Kala -- The Noble Way -- in general.

So :

Manhood -- Fighting Manhood -- is the goal ; and it's best achieved in a society which values and creates order, harmony, discipline, and restraint.

And notice, in Plutarch's account of Agesilaus, the many words we see which we frequently encounter in discussions of Greek Warrior Culture -- and in Plato :

Greek Warrior Culture, and particularly Spartan Warrior Culture, is consistent -- it wants its Youth and Men to be strife-loving and contentious, courageous and full of fighting spirit ; to never shirk from toil, physical labor, or the hardship of battle --

While pursuing Worth and Honor within a system which encourages decorum, modesty, good order, restraint, discipline, and harmony.

That's why the Spartan king, Charillus, says, The best State is 'The one in which the largest number of Warriors are willing to compete, contend, fight, and struggle with each other in Fighting Manhood -- and without civil discord -- without disrupting the Good Order and Good Harmony of the State.'

And that in turn is why, in the Laws, albeit four centuries later, Plato says,

And, Plato then says, no doubt thinking of his beloved Dion, that every man should be both passionate [thumoeides : high-spirited, courageous] and gentle in the highest degree ; and,

That Thumos gennaios -- high-minded passion, noble anger -- which again, is an expression of Fighting Spirit -- is what enables and indeed is necessary for a Man to escape from other males' wrongdoing -- through victorious Fighting and Self-Defense -- which includes rigorous punishment of the wrong-doer.

Again, this is a strong statement by a strong Man and a Warrior, and one with an eye on the Homeric past, calling upon Men to strive -- essentially, to compete, but without jealousy or rancour -- for Manhood -- Morally Just Fighting Manhood -- and saying that you can't, in this chaotic world of becoming, escape the wrongdoing of others -- other than through Victorious Fighting and Self-Defense -- and by rigorous punishment of malefactors -- and that no soul can achieve this without high-minded passion, noble anger, righteous indignation, fighting spirit.

And remember, please, that Thumos means spirit, and that Thumos gennaios -- that noble anger which leads to noble deeds -- is a SPIRITUAL quality.

That's what it is.

It's spiritual.

So that in terms of Unitary Virtue, it can be thought of as Hallowed Fighting Manhood in the service of Restraint, Discipline, and Manly Moral Order.

Thumos gennaios -- noble anger, righteous indignation -- is a spiritual quality, a quality of the Warrior's Soul, originating of necessity in the Warrior World of Being, the Warrior Kosmos, and mediated by Lord Ares so as to enable the Warrior's actions in the world of becoming.

Sallustius :

The God -- in this case, Ares -- exists to help the human being -- in this case the Warrior -- to overcome the chaos of embodiment in the world of becoming.

How?

In part, through imitation :

. . .

These considerations decide the problem of worship. The Gods need nothing ; the honours we pay them are for our own benefit. Their providence extends everywhere, and all who are fit may enjoy it.

Fitness is obtained by imitation.

Which is why Plato says homoiosis Theo -- to be like to God -- or to a God.

And when Plato says "homoiosis Theo," he's talking about, in part, Thumos gennaios -- a very Militant and Manly Warrior Righteousness :

It's here that the superficiality of a male -- his worthlessness, his nothingness, his complete want of Manhood -- is found ; for the Knowledge of Righteousness, of Manly Moral Order, is Wisdom -- that is, True Manhood ; and ignorance of it is willful blindness and manifest and excremental wickedness ; and all the other kinds of seeming cleverness and wisdom are paltry when they appear in public affairs and vulgar in the arts.

And then we come back to Plato's statement in the Laws :

Every man ought to be at once passionate [thumoeides : high-spirited, courageous] and gentle in the highest degree. For, on the one hand, it is impossible to escape from other males' wrongdoings, when they are cruel and hard to remedy, or even wholly irremediable, otherwise than by victorious [nikao] fighting [machomai] and self-defence [amuno], and by punishing most rigorously ; and this no soul can achieve without noble passion [thumos gennaios].

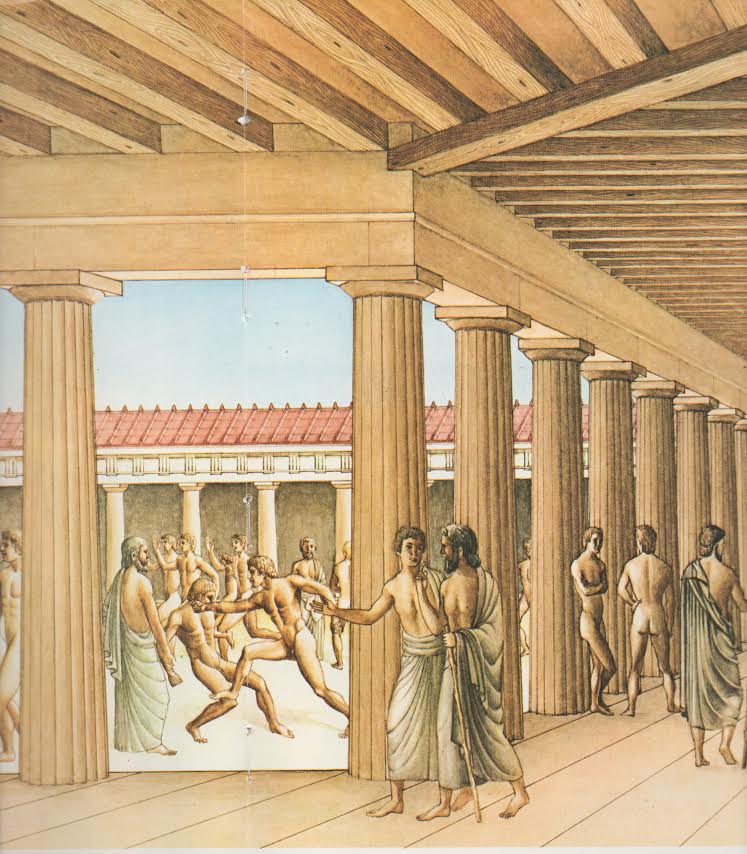

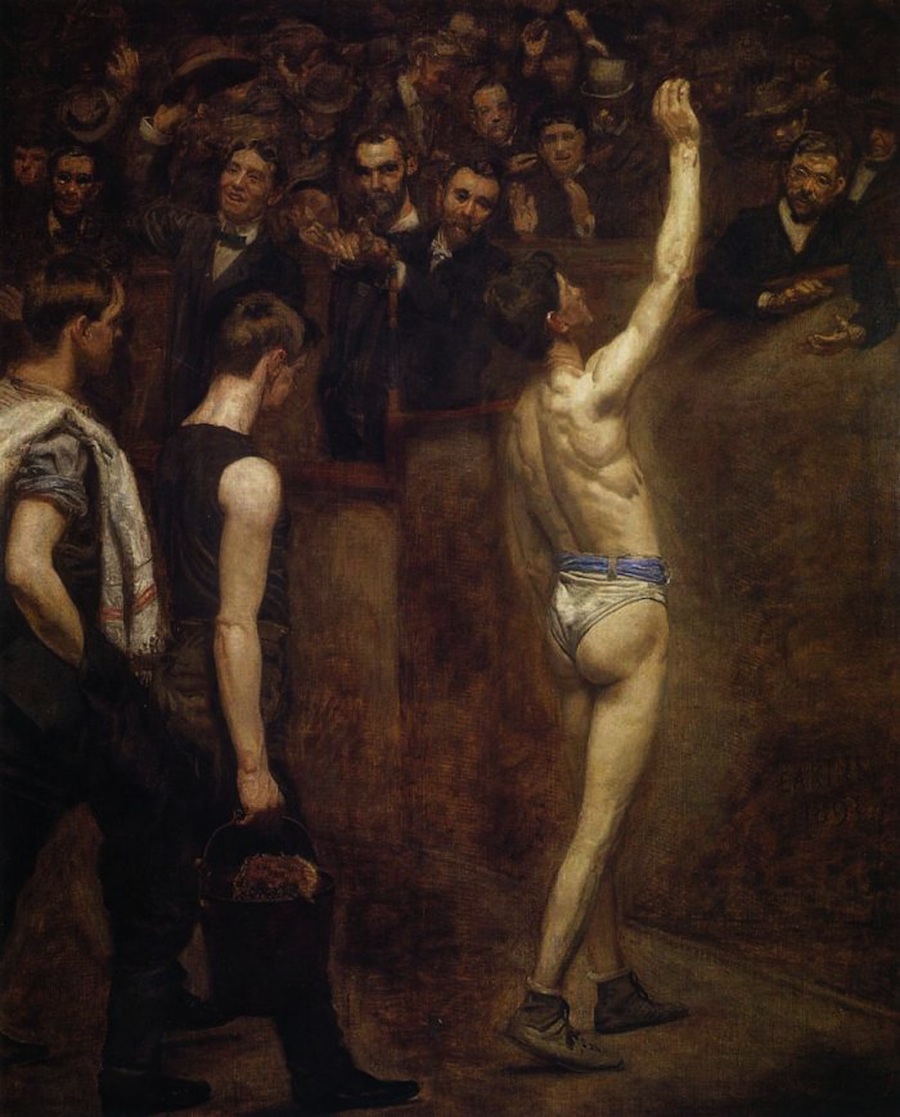

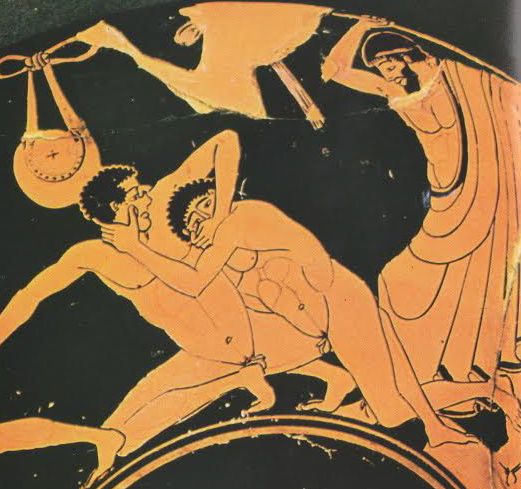

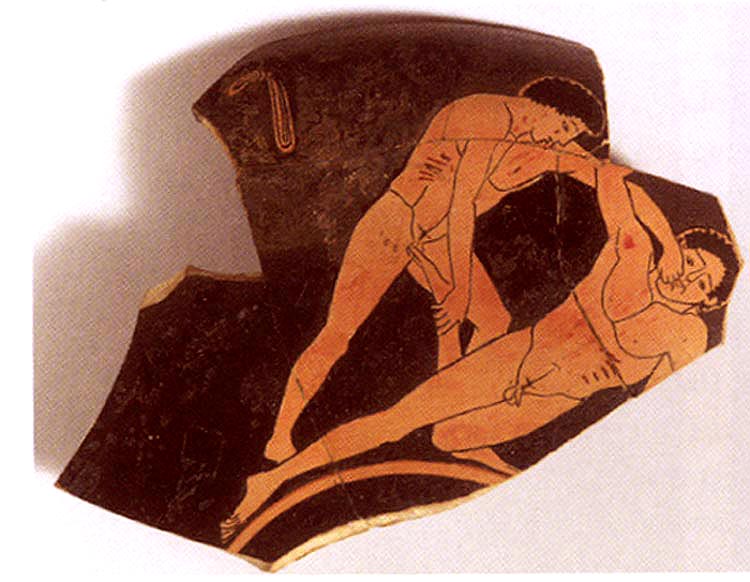

And having read that statement by Plato in the Laws, we can better understand his earlier statement in the Republic, that the Guardians of his ideal city -- his Republic -- will settle their personal disputes -- through fist-fights.

So :

In Book V of the Republic, Plato is discussing how the "Guardians" -- the Warrior Caste of his ideal city-state -- and ideal Men -- will possess nothing, not even wives or children -- and that this will keep them free of dissensions and disputes :

"They will necessarily be quit of these," he said.

"And again, there could not rightly arise among them any law-suit for

assault or bodily injury. For as between age-fellows [men of the same

age, comrades] we shall say that self-defence [to defend oneself, to

repel an assault] is honorable [kalon -- morally beautiful] and just [dikaios]

"And again, there could not rightly arise among them any law-suit for

assault or bodily injury. For as between age-fellows [men of the same

age, comrades] we shall say that self-defence [to defend oneself, to

repel an assault] is morally beautiful [kalon] and just, well-ordered, and righteous [dikaios], thereby

compelling them to keep their bodies in condition."

"Right," he said.

"And there will be the further advantage in such a law that an

angry man, satisfying his anger in such wise, would be less likely to

carry the quarrel to further extremes."

"Assuredly."

"As for an older man, he will always have the charge of ruling and

chastising the younger."

~Plat. Rep. 5.464e, translated by Shorey

Let's play that again.

Plato, the greatest thinker of his age, and many believe, any age, is saying that among the Warriors in his ideal state,

And you'll notice that the translator, Paul Shorey, has a footnote after the word for age-mate/comrade -- which reads as follows :

So, Shorey refers us back to Xenophon's account of the Strife of Valour, the Struggle of, for, and about Manhood, in "Rep. Lac. 4.5" [ = Lakedaimonian Republic 4.5] :

Here then you find that kind of strife that is dearest to the Gods, and in the highest sense political -- the strife that sets the standard of a brave man's conduct ; and in which either party exerts itself to the end that it may never fall below its best, and that, when the time comes, every member of it may support the state with all his might.

And they are bound, too, to keep themselves fit, for one effect of the strife is that they fight whenever they meet ; but anyone present has a right to part the combatants.

So -- what both Plato and Xenophon are saying -- and it's truly eye-opening for Men like ourselves, living in the times we do --

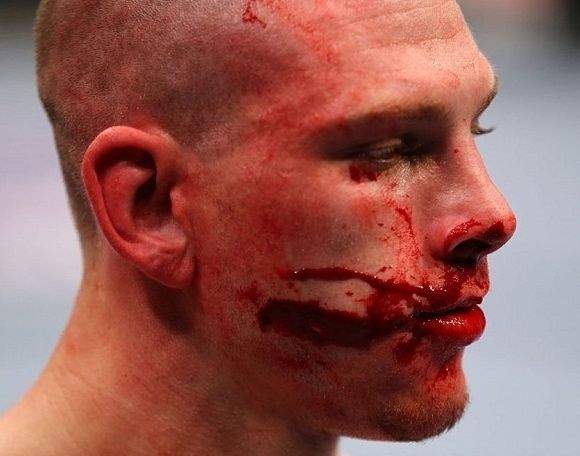

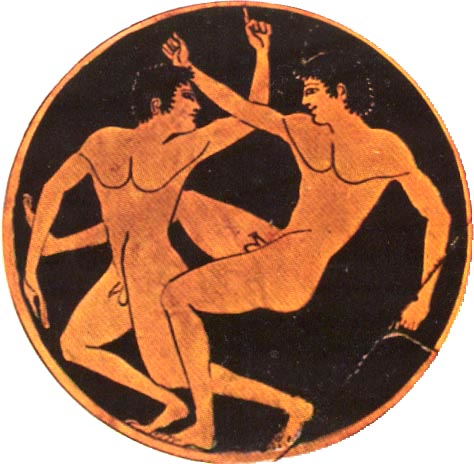

is that Fist Fights -- and these are Fist Fights -- in Laws 880 A, which Shorey also refers us to, Plato says explicitly that "the man attacked shall defend himself with bare hands, as nature dictates, and without a weapon" ;